A Guide to White-Nose Syndrome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nine Species of Bats, Each Relying on Specific Summer and Winter Habitats

Species Guide to Vermont Bats • Vermont has nine species of bats, each relying on specific summer and winter habitats. • Six species hibernate in caves and mines during the winter (cave bats). • During the summer, two species primarily roost in structures (house bats), • And four roost in trees and rocky outcrops (forest bats). • Three species migrate south to warmer climates for the winter and roost in trees during the summer (migratory bats). • This guide is designed to help familiarize you with the physical characteristics of each species. • Bats should only be handled by trained professionals with gloves. • For more information, contact a bat biologist at the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department or go to www.vtfishandwildlife.com Vermont’s Nine Species of Bats Cave Bats Migratory Tree Bats Eastern small-footed bat Silver-haired bat State Threatened Big brown bat Northern long-eared bat Indiana bat Federally Threatened State Endangered J Chenger Federally and State J Kiser Endangered J Kiser Hoary bat Little brown bat Tri-colored bat Eastern red bat State State Endangered Endangered Bat Anatomy Dr. J. Scott Altenbach http://jhupressblog.com House Bats Big brown bat Little brown bat These are the two bat species that are most commonly found in Vermont buildings. The little brown bat is state endangered, so care must be used to safely exclude unwanted bats from buildings. Follow the best management practices found at www.vtfishandwildlife.com/wildlife_bats.cfm House Bats Big brown bat, Eptesicus fuscus Big thick muzzle Weight 13-25 g Total Length (with Tail) 106 – 127 mm Long silky Wingspan 32 – 35 cm fur Forearm 45 – 48 mm Description • Long, glossy brown fur • Belly paler than back • Black wings • Big thick muzzle • Keeled calcar Similar Species Little brown bat is much Commonly found in houses smaller & lacks keeled calcar. -

Owls and Bats That Live in Indiana As Well As Introduce You to Characteristics of Owls and Bats and Their Basic Lifestyles

Owls & Bats Pre-Visit Packet The activities in this pre-visit packet have been designed to help you and your students prepare for your upcoming What Goes “Bump” in the Night? program at the St. Joseph County Parks. The information in this packet will help your students become more familiar with the owls and bats that live in Indiana as well as introduce you to characteristics of owls and bats and their basic lifestyles. Of course, if you do not have time to do the activities prior to your park visit, they will also work as a review for what the students learned during the program. Test Your Bat IQ Discuss the following questions and answers as a group: 1. What kind of animals are bats: birds, reptiles, mammals or amphibians? Answer: Bats are mammals. They are warm-blodded, have fur, give birth to live young and feed their babies milk. 2. What is the wingspan of the biggest bat in the world: 1 foot, 6 feet or 50 feet? Answer: The world’s biggest bat is called a Flying Fox. It lives in Java (in Asia) and has a wingspan of about 6 feet. 3. The smallest bat in the world is the size of what animal: a guinea pig, an ant or a bumblebee? Answer: The smallest bat in the world is the Bumblebee Bat, which lives in Thailand. It is about the size of a bumblebee! 4. Which of the following foods are eaten by bats: insects, fish, blood, nectar or fruit? (Hint: There is more than one correct answer.) Answer: Bats eat all of the foods listed! However, all of the bats that live in Indiana are insect-eaters. -

Bat Damage Ecology & Management

LIVING WITH WILDLIFE IN WISCONSIN: SOLVING NUISANCE, DAMAGE, HEALTH & SAFETY PROBLEMS – G3997-012 Bat Damage Ecology & Management As the world’s only true flying mammal, bats have extremely interesting lifestyles. They belong to the order Chiroptera, S W F S U – which means “hand wing.” There are s t a b n w ro approximately 1,400 species of bats world- b le tt li g in at wide, with 47 species residing in the United n er ib States. Wisconsin was home to nine bat species H at one time (there was one record of the Indiana bat, Myotis sodalis, in Wisconsin), but only eight species are currently found in the state. Our Wisconsin bats are a diverse group of animals that are integral to Wisconsin’s well-being. They are vital contributors to the welfare of Wisconsin’s economy, citizens, and ecosystems. Unfortunately, some bat species may also be in grave danger of extinction in the near future. DESCRIPTION “Wisconsin was home to nine bat species at one time, but All Wisconsin’s bats have only eight species are currently found in the state. egg-shaped, furry bodies, ” large ears to aid in echolo- cation, fragile, leathery wings, and small, short legs and feet. Our bats are insectivores and are the primary predator of night-flying insects such as mosquitoes, beetles, moths, and June bugs. Wisconsin’s bats are classified The flap of skin as either cave- or tree- connecting a bat’s legs is called the dwelling; cave-dwelling bats uropatagium. This hibernate underground in structure can be used as an “insect caves and mines over winter net” while a bat is feeding in flight. -

(RVS) Raccoon, Fox, Skunk

Most Common Bats in So MD Little Brown Bat, Evening Bat, Red Bat, Big Brown Bat Little Brown Bat 4 – 9 g body weight 3 1/8 – 3 7/8” length 9 - 11” wing span 10 – 30 year lifespan Single bat catches up to 600 mosquitoes per hour Long, glossy dark fur, long hairs on hind feet extend beyond tips of claws. Face, ears, and wing membranes are dark brown Mate late August – November, sperm stored until spring, one pup born May or June after 60 day gestation Pup weighs up to 30% of mother’s weight which is like a 120 lb woman giving birth to a 36 lb baby Pups hang onto mom for 3 – 4 days, even during feeding. Pups capable of flight at 18 days and adult size at 3 weeks Evening Bat 6 - 13 g body weight 3 – 3 7/8” length 10 - 11” wing span 2 – 5 year lifespan Colony of 300 Evening Bats will consume 6.3 million insects per summer Fur is short, dull brown, belly paler. Ears/wing membranes blackish brown Average of 2 pups born late May or early June. Born pink and hairless with eyes closed. Capable of flight within 20 days and nearly adult sized at 4 weeks. Weaned at 6 – 9 weeks Red Bat 9 - 15 g body weight 3.75 - 5” length 11 - 13” wing span 32 teeth/40mph flight Bright orange to brick red angora-like fur often with frosted appearance (females more frosted than males), white shoulder patches. Heavily furred tail membrane. Females have 4 nipples unlike most bats with 2 Mating season Aug – Sept, sperm stored until following spring (April-May). -

Little Brown Myotis Myotis Lucifugus

Wyoming Species Account Little Brown Myotis Myotis lucifugus REGULATORY STATUS USFWS: Petitioned for Listing USFS R2: No special status UWFS R4: No special status Wyoming BLM: No special status State of Wyoming: Nongame Wildlife CONSERVATION RANKS USFWS: No special status WGFD: NSS3 (Bb), Tier II WYNDD: G3, S5 Wyoming Contribution: LOW IUCN: Least Concern STATUS AND RANK COMMENTS In 2011, a status review was submitted to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) suggesting that Little Brown Myotis (Myotis lucifugus) be listed as Endangered on an emergency basis because of massive population declines in the northeastern U.S. from White-nose Syndrome (WNS) 1. As of 2016, the USFWS had not yet completed this assessment or issued any decision on whether Threatened or Endangered status was warranted. NATURAL HISTORY Taxonomy: There are five recognized subspecies of Little Brown Myotis: M. l. alascensis, M. l. carissima, M. l. lucifugus, M. l. pernox, and M. l. relictus 2, 3. In Wyoming, M. l. carissima is the only known subspecies3. These sub-specific designations have been questioned as recently as 2008 because of the overlapping ranges of subspecies and evidence of subspecies-level hybridization from mitochondrial and nuclear DNA analyses 4. Description: Little Brown Myotis is, with few exceptions, identifiable in the field 5. The species is a small vespertilionid bat, but medium in size among Myotis species 5. Pelage is variable in color. Generally, the dorsal side is glossy and sooty brown to pale golden brown, while the ventral side is a lighter yellow or olive brown 3, 5, 6. In early summer, juveniles can be distinguished from adults by noticeably darker pelage and lower mass 3. -

Little Brown Bat, Myotis Lucifugus, EC 1584

EC 1584 • September 2006 $1.00 Little Brown Bat Myotis lucifugus by L. Schumacher and N. Allen ittle brown bats are one of the most common bats in Oregon and L the United States. Their scientifi c name is Myotis lucifugus. The group of bats in the genus Myotis are called the “mouse-eared” bats. Where they live Little brown bats’ favorite foods are and why gnats, beetles, and moths. They also eat Bats need food, water, and shelter. lots of mosquitoes. They help humans by Little brown bats live almost everywhere eating mosquitoes that bite us and beetles in the United States except in very dry that eat our crops. They are important to areas, such as deserts. the ecosystem too. Without bats, there Bats often hunt at night about 10 feet would be too many insects. above the water, where they can fi nd lots Bats are gentle animals. They do not of insects. Bats also need water to drink. attack humans. There is no reason to be They fl y across the surface and swallow scared of a bat. But remember, bats are water as they fl y. wild animals. Never try to touch a bat. If During the day, little brown bats roost, you fi nd a sick or hurt bat, be sure to tell or rest. Bats live only where they have an adult right away. safe places to rest during the day. Hollow trees and tree cavities made by wood- peckers are popular roosts. During the early summer, many moth- ers and their babies live together in giant nursery roosts, which are places that always stay warm and dry. -

Status Report and Assessment of Big Brown Bat, Little Brown Myotis

SPECIES STATUS REPORT Big Brown Bat, Little Brown Myotis, Northern Myotis, Long-eared Myotis, and Long-legged Myotis (Eptesicus fuscus, Myotis lucifugus, Myotis septentrionalis, Myotis evotis, and Myotis volans) Dlé ne ( ) Daatsadh natandi ( wic y wic i ) Daat i i (T i wic i ) T ( wy ) ( c ) Sérotine brune, vespertilion brun, vespertilion nordique, vespertilion à longues oreilles, vespertilion à longues pattes (French) April 2017 DATA DEFICIENT – Big brown bat SPECIAL CONCERN – Little brown myotis SPECIAL CONCERN – Northern myotis DATA DEFICIENT – Long-eared myotis DATA DEFICIENT – Long-legged myotis Status of Big Brown Bat, Little Brown Myotis, Northern Myotis, Long-eared Myotis, and Long-legged Myotis in the NWT Species at Risk Committee status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of species suspected of being at risk in the Northwest Territories (NWT). Suggested citation: Species at Risk Committee. 2017. Species Status Report for Big Brown Bat, Little Brown Myotis, Northern Myotis, Long-eared Myotis, and Long-legged Myotis (Eptesicus fuscus, Myotis lucifugus, Myotis septentrionalis, Myotis evotis, and Myotis volans) in the Northwest Territories. Species at Risk Committee, Yellowknife, NT. © Government of the Northwest Territories on behalf of the Species at Risk Committee ISBN: 978-0-7708-0248-6 Production note: The drafts of this report were prepared by Jesika Reimer and Tracey Gotthardt under contract with the Government of the Northwest Territories, and edited by Claire Singer. For additional copies contact: Species at Risk Secretariat c/o SC6, Department of Environment and Natural Resources P.O. Box 1320 Yellowknife, NT X1A 2L9 Tel.: (855) 783-4301 (toll free) Fax.: (867) 873-0293 E-mail: [email protected] www.nwtspeciesatrisk.ca ABOUT THE SPECIES AT RISK COMMITTEE The Species at Risk Committee was established under the Species at Risk (NWT) Act. -

Facts About Washington's Bats

Bats Bats are highly beneficial to people, and the advantages of having them around far outweigh any problems you might have with them. As predators of night-flying insects (including mosqui toes!), bats play a role in preserving the natural balance of your property or neighborhood. Although swallows and other bird species consume large numbers of flying insects, they generally feed only in daylight. When night falls, bats take over: a nursing female little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus) may consume her body weight in insects each night during the summer. Contrary to some widely held views, bats are not blind and do not become entangled in peoples’ hair. If a flying bat comes close to your head, it’s probably because it is hunting insects that have been attracted Figure 1. Big brown bat by your body heat. Less than one bat in 20,000 has rabies, and no (Photo by Ty Smedes) Washington bats feed on blood. More than 15 species of bats live in Washington, from the common little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus) to the rare Townsend’s big-eared bat (Corynorhinus townsendii). Head to tail, bats range in length from the 2.5-inch-long canyon bat (Parastrellus hesperus), to the 6-inch long hoary bat (Lasiurus cinereus). The hoary bat has a body approximately the size of a house sparrow and a wingspan of 17 inches. The species most often seen flying around human habitat include the little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus), Yuma myotis (Myotis yumanen sis), big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus, Fig. 1), pallid bat (Antrozous pallidus), and California myotis (Myotis californicus). -

U.S. Geological Survey Response to White-Nose Syndrome in Bats

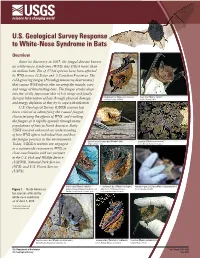

U.S. Geological Survey Response to White-Nose Syndrome in Bats Overview Since its discovery in 2007, the fungal disease known as white-nose syndrome (WNS) has killed more than six million bats. Ten of 47 bat species have been affected by WNS across 32 States and 5 Canadian Provinces. The cold-growing fungus (Pseudogymnoascus destructans) that causes WNS infects skin covering the muzzle, ears, and wings of hibernating bats. The fungus erodes deep into the vitally important skin of bat wings and fatally Big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus) Cave bat (Myotis velifer) disrupts hibernation of bats through physical damage Ann Froschauer, USFWS Public Domain, NPS and energy depletion as they try to cope with infection. U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) science has been critical in identifying the causal fungus, characterizing the effects of WNS, and tracking the fungus as it rapidly spreads through many populations of bats in North America. Early USGS research enhanced our understanding of how WNS affects individual bats and how the fungus persists in the environment. Eastern small-footed bat (Myotis leibii ) Gray bat (Myotis grisescens)1 Today, USGS scientists are engaged Virginia State Parks Larisa Bishop-Boros, CC license in a nationwide response to WNS, in close coordination with our partners at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), National Park Service (NPS), and U.S. Forest Service (USFS). Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis)1 Little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus) Northern long-eared bat (Myotis septentrionalis)2 Figure 1. North American Andrew Kniowski, Department of Fish and Alan Hicks, NY Department of Pete Patavino, USFWS Wildlife Conservation, Virginia Tech Environmental Conservation bat species affected by white-nose syndrome https://github.com/USGS-R/BatTool as of June 1, 2018. -

Petition to List the Tricolored Bat Perimyotis Subflavus As Threatened Or Endangered Under the Endangered Species Act

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR Photo Credit: Karen Powers PETITION TO LIST THE TRICOLORED BAT PERIMYOTIS SUBFLAVUS AS THREATENED OR ENDANGERED UNDER THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT June 14, 2016 CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY & DEFENDERS OF WILDLIFE NOTICE OF PETITION June 14, 2016 Sally Jewell Secretary of the Interior 18th and C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 Dan Ashe, Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Douglas Krofta, Chief Branch of Listing, Endangered Species Program U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 4401 North Fairfax Drive, Room 420 Arlington, VA 22203 [email protected] Dear Secretary Jewell: Pursuant to Section 4(b) of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. §1533(b), Section 553(3) of the Administrative Procedures Act, 5 U.S.C. § 553(e), and 50 C.F.R. §424.14(a), the Center for Biological Diversity and Defenders of Wildlife hereby formally petition the Secretary of the Interior to list the tricolored bat, Perimyotis subflavus, as a Threatened or Endangered species and to designate critical habitat concurrent with listing. This petition sets in motion a specific process, placing definite response requirements on the Secretary and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) by delegation. Specifically, USFWS must issue an initial finding as to whether the petition “presents substantial scientific or commercial information indicating that the petitioned action may be warranted.” 16 U.S.C. §1533(b)(3)(A). USFWS must make this initial finding “[t]o the maximum extent practicable, within 90 days after receiving the petition.” Id. -

White-Nose Syndrome Frequently Asked Questions Oregon and Washington

White-Nose Syndrome Frequently Asked Questions Oregon and Washington What is white-nose syndrome? White-nose syndrome (WNS) of bats is a disease caused by the fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans (Pd; formerly known as Geomyces destructans). The disease is estimated to have killed over six million bats in the eastern United States and Canada since 2006, and can kill up to 100% of bats in a colony during hibernation. This fungus thrives in cold and humid microclimates found in caves and abandoned mines. Several species of bats require these same cold and humid microclimates for hibernation. The disease received its name because infected bats are often observed with “white fuzz” around their nose and muzzle, and also on their wings, ears, or tail. The external white fungus may not always be visible, and is often absent when bats are found outside their roosts or hibernating sites. The fungus invades deep skin tissues and causes extensive damage. Infection by WNS causes the bats to arouse from hibernation during winter, which utilizes their very limited fat reserves and can ultimately lead to starvation and dehydration before spring, when their insect prey are available. Bats with WNS may exhibit a white fungus growing on their muzzles, ears, or wings while in their hibernacula (roosts where they hibernate) during winter months. Abnormal occurrences of bats near cliffs, rocks or the entrances to caves or mines during winter, exiting and flying around in the daytime during cold winter weather, and dead or lethargic bats on the ground are behaviors associated with WNS. Is white-nose syndrome here in the Pacific Northwest? Unfortunately, yes. -

What You Should Know About Bats

What You Should Know About Bats New Jersey is home to nine species of bats. Six species are year round residents and three species are migratory. Two species - the big brown bat and little brown bat - are often found roosting in colonies inside buildings. Other bats, called solitary bats, usually do not enter buildings. BAT FACTS # Bats are actually quite harmless and are an important part of the ecological balance. They play an active role in the control of nuisance insects. A single little brown bat can consume up to 1,200 mosquito sized insects in an hour and up to 3,000 insects in a single night. # Contrary to popular belief, less than one percent of bats carry rabies and attacks by bats are extremely rare. # Bats usually return to the same roost year after year and start maternity colonies in the spring. The young are born in June and July. Colonies can be present at the same location for over 100 years. Bats hibernate over winter. HOW DO YOU GET RID OF BATS YOUR HOME? The only permanent method to get rid of bats from a home and keep them out is to exclude them by bat-proofing. There are no chemicals registered in New Jersey for killing bats. Use of unregistered pesticides only increases the chances that children or pets will come into contact with sick bats. Bats often roost in dark, undisturbed areas like attics and wall spaces. The entry points are often near the roof edge - under the eaves, soffits or loose boards, openings in the roof or vents, or crevices around the chimney.