Managing Mass Tourism in Florence 2016-187.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fondazione Ifel

FONDAZIONE IFEL Rassegna Stampa del 10/04/2014 La proprietà intellettuale degli articoli è delle fonti (quotidiani o altro) specificate all'inizio degli stessi; ogni riproduzione totale o parziale del loro contenuto per fini che esulano da un utilizzo di Rassegna Stampa è compiuta sotto la responsabilità di chi la esegue; MIMESI s.r.l. declina ogni responsabilità derivante da un uso improprio dello strumento o comunque non conforme a quanto specificato nei contratti di adesione al servizio. INDICE IFEL - ANCI 10/04/2014 Il Sole 24 Ore 9 La trincea di medici e manager delle Asl 10/04/2014 La Repubblica - Firenze 10 Multe e tasse non pagate la task force comunale ancora non è pronta 10/04/2014 La Repubblica - Firenze 12 Fisco "rigoroso ma umano" per 2 milioni di toscani 10/04/2014 Il Gazzettino - Rovigo 14 «Il personale non ha alcun privilegio» 10/04/2014 Il Gazzettino - Udine 15 Anci e Università, scommessa tecnologica 10/04/2014 Libero - Nazionale 16 L'Anci e Nardella a bocca asciutta se la prendono con la Corte dei Conti 10/04/2014 Il Foglio 18 Come Renzi e Padoan governano le tradizionali tensioni Tesoro-Chigi 10/04/2014 ItaliaOggi 20 Ticket, linea dura 10/04/2014 ItaliaOggi 21 Autodisciplina pubblicitaria, 941 casi risolti nel 2013 10/04/2014 Giornale di Brescia 22 Strisce blu, multe discutibili per fare cassa 10/04/2014 Il Giornale del Piemonte 23 «Ufficio bandi per arrivare al 2030» 10/04/2014 La Prealpina - Nazionale 25 Bilanci virtuosi, Varese non brilla 10/04/2014 Messaggero Veneto - Nazionale 26 Comuni in rete per offrire più -

Cities Call for a More Sustainable and Equitable European Future

Cities call for a more sustainable and equitable European future An open letter to the European Council and its Member States Tuesday 30th April 2019, President of the European Council, Heads of States and Governments of the European Union Member States, We, the undersigned mayors and heads of local governments have come together to urge the Heads of States and Governments of the Member States to commit the European Union (EU) and all European institutions to a long-term climate strategy with the objective of reaching net-zero emissions by 2050 – when they meet at the Future of Europe conference in Sibiu, Romania on 9 May, 2019. The urgency of the climate crisis requires immediate action, stepping up our climate ambition and pursuing every effort to keep global temperature rise below 1.5C by mid-century, as evidenced by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5C. Current energy and climate policies in place globally, set the planet on a global warming pathway of 3°C. We are reminded of the inadequacy of our response to climate change, by the thousands of young people demonstrating each week on the streets of European cities - and around the world. We cannot let the status quo jeopardise their future and those of millions of European citizens. We owe it to the next generation to make more ambitious commitments to address climate change at all levels of government and in every aspect of European policy-making. We acknowledge and support the positions of the European Parliament and of the Commission to pursue net-zero emissions as the only viable option for the future of Europe and the world. -

Italy 2017 International Religious Freedom Report

ITALY 2017 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution protects freedom of religion and the right of religious communities to establish their own institutions. The constitution specifies the state and the Catholic Church are independent, their relations governed by treaties, which include a concordat granting the Church a number of privileges and benefits, as well as financial support. Other religious groups must register to receive tax and other benefits. Registered groups may request an accord with the state that provides most of the same benefits granted the Catholic Church. Muslims continued to report difficulties in acquiring permission from local governments to construct mosques or keep them open. In February the Ministry of Interior (MOI) signed an agreement with the country’s largest Muslim organization with the stated purpose of preventing radicalization and promoting the training of imams to manage funds transparently and deliver sermons in Italian. Following the ruling, Milan municipal officials continued to withhold authorization to build two new mosques and a Protestant church, citing limited capability to identify proper venues as required by the law. Local governments closed Bangladeshi informal “garage” mosques in Mestre and in Rome, and a group sought a referendum to block a new mosque in Pisa. In separate rulings, a Lazio court ordered authorities to reopen the five garage mosques that Rome officials had closed down in 2016. There were anti-Semitic and anti-Muslim incidents, including threats, hate speech, graffiti, and vandalism. In 2016, the most recent year for which data were available, the quasi-governmental National Office against Racial Discrimination (UNAR) reported 240 cases of discrimination based on religion, compared with 28 the previous year. -

Modern Slavery and Climate Change

SCIE IA NT EM IA D R A V C M A S O A I C C I I A F I L T I V N M O P MODERN SLAVERY AND CLIMATE CHANGE: THE COMMITMENT OF THE CITIES 21 JULY 2015 NEW SYNOD HALL VATICAN CITY Modern Slavery and Climate Change: The Commitment of the Cities #MayorsCare Esclavitud moderna y cambio climático: el compromiso de las ciudades Introducción oy día afrontamos dos urgencias dramáticas que, en cierto modo, están relacionadas: la crisis del cambio climático y las nuevas formas de esclavitud. Como dice Laudato si’, las consecuencias del cambio climático Hazotan con mayor fuerza a las personas más vulnerables del planeta, mientras que ellas ni siquiera disfrutan de las ventajas de usar los combustibles fósiles. Los líderes religiosos, llamados a condenar las nuevas formas de esclavitud, han subrayado la relación entre el ambiente natural y el ambiente humano. De hecho, el calentamiento global es una de las causas de la pobreza y de las migraciones forzadas, favoreciendo la trata de personas, el trabajo forzado, la prostitución y el tráfico de órganos. Más de 30 millones de personas son víctimas de la esclavitud moderna, traficadas en un mercado abominable con ganancias ilegales que se estiman en 150 000 millones de dólares al año. Desde el inicio de su pontificado, el Papa Francisco ha adoptado una postura firme contra la esclavitud moderna, exhortando a todas las comunidades a rechazar rotundamente y sin excepciones toda privación sistemática de la libertad individual con fines de explotación personal y comercial. Una de sus iniciativas, el Grupo Santa Marta, que fundó junto con el Cardenal Vincent Nichols, reúne a obispos y a organismos policiales de todo el mundo. -

Page 01 March 05.Indd

www.thepeninsulaqatar.com BUSINESS | 21 SPORT | 27 Qatar & Canada Loss to Al Rayyan to boost bilateral add to Al Wakra's investments woes Sunday 5 March 2017 | 6 Jumada II 1438 Volume 21 | Number 7091 | 2 Riyals British rider wins CHI Al Shaqab event Emir holds phone Faster renewal talks with Bahrain King of licence mir H H Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani Eheld a telephone con- versation with H M King Hamad bin Issa Al Khalifa of for retailers Bahrain. King Hamad expressed satisfaction with the positive ministry’s website (https://serv- outcomes of the visit by Prime Ministry initiative ices.mec.gov.qa) should upload Minister of Bahrain, Prince The initiative is one the following documents: a Khalifa bin Salman Al Khal- of numerous smart copy of the identification ifa to Qatar, which reaffirmed electronic services papers of the applicant and both countries leaderships' that the Ministry has business owner; third-party keenness on cementing fra- launched to develop approvals (for certain activities, ternal bonds and promoting if applicable); and Civil Defence cooperation for the interests the business approval (for certain sites, if of their people. The two lead- environment in applicable). After the payment ers also discussed the latest Qatar. of fees, the licence is instantly regional developments. Retailers have hailed emailed to the address regis- The Emir in turn wel- tered at the Ministry. H E Sheikh Joaan bin Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, President of Qatar Olympic Committee, comed the intended visit of the Ministry initiative Applicants can also visit the presenting the trophy to Scott Brash of Great Britain, winner of the CSI5* event at the CHI Bahrain's Crown Prince, Dep- hoping it would help Ministry headquarters in Lusail, Al Shaqab, at Al Shaqab Arena yesterday. -

Advisory Mission to the World Heritage Site of the Historic Centre of Florence, Italy

REPORT JOINT UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE CENTRE/ ICOMOS ADVISORY MISSION TO THE WORLD HERITAGE SITE OF THE HISTORIC CENTRE OF FLORENCE, ITALY 22-25 May 2017 Cover: View across the city towards Santa Croce, from the belvedere of the Bardini Garden This report is jointly prepared by the mission members: Ms Isabelle Anatole-Gabriel (UNESCO World Heritage Centre) and Mr Paul Drury (ICOMOS International). 2 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................. 6 1. BACKGROUND TO THE MISSION ........................................................................................... 8 2. NATIONAL AND LOCAL POLICY FOR PRESERVATION AND MANAGEMENT ...... 9 3. IDENTIFICATION AND ASSESSMENT OF ISSUES .............................................................. 10 3.1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 10 3.2. Airport expansion ................................................................................................................... 11 3.3. The High Speed Rail Link ...................................................................................................... 12 3.4. Mobility in the historic centre and the developing tram system .................................. 13 Context ................................................................................................................................................ -

U.S., European Mayors Unite to Fight Antisemitism

U.S., EUROPEAN MAYORS UNITE TO FIGHT ANTISEMITISM As U.S. and European leaders have acknowledged, SLOVAKIA Lowell – Rodney M. Elliott Rye Brook – Paul S. Rosenberg EUROPEAN MAYORS AND MUNICIPAL LEADERS Bratislava – Ivo Nesrovnal Malden – Gary Christenson Southold – Scott A. Russell Mendon – Mark Reil Suffolk County – Steven Bellone antisemitism is on the rise. In response, AJC reached SLOVENIA ALBANIA Landsberg am Lech – Mathias Neuner Methuen – Steve Zanni Syracuse – Stephanie Miner Ljubljana – Zoran Janković out to mayors across Europe and the U.S., urging Berat – Petrit Sinaj Leipzig – Burkhard Jung Monterey – Scott J. Jenssen Wesley Hills – Marshall Katz Korçë - Sotiraq Filo Leverkusen – Uwe Richrath SPAIN Needham – Maurice P. Handel Westchester County – Robert P. – Manuela Carmena them to publicly condemn and take concrete actions Lushnjë – Fatos Tushe Lingen/Ems – Dieter Krone Madrid Newburyport – Donna D. Holaday Astorino Patos – Rajmonda Balilaj Ludwigshafen – Eva Lohse SWEDEN Newton – Setti Warren White Plains – Tom Roach against this pathology. These 188 European mayors – Paul M. Ehrbar Roskovec – Majlinda Bufi Maintal – Monika Böttcher Stockholm – Karin Wanngard Northampton – David Narkewicz Williston Park from 31 countries, representing over 67 million people, Tirana – Erion Veliaj Mainz – Michael Ebling Norwood – Paul A. Bishop Yonkers – Mike Spano Mannheim – Peter Kurz SWITZERLAND AUSTRIA Plympton – Mark E. Russo NORTH CAROLINA Marzahn Hellersdorf – Stefan Komoß Biel – Erich Fehr and 319 U.S. mayors and municipal leaders from 50 Quincy – Thomas P. Koch Asheville – Esther E. Manheimer Salzburg – Heinz Schaden Lausanne Meppen – Helmut Knurbein – Daniel Rizzo Vienna – Michael Häupl Revere Charlotte – Daniel G. Clodfelter states and the District of Columbia, representing over Mitte – Christian Hanke Salem – Kimberley Driscoll Villach – Günther Albel NORTH DAKOTA Monheim am Rhein – Daniel Sandisfield – Alice B. -

DARIO NARDELLA Extended Bio

DARIO NARDELLA Extended Bio Born in Torre del Greco, Neaples in 1975, Dario Nardella has been living in Florence Since 1989. Married to Chiara, a French- Italian political analyst who is now a prominent entrepreneur in children's education services, he is father of two children, Cosimo 6 and Amélie 2. Since he was a child, Dario showed his passion for music which led him to the Florence music academy - "Lorenzo Cherubini", where he became a violinist in 1998. He graduated "magna cum laude" in Law at the University of Florence where he got his PhD in Constitutional Law and Environmental Law, and where he is currently Cultural Property Law professor. In 2004 he is the youngest councilman elected for the Democratic Party, with the highest number of preferences in the Florence City Hall and he is appointed president of the Commission for cultural policy, education and sport. From 2006 to 2008 he is also legislative advisor for the Minister of Institutional Reforms in Prime Minister Romano Prodi's cabinet. During the same years he is selected by the US Department of State to join the ’”International Visitor Leadership Program”. Dario is elected again in 2009 and appointed Deputy Mayor of Florence, by Mayor Matteo Renzi, with special mandate as Commissioner for Economic development and Sport. During his mandate, not with standing the general financial crisis, the City of Florence reaches the highest rate of international agreements and international partnerships . In December 2012 he runs for primary elections and is elected Member of Parliament in February 2013. He is currently member of the Parliament Commission for Economic Affairs and Development. -

I Sindaci Delle Città Metropolitane Chiedono Un Tavolo Politico Con Il Presidente Draghi

ASSOCIAZIONE NAZIONALE COMUNI ITALIANI PORTAVOCE DEL PRESIDENTE COMUNICATO STAMPA I sindaci delle Città metropolitane chiedono un tavolo politico con il Presidente Draghi. Risorse dirette e responsabilità chiare Noi sindaci delle grandi Città, a nome dei sindaci di tutti i Comuni italiani riuniti oggi nel Coordinamento ANCI dei Sindaci metropolitani, ribadiamo la necessità di veder riconosciute direttamente ai Comuni e alle Città le risorse del PNRR (Piano Nazionale Resilienza e Ripartenza). Ad oggi è insufficiente il ruolo riservato dal Dl Governance e Semplificazioni a Comuni e Città metropolitane. Chiediamo di partecipare direttamente e senza intermediazione alla gestione di alcune missioni di progetti, perché in questi anni abbiamo dato ampia dimostrazione di saper gestire gli investimenti con efficacia ed efficienza. Chiediamo che i finanziamenti siano diretti e non necessariamente intermediati dalle Regioni, applicando modelli di gestione già sperimentati dal Governo in occasione del Patto delle Città Metropolitane e del Pon Metro. Chiediamo riparti diretti con assegnazione automatica per classe demografica, stanziamenti a sportello su programmi nazionali e il finanziamento di progetti cosiddetti bandiera. Vogliamo fare il nostro lavoro e il nostro dovere per spendere bene e rapidamente le risorse; non accettiamo di aspettare anni di burocrazia e procedure per sapere chi fa che cosa. A ciascuno il suo: ogni livello di governo sia responsabile delle misure e delle risorse assegnate e garantisca tempi ed efficienza per gli interventi. Il rischio concreto è che altrimenti non si riusciranno a spendere le risorse alle condizioni che pone la Commissione Ue. I cittadini hanno l’esigenza di vedere cantierizzati al più presto i progetti, quale risposta concreta generata sui territori dalle risorse assegnate dal PNRR. -

Città Metropolitane, Nardella: 'Il Governo Ri Nanzi Il Bando Periferie E

23/9/2019 Città Metropolitane, Nardella: 'Il governo rifinanzi il Bando Periferie e il Pon Metro' - 055Firenze Questo sito utilizza cookie per migliorare l'esperienza utente e motivi statistici. Utilizzando il sito, l'utente accetta l'uso dei cookie in conformità con le nostre linee guida. Per saperne di più clicca qui. Accetta cookie Città Metropolitane, Nardella: 'Il governo rinanzi il Bando Periferie e il Pon Metro' CRONACA 21/09/2019 Nardella all'incontro con i sindaci delle Città Metropolitane https://www.055firenze.it/art/192335/Citt-Metropolitane-Nardella-governo-rifinanzi-Bando-Periferie-Metro 1/7 23/9/2019 Città Metropolitane, Nardella: 'Il governo rifinanzi il Bando Periferie e il Pon Metro' - 055Firenze Il coordinamento Anci dei Sindaci delle Città Metropolitane, presieduto ieri mattina a Bari dal Sindaco Dario Nardella, ha fatto il punto sullo stato di crescita delle Metrocittà e, come sottolinea il Sindaco di Firenze, "ha puntualizzato l'esigenza di rinanziare il Bando Periferie e il Pon Metro, due strumenti che si sono rivelati particolarmente utili alla promozione strategica dei nostri territori". "Noi - ha sottolineato Nardella - chiediamo all'esecutivo di completare questa riforma che è rimasta a metà strada. Manca una eettiva autonomia scale delle città metropolitane che così dipendono soltanto dalle decisioni di Roma sui trasferimenti. Manca una identità chiara dal punto di vista delle competenze e questo genera spesso confusione tra Regioni - Città metropolitane e altre Province, e poi manca una agenda nazionale che consenta alle Città metropolitane di essere il cuore dell'agenda urbana, di essere dei grandi motori di sviluppo per le infrastrutture, per la riqualicazione delle periferie". -

Final Statement of the European Mayors' Summit on Europe: Refugees Are Our Brothers and Sisters

Final Statement of the European Mayors' Summit on Europe: Refugees are our Brothers and Sisters The European cities we represent are clusters of towns that existed even before their respective nations, many of them even before Christianity, such as Athens and Rome, Valencia, Zaragoza, Barcelona, Malaga, Palermo, Naples, Mytilene (Lesbos) and Lampedusa. Some of these cities have been able to create forms of coexistence and acceptance that today are models to imitate: Athens, for example, is at the origin of modern democracy; Florence is a leader in the abolition of the death penalty. In general and following the message of Christ, being European also means recognising each person’s human dignity and freedom, with peace as the supreme good. When dealing with our obligations towards refugees, we must remember the ways in which we organized ourselves in cities first and subsequently as nations during the course of history. The great cities of Europe – as well as those of the Americas and Asia – which now face the worst crisis of displacement since World War II, must continue to collaborate in good faith, trust, hope, friendship, harmony and justice, to embrace humanity, integration and solidarity. This European awareness, present in the representatives of cities, points to the need of creating a network of Mayors capable of conceiving welcoming cities as shelters, capable of organizing safe and regular humanitarian corridors within the European Union, recognized by the international community, and capable of expressing solidarity. Mayors, collectively empowered, could better exercise their responsibilities in a more harmonious way with regional, national and international levels of government. -

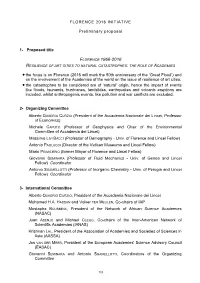

Preliminary Proposal to IAP

FLORENCE 2016 INITIATIVE Preliminary proposal 1- Proposed title FLORENCE 1966-2016 RESILIENCE OF ART CITIES TO NATURAL CATASTROPHES: THE ROLE OF ACADEMIES • the focus is on Florence (2016 will mark the 50th anniversary of the ‘Great Flood’) and on the involvement of the Academies of the world on the issue of resilience of art cities; • the catastrophes to be considered are of ‘natural’ origin, hence the impact of events like floods, tsunamis, hurricanes, landslides, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions are included, whilst anthropogenic events, like pollution and war conflicts are excluded. 2- Organizing Committee Alberto QUADRIO CURZIO (President of the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Professor of Economics) Michele CAPUTO (Professor of Geophysics and Chair of the Environmental Committee of Accademia dei Lincei) Massimo LIVI BACCI (Professor of Demography - Univ. of Florence and Lincei Fellow) Antonio PAOLUCCI (Director of the Vatican Museums and Lincei Fellow) Mario PRIMICERIO (former Mayor of Florence and Lincei Fellow) Giovanni SEMINARA (Professor of Fluid Mechanics - Univ. of Genoa and Lincei Fellow) Coordinator Antonio SGAMELLOTTI (Professor of Inorganic Chemistry - Univ. of Perugia and Lincei Fellow) Coordinator 3- International Committee Alberto QUADRIO CURZIO, President of the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei Mohamed H.A. HASSAN and Volker TER MEULEN, Co-chairs of IAP Mostapha BOUSMINA, President of the Network of African Science Academies (NASAC) Juan ASENJO and Michael CLEGG, Co-chairs of the Inter-American Network of Scientific Academies (IANAS) Krishnan LAL, President of the Association of Academies and Societies of Sciences in Asia (AASSA) Jos VAN DER MEER, President of the European Academies' Science Advisory Council (EASAC) Giovanni SEMINARA and Antonio SGAMELLOTTI, Coordinators of the Organizing Committee 1/3 4- Date 11 - 12 October 2016 5- Venue Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Palazzo Corsini, Rome 6- Structure of the meeting We propose the following structure of the meeting.