Media Naturalness and the Ability to Predict Generosity in a Give-Some – Get-Some Interaction1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modularity As a Concept Modern Ideas About Mental Modularity Typically Use Fodor (1983) As a Key Touchstone

COGNITIVE PROCESSING International Quarterly of Cognitive Science Mental modularity, metaphors, and the marriage of evolutionary and cognitive sciences GARY L. BRASE University of Missouri – Columbia Abstract - As evolutionary approaches in the behavioral sciences become increasingly prominent, issues arising from the proposition that the mind is a collection of modular adaptations (the multi-modular mind thesis) become even more pressing. One purpose of this paper is to help clarify some valid issues raised by this thesis and clarify why other issues are not as critical. An aspect of the cognitive sciences that appears to both promote and impair progress on this issue (in different ways) is the use of metaphors for understand- ing the mind. Utilizing different metaphors can yield different perspectives and advancement in our understanding of the nature of the human mind. A second purpose of this paper is to outline the kindred natures of cognitive science and evolutionary psychology, both of which cut across traditional academic divisions and engage in functional analyses of problems. Key words: Evolutionary Theory, Cognitive Science, Modularity, Metaphors Evolutionary approaches in the behavioral sciences have begun to influence a wide range of fields, from cognitive neuroscience (e.g., Gazzaniga, 1998), to clini- cal psychology (e.g., Baron-Cohen, 1997; McGuire and Troisi, 1998), to literary theory (e.g., Carroll, 1999). At the same time, however, there are ongoing debates about the details of what exactly an evolutionary approach – often called evolu- tionary psychology— entails (Holcomb, 2001). Some of these debates are based on confusions of terminology, implicit arguments, or misunderstandings – things that can in principle be resolved by clarifying current ideas. -

Biogeography and Ecology of New Guinea Edited by J.L. Gressitt Dr W

Book reviews Biogeography and Ecology of New of documentation, analysis and interpretation is Guinea put over with a style and spirit that prevents such a Edited by J.L. Gressitt heavyweight work from becoming too stodgy. Dr W. Junk, 2 vols, US $195, DFL.450 Norman Myers The opening sentence of this splendid work sums it up: 'New Guinea is a fantastic island, unique Darwinism Defended; a guide to the and fascinating'. The largest tropical island and evolution controversies the highest island (with glaciers), it features Michael Ruse extraordinary bio-ecological diversity: some 9000 species of plants, many of them endemic; Addison Wesley, £6-95 more than 200 mammals, almost two-thirds of For a century it has been taken for granted that which are unique to the island; at least 570 birds; Darwin had solved the question to why there is a 170 lizards; 200 frogs; probably 10,000 species of myriad of species on earth. Many people now beetles, and around 20,000 species of other think otherwise and the theory of evolution by arthropods. Yet these figures, remarkable as they natural selection is under assault from several are, refer only to known and documented branches of enquiry; some philosophers think species: the numbers awaiting scientific attention that the theory is nothing more than empty could well be much greater. Along the southern rhetoric, some scientists think evolution occurs in edge of the island the climate is seasonal, thus jerks and thus negates the gradualist requirement engendering ecological variety, and the geologic of Darwin's theory and others believe that the upheavals of the recent past have induced patterns of life on earth are by the hand of an sufficient 'creative disruption' to stimulate the omniscient creator. -

The Evolutionary Biology of Decision Making

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, Department of Psychology Psychology, Department of 2008 The Evolutionary Biology of Decision Making Jeffrey R. Stevens University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/psychfacpub Part of the Psychiatry and Psychology Commons Stevens, Jeffrey R., "The Evolutionary Biology of Decision Making" (2008). Faculty Publications, Department of Psychology. 523. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/psychfacpub/523 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Psychology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Department of Psychology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in BETTER THAN CONSCIOUS? DECISION MAKING, THE HUMAN MIND, AND IMPLICATIONS FOR INSTITUTIONS, ed. Christoph Engel and Wolf Singer (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008), pp. 285-304. Copyright 2008 Massachusetts Institute of Technology & the Frankfurt Institute for Advanced Studies. Used by permission. 13 The Evolutionary Biology of Decision Making Jeffrey R. Stevens Center for Adaptive Behavior and Cognition, Max Planck Institute for Human Development, 14195 Berlin, Germany Abstract Evolutionary and psychological approaches to decision making remain largely separate endeavors. Each offers necessary techniques and perspectives which, when integrated, will aid the study of decision making in both humans and nonhuman animals. The evolutionary focus on selection pressures highlights the goals of decisions and the con ditions under which different selection processes likely influence decision making. An evolutionary view also suggests that fully rational decision processes do not likely exist in nature. -

Emerald Jrit Jrit628638 164..182

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: www.emeraldinsight.com/2397-7604.htm JRIT&L 12,2 Facilitating success for people with mental health issues in a college through cognitive 164 remediation therapy and social Received 19 January 2019 Revised 22 April 2019 and emotional learning Accepted 6 May 2019 Jaswant Kaur Bajwa CPLS, George Brown College – Saint James Campus, Toronto, Canada Bobby Bajwa Department of Medical Sciences, University of Western Ontario, London, Canada, and Taras Gula CPLS, George Brown College – Saint James Campus, Toronto, Canada Abstract Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to describe the components, structure and theoretical underpinnings of a cognitive remediation intervention that was delivered within a supported education program for mental health survivors. Design/methodology/approach – In total, 21 participants enrolled in the course Strengthening Memory, Concentration and Learning (PREP 1033 at George Brown College (GBC)) with the diagnosis of depression, anxiety, PTSD, ED and substance use disorder were included in the research. After a baseline assessment, participants completed 14 week cognitive remediation training (CRT) protocol that included six essential components that were integrated and implemented within the course structure of the supported education program at GBC. This was followed by a post-training assessment. Findings – Analysis of the participants’ performance on CRT protocol using computerized games showed little significant progress. However, the research found a positive change in the self-esteem of the participants that was statistically significant and the findings also aligned with the social and emotional learning framework. Research limitations/implications – One of the limitations in the research was the use of computer- assisted cognitive remediation in the form of the HappyNeuron software. -

Evolution by Natural Selection, Formulated Independently by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace

UNIT 4 EVOLUTIONARY PATT EVOLUTIONARY E RNS AND PROC E SS E Evolution by Natural S 22 Selection Natural selection In this chapter you will learn that explains how Evolution is one of the most populations become important ideas in modern biology well suited to their environments over time. The shape and by reviewing by asking by applying coloration of leafy sea The rise of What is the evidence for evolution? Evolution in action: dragons (a fish closely evolutionary thought two case studies related to seahorses) 22.1 22.4 are heritable traits that with regard to help them to hide from predators. The pattern of evolution: The process of species have changed evolution by natural and are related 22.2 selection 22.3 keeping in mind Common myths about natural selection and adaptation 22.5 his chapter is about one of the great ideas in science: the theory of evolution by natural selection, formulated independently by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace. The theory explains how T populations—individuals of the same species that live in the same area at the same time—have come to be adapted to environments ranging from arctic tundra to tropical wet forest. It revealed one of the five key attributes of life: Populations of organisms evolve. In other words, the heritable characteris- This chapter is part of the tics of populations change over time (Chapter 1). Big Picture. See how on Evolution by natural selection is one of the best supported and most important theories in the history pages 516–517. of scientific research. -

Microevolution and the Genetics of Populations Microevolution Refers to Varieties Within a Given Type

Chapter 8: Evolution Lesson 8.3: Microevolution and the Genetics of Populations Microevolution refers to varieties within a given type. Change happens within a group, but the descendant is clearly of the same type as the ancestor. This might better be called variation, or adaptation, but the changes are "horizontal" in effect, not "vertical." Such changes might be accomplished by "natural selection," in which a trait within the present variety is selected as the best for a given set of conditions, or accomplished by "artificial selection," such as when dog breeders produce a new breed of dog. Lesson Objectives ● Distinguish what is microevolution and how it affects changes in populations. ● Define gene pool, and explain how to calculate allele frequencies. ● State the Hardy-Weinberg theorem ● Identify the five forces of evolution. Vocabulary ● adaptive radiation ● gene pool ● migration ● allele frequency ● genetic drift ● mutation ● artificial selection ● Hardy-Weinberg theorem ● natural selection ● directional selection ● macroevolution ● population genetics ● disruptive selection ● microevolution ● stabilizing selection ● gene flow Introduction Darwin knew that heritable variations are needed for evolution to occur. However, he knew nothing about Mendel’s laws of genetics. Mendel’s laws were rediscovered in the early 1900s. Only then could scientists fully understand the process of evolution. Microevolution is how individual traits within a population change over time. In order for a population to change, some things must be assumed to be true. In other words, there must be some sort of process happening that causes microevolution. The five ways alleles within a population change over time are natural selection, migration (gene flow), mating, mutations, or genetic drift. -

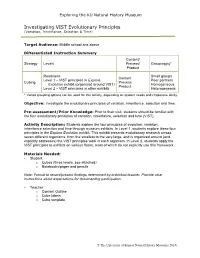

Investigating VIST Evolutionary Principles (Variation, Inheritance, Selection & Time)

Exploring the KU Natural History Museum Investigating VIST Evolutionary Principles (Variation, Inheritance, Selection & Time) Target Audience: Middle school and above Differentiated Instruction Summary Content/ Strategy Levels Process/ Grouping(s)* Product Readiness Small groups Content Level 1 – VIST principles in Explore Peer partners Cubing Process Evolution exhibit (organized around VIST) Homogeneous Product Level 2 – VIST principles in other exhibits Heterogeneous * Varied grouping options can be used for this activity, depending on student needs and chaperone ability. Objective: Investigate the evolutionary principles of variation, inheritance, selection and time. Pre-assessment/Prior Knowledge: Prior to their visit, students should be familiar with the four evolutionary principles of variation, inheritance, selection and time (VIST). Activity Description: Students explore the four principles of evolution: variation, inheritance selection and time through museum exhibits. In Level 1, students explore these four principles in the Explore Evolution exhibit. This exhibit presents evolutionary research across seven different organisms, from the smallest to the very large, and is organized around (and explicitly addresses) the VIST principles work in each organism. In Level 2, students apply the VIST principles to exhibits on various floors, most of which do not explicitly use this framework. Materials Needed: • Student o Cubes (three levels, see attached) o Notebooks/paper and pencils Note: Format to record/present findings determined by individual teacher. Provide clear instructions about expectations for documenting participation. • Teacher o Content Outline o Cube labels o Cube template © The University of Kansas Natural History Museum (2014) Exploring the KU Natural History Museum Content: VIST* Overview There are four principles at work in evolution—variation, inheritance, selection and time. -

James K. Wetterer

James K. Wetterer Wilkes Honors College, Florida Atlantic University 5353 Parkside Drive, Jupiter, FL 33458 Phone: (561) 799-8648; FAX: (561) 799-8602; e-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON, Seattle, WA, 9/83 - 8/88 Ph.D., Zoology: Ecology and Evolution; Advisor: Gordon H. Orians. MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY, East Lansing, MI, 9/81 - 9/83 M.S., Zoology: Ecology; Advisors: Earl E. Werner and Donald J. Hall. CORNELL UNIVERSITY, Ithaca, NY, 9/76 - 5/79 A.B., Biology: Ecology and Systematics. UNIVERSITÉ DE PARIS III, France, 1/78 - 5/78 Semester abroad: courses in theater, literature, and history of art. WORK EXPERIENCE FLORIDA ATLANTIC UNIVERSITY, Wilkes Honors College 8/04 - present: Professor 7/98 - 7/04: Associate Professor Teaching: Biodiversity, Principles of Ecology, Behavioral Ecology, Human Ecology, Environmental Studies, Tropical Ecology, Field Biology, Life Science, and Scientific Writing 9/03 - 1/04 & 5/04 - 8/04: Fulbright Scholar; Ants of Trinidad and Tobago COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, Department of Earth and Environmental Science 7/96 - 6/98: Assistant Professor Teaching: Community Ecology, Behavioral Ecology, and Tropical Ecology WHEATON COLLEGE, Department of Biology 8/94 - 6/96: Visiting Assistant Professor Teaching: General Ecology and Introductory Biology HARVARD UNIVERSITY, Museum of Comparative Zoology 8/91- 6/94: Post-doctoral Fellow; Behavior, ecology, and evolution of fungus-growing ants Advisors: Edward O. Wilson, Naomi Pierce, and Richard Lewontin 9/95 - 1/96: Teaching: Ethology PRINCETON UNIVERSITY, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology 7/89 - 7/91: Research Associate; Ecology and evolution of leaf-cutting ants Advisor: Stephen Hubbell 1/91 - 5/91: Teaching: Tropical Ecology, Introduction to the Scientific Method VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY, Department of Psychology 9/88 - 7/89: Post-doctoral Fellow; Visual psychophysics of fish and horseshoe crabs Advisor: Maureen K. -

Information Systems Theorizing Based on Evolutionary Psychology: an Interdisciplinary Review and Theory Integration Framework1

Kock/IS Theorizing Based on Evolutionary Psychology THEORY AND REVIEW INFORMATION SYSTEMS THEORIZING BASED ON EVOLUTIONARY PSYCHOLOGY: AN INTERDISCIPLINARY REVIEW AND THEORY INTEGRATION FRAMEWORK1 By: Ned Kock on one evolutionary information systems theory—media Division of International Business and Technology naturalness theory—previously developed as an alternative to Studies media richness theory, and one non-evolutionary information Texas A&M International University systems theory, channel expansion theory. 5201 University Boulevard Laredo, TX 78041 Keywords: Information systems, evolutionary psychology, U.S.A. theory development, media richness theory, media naturalness [email protected] theory, channel expansion theory Abstract Introduction Evolutionary psychology holds great promise as one of the possible pillars on which information systems theorizing can While information systems as a distinct area of research has take place. Arguably, evolutionary psychology can provide the potential to be a reference for other disciplines, it is the key to many counterintuitive predictions of behavior reasonable to argue that information systems theorizing can toward technology, because many of the evolved instincts that benefit from fresh new insights from other fields of inquiry, influence our behavior are below our level of conscious which may in turn enhance even more the reference potential awareness; often those instincts lead to behavioral responses of information systems (Baskerville and Myers 2002). After that are not self-evident. This paper provides a discussion of all, to be influential in other disciplines, information systems information systems theorizing based on evolutionary psych- research should address problems that are perceived as rele- ology, centered on key human evolution and evolutionary vant by scholars in those disciplines and in ways that are genetics concepts and notions. -

The Role of Theory of Mind As a Mediator in The

THE ROLE OF THEORY OF MIND AS A MEDIATOR IN THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SOCIAL FUNCTIONING AND SCHIZOTYPY A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Marielle Divilbiss December 2009 Thesis written by Marielle Divilbiss B.A., DePaul University, 2007 M.A., Kent State University, 2009 Approved by Nancy Docherty, Ph.D.,_______________________ Advisor Douglas Delahanty, Ph.D.,_____________________ Chair, Department of Psychology Timothy Moerland, Ph.D.,_____________________ Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii Table of Contents List of figures…………………………………………………………………………… v List of tables……………………………………………………………………………. vi Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………………… vii Introduction…………………………………………………………………………….. 1 Hypotheses……………………………………………………………………….......... 11 Method…………………………………………………………………………………. 13 Results………………………………………………………………………………….. 21 Table 1………………………………………………………………………………….. 22 Table 2………………………………………………………………………………….. 23 Table 3………………………………………………………………………………….. 24 Table 4………………………………………………………………………………….. 25 Table 6…………………………………………………………………………………. 26 Table 7…………………………………………………………………………………. 27 Table 8…………………………………………………………………………………. 28 Table 9…………………………………………………………………………………. 32 Table 10……………………………………………………………………………….. 33 Table 11……………………………………………………………………………….. 37 Figure 1………………………………………………………………………………... 38 Table 12………………………………………………………………………………. 40 iii Figure 2………………………………………………………………………………… 41 Discussion…………………………………………………………………………….. 42 Conclusions…………………………………………………………………………… -

The Biological Roots of Morality*

The Biological Roots of Morality* FRANCISCO J. AYALA Department of Genetics University of California Davis, California 95616 U.S.A. ABSTRACT: The question whether ethical behavior is biologically determined may refer either to the capacity for ethics (i.e., the proclivity to judge human actions as either right or wrong), or to the moral norms accepted by human beings for guiding their actions. My theses are: (1) that the capacity for ethics is a necessary attribute of human nature; and (2) that moral norms are products of cultural evolution, not of biological evolution. Humans exhibit ethical behavior by nature because their biological makeup determines the presence of the three necessary, and jointly sufficient, conditions for ethical behavior: (i) the ability to anticipate the consequences of one's own actions; (ii) the ability to make value judgments; and (iii) the ability to choose between alternative courses of action. Ethical behavior came about in evolution not because it is adaptive in itself, but as a necessary consequence of man's eminent intellectual abilities, which are an attribute directly promoted by natural selection. Since Darwin's time there have been evolutionists proposing that the norms of morality are derived from biological evolution. Sociobiologists represent the most recent and most subtle version of that proposal. The sociobiologists' argument is that human ethical norms are sociocultural correlates of behaviors fostered by biological evolution. I argue that such proposals are misguided and do not escape the naturalistic fallacy. The isomorphism between the behaviors promoted by natural selection and those sanctioned by moral norms exists only with respect to the consequences of the behaviors; the underlying causations are completely disparate. -

Emergence Discussion

23/10/2011 IAJS Discussion Seminar with George Hogenson – Introduction by Warren Colman NB: To access and download two papers by George Hogenson which will form the basis for the discussion, please go to the following links: ‘What are symbols symbols of’: http://bit.ly/gxKn6T ‘The self, the symbolic and synchronicity’ http://bit.ly/gj13OQ It’s a great pleasure for me to introduce George Hogenson who will be leading a seminar for the IAJS list on the theme of ‘emergence’. He has been well known in the Jungian world long before he became an analyst as the author of Jung’s Struggle with Freud (1983), an impressive and scholarly work that analysed Jung’s break from Freud in terms of the creation of a different mythological understanding of time, death and authority. At that time, George was a philosophy PhD and a teacher of political philosophy, specialising in the field of international peace and security. From this strong academic background, George became interested in pursuing the practice of psychotherapy as well as its theory and qualified as a Jungian analyst in Chicago in 1998. In 2001, George gave a plenary presentation at the IAAP Congress in Cambridge, England, debating with Anthony Stevens on the nature and origins of archetypes. This was my first introduction both to George and to the dynamic systems theory he proposed as a way of reconceptualising archetypal theory and challenging Stevens’ use of evolutionary psychology as a way of bolstering the classical ‘blueprint’ model of archetypes as a priori structures. George’s presentation of a short video from the field of robotics, illustrating the principles of self-organisation was a revelation to me: I well remember the feeling that I was seeing a vision of the future, an entirely new way of thinking that had the potential to revision and revitalise analytical psychology.