Not Exactly the 'Comforts of Home'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NOZZOM NEWSLETTER ISSUE #26 - June 2016 Moving… Foreword Contents Welcome to Our New Issue of Nozzom, Where We Share with You Our Events, Projects and Plans

NOZZOM NEWSLETTER ISSUE #26 - June 2016 Moving… Foreword Contents Welcome to our new issue of Nozzom, where we share with you our events, projects and plans. During the past few months, Giza Systems’ Group of Companies undertook a series of exciting new projects, which will be reported in the coming pages. Since we foresee that 2016 is a big year for technology in our region – with governments’ headline missions to provide the utmost support to 04 those who bring advancement – we at Giza Systems are thrilled to be part of this great dynamic. With technological solutions directly targeted NOZZOM NEWSLETTER ISSUE #26 at supporting national development; as well as innovative global partnerships that will allow us to significantly empower our region; we’ve got New Leaps our eye on the best for the future. Our vision to inspire better prospects with generations ready to excel, create, and innovate still goes strong, as the possibilities unfold before Chairman us. With the opening of Fab Lab New Cairo branch at our headquarters, we continue to foster creativity, as well as create a space for innovation and collaboration in the community. Through bringing technology to the masses, we aim at empowering a technology-savvy generation, Shehab ElNawawi helping them compete in a dynamic and continuously changing world, and turning their dreams into tangible realities. The articles and items in this issue include a wide variety of topics that affect all our stakeholders in some way. We aim at continuously Managing Editor improving our portfolio of offerings, as well as adhering to the highest quality standards in everything we do. -

HABARI INFORMATION OM TANZANIA 51 Årg

HABARI INFORMATION OM TANZANIA 51 årg Nr 2/2019 Tema: Kultur Ur innehållet: Kulturturism, Elieshi om litteraturen, Tingatinga, Makonde ... TIDNINGEN HABARI SVETAN ORDFÖRANDEN utges av www.svetan.org SVENSKTANZANISKA www.facebook.com/ FÖRENINGEN c/o Harriet Rehn SVETAN Edeby Ängsväg 23 741 91 KNIVSTA REDAKTION epost: [email protected] *** Lars Asker, redaktör tel 08-38 48 55, mobil 0705 85 23 10 STYRELSE [email protected] [email protected] Eva Löfgren tel 08-36 48 88, mobil 0702 11 98 68 Harriet Rehn, ordförande [email protected] [email protected] Sten Löfgren tel 08-36 48 88, mobil 0708 90 59 59 Rehema Prick, vice ordförande [email protected] [email protected] Välkomna till detta temanummer Linus Dunkers, sekreterare av Habari, denna gång med temat PRISUPPGIFTER 2019 [email protected] Kultur. Här kan ni läsa om tan- Martha Andersson, kassör zanisk litteratur, konst och mu- SVETAN-medlemskap inkl HABARI 300 kr [email protected] sik. Därtill får ni bekanta er med Medlemskap exkl HABARI 100 kr Jeanette Olsson, ledamot/ kulturens roll i projektet Tumaini Familjemedlem exkl HABARI 50 kr Tumaini Children´s Center. De flesta av [email protected] Ungdomsmedlemskap 150 kr oss som vistats och besökt Tan- Prenumeration HABARI 250 kr Emma Kreü, ledamot [email protected] zania har inte kunnat undgå att Enstaka HABARI 50 kr lära känna Tinga Tinga och Ma- (Äldre nummer pris efter överenskommelse) Daniel Saulli, ledamot [email protected] konde-konsten. Tanzania har ock- Betala in korrekt belopp på SVETANs plusgiro 35 95 501 Prosper Kaberwa, ledamot så en bred musikkultur med allt – ange på talongen vad som önskas. -

Africa Market Reporttm

AFRICA ART MARKET REPORTTM MODERN / CONTEMPORARY / DESIGN 2015 TaBLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION R ECENT INITIATIVES RANKING DESIGN MARKET & INVESTMENTS HIGHLIGHTS CORPORATE COLLECTIONS FOCUS 2015 TEACH THE FUTURE 3 Why did you decide to include a talk about Africa’s art scenes in last year’s Conversations? Because the developments within the African art scene INTRODUCTION are hugely interesting for us, our galleries and the collectors who come to our fair, and it ran in parallel to the first Venice Biennale curated by an African, Okwui Enwezor. In the global art market, what margin do you think FROM DISREGARD TO NORMAL ART the Nigerians Aina Onabolu (1882-1963) art by African artists represents? and Ben Enwonwu (1917-1994) are worth I am probably not the best person to answer this During the last 10 years, modern and citing as they instigated change towards question, but it seems fair to guess that the margin is contemporary African art has found an openness regarding classical arts, known still rather small. However, the international interest enthusiastic audience both on the conti- as “primitive arts”. from curators and patrons about the art scenes across nent and internationally. Significantly, this Africa is growing, as is the number of potential collectors includes important institutions. Taking an The notion of contemporary art emerged across the continent, and so its market seemed poised for expansion. interest in the viewpoint of the market and in the 1960s, regrouping the diversity institutions enables the structural issues of artistic production on the continent. It What’s your perspective on the African market and initiated changes to be known and consists of a large, variegated whole irriga- in terms of its artists, collectors and other understood, and for the role of African ted by three types of training: autodidact, professionals, and what how do you think this will develop? artists and those working in this context including famous artist such as Moké from to be situated. -

ARTIST FELLOWSHIP SAMPLE PACKET What Follows Is a Range of Applicant Responses to Artist Fellowship Application Prompts

ARTIST FELLOWSHIP SAMPLE PACKET What follows is a range of applicant responses to Artist Fellowship application prompts. Artist Fellowship applications are scored based on Artistic Merit, and Artistic Quality in Technique and Technical Skills, Creativity, Originality, and Work Samples. While each criteria is scored individually on a scale of 1 (poor) – 5 (excellent), please consider that for a grant evaluator, the separate criteria also work together to give the most complete picture of an artist applicant. Artist Statement* Write an Artist Statement describing your artistic style and who you are as an artist (1000 characters with spaces) Artist Statement Sample #1 As an artist I explore and interpret ideas, emotions and experiences. A multilayered artwork can create a dialogue between the artist and the viewer and can be enjoyed on many levels. I look for the essential element or elements of a subject and find visual symbols for these elements and create a narrative. Some symbols are obvious universal symbols, some are personal symbols that I hope speak to the universal psyche, and many introduce themselves intuitively and can only be understood on an emotional level. Artwork is a process of inspiration, meditation, investigation, creation, interpretation and intuition. Mystery is essential to art and to life, it is what keeps us questioning and questing. Artist Statement Sample #2 I am a lyrical, autobiographical and spiritual poet. My subjects are ordinary people and places. My work has achieved regional acceptance and recognition from Academy of American Poets, PEN International, American Academy in Rome, Distinguished Artist Award from R2AC. Bringing my early poems into an energetic relationship with the new is the alchemical process needed to realize my mature artistic vision. -

Issued by the Britain-Tanzania Society No 101 Jan - April 2012

Tanzanian Affairs Text 1 Issued by the Britain-Tanzania Society No 101 Jan - April 2012 50th Anniversary of Independence Ambitious Plans to end Energy Crisis Bumpy Ride for the Constitution Big Gold - Thankyou & Goodbye ? Education - New Developments VSO - 50 years of Partnership A New National Anthem - Mungu Ibariki Africa Enoch Mankayi Sontonga God bless Africa God bless Tanzania* Bless its leaders Grant eternal Freedom and Let Wisdom, Unity and Unity to its sons and daughters. Peace be the shield of God bless Tanzania Africa and its people. and its people. Bless Africa Bless Tanzania Bless Africa Bless Tanzania Bless the children of Africa. Bless the children of Tanzania. *”Tanganyika” in 1961, changed to “Tanzania” following the Union cover photo: Prime Minister Julius Nyerere leaves Karimjee Hall in Dec 1961 and is enthusiastically greeted by his followers. TANZANIA IS FIFTY The last strains of the new national anthem die away. And across the dark bush and towering palms, over the roofs of clustered villages, even to Dar es Salaam, a blaze of coloured light four miles away echoes the triumphant roar with the incessant rumbling cries of Uhuru coming out from underneath. This is Tanganyika’s finest moment. A fragment of time to be savoured, treasured and stored in the memory. An experi- ence, emotional ... and unique. Tanganyika is independent; a nation is born ... So wrote Graham Hulley in The East African Annual 1962-63 ‘Climaxing a feat which caught the imagination of the world, Lieutenant Alexander Nyirenda climbed to the summit of the mighty Mount Kilimanjaro and lit a symbolic torch next to the new Tanganyikan flag. -

The Geographical Approach to the African Neighbourhood

Crisis and creativity: exploring the wealth of the African neighbourhood Konings, P.J.J.; Foeken, D.W.J. Citation Konings, P. J. J., & Foeken, D. W. J. (2006). Crisis and creativity: exploring the wealth of the African neighbourhood. Leiden: Brill. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/14740 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/14740 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). 1 The African neighbourhood: An introduction Piet Konings, Rijk van Dijk & Dick Foeken Introduction ‘Neighbourhood’ research goes back to the 1920s with the work of the sociolo- gists of the Chicago School. Urban space, they found, was segregated in ‘neighbourhoods’ based on the cultural background of immigrants. It was thought that this segregation would disappear as immigrants and their offspring assimilated in American culture. However, subsequent researchers found that urban space remained segregated, not based on cultural background but on class and race. Researchers found that the attachment to particular neighbourhoods also depended on various other aspects as well. They became more heterogene- ous, yet their names and boundaries remained the same, thus maintaining their distinctiveness vis-à-vis other neighbourhoods. This raises the question as to what constitutes a neighbourhood. Or what defines this ‘distinctiveness’ other than just a name and a boundary? Geogra- phers have many definitions, all of which can be grouped according to explana- tions that describe neighbourhoods as (1) homogeneous areas sharing demo- graphic or housing characteristics; (2) areas that may have diverse characteris- tics but whose residents share some cohesive sense of identity, political organi- zation or social organization; (3) housing sub-markets in which homes are considered close substitutes; and (4) small spatial units that do not necessarily have any of the above characteristics (Megbolugbe et al. -

Newsletter Events

INTERNATIONAL ACTIVITY ILT - Face to Face Teams Meeting in Portugal IC MEEITING 2019 in TANZANIA “we are adding yet another Grail saint to The Grail registration in the cloud of witnesses” UNFCCC Lucy Jones (USA) THE GRAIL INTERNATIONAL IT HAPPENED IN … NEWSLETTER EVENTS November 2018 This newsletter is intended to be a It's still November! And November is a time of two-way communication channel thanksgiving for the lives of our Grail sisters who have for Grail members to fill up the gone before us. Let their lives shine upon us while gaps between Crossroads with short news items and an events reminding us that it’s not the great things that they are calendar. remembered for, but instead a lifetime of invisible and small things - light and inspiration for each of our DEADLINE NEXT ISSUE journeys. December 09, 2018 Phone: +31-74-7074273 cell: +31-6-31072836 [email protected] www.thegrail.org 1 International Activity ILT Face to Face Meeting, Golegã – Portugal As we write this letter, we would like to thank the Grail in Golegã, Portugal, for hosting the ILT face to face meeting followed by the Teams Meeting in which 35 participants gathered to work together for a week. It is with deep gratitude that we thank all Portuguese Grail members who worked hard to make this meeting possible and all of the preparation and work of each participant. A few updates from the ILT face to face meeting: We would like to draw your attention to a few calendar updates, changes and additions: • Network Forum planned for late February/early March 2019 • 2019 IC Meeting in Kisekibaha, Tanzania from July 3 to July 14 • 2020 IC Meeting in July to launch the 2021 ILT election process • 2021 IGA side by side with the Big Meeting (100th Anniversary of the Grail) in Brazil We thank you all for your attention to these calendar changes. -

NOZZOM NEWSLETTER ISSUE #26 - June 2016 Contents 04 NOZZOM NEWSLETTER ISSUE #26 New Leaps

NOZZOM NEWSLETTER ISSUE #26 - June 2016 Contents 04 NOZZOM NEWSLETTER ISSUE #26 New Leaps Chairman Shehab ElNawawi Managing Editor Lara Shawky Agility in Egypt 18 Creative & Art Director Hesham Ezz El-Din Round Up Content & Production Manager 22 Lara Shawky Copywriters Eman Quotb Nancy El-Baroudy Solution Spectrum Photography in Saudi 32 Lara Shawky 38 Africa Special Report Giza Systems, a leading systems integrator in the MEA region, designs and deploys industry-specific technology solutions for asset-intensive industries such as the Telecoms, Utilities, Oil & Gas, Transportation and other market sectors. We help our clients streamline their operations and businesses through our portfolio Corporate Citizen of solutions, managed services, and consultancy practice. Our 56 team of 800 professionals are spread throughout the region with anchor offices in Cairo, Riyadh, Dubai, Nairobi, Dar-es-Salaam and Abuja, allowing us to service an ever-increasing client base in over 40 countries. For more information, please visit http://www. gizasystems.com Nozzom is a biannual publication of Giza Systems. Opinions expressed by contributing writers or material printed from other sources do not necessarily express those of the @ Giza Systems publisher. gizasystems.com and its companies own copyrights for the material contained 62 in this newsletter, including all text, graphics, and photos. The use and/or reproduction by any means of any of the material without the written consent of Giza Systems is strictly prohibited. Copyright @Giza Systems, Egypt, 2016. All rights reserved. Moving… Foreword Welcome to our new issue of Nozzom, where we share with you our events, projects and plans. During the past few months, Giza Systems’ Group of Companies undertook a series of exciting new projects, which will be reported in the coming pages. -

Year 1-2H Curriculum Newsletter to Parents Spring 2 2020 Whole School Topic

Geography Year 1-2H Curriculum In Geography this half term, we will continue to use maps and atlases to name and locate the world’s Newsletter to Parents seven continents and five oceans. Last half term we learned to locate the UK and Europe. Now we’ll be Spring 2 2020 looking at the wider world! We will begin to use basic geographical vocabulary to refer to physical Whole school topic: Diversity and human features in the context of Africa with a particular focus on Kenya. We will use our knowledge of the UK to understand the geographical similarities Class topic: AFRICA and differences of human and physical features between Kenya and the UK too. ART We will be learning all about Tingatinga art. Tingatinga is a painting style widely used across Africa; particularly in Kenya and Tanzania. The style of art is named after the Tanzanian painter Edward Tigatinga. We will first find out about the Edward Tingatinga as an artist and say what we do and don’t like about his style of artwork. We will then learn about primary colours and how to mix secondary colours. We will use black and white paints to add tints and tones, whilst practising using thick and thin brushes to create different effects. Miss Davis and Mrs Roe Science PE We will be studying ‘Living We will be acquiring the things and their habitats’ skills needed to play Dodgeball! Dear parents and carers, We will explore and compare We will be able to use the Our whole school topic is DIVERSITY and our class topic the differences between things terms ‘opponent’ and ‘team- is AFRICA and most of our other subject areas will be that are living, dead, and mate’ and learn how to work based around this topic. -

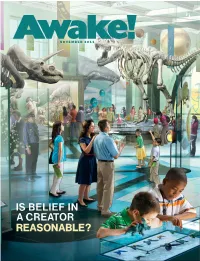

IS BELIEF in a CREATOR REASONABLE? 3 the Most Important Question of All 4 Consider the Evidence 7 Which Approach Is More Reasonable?

!"#2 NOVEMBER 2011 IS BELIEF IN ACREATOR REASONABLE? !"#2 AVERAGE PRINTING 39,913,000 PUBLISHED IN 83 LANGUAGES IS BELIEF IN A CREATOR REASONABLE? 3 The Most Important Question of All 4 Consider the Evidence 7 Which Approach Is More Reasonable? 10 The Bible’s Viewpoint How to Make a Marriage Succeed 12 Climate Summits—Just Talk? 14 Tingatinga—Art That Makes You Smile 16 Was It Designed? The Sea Urchin’s Self-Sharpening Tooth 17 Young People Ask Where Can I Find Good Entertainment? 20 Mexico’s Liquid Ambassador 21 How I Found the Answer to Injustice 24 Dengue—A Growing Menace 26 John Foxe and His Turbulent Times 29 Watching the World 30 For Family Review 32 His Grandfather Had Just Died THE MOST IMPORTANT QUESTION OF ALL OULD there be a more important ques- At Hebrews 11:1, the Bible says: “Faith is “C tion in all of human existence than ‘Is ...theevident demonstration of realities there a God?’” asked geneticist Francis though not beheld.” Another version says: S. Collins. He makes a powerful point. If “Faith . makes us certain of realities we do there is no God, then there is no life beyond not see.” (The New English Bible) To illustrate: the present one, no higher authority on mor- You are walking along a beach when, sud- al issues. denly, you feel the ground quake. Then you The reason some people doubt that God see the water rush out to sea. You recog- exists is because many scientists do not be- nize the significance of these phenomena and lieve in him.