Breaking up Is Hard to Do

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers

Catalog 10 Flyers + Boo-hooray May 2021 22 eldridge boo-hooray.com New york ny Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers Boo-Hooray is proud to present our tenth antiquarian catalog, exploring the ephemeral nature of the flyer. We love marginal scraps of paper that become important artifacts of historical import decades later. In this catalog of flyers, we celebrate phenomenal throwaway pieces of paper in music, art, poetry, film, and activism. Readers will find rare flyers for underground films by Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, and Andy Warhol; incredible early hip-hop flyers designed by Buddy Esquire and others; and punk artifacts of Crass, the Sex Pistols, the Clash, and the underground Austin scene. Also included are scarce protest flyers and examples of mutual aid in the 20th Century, such as a flyer from Angela Davis speaking in Harlem only months after being found not guilty for the kidnapping and murder of a judge, and a remarkably illustrated flyer from a free nursery in the Lower East Side. For over a decade, Boo-Hooray has been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections and look forward to inviting you back to our gallery in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Catalog prepared by Evan Neuhausen, Archivist & Rare Book Cataloger and Daylon Orr, Executive Director & Rare Book Specialist; with Beth Rudig, Director of Archives. Photography by Evan, Beth and Daylon. -

Masculinism, Resistance, and Recognition in Vietnam

NORMA International Journal for Masculinity Studies ISSN: 1890-2138 (Print) 1890-2146 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rnor20 Recognising shadows: masculinism, resistance, and recognition in Vietnam Paul Horton To cite this article: Paul Horton (2019): Recognising shadows: masculinism, resistance, and recognition in Vietnam, NORMA, DOI: 10.1080/18902138.2019.1565166 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/18902138.2019.1565166 © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 11 Jan 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 110 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rnor20 NORMA: INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR MASCULINITY STUDIES https://doi.org/10.1080/18902138.2019.1565166 Recognising shadows: masculinism, resistance, and recognition in Vietnam Paul Horton Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Pride parades, LGBT rights demonstrations, and revisions to the Received 9 July 2017 Marriage and Family Law highlight the extent to which norms and Accepted 12 November 2018 values related to gender, sexuality, marriage, and the family have KEYWORDS recently been challenged in Vietnam. They also illuminate the Vietnam; LGBT; masculinism; gendered power relations being played out in the socio-cultural recognition; power; context of Vietnam, and thus open up for a more in-depth resistance consideration of the ways in which LGBT people have experienced and resisted these relations in everyday life. Drawing on ethnographic fieldwork conducted in Vietnam’s two largest cities, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, in 2012, this article discusses the relations between these power relations, the dominant Vietnamese discourse of masculinity, or masculinism, and the politics of recognition. -

Andy Warhol Shadows Exhibition Brochure.Pdf

Andy Warhol Shadows On Tuesday I hung my painting(s) at the Heiner Friedrich gallery in SoHo. Really it’s presentation. Since the number of panels shown varies according to the available and altered through the abstraction of the silkscreen stencil and the appli- one painting with 83 parts. Each part is 52 inches by 76 inches and they are all sort size of the exhibition space, as does the order of their arrangement, the work in cation of color to reconfigure context and meaning. The repetition of each of the same except for the colors. I called them “Shadows” because they are based total contracts, expands, and recalibrates with each installation. For the work’s famous face drains the image of individuality, so that each becomes a on a photo of a shadow in my office. It’s a silk screen that I mop over with paint. first display, the gallery accommodated 83 panels that were selected and arranged stand-in for non-individuated and depersonalized notions of celebrity.5 The I started working on them a few years ago. I work seven days a week. But I get by Warhol’s assistants in two rooms: the main gallery and an adjacent office. replication of a seemingly abstract gesture (a jagged peak and horizontal the most done on weekends because during the week people keep coming by extension) across the panels of Shadows further minimizes the potential to talk. The all-encompassing (if modular) scale of Shadows simultaneously recalls to ascribe any narrative logic to Warhol’s work. Rather, as he dryly explained, The painting(s) can’t be bought. -

Drone Music from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Drone music From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Drone music Stylistic origins Indian classical music Experimental music[1] Minimalist music[2] 1960s experimental rock[3] Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments,guitars, string instruments, electronic postproduction equipment Mainstream popularity Low, mainly in ambient, metaland electronic music fanbases Fusion genres Drone metal (alias Drone doom) Drone music is a minimalist musical style[2] that emphasizes the use of sustained or repeated sounds, notes, or tone-clusters – called drones. It is typically characterized by lengthy audio programs with relatively slight harmonic variations throughout each piece compared to other musics. La Monte Young, one of its 1960s originators, defined it in 2000 as "the sustained tone branch of minimalism".[4] Drone music[5][6] is also known as drone-based music,[7] drone ambient[8] or ambient drone,[9] dronescape[10] or the modern alias dronology,[11] and often simply as drone. Explorers of drone music since the 1960s have included Theater of Eternal Music (aka The Dream Syndicate: La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Tony Conrad, Angus Maclise, John Cale, et al.), Charlemagne Palestine, Eliane Radigue, Philip Glass, Kraftwerk, Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, Sonic Youth,Band of Susans, The Velvet Underground, Robert Fripp & Brian Eno, Steven Wilson, Phill Niblock, Michael Waller, David First, Kyle Bobby Dunn, Robert Rich, Steve Roach, Earth, Rhys Chatham, Coil, If Thousands, John Cage, Labradford, Lawrence Chandler, Stars of the Lid, Lattice, -

NO RAMBLING ON: the LISTLESS COWBOYS of HORSE Jon Davies

WARHOL pages_BFI 25/06/2013 10:57 Page 108 If Andy Warhol’s queer cinema of the 1960s allowed for a flourishing of newly articulated sexual and gender possibilities, it also fostered a performative dichotomy: those who command the voice and those who do not. Many of his sound films stage a dynamic of stoicism and loquaciousness that produces a complex and compelling web of power and desire. The artist has summed the binary up succinctly: ‘Talk ers are doing something. Beaut ies are being something’ 1 and, as Viva explained about this tendency in reference to Warhol’s 1968 Lonesome Cowboys : ‘Men seem to have trouble doing these nonscript things. It’s a natural 5_ 10 2 for women and fags – they ramble on. But straight men can’t.’ The brilliant writer and progenitor of the Theatre of the Ridiculous Ronald Tavel’s first two films as scenarist for Warhol are paradigmatic in this regard: Screen Test #1 and Screen Test #2 (both 1965). In Screen Test #1 , the performer, Warhol’s then lover Philip Fagan, is completely closed off to Tavel’s attempts at spurring him to act out and to reveal himself. 3 According to Tavel, he was so up-tight. He just crawled into himself, and the more I asked him, the more up-tight he became and less was recorded on film, and, so, I got more personal about touchy things, which became the principle for me for the next six months. 4 When Tavel turned his self-described ‘sadism’ on a true cinematic superstar, however, in Screen Test #2 , the results were extraordinary. -

Warhol, Andy (As Filmmaker) (1928-1987) Andy Warhol

Warhol, Andy (as filmmaker) (1928-1987) Andy Warhol. by David Ehrenstein Image appears under the Creative Commons Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Courtesy Jack Mitchell. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com As a painter Andy Warhol (the name he assumed after moving to New York as a young man) has been compared to everyone from Salvador Dalí to Norman Rockwell. But when it comes to his role as a filmmaker he is generally remembered either for a single film--Sleep (1963)--or for works that he did not actually direct. Born into a blue-collar family in Forest City, Pennsylvania on August 6, 1928, Andrew Warhola, Jr. attended art school at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh. He moved to New York in 1949, where he changed his name to Andy Warhol and became an international icon of Pop Art. Between 1963 and 1967 Warhol turned out a dizzying number and variety of films involving many different collaborators, but after a 1968 attempt on his life, he retired from active duty behind the camera, becoming a producer/ "presenter" of films, almost all of which were written and directed by Paul Morrissey. Morrissey's Flesh (1968), Trash (1970), and Heat (1972) are estimable works. And Bad (1977), the sole opus of Warhol's lover Jed Johnson, is not bad either. But none of these films can compare to the Warhol films that preceded them, particularly My Hustler (1965), an unprecedented slice of urban gay life; Beauty #2 (1965), the best of the films featuring Edie Sedgwick; The Chelsea Girls (1966), the only experimental film to gain widespread theatrical release; and **** (Four Stars) (1967), the 25-hour long culmination of Warhol's career as a filmmaker. -

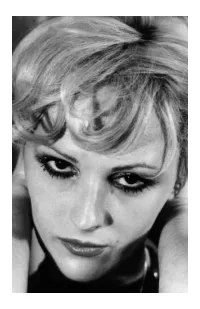

The Raunchy Splendor of Mike Kuchar's Dirty Pictures

MIKE KUCHAR ART The Raunchy Splendor of Mike Kuchar’s Dirty Pictures by JENNIFER KRASINSKI SEPTEMBER 19, 2017 “Blue Eyes” (1980–2000s) MIKE KUCHAR/ANTON KERN GALLERY/GHEBALY GALLERY AS AN ILLUSTRATOR, MY AIM IS TO AMUSE THE EYE AND SPARK IMAGINATION, wrote the great American artist and filmmaker Mike Kuchar in Primal Male, a book of his collected drawings. TO CREATE TITILLATING SCENES THAT REFRESH THE SOUL… AND PUT A BIT MORE “FUN” TO VIEWING PICTURES — and that he has done for over five decades. “Drawings by Mike!” is an exhibition of erotic illustrations at Anton Kern Gallery, one of the fall season’s great feasts for the eye and a welcome homecoming for one of New York’s most treasured prodigal sons. Sympathy for the devil: Mike Kuchar’s “Rescued!” (2017) MIKE KUCHAR/ANTON KERN GALLERY As boys growing up in the Bronx, Mike and his twin brother — the late, equally great film and video artist George (1942–2011) — loved to spend their weekends at the movies, watching everything from newsreels to B films to blockbusters, their young minds roused by all the thrills that Hollywood had to offer: romance, drama, action, science fiction, terror, suspense. As George remembered in their 1997 Reflecons From a Cinemac Cesspool, a memoir-cum–manual for aspiring filmmakers: “On the screen there would always be a wonderful tapestry of big people and they seemed so wild and crazy….e women wantonly lifted up their skirts to adjust garter-belts and men in pin-striped suits appeared from behind shadowed décor to suck and chew on Technicolor lips.” For the Kuchars, as for gay male contemporaries like Andy Warhol and Jack Smith, the movie theater was a temple for erotics both expressed and repressed, projected and appropriated, homo and hetero, all whirled together on the silver screen. -

Elementary Secondary Education Act Title This Seventh Grade Math

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 100 668 88 SE 018 359 PITTS Mathematics 7, Environmental Education Guide. INSTITUTION Project I-C-E, Green Bay, Wis. SPONS AGENCY Bureau of Elementary and Secondary Education (DHPW/OP), Washington, D.C.; Wisconsin State Dept. of Education, Madison. PUB DATE (74] NOT! 44p. EPRS PR/CE MF-$0.75 HC-$1.85 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Conservation Education; *Environmental Education; Grade 7; Instructional Materials; Interdisciplinary Approach; Learning Activities; *Mathematical Applications; Mathematics Education; Natural Resources; Outdoor Education; Science Education; Secondary Education; *Secondary School Mathematics; *Teaching Guides IDENTIFII2RS Computtion; Elementary Secondary Education Act Title III; ESEA Title III; *Project I C E; Proportion ABSTRACT This seventh grade mathematics guide ,s one of a series of guides, K-12, that were developed by teachers to help introduce environmental education into the total curriculum. The guides are supplementary in design, containing a series of episodes (minilessons) that reinforce the relationships between ecology and mathematics. It is the teacher's decision when the episodes may best be integrated into the existing classroom curriculum. The episodes are built around 12 major environmental concepts that form a framework for each grade or subject area, as well as for the entire K-12 program. Although the same concepts are used throughout the K-12 program, emphasis is placed on different aspects of each concept at different grade levels or subject levels. This guide focuses on aspects such as proportion, computation, and percent. The 12 concepts are covered in one of the episodes contained in the guide. Further, each episode offers subject area integration, subject area activities, interdisciplinary activities, cognitive and affective behavioral objectives, and suggested references and resource materials useful to teachers and students. -

Fall 2015 Uchicago Arts Guide

UCHICAGO ARTS FALL 2015 EVENT & EXHIBITION HIGHLIGHTS IN THIS ISSUE The Renaissance Society Centennial UChicago in the Chicago Architecture Biennial CinéVardaExpo.Agnès Varda in Chicago arts.uchicago.edu BerlinFullPage.pdf 1 8/21/15 12:27 PM 2015 Randy L. and Melvin R. BERLIN FAMILY LECTURES CONTENTS 5 Exhibitions & Visual Arts 42 Youth & Family 12 Five Things You (Probably) Didn’t 44 Arts Map Know About the Renaissance Society 46 Info 17 Film 20 CinéVardaExpo.Agnès Varda in Chicago 23 Design & Architecture Icon Key 25 Literature Chicago Architecture Biennial event 28 Multidisciplinary CinéVardaExpo event C M 31 Music UChicago 125th Anniversary event Y 39 Theater, Dance & Performance UChicago student event CM MY AMITAV GHOSH The University of Chicago is a destination where ON THE COVER CY artists, scholars, students, and audiences converge Daniel Buren, Intersecting Axes: A Work In Situ, installation view, CMY T G D and create. Explore our theaters, performance The Renaissance Society, Apr 10–May 4, 1983 K spaces, museums and galleries, academic | arts.uchicago.edu F, H, P A programs, cultural initiatives, and more. Photo credits: (page 5) Attributed to Wassily Kandinsky, Composition, 1914, oil on canvas, Smart Museum of Art, the University of Chicago, Gift of Dolores and Donn Shapiro in honor of Jory Shapiro, 2012.51.; Jessica Stockholder, detail of Rose’s Inclination, 2015, site-specific installation commissioned by the Smart Museum of Art;page ( 6) William G W Butler Yeats (1865–1939), Poems, London: published by T. Fisher Unwin; Boston: Copeland and Day, 1895, promised Gift of Deborah Wachs Barnes, Sharon Wachs Hirsch, Judith Pieprz, and Joel Wachs, AB’92; Justin Kern, Harper Memorial Reading Room, 2015, photo courtesy the artist; page( 7) Gate of Xerxes, Guardian Man-Bulls of the eastern doorway, from Erich F. -

Andy Warhol: When Junkies Ruled the World

Nebula 2.2 , June 2005 Andy Warhol: When Junkies Ruled the World. By Michael Angelo Tata So when the doorbell rang the night before, it was Liza in a hat pulled down so nobody would recognize her, and she said to Halston, “Give me every drug you’ve got.” So he gave her a bottle of coke, a few sticks of marijuana, a Valium, four Quaaludes, and they were all wrapped in a tiny box, and then a little figure in a white hat came up on the stoop and kissed Halston, and it was Marty Scorsese, he’d been hiding around the corner, and then he and Liza went off to have their affair on all the drugs ( Diaries , Tuesday, January 3, 1978). Privileged Intake Of all the creatures who populate and punctuate Warhol’s worlds—drag queens, hustlers, movie stars, First Wives—the drug user and abuser retains a particular access to glamour. Existing along a continuum ranging from the occasional substance dilettante to the hard-core, raging junkie, the consumer of drugs preoccupies Warhol throughout the 60s, 70s and 80s. Their actions and habits fascinate him, his screens become the sacred place where their rituals are projected and packaged. While individual substance abusers fade from the limelight, as in the disappearance of Ondine shortly after the commercial success of The Chelsea Girls , the loss of status suffered by Brigid Polk in the 70s and 80s, or the fatal overdose of exemplary drug fiend Edie Sedgwick, the actual glamour of drugs remains, never giving up its allure. 1 Drugs survive the druggie, who exists merely as a vector for the 1 While Brigid Berlin continues to exert a crucial influence on Warhol’s work in the 70s and 80s—for example, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol , as detailed by Bob Colacello in the chapter “Paris (and Philosophy )”—her street cred. -

Press Release (PDF)

G A G O S I A N G A L L E R Y 14 December 2015 My camera and I, together we have the power to confer or to take away. —Richard Avedon They always say that time changes things, but you actually have to change them yourself. —Andy Warhol Gagosian London is pleased to present the first major exhibition to pair works by Richard Avedon and Andy Warhol. Both artists rose to prominence in postwar America with parallel artistic output that occasionally overlapped. Their most memorable images, produced in response to changing cultural mores, are icons of the twentieth century. Portraiture was a shared focus of both artists, and they made use of repetition and serialization: Avedon through the reproducible medium of photography, and in his group photographs, for which he meticulously positioned, collaged, and reordered images; Warhol in his method of stacked screenprinting, which enabled the consistent reproduction of an image. Avedon’s distinctive gelatin-silver prints and Warhol's boldly colored silkscreens variously depict many of the same recognizable faces, including Marella Agnelli, Bianca Jagger, Jacqueline Kennedy, Marilyn Monroe, and Rudolf Nureyev. Both Avedon and Warhol originated from modest beginnings and had tremendous commercial success working for major magazines in New York, beginning in the 1940s. The 1960s marked artistic turning points for both artists as they moved away increasingly from strictly commercial work towards their mature independent styles. The works in the exhibition, which date from the 1950s through the 1990s, emphasize such common themes as social and political power; the evolving acceptance of cultural differences; the inevitability of mortality; and the glamour and despair of celebrity. -

The Films of Andy Warhol Stillness, Repetition, and the Surface of Things

The Films of Andy Warhol Stillness, Repetition, and the Surface of Things David Gariff National Gallery of Art If you wish for reputation and fame in the world . take every opportunity of advertising yourself. — Oscar Wilde In the future everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes. — attributed to Andy Warhol 1 The Films of Andy Warhol: Stillness, Repetition, and the Surface of Things Andy Warhol’s interest and involvement in film ex- tends back to his childhood days in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Warhol was sickly and frail as a youngster. Illness often kept him bedridden for long periods of time, during which he read movie magazines and followed the lives of Hollywood celebri- ties. He was an avid moviegoer and amassed a large collection of publicity stills of stars given out by local theaters. He also created a movie scrapbook that included a studio portrait of Shirley Temple with the handwritten inscription: “To Andrew Worhola [sic] from Shirley Temple.” By the age of nine, Warhol had received his first camera. Warhol’s interests in cameras, movie projectors, films, the mystery of fame, and the allure of celebrity thus began in his formative years. Many labels attach themselves to Warhol’s work as a filmmaker: documentary, underground, conceptual, experi- mental, improvisational, sexploitation, to name only a few. His film and video output consists of approximately 650 films and 4,000 videos. He made most of his films in the five-year period from 1963 through 1968. These include Sleep (1963), a five- hour-and-twenty-one minute look at a man sleeping; Empire (1964), an eight-hour film of the Empire State Building; Outer and Inner Space (1965), starring Warhol’s muse Edie Sedgwick; and The Chelsea Girls (1966) (codirected by Paul Morrissey), a double-screen film that brought Warhol his greatest com- mercial distribution and success.