Polygamy After Windsor: What's Religion Got to Do with It General Essays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2005 Softball Guide

Media Outlets Table of Contents GENERAL INFORMATION Quick Facts ..................................................................... IFC Media Outlets ..................................................................... 1 Schedule/Travel Itinerary .................................................... 2 Roster ................................................................................. 3 Season Outlook................................................................ 4-5 COACHES AND PLAYER BIOS Head Coach Mona Stevens .............................................. 6-7 Assistant Coaches ................................................................ 7 Player Bios .......................................................................... 8 MEDIA OUTLETS (801 area code) 2004 RECAP 2004 Statistical Leaders ..................................................... 17 NEWSPAPERS KSL-5 (NBC) Phone: 575-5535/5593 2004 Statistics ................................................................... 18 Daily Utah Chronicle 2004 Results/Recap........................................................... 19 Phone: 581-6397 KSTU-13 (FOX) Fax: 581-3299 Phone: 536-1371/1311 THE RIVALS Deseret News KJZZ-14 (Flagship Station) 2004 Opponents ............................................................... 20 Phone: 237-2161 Phone: 537-1414 Fax: 237-2543 HISTORY/RECORDS RADIO Salt Lake Tribune All-Time Records and Honors .......................................... 21 Phone: 257-8900 Hot Ticket-700 (Flagship Ute Head Coaches ........................................................... -

Legislating First Cousin Marriage in the Progressive Era

KISSING COUSINS: LEGISLATING FIRST COUSIN MARRIAGE IN THE PROGRESSIVE ERA Lori Jean Wilson Consanguineous or close-kin marriages are older than history itself. They appear in the religious texts and civil records of the earliest known societies, both nomadic and sedentary. Examples of historical cousin-marriages abound. However, one should not assume that consanguineous partnerships are archaic or products of a bygone era. In fact, Dr. Alan H. Bittles, a geneticist who has studied the history of cousin-marriage legislation, reported to the New York Times in 2009 that first-cousin marriages alone account for 10 percent of global marriages.1 As of 2010, twenty-six states in the United States permit first cousin marriage. Despite this legal acceptance, the stigma attached to first-cousin marriage persists. Prior to the mid- nineteenth century, however, the American public showed little distaste toward the practice of first cousin marriage. A shift in scientific opinion emerged in the mid-nineteenth century and had anthropologists questioning whether the custom had a place in western civilization or if it represented a throwback to barbarism. The significant shift in public opinion however, occurred during the Progressive Era as the discussion centered on genetics and eugenics. The American public vigorously debated whether such unions were harmful or beneficial to the children produced by first cousin unions. The public also debated what role individual states, through legislation, should take in restricting the practice of consanguineous marriages. While divergent opinions emerged regarding the effects of first cousin marriage, the creation of healthy children and a better, stronger future generation of Americans remained the primary goal of Americans on both sides of the debate. -

Marriage Outlaws: Regulating Polygamy in America

Faucon_jci (Do Not Delete) 1/6/2015 3:10 PM Marriage Outlaws: Regulating Polygamy in America CASEY E. FAUCON* Polygamist families in America live as outlaws on the margins of society. While the insular groups living in and around Utah are recognized by mainstream society, Muslim polygamists (including African‐American polygamists) living primarily along the East Coast are much less familiar. Despite the positive social justifications that support polygamous marriage recognition, the practice remains taboo in the eyes of the law. Second and third polygamous wives are left without any legal recognition or protection. Some legal scholars argue that states should recognize and regulate polygamous marriage, specifically by borrowing from business entity models to draft default rules that strive for equal bargaining power and contract‐based, negotiated rights. Any regulatory proposal, however, must both fashion rules that are applicable to an American legal system, and attract religious polygamists to regulation by focusing on the religious impetus and social concerns behind polygamous marriage practices. This Article sets out a substantive and procedural process to regulate religious polygamous marriages. This proposal addresses concerns about equality and also reflects the religious and as‐practiced realities of polygamy in the United States. INTRODUCTION Up to 150,000 polygamists live in the United States as outlaws on the margins of society.1 Although every state prohibits and criminalizes polygamy,2 Copyright © 2014 by Casey E. Faucon. * Casey E. Faucon is the 2013‐2015 William H. Hastie Fellow at the University of Wisconsin Law School. J.D./D.C.L., LSU Paul M. Hebert School of Law. -

Nancy Daniels President and General Manager, TLC

Nancy Daniels President and General Manager, TLC As President and General Manager of TLC, Daniels leads the company’s flagship female focused channel, a global brand available in more than 90 million homes nationally and 271 million households around the world. Daniels oversees all aspects of the network’s programming, production, development, multiplatform, communications and marketing in the US. Daniels is the most senior female content executive at Discovery Communications, which reaches 3 billion cumulative viewers across pay-TV and free-to-air platforms in more than 220 countries. Based in the company’s Los Angeles office, she’s held this position since September 2013. Amid ever more fierce competition for audience, Daniels has maintained TLC’s reign as a top 10 network for women with long running hit series Sister Wives, The Little Couple, My 600-lb Life, Return to Amish, Kate Plus 8, 90 Day Fiancé as well as new series 90 Day Fiancé: Happily Ever After?, Long Lost Family, The Spouse House and OutDaughtered. Of the 19 returning series in 2017 to-date, 17 are up or on par versus their previous season. In addition, TLC continues to show strong growth finishing out third quarter 2017 up 19% in primetime versus year ago and ranked as the #6 ad-supported cable network among W25-54. This year, TLC made a major announcement under the helm of Daniels, bringing back original home design series TRADING SPACES after ten years, with Paige Davis returning as host. As one of the most beloved TLC shows that started the home makeover craze, viewers will watch as families and neighbors hand over the keys to their home and let the renovation fun begin. -

Sister Wives: a New Beginning for United States Polygamist Families on the Eve of Polygamy Prosecution

Volume 19 Issue 1 Article 7 2012 Sister Wives: A New Beginning for United States Polygamist Families on the Eve of Polygamy Prosecution Katilin R. McGinnis Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Katilin R. McGinnis, Sister Wives: A New Beginning for United States Polygamist Families on the Eve of Polygamy Prosecution, 19 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 249 (2012). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol19/iss1/7 This Casenote is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. McGinnis: Sister Wives: A New Beginning for United States Polygamist Famili SISTER WIVES: A NEW BEGINNING FOR UNITED STATES POLYGAMIST FAMILIES ON THE EVE OF POLYGAMY PROSECUTION? I. INTRODUCTION "Love should be multiplied, not divided," a statement uttered by one of today's most infamous, and candid, polygamists, Kody Brown, during the opening credits of each episode of The Learning Channel's ("TLC") hit reality television show, Sister Wives.' Kody Brown, a fundamentalist Mormon who lives in Nevada, openly prac- tices polygamy or "plural marriage" and is married in the religious sense to four women: Meri, Janelle, Christine, and Robyn. 2 The TLC website describes the show's purpose as an attempt by the Brown family to show the rest of the country (or at least those view- ers tuning into their show) how they function as a "normal" family despite the fact that their lifestyle is shunned by the rest of society.3 It is fair to say, however, that the rest of the country not only shuns their lifestyle but also criminalizes it with laws upheld against consti- tutional challenge by the Supreme Court in Reynolds v. -

Why the Relationships Between Wives in Polygynous Marriages Deserve Legal Recognition

Indiana Journal of Law and Social Equality Volume 5 Issue 2 Article 6 Spring 5-9-2017 Empowering Sister Wives: Why the Relationships Between Wives in Polygynous Marriages Deserve Legal Recognition Stephanie Halsted Indiana University Maurer School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijlse Part of the Law Commons Publication Citation Stephanie Halsted, Empowering Sister Wives: Why the Relationships Between Wives in Polygynous Marriages Deserve Legal Recognition, 5 Ind. J.L. & Soc. Equality 355 (2017). This Student Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Journal of Law and Social Equality by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Empowering Sister Wives: Why the Relationships Between Wives in Polygynous Marriages Deserve Legal Recognition Stephanie Halsted* INTRODUCTION The legal arguments disfavoring the legalization of polygamous marriages often invoke the notion of an assumed negative impact that polygynous marriages have on the “victims” of the institution: the wives and children.1 The women in such marriages are framed as powerless chumps who are brainwashed into a patriarchal cult of female subjugation where they function no more than as homemaking robots for their promiscuous husbands.2 While there has been debate in courtrooms and legal scholarship over the legal recognition -

The Modern Opinions Regarding Polygamy of Married Men and Women in Dakar

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2013 The oM dern Opinions Regarding Polygamy of Married Men and Women in Dakar Hannah Fried-Tanzer SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons Recommended Citation Fried-Tanzer, Hannah, "The odeM rn Opinions Regarding Polygamy of Married Men and Women in Dakar" (2013). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1680. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1680 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 The Modern Opinions Regarding Polygamy of Married Men and Women in Dakar Fried-Tanzer, Hannah Academic Director: Diallo, Souleye Project Adviser: Gaye, Rokhaya George Washington University French and Anthropology Senegal, Dakar Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Senegal: National Identity and the Arts Program SIT Study Abroad, Fall 2013 2 Table of Contents Abstract 2 Introduction and Historical Context 3 Methodology 9 Findings/Interviews 11 Monogamy 11 Polygamy 13 Results and Analysis 21 Misgivings 24 Challenges 25 Conclusion 25 Works Cited 27 Interviews Cited 29 Appendix A: Questionnaire 30 Appendix B: Time Log 31 3 Abstract Polygamy is the practice in which a man takes multiple wives. While it is no longer legal in certain countries, it is still allowed both legally and religiously in Senegal, and is still practiced today. -

FOR Why Were You Rescued and Brought to Wildcare Eastern Sierra

The Inyo Register TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 11, 2020 7 MAN ON THE STREET Why were you rescued and brought to Wildcare Eastern Sierra for help? By Wildcare Eastern Sierra “A man rescued my “I was pulled from my “I was hunting near “I found an opening into “I saw a dead rabbit on “A few friends and I nest when he saw mom nest by a bird with a some buildings, chasing a big building where the side of the highway. were flying near Church had been killed. When sharp beak. I wiggled a mouse, and I fell in a someone kept leaving I flew down to take it and Fowler, looking for he took us to Wildcare, and it dropped me to pan full of motor oil. A some yummy snacks. away, but as I lifted up, food. I got into some it was time for me to the ground. My tummy person found me and One night they set a a truck ran into me. My kind of opening and break out of my egg. was bleeding. A person took me to Wildcare. A trap and I was caught. wing was injured. I could couldn’t get out. A per- Most of my brothers and found me and took me lot of Dawn baths will Wildcare came and, run but I couldn’t fly. A son saw me and went to sisters were hatching to her house where she make sure my feathers since I wasn’t hurt, sheriff and a volunteer the Police Department. too. I’m learning how to fed me and took care are clean.” they took me to a good from Wildcare caught They came and picked find food.” of me. -

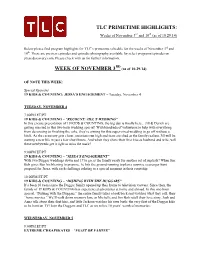

TLC PRIMETIME HIGHLIGHTS: Weeks of November 3Rd and 10Th (As of 10.29.14)

TLC PRIMETIME HIGHLIGHTS: Weeks of November 3rd and 10th (as of 10.29.14) Below please find program highlights for TLC’s primetime schedule for the weeks of November 3rd and 10th. There are preview episodes and episodic photography available for select programs/episodes on press.discovery.com. Please check with us for further information. RD WEEK OF NOVEMBER 3 (as of 10.29.14) OF NOTE THIS WEEK: Special Episodes 19 KIDS & COUNTING: JESSA’S ENGAGEMENT – Tuesday, November 4 TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 4 7:00PM ET/PT 19 KIDS & COUNTING – “RECOUNT: JILL’S WEDDING” In this encore presentation of 19 KIDS & COUNTING, the big day is finally here... Jill & Derick are getting married in this two-hour wedding special! With hundreds of volunteers to help with everything from decorating to finishing the cake, they’re aiming for this super-sized wedding to go off without a hitch. As the ceremony gets closer, emotions run high and tears are shed as the family realizes Jill will be starting a new life in just a few short hours. And when they share their first kiss as husband and wife, will these newlyweds get it right or miss the mark? 9:00PM ET/PT 19 KIDS & COUNTING – “JESSA’S ENGAGEMENT” With two Duggar weddings down and 17 to go, is the family ready for another set of nuptials? When Jim Bob gives Ben his blessing to propose, he hits the ground running to plan a surprise scavenger hunt proposal for Jessa, with each challenge relating to a special moment in their courtship. 10:00PM ET/PT 19 KIDS & COUNTING – “DISHING WITH THE DUGGARS” It’s been 10 years since the Duggar family opened up their home to television viewers. -

Marriage and Divorce in Islamic and Mormon Polygamy: a Legal Comparison

Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies Volume 1 Number 1 Inaugural Issue Article 6 2009 Marriage and Divorce in Islamic and Mormon Polygamy: A Legal Comparison Nate Olsen University of Utah Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/imwjournal Recommended Citation Olsen, Nate "Marriage and Divorce in Islamic and Mormon Polygamy: A Legal Comparison." Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies 1, no. 1 (2009). https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/imwjournal/vol1/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Olsen: Islamic/Mormon Polygamy 87 Nate Olsen Nate Olsen is a J.D. candidate at the S. J. Quinney College of Law, where he serves on the 2009–10 Board of Editors of the Utah Law Review. He graduated magna cum laude from Brigham Young University with a B.A. in Spanish and a minor in history. 88 IMW Journal of Religious Studies Vol. 1:1 Nate Olsen Marriage and Divorce in Islamic and Mormon Polygamy: A Legal Comparison This paper compares how Islam and Mormonism crafted the legal frame- work of polygamy in an attempt to afford women important protections against its inherent inequality. Islam and Mormonism provided these safeguards by regulating how parties entered polygamy and by allowing women to initiate di- vorce. I. INTRODUCTION In the fifth year of the Hijrah, Mohammad received a revelation that ush- ered in the age of Shari’ah, or Islamic holy law: “To thee We sent the Scripture in truth . -

Pooch Perfect Finding Your Roots 47 Meters Down

TUESDAY MORNING APRIL 13, 2021 CHARTER DISH DTV 6 AM 6:30 7 AM 7:30 8 AM 8:30 9 AM 9:30 10 AM 10:30 11 AM 11:30 KAPP (2) 42 35 Good Morning (CC) (N) Good Morning America (CC) (N) Live (CC) (N) The View (CC) Paid Minute (N) KCYU (3) 41 - Rock Park AgDay (CC) Good Day (CC) (N) 25 Words 25 Words Tamron Hall (CC) Maury KNDO (4) 25 23 WakeUpNorthwest (N) Today (CC) (N) Today III (CC) (N) Hoda and Jenna (CC) (N) Wendy Williams (CC) KING (5) - - King 5 News (CC) (N) Today (CC) (N) Today III (CC) (N) Hoda and Jenna (CC) (N) New Day (CC) KIMA (6) 29 29 News (N) News (N) CBS This Morning (CC) (N) Kelly Clarkson (CC) The Price Is Right (CC) Young & Restless (N) KIRO (7) - - KIRO 7 News (CC) (N) CBS This Morning (CC) (N) Let's Make a Deal (CC) The Price Is Right (CC) Young & Restless (N) KYVE (8) 47 47 Jet Go! Arthur (CC) Molly Wild K. 2/2 Hero EleXavier C.George D.Tiger D.Tiger Elinor W Sesame St. PinkaPet KIMA2 (9) 33 - The National Desk (CC) The National Desk (CC) Steve Wilkos Show Steve Wilkos Show Maury Maury KOMO (11) - - KOMO 4 News (CC) (N) Good Morning America (CC) (N) Live (CC) (N) The View (CC) KOMO 4 News (CC) (N) KUNW (18) 2 - Como dice el dicho (CC) Despierta America (CC) Como dice el dicho (CC) TUESDAY AFTERNOON APRIL 13, 2021 CHARTER DISH DTV 12 PM 12:30 1 PM 1:30 2 PM 2:30 3 PM 3:30 4 PM 4:30 5 PM 5:30 KAPP (2) 42 35 You Need to Know (N) General Hospital (CC) The Doctors (CC) Rachael Ray (CC) The Dr. -

Counseling the Polyamorous Client: Implications for Competent Practice

fSuggested APA style reference information can be found at http://www.counseling.org/knowledge-center/vistas Article 50 Counseling the Polyamorous Client: Implications for Competent Practice Adrianne L. Johnson Johnson, Adrianne L., is an Assistant Professor of Clinical Mental Health Counseling at Wright State University. Her experience includes adult outpatient, crisis, college, and rehabilitation counseling. She has presented internationally on a broad range of counseling and counselor education topics, and her research interests include bias and diversity in counseling and counselor education. Abstract The self-reports of polyamorous clients regarding therapeutic experiences raise concerns for the counseling field. Many poly individuals are not receiving quality mental health care or relationship counseling because of valid fears regarding professional bias and condemnation of their lifestyle choices. The unique issues and concerns of polyamorous clients is an emerging interest in the mental health field and counselors have an ethical obligation to understand, explore, and address the unique needs of this population. Introduction The current culture in the United States has historically promoted heterosexual monogamy as the most widely accepted and advocated ethical/moral relationship option available, and clients identifying as polyamorous often practice covertly and with great stress “due to the cultural pressure, social stigmas, or fear of legal ramifications” (Black, 2006, p. 1). Polyamory is a lifestyle in which a person may have more than one romantic relationship with consent and support expressed for this choice by each of the people concerned (Weitzman, 2006, p. 139). Polyamorous people face stigmatization, stereotypes, negative bias, and marginalization in both the mainstream society and in the offices of counseling professionals.