Why the Relationships Between Wives in Polygynous Marriages Deserve Legal Recognition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2005 Softball Guide

Media Outlets Table of Contents GENERAL INFORMATION Quick Facts ..................................................................... IFC Media Outlets ..................................................................... 1 Schedule/Travel Itinerary .................................................... 2 Roster ................................................................................. 3 Season Outlook................................................................ 4-5 COACHES AND PLAYER BIOS Head Coach Mona Stevens .............................................. 6-7 Assistant Coaches ................................................................ 7 Player Bios .......................................................................... 8 MEDIA OUTLETS (801 area code) 2004 RECAP 2004 Statistical Leaders ..................................................... 17 NEWSPAPERS KSL-5 (NBC) Phone: 575-5535/5593 2004 Statistics ................................................................... 18 Daily Utah Chronicle 2004 Results/Recap........................................................... 19 Phone: 581-6397 KSTU-13 (FOX) Fax: 581-3299 Phone: 536-1371/1311 THE RIVALS Deseret News KJZZ-14 (Flagship Station) 2004 Opponents ............................................................... 20 Phone: 237-2161 Phone: 537-1414 Fax: 237-2543 HISTORY/RECORDS RADIO Salt Lake Tribune All-Time Records and Honors .......................................... 21 Phone: 257-8900 Hot Ticket-700 (Flagship Ute Head Coaches ........................................................... -

Nancy Daniels President and General Manager, TLC

Nancy Daniels President and General Manager, TLC As President and General Manager of TLC, Daniels leads the company’s flagship female focused channel, a global brand available in more than 90 million homes nationally and 271 million households around the world. Daniels oversees all aspects of the network’s programming, production, development, multiplatform, communications and marketing in the US. Daniels is the most senior female content executive at Discovery Communications, which reaches 3 billion cumulative viewers across pay-TV and free-to-air platforms in more than 220 countries. Based in the company’s Los Angeles office, she’s held this position since September 2013. Amid ever more fierce competition for audience, Daniels has maintained TLC’s reign as a top 10 network for women with long running hit series Sister Wives, The Little Couple, My 600-lb Life, Return to Amish, Kate Plus 8, 90 Day Fiancé as well as new series 90 Day Fiancé: Happily Ever After?, Long Lost Family, The Spouse House and OutDaughtered. Of the 19 returning series in 2017 to-date, 17 are up or on par versus their previous season. In addition, TLC continues to show strong growth finishing out third quarter 2017 up 19% in primetime versus year ago and ranked as the #6 ad-supported cable network among W25-54. This year, TLC made a major announcement under the helm of Daniels, bringing back original home design series TRADING SPACES after ten years, with Paige Davis returning as host. As one of the most beloved TLC shows that started the home makeover craze, viewers will watch as families and neighbors hand over the keys to their home and let the renovation fun begin. -

Sister Wives: a New Beginning for United States Polygamist Families on the Eve of Polygamy Prosecution

Volume 19 Issue 1 Article 7 2012 Sister Wives: A New Beginning for United States Polygamist Families on the Eve of Polygamy Prosecution Katilin R. McGinnis Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Katilin R. McGinnis, Sister Wives: A New Beginning for United States Polygamist Families on the Eve of Polygamy Prosecution, 19 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 249 (2012). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol19/iss1/7 This Casenote is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. McGinnis: Sister Wives: A New Beginning for United States Polygamist Famili SISTER WIVES: A NEW BEGINNING FOR UNITED STATES POLYGAMIST FAMILIES ON THE EVE OF POLYGAMY PROSECUTION? I. INTRODUCTION "Love should be multiplied, not divided," a statement uttered by one of today's most infamous, and candid, polygamists, Kody Brown, during the opening credits of each episode of The Learning Channel's ("TLC") hit reality television show, Sister Wives.' Kody Brown, a fundamentalist Mormon who lives in Nevada, openly prac- tices polygamy or "plural marriage" and is married in the religious sense to four women: Meri, Janelle, Christine, and Robyn. 2 The TLC website describes the show's purpose as an attempt by the Brown family to show the rest of the country (or at least those view- ers tuning into their show) how they function as a "normal" family despite the fact that their lifestyle is shunned by the rest of society.3 It is fair to say, however, that the rest of the country not only shuns their lifestyle but also criminalizes it with laws upheld against consti- tutional challenge by the Supreme Court in Reynolds v. -

FOR Why Were You Rescued and Brought to Wildcare Eastern Sierra

The Inyo Register TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 11, 2020 7 MAN ON THE STREET Why were you rescued and brought to Wildcare Eastern Sierra for help? By Wildcare Eastern Sierra “A man rescued my “I was pulled from my “I was hunting near “I found an opening into “I saw a dead rabbit on “A few friends and I nest when he saw mom nest by a bird with a some buildings, chasing a big building where the side of the highway. were flying near Church had been killed. When sharp beak. I wiggled a mouse, and I fell in a someone kept leaving I flew down to take it and Fowler, looking for he took us to Wildcare, and it dropped me to pan full of motor oil. A some yummy snacks. away, but as I lifted up, food. I got into some it was time for me to the ground. My tummy person found me and One night they set a a truck ran into me. My kind of opening and break out of my egg. was bleeding. A person took me to Wildcare. A trap and I was caught. wing was injured. I could couldn’t get out. A per- Most of my brothers and found me and took me lot of Dawn baths will Wildcare came and, run but I couldn’t fly. A son saw me and went to sisters were hatching to her house where she make sure my feathers since I wasn’t hurt, sheriff and a volunteer the Police Department. too. I’m learning how to fed me and took care are clean.” they took me to a good from Wildcare caught They came and picked find food.” of me. -

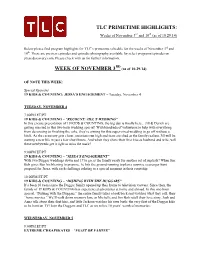

TLC PRIMETIME HIGHLIGHTS: Weeks of November 3Rd and 10Th (As of 10.29.14)

TLC PRIMETIME HIGHLIGHTS: Weeks of November 3rd and 10th (as of 10.29.14) Below please find program highlights for TLC’s primetime schedule for the weeks of November 3rd and 10th. There are preview episodes and episodic photography available for select programs/episodes on press.discovery.com. Please check with us for further information. RD WEEK OF NOVEMBER 3 (as of 10.29.14) OF NOTE THIS WEEK: Special Episodes 19 KIDS & COUNTING: JESSA’S ENGAGEMENT – Tuesday, November 4 TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 4 7:00PM ET/PT 19 KIDS & COUNTING – “RECOUNT: JILL’S WEDDING” In this encore presentation of 19 KIDS & COUNTING, the big day is finally here... Jill & Derick are getting married in this two-hour wedding special! With hundreds of volunteers to help with everything from decorating to finishing the cake, they’re aiming for this super-sized wedding to go off without a hitch. As the ceremony gets closer, emotions run high and tears are shed as the family realizes Jill will be starting a new life in just a few short hours. And when they share their first kiss as husband and wife, will these newlyweds get it right or miss the mark? 9:00PM ET/PT 19 KIDS & COUNTING – “JESSA’S ENGAGEMENT” With two Duggar weddings down and 17 to go, is the family ready for another set of nuptials? When Jim Bob gives Ben his blessing to propose, he hits the ground running to plan a surprise scavenger hunt proposal for Jessa, with each challenge relating to a special moment in their courtship. 10:00PM ET/PT 19 KIDS & COUNTING – “DISHING WITH THE DUGGARS” It’s been 10 years since the Duggar family opened up their home to television viewers. -

Pooch Perfect Finding Your Roots 47 Meters Down

TUESDAY MORNING APRIL 13, 2021 CHARTER DISH DTV 6 AM 6:30 7 AM 7:30 8 AM 8:30 9 AM 9:30 10 AM 10:30 11 AM 11:30 KAPP (2) 42 35 Good Morning (CC) (N) Good Morning America (CC) (N) Live (CC) (N) The View (CC) Paid Minute (N) KCYU (3) 41 - Rock Park AgDay (CC) Good Day (CC) (N) 25 Words 25 Words Tamron Hall (CC) Maury KNDO (4) 25 23 WakeUpNorthwest (N) Today (CC) (N) Today III (CC) (N) Hoda and Jenna (CC) (N) Wendy Williams (CC) KING (5) - - King 5 News (CC) (N) Today (CC) (N) Today III (CC) (N) Hoda and Jenna (CC) (N) New Day (CC) KIMA (6) 29 29 News (N) News (N) CBS This Morning (CC) (N) Kelly Clarkson (CC) The Price Is Right (CC) Young & Restless (N) KIRO (7) - - KIRO 7 News (CC) (N) CBS This Morning (CC) (N) Let's Make a Deal (CC) The Price Is Right (CC) Young & Restless (N) KYVE (8) 47 47 Jet Go! Arthur (CC) Molly Wild K. 2/2 Hero EleXavier C.George D.Tiger D.Tiger Elinor W Sesame St. PinkaPet KIMA2 (9) 33 - The National Desk (CC) The National Desk (CC) Steve Wilkos Show Steve Wilkos Show Maury Maury KOMO (11) - - KOMO 4 News (CC) (N) Good Morning America (CC) (N) Live (CC) (N) The View (CC) KOMO 4 News (CC) (N) KUNW (18) 2 - Como dice el dicho (CC) Despierta America (CC) Como dice el dicho (CC) TUESDAY AFTERNOON APRIL 13, 2021 CHARTER DISH DTV 12 PM 12:30 1 PM 1:30 2 PM 2:30 3 PM 3:30 4 PM 4:30 5 PM 5:30 KAPP (2) 42 35 You Need to Know (N) General Hospital (CC) The Doctors (CC) Rachael Ray (CC) The Dr. -

Brodie: the Woman and Richard S

]ULY-AUGUST /982 VOLUME SEVEN, NUMBER FOUR Publisher/Editor RELIGION 7 BETWEEN HEAVEN AND EARTH: MORMON LA WRENCE FOSTER PEGGY FLETCHER THEOLOGY OF THE FAMILY IN Managing Editor COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE SUSAN STAKER OMAN The Shakers, the Oneida Perfectionists, the Mormons Associate Editor NICOLE HOFFMAN 12 A RESPONSE MARYBETH RAYNES Art Director BRIAN E. BEAN CONTEMPORARY 16 A LIGHT UNTO THE WORLD: ISSUES IN PEGGY FLETCHER MORMON IMAGE MAKING Poetry Editor DENNIS CLARK 24 A LIGHT UNTO THE WORLD: ISSUES IN BRUCE L. CHRISTENSEN MORMON IMAGE MAKING Fiction Editor B.H. Roberts Society lectures on Church MARY MONSON public relations Business Manager RENEE HEPWORTH LITERATURE 26 WE ARE ALL ENLISTED: WAR AS METAPHOR STEPHEN L, TANNER Advertising Should we feel uneasy about the martial ROBIN BARTLETT strain in our religion? CONNIE R. JONES Circulation/Promotion REBECCAH T. HARRIS HISTORY 32 FAWN M. BRODIE: THE WOMAN AND RICHARD S. DEBBIE DUPONT HER HISTORY VAN WAGONER MARK JARDINE A personal look at Mormonism’s JIM HEPWORTH best-known rebel Staff 43 SHEAVES, BUCKLERS, AND THE STATE: RONALD W. WALKER KERRY WILLIAM BATE MORMON LEADERS RESPOND TO GARY HOFFMAN THE DILEMMAS OF WAR JOHN SILLITO Do the Saints owe their loyalty to CHRIS THOMAS conscience, church, or nation? MARK THOMAS FICTION 38 MAKING SURE WARREN EUGENE ICKE Returning from Vietnam HUMOR $6 NEW POLICIES: TRIBUTE TO MANHOOD RICHARD K. CIRCUIT An appreciation for the unique contribution of fathers DEPARTMENTS 2 READERS’ FORUM 5 PARADOXES AND PERPLEXITIES MAR VIN RYTTING 61 LAW OF THE LAND JAY BYBEE 62 THE NOUMENONIST PAUL M. EDWARDS 64 GIVE AND TAKE SUSAN STAKER OMAN ~tlnnl’l ll~’n l~’ The’ (hutch td Iv+us (brim of Lallt.r-dav Manvs~r~pls tot pubh~ahon ~h~uld bu ~ubmHled dupht ah. -

TV Listings FRIDAY, JUNE 26, 2015

TV listings FRIDAY, JUNE 26, 2015 13:15 From Up On Poppy Hill 15:00 Scooby-Doo! Adventures: The Mystery Map! 16:00 Garfield’s Fun Fest 18:00 Vampire Dog 20:00 Hiroku: Defenders Of Gaia 22:00 Scooby-Doo! Adventures: The Mystery Map! 23:30 Garfield’s Fun Fest 00:00 A Family Reunion-PG15 02:00 Vamps-PG15 04:00 Safe-PG15 06:00 Hellboy: Sword Of Storms-PG 08:00 Last Passenger-PG15 10:00 Europa Report-PG15 12:00 Safe-PG15 14:00 The Croods-PG 16:00 Last Passenger-PG15 17:45 Captain Phillips-PG15 20:00 The Internship-PG15 22:15 Maximum Conviction-PG15 01:30 Golfing World 07:00 Golfing World 08:00 World Rugby 08:30 ICC Cricket 360 09:00 Volvo Ocean Race Highlights 10:30 Live Super Rugby 12:30 Live PGA European Tour 15:30 Inside The PGA Tour 16:00 European Tour Weekly 16:30 Live PGA European Tour 22:00 Live PGA Tour 09:00 Golfing World 12:00 World Rugby 12:30 Live NRL Premiership 16:00 NRL Premiership 18:00 Golfing World ON OSN MOVIES HD 19:00 WWE Bottomline THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN 2 20:00 WWE Superstars 21:00 WWE Main Event 16:25 Little People, Big World 12:10 Steven Universe Jones 10:00 Sofia The First 01:15 Loopdidoo 16:50 Little People, Big World 12:35 Regular Show 13:40 Who On Earth Did I Marry? 10:25 Jake’s Buccaneer Blast 01:30 Art Attack 17:15 Something Borrowed, 13:25 Clarence 14:05 Who On Earth Did I Marry? 10:30 Jake And The Never Land 01:55 Henry Hugglemonster Something New 13:50 Uncle Grandpa 14:30 On The Case With Paula Pirates 02:05 Calimero 17:40 Something Borrowed, 14:15 Matt Hatter Chronicles Zahn 10:55 Runaway Shuffle/Surfin’ -

View, and My Wife Shauntel for Their Support in the Creation of This Note

POLYMMIGRATION: IMMIGRATION IMPLICATIONS AND POSSIBILITIES POST BROWN V. BUHMAN Greggary E. Lines* In recent years polygamy has taken center stage on prime-time television and in the nation’s courts. After the Supreme Court’s reexamination of marriage in Obergefell v. Hodges, polygamy was thought to be the next major issue the Court hears regarding the structure and purpose of marriage and family. The Sister Wives case, Brown v. Buhman, may have a broader effect on U.S. policies and laws than merely in the realm of marriage and cohabitation. In fact, it may be a gateway to offering other benefits, such as immigration benefits, to polygamist families. The rationale of Brown challenges the longstanding bars against polygamous immigrants. While the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals dismissed Brown on mootness grounds, subsequent appeals or challenges to anti-polygamy laws could be the beginning of a reexamination of policy and law that can better address the realities of immigration in the globalized age. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 478 I. POLYFACTS ....................................................................................................... 483 A. Forms of Polygamy Around the World ...................................................... 483 B. Modern Polygamy in the United States ...................................................... 487 II. POLYCRIMINALIZATION: THE BAN OF POLYGAMY IN THE UNITED STATES...... 488 A. A History of -

TLC PRIMETIME HIGHLIGHTS: Weeks of January 20Th, 27Th, and Feb

TLC PRIMETIME HIGHLIGHTS: Weeks of January 20th, 27th, and Feb. 3rd (as of 1.30.13) Below please find program highlights for TLC’s primetime schedule for the weeks of January 20th, 27th, and February 3rd. There are preview episodes and episodic photography available for select programs/episodes on press.discovery.com. Please check with us for further information. TLC PRESS CONTACT: Jordyn Linsk: 240-662-2421 [email protected] TH WEEK OF JANUARY 20 (as of 1.21.13) OF NOTE THIS WEEK: Season Finales OUTRAGEOUS 911 (Season 1) – Saturday, January 25 MONDAY, JANUARY 20 9:00PM ET/PT CAKE BOSS – “SICILIAN SAMURAI” This week Buddy finds his inner warrior to create a one-of-a-kind samurai cake for the 50th Anniversary of a New York martial arts school. Also, Buddy makes a patriotic cake for the new Mayor of Jersey City. And when things get stressful at the bakery, Buddy turns the decorating room into a giant sumo-wrestling ring! 10:00PM ET/PT BAKERY BOSS – “DREW’S PASTRY PLACE” With the financial support of his family, Drew opened an Italian pastry shop in Houston. But business has been tough and Buddy discovers the bakery is now $600,000 in the hole. Despite the pressures of not wanting to fail, Drew refuses to expand the menu. Buddy has a plan to heal the family rifts and revamp the menu, but will Drew finally be willing to listen? TUESDAY, JANUARY 21 9:00PM ET/PT MY 600-LB. LIFE – “PENNY’S STORY” Bedridden for four years, 46-year old Penny knows that her weight may kill her if drastic actions aren’t taken. -

Våren 2017 På TLC

Outdaughtered. 2016-12-12 15:04 CET Våren 2017 på TLC Outdaughtered: The Busby quints Premiär lördag 7 januari 19.00 Familjen Busby, från League City, Texas, är en familj som sticker ut i statistiken. När det blev känt att paret väntade femlingar, alla flickor, blev de en viral hit med en blogg som lästes av 100 miljoner människor. Deras familj var historisk redan innan barnen fötts: de första kvinnliga femlingarna i USA någonsin och de tredje i hela världen. I april 2015 kom femlingarna till världen och välkomnades av mamma Danielle, pappa Adam och storasyster Blayke. Nu får vi följa femlingarna och deras föräldrar och storasyster i vardagen – en vardag som bland annat innebär drygt 40 flaskor med ersättning om dagen och 420 blöjbyten i veckan. Både säsong 1 och 2 sänds under våren. David Tutera: CELEBrations Premiär måndag 30 januari 22.00 David Tutera är en erfaren bröllopsplanerare som har bestämt sig för att börja planera alla möjliga typer av fester. Kunderna är kändisar som vill ha hjälp att göra festen till något alldeles speciellt. I den här serien följer vi David när han planerar olika typer av festligheter tillsammans med bland andra Jersey Shore's JWoww, artisten Lil' Kim och hemmafruar från Real Housewives-serierna. Kunderna kan vara krävande – och ibland helt omöjliga. Vilket gör att det ganska ofta inte går som det var tänkt! Dessutom blir det en ny säsong av Say yes to the dress Canada, en uppföljning på 90 days to wed samt mer Don’t tell the bride senare i vår. Favoriter tillbaka på TLC Säsong 8 av Masterchef Australia startar söndag 15 januari 20.00 Domartrion Gary, George och Matt är tillbaka i åttonde säsongen av den prisvinnande matlagningstävlingen Masterchef Australia redan i mitten av januari. -

06 01-21-14 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday,January 21, 2014 Monday Evening January 27, 2014 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC The Bachelor Castle Local Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline WEEK OF FRIDAY, JAN. 24 THROUGH THURSDAY, JAN. 30 KBSH/CBS How I Met 2 Broke G Mike Mom Intelligence Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson KSNK/NBC Hollywood Game Night Hollywood Game Night The Blacklist Local Tonight Show w/Leno J. Fallon FOX The Following The Following Local Cable Channels A&E Duck D. Duck D. Bad Ink Bad Ink Mayne Mayne Mayne Mayne Duck D. Duck D. AMC The Green Mile Twister ANIM Finding Bigfoot Gator Boys Beaver Beaver Finding Bigfoot Gator Boys CNN Anderson Cooper 360 Piers Morgan Live AC 360 Later E. B. OutFront Piers Morgan Live DISC Fast N' Loud Fast N' Loud Rods N' Wheels Fast N' Loud Rods N' Wheels DISN Good Luck Let It Shine Good Luck Austin ANT Farm Good Luck Good Luck E! E! News Fashion Police Kardashian Chelsea E! News Norton TV ESPN College Basketball College Basketball SportsCenter SportsCenter ESPN2 Wm. Basketball Wm. Basketball Olbermann Olbermann FAM Switched at Birth The Fosters The Fosters The 700 Club Switched at Birth FX Frnds-Benefits Archer Chozen Archer Chozen Chozen Archer HGTV Love It or List It Love It or List It Hunters Hunt Intl Love It or List It Love It or List It HIST Pawn Pawn Swamp People Pawn Pawn Pawn Pawn Pawn Pawn LIFE Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Listings: MTV Teen Wolf Teen Wolf Teen Wolf Teen Wolf Teen Wolf I, Robot NICK Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Friends Friends Friends SCI Lost Girl Being Human Bitten Lost Girl Being Human For your SPIKE Law Abiding Citizen Alpha Dog TBS Fam.