Reference and Informational Genres

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy, Theory, and Literature

STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS PHILOSOPHY, THEORY, AND LITERATURE 20% DISCOUNT NEW & FORTHCOMING ON ALL TITLES 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Redwood Press .............................2 Square One: First-Order Questions in the Humanities ................... 2-3 Currencies: New Thinking for Financial Times ...............3-4 Post*45 ..........................................5-7 Philosophy and Social Theory ..........................7-10 Meridian: Crossing Aesthetics ............10-12 Cultural Memory in the Present ......................... 12-14 Literature and Literary Studies .................... 14-18 This Atom Bomb in Me Ordinary Unhappiness Shakesplish The Long Public Life of a History in Financial Times Asian and Asian Lindsey A. Freeman The Therapeutic Fiction of How We Read Short Private Poem Amin Samman American Literature .................19 David Foster Wallace Shakespeare’s Language Reading and Remembering This Atom Bomb in Me traces what Critical theorists of economy tend Thomas Wyatt Digital Publishing Initiative ....19 it felt like to grow up suffused with Jon Baskin Paula Blank to understand the history of market American nuclear culture in and In recent years, the American fiction Shakespeare may have written in Peter Murphy society as a succession of distinct around the atomic city of Oak Ridge, writer David Foster Wallace has Elizabethan English, but when Thomas Wyatt didn’t publish “They stages. This vision of history rests on ORDERING Tennessee. As a secret city during been treated as a symbol, an icon, we read him, we can’t help but Flee from Me.” It was written in a a chronological conception of time Use code S19PHIL to receive a the Manhattan Project, Oak Ridge and even a film character. Ordinary understand his words, metaphors, notebook, maybe abroad, maybe whereby each present slips into the 20% discount on all books listed enriched the uranium that powered Unhappiness returns us to the reason and syntax in relation to our own. -

Strategic Stories: an Analysis of the Profile Genre Amy Jessee Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2009 Strategic Stories: An Analysis of the Profile Genre Amy Jessee Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Jessee, Amy, "Strategic Stories: An Analysis of the Profile Genre" (2009). All Theses. 550. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/550 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STRATEGIC STORIES: AN ANALYSIS OF THE PROFILE GENRE A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Professional Communication by Amy Katherine Jessee May 2009 Accepted by: Dr. Sean Williams, Committee Chair Dr. Susan Hilligoss Dr. Mihaela Vorvoreanu ABSTRACT This case study examined the form and function of student profiles published on five university websites. This emergent form of the profile stems from antecedents in journalism, biography, and art, while adapting to a new rhetorical situation: the marketization of university discourse. Through this theoretical framework, universities market their products and services to their consumer, the student, and stories of current students realize and reveal a shift in discursive practices that changes the way we view universities. A genre analysis of 15 profiles demonstrates how their visual patterns and obligatory move structure create a cohesive narrative and two characters. They strategically show features of a successful student fitting with the institutional values and sketch an outline of the institutional identity. -

Satirical News Detection and Analysis Using Attention Mechanism and Linguistic Features

Satirical News Detection and Analysis using Attention Mechanism and Linguistic Features Fan Yang and Arjun Mukherjee Eduard Gragut Department of Computer Science Computer and Information Sciences University of Houston Temple University fyang11,arjun @uh.edu [email protected] { } Abstract ... “Kids these days are done with stories where things happen,” said CBC consultant and world's oldest child Satirical news is considered to be enter- psychologist Obadiah Sugarman. “We'll finally be giv- tainment, but it is potentially deceptive ing them the stiff Victorian morality that I assume is in and harmful. Despite the embedded genre vogue. Not to mention, doing a period piece is a great way to make sure white people are adequately repre- in the article, not everyone can recognize sented on television.” the satirical cues and therefore believe the ... news as true news. We observe that satiri- Table 1: A paragraph of satirical news cal cues are often reflected in certain para- graphs rather than the whole document. Existing works only consider document- gardless of the ridiculous content1. It is also con- level features to detect the satire, which cluded that fake news is similar to satirical news could be limited. We consider paragraph- via a thorough comparison among true news, fake level linguistic features to unveil the satire news, and satirical news (Horne and Adali, 2017). by incorporating neural network and atten- This paper focuses on satirical news detection to tion mechanism. We investigate the differ- ensure the trustworthiness of online news and pre- ence between paragraph-level features and vent the spreading of potential misleading infor- document-level features, and analyze them mation. -

Themes in Dialogue Worksheet

Dialogue is one of the most dynamic elements of novel-writing. It reveals character, deepens conflict, and shares information. However, did you know that dialogue is also a fantastic way of nurturing a story’s themes? If you closely study what’s being said, you’ll find that the message being delivered is often as memorable as the speaker’s words and emotions. How can you let your story’s themes shine through in your dialogue without making them too obvious? That’s what the Themes In Dialogue Worksheet is for! It includes three activities that will help you determine how well your story’s dialogue reveals literary themes through conversation basics, emotional subtext, and repetition. This worksheet is based on the activities in my DIY MFA article “Developing Themes In Your Stories: Part Four – Dialogue.” Click here to read the article before continuing. Instructions: Print out a copy of this worksheet, and have either a print or electronic version of your WIP available for selecting dialogue excerpts to use in the following activities. 1. Dissect Your Dialogue Using the Four Basics of Conversation Purposeful dialogue consists of four conversation “basics” that can be dissected as follows: a) Topic: What is the subject of the dialogue, or of the chosen excerpt from a longer conversation? b) Details: What questions do the participating characters ask? What information is revealed? c) Opinions: What points do the participating characters make in favor of or against the topic? How do other characters receive those opinions? d) Themes: What high-level concepts emerge from the dialogue? In other words, what are the characters really talking about? Chances are, the first three “basics” will be revealed directly through dialogue. -

Introduction Screenwriting Off the Page

Introduction Screenwriting off the Page The product of the dream factory is not one of the same nature as are the material objects turned out on most assembly lines. For them, uniformity is essential; for the motion picture, originality is important. The conflict between the two qualities is a major problem in Hollywood. hortense powdermaker1 A screenplay writer, screenwriter for short, or scriptwriter or scenarist is a writer who practices the craft of screenwriting, writing screenplays on which mass media such as films, television programs, comics or video games are based. Wikipedia In the documentary Dreams on Spec (2007), filmmaker Daniel J. Snyder tests studio executive Jack Warner’s famous line: “Writers are just sch- mucks with Underwoods.” Snyder seeks to explain, for example, why a writer would take the time to craft an original “spec” script without a mon- etary advance and with only the dimmest of possibilities that it will be bought by a studio or producer. Extending anthropologist Hortense Powdermaker’s 1950s framing of Hollywood in the era of Jack Warner and other classic Hollywood moguls as a “dream factory,” Dreams on Spec pro- files the creative and economic nightmares experienced by contemporary screenwriters hoping to clock in on Hollywood’s assembly line of creative uniformity. There is something to learn about the craft and profession of screenwrit- ing from all the characters in this documentary. One of the interviewees, Dennis Palumbo (My Favorite Year, 1982), addresses the downside of the struggling screenwriter’s life with a healthy dose of pragmatism: “A writ- er’s life and a writer’s struggle can be really hard on relationships, very hard for your mate to understand. -

ELEMENTS of FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms That Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction

Dr. Hallett ELEMENTS OF FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms that Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction” is defined as any imaginative re-creation of life in prose narrative form. All fiction is a falsehood of sorts because it relates events that never actually happened to people (characters) who never existed, at least not in the manner portrayed in the stories. However, fiction writers aim at creating “legitimate untruths,” since they seek to demonstrate meaningful insights into the human condition. Therefore, fiction is “untrue” in the absolute sense, but true in the universal sense. Critical Thinking – analysis of any work of literature – requires a thorough investigation of the “who, where, when, what, why, etc.” of the work. Narrator / Narrative Voice Guiding Question: Who is telling the story? …What is the … Narrative Point of View is the perspective from which the events in the story are observed and recounted. To determine the point of view, identify who is telling the story, that is, the viewer through whose eyes the readers see the action (the narrator). Consider these aspects: A. Pronoun p-o-v: First (I, We)/Second (You)/Third Person narrator (He, She, It, They] B. Narrator’s degree of Omniscience [Full, Limited, Partial, None]* C. Narrator’s degree of Objectivity [Complete, None, Some (Editorial?), Ironic]* D. Narrator’s “Un/Reliability” * The Third Person (therefore, apparently Objective) Totally Omniscient (fly-on-the-wall) Narrator is the classic narrative point of view through which a disembodied narrative voice (not that of a participant in the events) knows everything (omniscient) recounts the events, introduces the characters, reports dialogue and thoughts, and all details. -

Magic Realism As Rewriting Postcolonial Identity: a Study of Rushdie’S Midnight’S Children

Magic Realism as Rewriting Postcolonial Identity 74 SCHOLARS: Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 3, No. 1, February 2021, pp. 74-82 Central Department of English Tribhuvan University [Peer-Reviewed, Open Access, Indexed in NepJOL] Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal Print ISSN: 2773-7829; e-ISSN: 2773-7837 www.cdetu.edu.np/ejournal/ DOI: https://doi.org/10.3126/sjah.v3i1.35376 ____________________________________________Theoretical/Critical Essay Article Magic Realism as Rewriting Postcolonial Identity: A Study of Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children Khum Prasad Sharma Department of English Padma Kanya Multiple Campus, TU, Kathmandu, Nepal Corresponding Author: Khum Prasad Sharma, Email: [email protected] Copyright 2021 © Author/s and the Publisher Abstract Magic realism as a literary narrative mode has been used by different critics and writers in their fictional works. The majority of the magic realist narrative is set in a postcolonial context and written from the perspective of the politically oppressed group. Magic realism, by giving the marginalized and the oppressed a voice, allows them to tell their own story, to reinterpret the established version of history written from the dominant perspective and to create their own version of history. This innovative narrative mode in its opposition of the notion of absolute history emphasizes the possibility of simultaneous existence of many truths at the same time. In this paper, the researcher, in efforts to unfold conditions culturally marginalized, explores the relevance of alternative sense of reality to reinterpret the official version of colonial history in Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children from the perspective of magic realism. As a methodological approach to respond to the fiction text, magic realism endows reinterpretation and reconsideration of the official colonial history in reaffirmation of identity of the culturally marginalized people with diverse voices. -

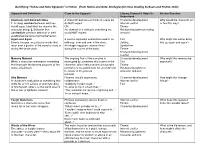

Identifying “Notice and Note Signposts” in Fiction (From Notice and Note: Strategies for Close Reading by Beers and Probst, 2012)

Identifying “Notice and Note Signposts” in Fiction (from Notice and Note: Strategies for Close Reading by Beers and Probst, 2012) Signpost and Definitions Clues to the Signpost Literary Element It Helps Us Anchor Question Understand Contrasts and Contradictions A character behaves or thinks in a way we Character development Why would the character act 1. A sharp contrast between what we do NOT expect. Internal conflict or feel this way? would expect and what we observe the OR Theme character doing. 2. Behavior that An element of a setting is something we Relationship between setting contradicts previous behavior or well- would NOT expect. and plot established patterns (normal behavior). Again and Again A word is repeated, sometimes used in an Plot Why might the author bring Events, images, or particular words that odd way, over and over in the story. Setting this up again and again? recur over a portion of the novel or story or An image reappears several times Symbolism during the whole work. during the course of the book. Theme Character development Conflict Memory Moment The ongoing flow of the narrative is Character development Why might this memory be When a character remembers something interrupted by a memory that comes to the Plot important? that interrupts the forward progress of the character, often taking several paragraphs Theme story; a flashback. (or more) to recount before we are returned Relationship between to events of the present character and plot moment. Aha Moment Phrases usually expressing Character development How might this change A character’s realization of something that suddenness: Internal conflict things? shifts his or her actions or understanding “Suddenly I understood...” Plot of him/herself, others, or the world around “It came to me in a flash that...” him or her (a lightbulb moment). -

Magical Realism and Latin America Maria Eugenia B

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library 5-2003 Magical Realism and Latin America Maria Eugenia B. Rave Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Latin American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Rave, Maria Eugenia B., "Magical Realism and Latin America" (2003). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 481. http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/481 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. MAGICAL REALISM AND LATIN AMERICA BY Maria Eugenia B. Rave A.S. University of Maine, 1991 B.A. University of Maine, 1995 B.S. University of Maine, 1995 A MASTER PROJECT Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in Liberal Studies) The Graduate School The University of Maine May, 2003 Advisory Committee: Kathleen March, Professor of Spanish, Advisor Michael H. Lewis, Professor of Art James Troiano, Professor of Spanish Owen F. Smith, Associate Professor of Art Copyright 2003 Maria Eugenia Rave MAGICAL REALISM AND LATIN AMERICA By Maria Eugenia Rave Master Project Advisor: Professor Kathleen March An Abstract of the Master Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in Liberal Studies) May, 2003 This work is an attempt to present a brief and simple view, both written and illustrated, concerning the controversial concept of Magical Realism for non-specialists. This study analyzes Magical Realism as a form of literary expression and artistic style by some Latin American authors and two artists. -

Film & TV Screenwriting (SCWR)

Film & TV Screenwriting (SCWR) 1 SCWR 122 | SCRIPT TO SCREEN (FORMERLY DC 224) | 4 quarter hours FILM & TV SCREENWRITING (Undergraduate) This analytical course examines the screenplay's evolution to the screen (SCWR) from a writer's perspective. Students will read feature length scripts of varying genres and then perform a critical analysis and comparison of the SCWR 100 | INTRODUCTION TO SCREENWRITING (FORMERLY DC 201) | text to the final produced versions of the films. Storytelling conventions 4 quarter hours such as structure, character development, theme, and the creation of (Undergraduate) tension will be used to uncover alterations and how these adjustments This course is an introduction to and overview of the elements of theme, ultimately impacted the film's reception. plot, character, and dialogue in dramatic writing for cinema. Emphasis is SCWR 123 | ADAPTATION: THE CINEMATIC RECRAFTING OF MEANING placed on telling a story in terms of action and the reality of characters. (FORMERLY DC 235) | 4 quarter hours The difference between the literary and visual medium is explored (Undergraduate) through individual writing projects and group analysis. Films and scenes This course explores contemporary cinematic adaptations of literature examined in this class will reflect creators and characters from a wide and how recent re-workings in film open viewers up to critical analysis range of diverse backgrounds and intersectional identities. Development of the cultural practices surrounding the promotion and reception of of a synopsis and treatment for a short theatrical screen play: theme, plot, these narratives. What issues have an impact upon the borrowing character, mise-en-scene and utilization of cinematic elements. -

Screenplay Format Guide

Screenplay Format Guide Format-wise, anything that makes your script stand out is unwise. This may seem counterintuitive. Anything you do to make your screenplay distinctive is good, right? Depart from the traditional format, though, and you risk having your script prejudged as amateurish. A truly conscientious reader will overlook such superficial matters and focus on content. However, if your work looks unprofessional, it may not be taken seriously. To ensure your script gets a fair read, follow these formatting guidelines: It isn’t necessary to file a copyright with the Library of Congress. Your script is automatically protected under common law. However, it’s a good idea to register it, either with an online service, such as the National Creative Registry (protectrite.com), or with the Writers Guild. This being said, the Industry tends to view registration and copyright notices as the marks of a paranoid amateur. You would be wise to leave them off your script. Use a plain cover. White or pastel card stock, not leatherette. Avoid using screw posts or plastic-comb binding. Bind your script with sturdy, brass fasteners, such as those made by ACCOÒ. The ones Staples sells are too flimsy. Readers hate it when a script falls apart in their hands. You can order professional-quality script supplies online from WritersStore.com. Although scripts are printed on three-hole-punched paper, there’s an unwritten rule that speculative scripts are bound with two fasteners, not three. Why this tends to be common practice is unclear. Perhaps it’s because submissions often get copied by the studio’s story department, and it’s easier (and cheaper) if there are only two brads. -

Satire and Irony in Emily Naralla's Novel Flight Against Time

International Journal of Language and Literature June 2015, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 198-207 ISSN: 2334-234X (Print), 2334-2358 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2015. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijll.v3n1a25 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.15640/ijll.v3n1a25 Satire and Irony in Emily Na ṣralla's Novel Flight against Time Yaseen Kittani 1 & Fayyad Haibi 2 Abstract This study attempts to reveal the role of Satire in the dialectic of Staying and Emigration in Emily Na ṣralla's novel, Flight against Time, (Na ṣralla 2001) which was created out of the Lebanese Civil War in three main axes: language, character and event, in addition to the literary techniques that Satire generally adopts, and which fit with the three previous axes to achieve the satiric indication and effect. Being an 'anatomical' writing tool that is bitterly critical, Satire managed to 'determine' this dialectic to the advantage of the first side (Staying) due to its psychologically defensive feature that enables the character to determine this conflict in the darkest and most complicated circumstances. Undoubtedly, Satire reinforces the indication of Staying in extremely unusual conditions of the Lebanese Civil War and its indirect 'call' that the text tries to convey to all the Lebanese, with no exception, to hold fast to their homeland and defend it, specifically at the time of ordeal. Satire shows also the clear tendency towards the first side (Staying) of this dialectic in the three axes. Language contributed also to Ra ḍwān's expression of this desire directly and indirectly.