Satire and Irony in Emily Naralla's Novel Flight Against Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy, Theory, and Literature

STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS PHILOSOPHY, THEORY, AND LITERATURE 20% DISCOUNT NEW & FORTHCOMING ON ALL TITLES 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Redwood Press .............................2 Square One: First-Order Questions in the Humanities ................... 2-3 Currencies: New Thinking for Financial Times ...............3-4 Post*45 ..........................................5-7 Philosophy and Social Theory ..........................7-10 Meridian: Crossing Aesthetics ............10-12 Cultural Memory in the Present ......................... 12-14 Literature and Literary Studies .................... 14-18 This Atom Bomb in Me Ordinary Unhappiness Shakesplish The Long Public Life of a History in Financial Times Asian and Asian Lindsey A. Freeman The Therapeutic Fiction of How We Read Short Private Poem Amin Samman American Literature .................19 David Foster Wallace Shakespeare’s Language Reading and Remembering This Atom Bomb in Me traces what Critical theorists of economy tend Thomas Wyatt Digital Publishing Initiative ....19 it felt like to grow up suffused with Jon Baskin Paula Blank to understand the history of market American nuclear culture in and In recent years, the American fiction Shakespeare may have written in Peter Murphy society as a succession of distinct around the atomic city of Oak Ridge, writer David Foster Wallace has Elizabethan English, but when Thomas Wyatt didn’t publish “They stages. This vision of history rests on ORDERING Tennessee. As a secret city during been treated as a symbol, an icon, we read him, we can’t help but Flee from Me.” It was written in a a chronological conception of time Use code S19PHIL to receive a the Manhattan Project, Oak Ridge and even a film character. Ordinary understand his words, metaphors, notebook, maybe abroad, maybe whereby each present slips into the 20% discount on all books listed enriched the uranium that powered Unhappiness returns us to the reason and syntax in relation to our own. -

Strategic Stories: an Analysis of the Profile Genre Amy Jessee Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2009 Strategic Stories: An Analysis of the Profile Genre Amy Jessee Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Jessee, Amy, "Strategic Stories: An Analysis of the Profile Genre" (2009). All Theses. 550. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/550 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STRATEGIC STORIES: AN ANALYSIS OF THE PROFILE GENRE A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Professional Communication by Amy Katherine Jessee May 2009 Accepted by: Dr. Sean Williams, Committee Chair Dr. Susan Hilligoss Dr. Mihaela Vorvoreanu ABSTRACT This case study examined the form and function of student profiles published on five university websites. This emergent form of the profile stems from antecedents in journalism, biography, and art, while adapting to a new rhetorical situation: the marketization of university discourse. Through this theoretical framework, universities market their products and services to their consumer, the student, and stories of current students realize and reveal a shift in discursive practices that changes the way we view universities. A genre analysis of 15 profiles demonstrates how their visual patterns and obligatory move structure create a cohesive narrative and two characters. They strategically show features of a successful student fitting with the institutional values and sketch an outline of the institutional identity. -

Satirical News Detection and Analysis Using Attention Mechanism and Linguistic Features

Satirical News Detection and Analysis using Attention Mechanism and Linguistic Features Fan Yang and Arjun Mukherjee Eduard Gragut Department of Computer Science Computer and Information Sciences University of Houston Temple University fyang11,arjun @uh.edu [email protected] { } Abstract ... “Kids these days are done with stories where things happen,” said CBC consultant and world's oldest child Satirical news is considered to be enter- psychologist Obadiah Sugarman. “We'll finally be giv- tainment, but it is potentially deceptive ing them the stiff Victorian morality that I assume is in and harmful. Despite the embedded genre vogue. Not to mention, doing a period piece is a great way to make sure white people are adequately repre- in the article, not everyone can recognize sented on television.” the satirical cues and therefore believe the ... news as true news. We observe that satiri- Table 1: A paragraph of satirical news cal cues are often reflected in certain para- graphs rather than the whole document. Existing works only consider document- gardless of the ridiculous content1. It is also con- level features to detect the satire, which cluded that fake news is similar to satirical news could be limited. We consider paragraph- via a thorough comparison among true news, fake level linguistic features to unveil the satire news, and satirical news (Horne and Adali, 2017). by incorporating neural network and atten- This paper focuses on satirical news detection to tion mechanism. We investigate the differ- ensure the trustworthiness of online news and pre- ence between paragraph-level features and vent the spreading of potential misleading infor- document-level features, and analyze them mation. -

Themes in Dialogue Worksheet

Dialogue is one of the most dynamic elements of novel-writing. It reveals character, deepens conflict, and shares information. However, did you know that dialogue is also a fantastic way of nurturing a story’s themes? If you closely study what’s being said, you’ll find that the message being delivered is often as memorable as the speaker’s words and emotions. How can you let your story’s themes shine through in your dialogue without making them too obvious? That’s what the Themes In Dialogue Worksheet is for! It includes three activities that will help you determine how well your story’s dialogue reveals literary themes through conversation basics, emotional subtext, and repetition. This worksheet is based on the activities in my DIY MFA article “Developing Themes In Your Stories: Part Four – Dialogue.” Click here to read the article before continuing. Instructions: Print out a copy of this worksheet, and have either a print or electronic version of your WIP available for selecting dialogue excerpts to use in the following activities. 1. Dissect Your Dialogue Using the Four Basics of Conversation Purposeful dialogue consists of four conversation “basics” that can be dissected as follows: a) Topic: What is the subject of the dialogue, or of the chosen excerpt from a longer conversation? b) Details: What questions do the participating characters ask? What information is revealed? c) Opinions: What points do the participating characters make in favor of or against the topic? How do other characters receive those opinions? d) Themes: What high-level concepts emerge from the dialogue? In other words, what are the characters really talking about? Chances are, the first three “basics” will be revealed directly through dialogue. -

Introduction Screenwriting Off the Page

Introduction Screenwriting off the Page The product of the dream factory is not one of the same nature as are the material objects turned out on most assembly lines. For them, uniformity is essential; for the motion picture, originality is important. The conflict between the two qualities is a major problem in Hollywood. hortense powdermaker1 A screenplay writer, screenwriter for short, or scriptwriter or scenarist is a writer who practices the craft of screenwriting, writing screenplays on which mass media such as films, television programs, comics or video games are based. Wikipedia In the documentary Dreams on Spec (2007), filmmaker Daniel J. Snyder tests studio executive Jack Warner’s famous line: “Writers are just sch- mucks with Underwoods.” Snyder seeks to explain, for example, why a writer would take the time to craft an original “spec” script without a mon- etary advance and with only the dimmest of possibilities that it will be bought by a studio or producer. Extending anthropologist Hortense Powdermaker’s 1950s framing of Hollywood in the era of Jack Warner and other classic Hollywood moguls as a “dream factory,” Dreams on Spec pro- files the creative and economic nightmares experienced by contemporary screenwriters hoping to clock in on Hollywood’s assembly line of creative uniformity. There is something to learn about the craft and profession of screenwrit- ing from all the characters in this documentary. One of the interviewees, Dennis Palumbo (My Favorite Year, 1982), addresses the downside of the struggling screenwriter’s life with a healthy dose of pragmatism: “A writ- er’s life and a writer’s struggle can be really hard on relationships, very hard for your mate to understand. -

ELEMENTS of FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms That Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction

Dr. Hallett ELEMENTS OF FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms that Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction” is defined as any imaginative re-creation of life in prose narrative form. All fiction is a falsehood of sorts because it relates events that never actually happened to people (characters) who never existed, at least not in the manner portrayed in the stories. However, fiction writers aim at creating “legitimate untruths,” since they seek to demonstrate meaningful insights into the human condition. Therefore, fiction is “untrue” in the absolute sense, but true in the universal sense. Critical Thinking – analysis of any work of literature – requires a thorough investigation of the “who, where, when, what, why, etc.” of the work. Narrator / Narrative Voice Guiding Question: Who is telling the story? …What is the … Narrative Point of View is the perspective from which the events in the story are observed and recounted. To determine the point of view, identify who is telling the story, that is, the viewer through whose eyes the readers see the action (the narrator). Consider these aspects: A. Pronoun p-o-v: First (I, We)/Second (You)/Third Person narrator (He, She, It, They] B. Narrator’s degree of Omniscience [Full, Limited, Partial, None]* C. Narrator’s degree of Objectivity [Complete, None, Some (Editorial?), Ironic]* D. Narrator’s “Un/Reliability” * The Third Person (therefore, apparently Objective) Totally Omniscient (fly-on-the-wall) Narrator is the classic narrative point of view through which a disembodied narrative voice (not that of a participant in the events) knows everything (omniscient) recounts the events, introduces the characters, reports dialogue and thoughts, and all details. -

VAOIG-15-04673-333.Pdf

Veterans Health Administration Review of the Implementation of the Veterans Choice Program OFFICE OF AUDITS AND EVALUATIONS VA Office of Inspector General January 30, 2017 15-04673-333 ACRONYMS CBO Chief Business Office FY Fiscal Year NVC Non-VA Care OIG Office of Inspector General PC3 Patient-Centered Community Care TPA Third-Party Administrator VA Department of Veterans Affairs VACAA Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 VCL Veterans Choice List VHA Veterans Health Administration VISN Veterans Integrated Service Network To report suspected wrongdoing in VA programs and operations, contact the VA OIG Hotline: Website: www.va.gov/oig/hotline Email: [email protected] Telephone: 1-800-488-8244 Executive Summary Why We Did This Review The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Inspector General (OIG) conducted this review at the request of U.S. Senator Johnny Isakson, Chairman of the Senate Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, who expressed concerns about the implementation of the Veterans Choice Program (Choice) and, more specifically, about the barriers facing veterans trying to access it. Thus, our review focused on determining whether veterans were experiencing barriers accessing Choice during its first year of implementation, taking into account that this program, as noted by the Under Secretary for Health in his comments attached to this report, has evolved since that time. We will continue our oversight of Choice in FY 2017 and our assessment of the efficacy of VA’s actions to improve the program’s overall effectiveness; as well, we will seek to identify significant program risks delivering these vital health car e services. -

Magic Realism As Rewriting Postcolonial Identity: a Study of Rushdie’S Midnight’S Children

Magic Realism as Rewriting Postcolonial Identity 74 SCHOLARS: Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 3, No. 1, February 2021, pp. 74-82 Central Department of English Tribhuvan University [Peer-Reviewed, Open Access, Indexed in NepJOL] Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal Print ISSN: 2773-7829; e-ISSN: 2773-7837 www.cdetu.edu.np/ejournal/ DOI: https://doi.org/10.3126/sjah.v3i1.35376 ____________________________________________Theoretical/Critical Essay Article Magic Realism as Rewriting Postcolonial Identity: A Study of Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children Khum Prasad Sharma Department of English Padma Kanya Multiple Campus, TU, Kathmandu, Nepal Corresponding Author: Khum Prasad Sharma, Email: [email protected] Copyright 2021 © Author/s and the Publisher Abstract Magic realism as a literary narrative mode has been used by different critics and writers in their fictional works. The majority of the magic realist narrative is set in a postcolonial context and written from the perspective of the politically oppressed group. Magic realism, by giving the marginalized and the oppressed a voice, allows them to tell their own story, to reinterpret the established version of history written from the dominant perspective and to create their own version of history. This innovative narrative mode in its opposition of the notion of absolute history emphasizes the possibility of simultaneous existence of many truths at the same time. In this paper, the researcher, in efforts to unfold conditions culturally marginalized, explores the relevance of alternative sense of reality to reinterpret the official version of colonial history in Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children from the perspective of magic realism. As a methodological approach to respond to the fiction text, magic realism endows reinterpretation and reconsideration of the official colonial history in reaffirmation of identity of the culturally marginalized people with diverse voices. -

Teaching Immigration with the Immigrant Stories Project LESSON PLANS

Teaching Immigration with the Immigrant Stories Project LESSON PLANS 1 Acknowledgments The Immigration History Research Center and The Advocates for Human Rights would like to thank the many people who contributed to these lesson plans. Lead Editor: Madeline Lohman Contributors: Elizabeth Venditto, Erika Lee, and Saengmany Ratsabout Design: Emily Farell and Brittany Lynk Volunteers and Interns: Biftu Bussa, Halimat Alawode, Hannah Mangen, Josefina Abdullah, Kristi Herman Hill, and Meredith Rambo. Archival Assistance and Photo Permissions: Daniel Necas A special thank you to the Immigration History Research Center Archives for permitting the reproduction of several archival photos. The lessons would not have been possible without the generous support of a Joan Aldous Diversity Grant from the University of Minnesota’s College of Liberal Arts. Immigrant Stories is a project of the Immigration History Research Center at the University of Minnesota. This work has been made possible through generous funding from the Digital Public Library of America Digital Hubs Pilot Project, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Humanities. About the Immigration History Research Center Founded in 1965, the University of Minnesota's Immigration History Research Center (IHRC) aims to transform how we understand immigration in the past and present. Along with its partner, the IHRC Archives, it is North America's oldest and largest interdisciplinary research center and archives devoted to preserving and understanding immigrant and refugee life. The IHRC promotes interdisciplinary research on migration, race, and ethnicity in the United States and the world. It connects U.S. immigration history research to contemporary immigrant and refugee communities through its Immigrant Stories project. -

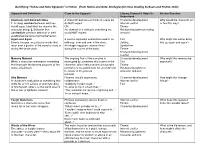

Identifying “Notice and Note Signposts” in Fiction (From Notice and Note: Strategies for Close Reading by Beers and Probst, 2012)

Identifying “Notice and Note Signposts” in Fiction (from Notice and Note: Strategies for Close Reading by Beers and Probst, 2012) Signpost and Definitions Clues to the Signpost Literary Element It Helps Us Anchor Question Understand Contrasts and Contradictions A character behaves or thinks in a way we Character development Why would the character act 1. A sharp contrast between what we do NOT expect. Internal conflict or feel this way? would expect and what we observe the OR Theme character doing. 2. Behavior that An element of a setting is something we Relationship between setting contradicts previous behavior or well- would NOT expect. and plot established patterns (normal behavior). Again and Again A word is repeated, sometimes used in an Plot Why might the author bring Events, images, or particular words that odd way, over and over in the story. Setting this up again and again? recur over a portion of the novel or story or An image reappears several times Symbolism during the whole work. during the course of the book. Theme Character development Conflict Memory Moment The ongoing flow of the narrative is Character development Why might this memory be When a character remembers something interrupted by a memory that comes to the Plot important? that interrupts the forward progress of the character, often taking several paragraphs Theme story; a flashback. (or more) to recount before we are returned Relationship between to events of the present character and plot moment. Aha Moment Phrases usually expressing Character development How might this change A character’s realization of something that suddenness: Internal conflict things? shifts his or her actions or understanding “Suddenly I understood...” Plot of him/herself, others, or the world around “It came to me in a flash that...” him or her (a lightbulb moment). -

The Choice of Law Against Terrorism

The Choice of Law Against Terrorism Mary Ellen O’Connell* On December 25, 2009, a 23-year-old Nigerian, Umar Farouk Abdulmuttalab, took Northwest Airlines Flight 253 from Amsterdam to Detroit, Michigan. Shortly before landing, he allegedly attempted to set off an explosive device. Abdulmuttalab was immediately arrested by police and within a few days was charged by U.S. federal prosecutors with six terrorism-related criminal counts.1 By early January 2010, Senators Joseph Lieberman and Susan Collins, among others, were calling for Abdulmuttalab to be charged as an enemy combatant under the law of armed conflict rather than as a criminal suspect.2 Those critical of the criminal charges generally expressed the view that as a combatant, Abdulmuttalab could be interrogated without the protections provided to a criminal suspect during questioning, especially the right to have a lawyer present.3 Attorney General Eric Holder said that he had considered charging Abdulmuttalab under the law of armed conflict but decided to follow past precedent and policy and charge him under anti-terrorism laws.4 A similar debate was already underway regarding Khalid Sheik Mohammed, the alleged mastermind of the 9/11 attacks. Khalid Sheik Mohammed was originally captured in Pakistan, far from any on-going hostilities. He was subsequently held in secret CIA prisons, where he was waterboarded 183 times, then transferred to the prison at the U.S. Naval base at Guantánamo Bay.5 Attorney General Eric Holder announced that Khalid Sheik Mohammed would be tried in a civilian court on criminal charges of terrorism, but politicians of both major U.S. -

Testimony of SOPHIA COPE Staff Attorney/Ron Plesser Fellow, Center for Democracy & Technology

Testimony of SOPHIA COPE Staff Attorney/Ron Plesser Fellow, Center for Democracy & Technology Before the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, Subcommittee on Oversight of Government Management, the Federal Workforce, and the District of Columbia On “The Impact of Implementation: A Review of the REAL ID Act and the Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative” Tuesday, April 29, 2008 Chairman Akaka, Ranking Member Voinovich, and Members of the Subcommittee: On behalf of the Center for Democracy & Technology,1 I am honored to have been asked to testify before the Subcommittee on the personal privacy and security risks of “vicinity” radio- frequency identification (RFID) technology in travel documents issued in compliance with the Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative (WHTI), specifically the State Department’s passport card and the state-issued “enhanced driver’s license” (EDL). Because this hearing also focuses on REAL ID, I attach as an Appendix CDT’s REAL ID memo from February 1, 2008, analyzing the personal privacy and security risks of the REAL ID Act and the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) final regulations, and proposing legislative options for Congress.2 However, my written testimony below focuses on WHTI, as will my oral testimony. INTRODUCTION From warrantless electronic spying, to expanded DHS funding of closed circuit television (CCTV) video camera surveillance systems without privacy standards, to numerous data breaches at federal agencies, the federal government does not have a good track record of protecting personal privacy. The use of insecure vicinity RFID technology in border crossing identification documents is no exception: With no proven benefit to the nation’s security, the Executive Branch has chosen a technology that jeopardizes privacy.