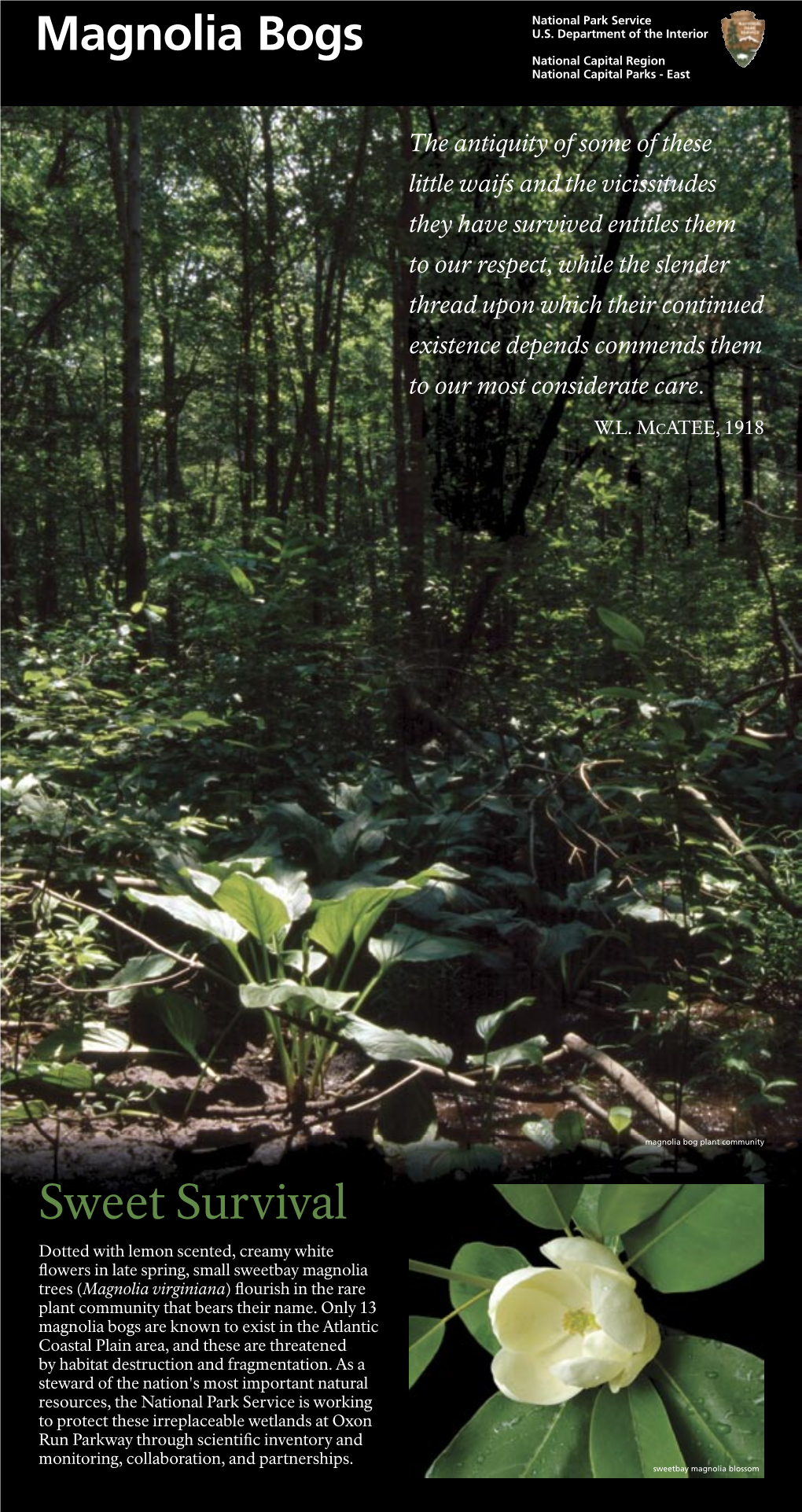

Magnolia Bogs Sweet Survival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States National Museum Bulletin 282

Cl>lAat;i<,<:>';i^;}Oit3Cl <a f^.S^ iVi^ 5' i ''*«0£Mi»«33'**^ SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION MUSEUM O F NATURAL HISTORY I NotUTus albater, new species, a female paratype, 63 mm. in standard length; UMMZ 102781, Missouri. (Courtesy Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan.) UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM BULLETIN 282 A Revision of the Catfish Genus Noturus Rafinesque^ With an Analysis of Higher Groups in the Ictaluridae WILLIAM RALPH TAYLOR Associate Curator, Division of Fishes SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS CITY OF WASHINGTON 1969 IV Publications of the United States National Museum The scientific publications of the United States National Museum include two series, Proceedings of the United States National Museum and United States National Museum Bulletin. In these series are published original articles and monographs dealing with the collections and work of the Museum and setting forth newly acquired facts in the fields of anthropology, biology, geology, history, and technology. Copies of each publication are distributed to libraries and scientific organizations and to specialists and others interested in the various subjects. The Proceedings, begun in 1878, are intended for the publication, in separate form, of shorter papers. These are gathered in volumes, octavo in size, with the publication date of each paper recorded in the table of contents of the volume. In the Bulletin series, the first of which was issued in 1875, appear longer, separate publications consisting of monographs (occasionally in several parts) and volumes in which are collected works on related subjects. Bulletins are either octavo or quarto in size, depending on the needs of the presentation. Since 1902, papers relating to the botanical collections of the Museum have been published in the Bulletin series under the heading Contributions from the United States National Herbarium. -

MONTGOMERY COUNTY COMPREHENSIVE WATER SUPPLY and SEWERAGE SYSTEMS PLAN 2017 - 2026 PLAN: County Executive Draft – March 2017

MONTGOMERY COUNTY COMPREHENSIVE WATER SUPPLY AND SEWERAGE SYSTEMS PLAN 2017 - 2026 PLAN: County Executive Draft – March 2017 CHAPTER 4: SEWERAGE SYSTEMS Table of Contents Table of Figures: ............................................................................................................................... 4-3 Table of Tables: ................................................................................................................................ 4-4 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND: ......................................................................................... 4-5 I. THE WASHINGTON SUBURBAN SANITARY DISTRICT: ..................................................... 4-10 I.A. Government Responsibilities: ......................................................................................... 4-11 I.B. Programs and Policies: ................................................................................................... 4-11 I.B.1. Facility Planning, Project Development and Project Approval Processes: ................. 4-11 I.B.2. Wastewater Flow Analysis: ........................................................................................ 4-12 I.B.3. Sanitary Sewer Overflows: ........................................................................................ 4-17 I.B.4. Sewer Sizing Policies: ............................................................................................... 4-23 I.B.5. Pressure Sewer Systems: ........................................................................................ -

DC Flood Insurance Study

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA WASHINGTON, D.C. REVISED: SEPTEMBER 27, 2010 Federal Emergency Management Agency FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 110001V000A NOTICE TO FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY USERS Communities participating in the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) have established repositories of flood hazard data for floodplain management and flood insurance purposes. This Flood Insurance Study (FIS) report may not contain all data available within the Community Map Repository. Please contact the Community Map Repository for any additional data. Selected Flood Insurance Rate Map (FIRM) panels for this community contain information that was previously shown separately on the corresponding Flood Boundary and Floodway Map panels (e.g., floodways and cross sections). In addition, former flood insurance risk zone designations have been changed as follows. Old Zone(s) New Zone A1 – A30 AE V1 – V30 VE B X C X The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) may revise and republish part or all of this FIS report at any time. In addition, FEMA may revise part of this FIS report by the Letter of Map Revision process, which does not involve republication or redistribution of the FIS report. Therefore, users should consult with community officials and check the Community Map Repository to obtain the most current FIS report components. Initial FIS Effective Date: November 15, 1985 Revised FIS Date: September 27, 2010 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... -

District of Columbia Washington, D.C

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA WASHINGTON, D.C. REVISED: SEPTEMBER 27, 2010 Federal Emergency Management Agency FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 110001V000A NOTICE TO FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY USERS Communities participating in the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) have established repositories of flood hazard data for floodplain management and flood insurance purposes. This Flood Insurance Study (FIS) report may not contain all data available within the Community Map Repository. Please contact the Community Map Repository for any additional data. Selected Flood Insurance Rate Map (FIRM) panels for this community contain information that was previously shown separately on the corresponding Flood Boundary and Floodway Map panels (e.g., floodways and cross sections). In addition, former flood insurance risk zone designations have been changed as follows. Old Zone(s) New Zone A1 – A30 AE V1 – V30 VE B X C X The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) may revise and republish part or all of this FIS report at any time. In addition, FEMA may revise part of this FIS report by the Letter of Map Revision process, which does not involve republication or redistribution of the FIS report. Therefore, users should consult with community officials and check the Community Map Repository to obtain the most current FIS report components. Initial FIS Effective Date: November 15, 1985 Revised FIS Date: September 27, 2010 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... -

1 Class 6 Outline Water Class I. Recap of Acid Rain Issues And

Class 6 Outline Water Class I. Recap of Acid Rain Issues and Transition to Water Pollution. A. What is acid rain? B. How i s it formed? SO2 emissions from coal burning power plants. C. Why is it a problem? Critters and plants that live in water may be harmed. D. How do we measure whether water is affected by acid rain? We measure its pH. II. Experiment: Measuring the pH of water. A. pH ranges. Scale from 0 -14. 7 is neutral. 0 -6 is acidic. 8 -14 is basic. B. Place 3 cups in front of students. Put tap water in each cup . C. Take piece of red and blue paper. Place in any one of the three cups. See what happens. D. Place lemon juice or vinegar in one of the cups. Keep track of which one. Then place blue paper in the cup where the vinegar was inserted. What happened? Chan ged the pH. Made it more acidic. That ’s why paper changed from blue to red. E. Place baking soda in one of the other 2 cups, not the same cup that help the baking soda. Place piece of the red paper in the cup. What happened? Change pH. This time mad e it more basic. 1. Now what is the actual pH of the water? Pass out the pH paper (orangish, tan). 2. Dip pH paper in the cup with no additives. What is the pH on the scale? 3. Dip another piece of pH paper in the cup with the acid. What is the pH on the scale? 4. -

2018 Prince George's County Tax Sale Listings

2018 Prince George’s County Tax Sale Listings 06 0488320 12 1339142 BATCH ONE 4005 LEISURE DR LL 4005 LEISURE DR 6178 OXON HILL PRO 6210 THOMPSON NOTICE OF PUBLIC TAX SALE OF REAL ESTATE 18 2013506 TEMPLE HILLS 20748 17,197.00 SQ FT & LN OXON HILL 20745 22,691.00 SQ FT IN PRINCE GEORGE’S COUNTY, MARYLAND 1002 58TH AVE LLC 1002 58TH AVE CAPI- IMPS LOT 27 BLK 1 SUB GORDONS COR- & IMPS PAR 252 GRD C4 MAP 096 VA- TOL HEIGHTS 20743 3,125.00 SQ FT & IMPS NER ASSESSED FULL CASH VALUE $346,900 CANT LOT ASSESSED FULL CASH VALUE INTERNET-BASED TAX SALE LOT 19 BLK A SUB FAIRMOUNT HEIGHTS TAXES $6,302.38 $223,533 TAXES $4,134.66 MONDAY, MAY 14, 2018 ASSESSED FULL CASH VALUE $87,400 TAX- ES $2,146.44 18 2095248 12 1354893 414 CARMODY HILLS 414 CARMODY A Tax Sale does not automatically convey title to a purchaser; there are legal 6178 OXON HILL PRO 6178 OXON HILL 05 0411454 HILLS DR CAPITOL HEIGHTS 20743 5,000.00 procedures that must be satisfied before becoming the owner of an auctioned RD OXON HILL 20745 1.08 ACRES & IMPS 10114 S CAMPUS WAY 4101 DANVILLE SQ FT & IMPS BLK N SUB CARMODY PAR 253 GRD C4 MAP 096 ASSESSED FULL property. The current owner may redeem by paying the taxes owed. Until the HILLS S HALF LOT 8 L ASSESSED FULL time a deed is issued to the Tax Sale purchaser, the current owner maintains RD BRANDYWINE 20613 21,780.00 SQ FT CASH VALUE $1,838,900 TAXES $520.49 CASH VALUE $142,900 TAXES $2,878.93 ownership of the property. -

DDOT Budget Hearing Testimony

WABA Trails Testimony June 10, 2021 Chairperson Cheh and Members of the Council, Thank you for the opportunity to speak to you today. My name is Ursula Sandstrom. In my job, I work for the Washington Area Bicyclist Association, WABA, as the Outreach Manager though I am here in my personal capacity to share my perspective. These last six years, I have managed WABA’s trails outreach & support program portfolio, which includes the DC Trail Ranger program, and supporting and training 911 on trails. The current budget proposal includes some fantastic, necessary trail investments, making low-stress, off-street, multi-use trails in DC safer to get to and be on. Notably funded are the vital connections between the Anacostia River Trail and Marvin Gaye Trail via Nannie Helen Burroughs Ave NE (identified in the budget in “Anacostia Riverwalk Trail- Neighborhood Access”), and the Arboretum Bridge connections. Additionally the funding for the rehabilitation of Suitland Parkway Trail is necessary as this project is long overdue and the current trail is dangerous. Looking at the overall budget, there is not a clear plan for maintaining all of the current and upcoming trails in a State of Good Repair. The DC Council created the DC Trail Ranger program in 2013 to encourage more residents to use our trails, support trail users, and protect infrastructure investments through timely maintenance. WABA and DDOT Urban Forestry have grown the program into a comprehensive trails maintenance and outreach program, providing the daily service vegetation clearing, trash removal and inspections necessary for navigable corridors. Since 2013, the District has added 8.5 miles of new trail and a lot more people are using DC’s trails, including an 81% increase in Anacostia River Trail use from 2019 to 2020 alone. -

Potomac River Watershed December 31, 2014

Watershed Existing Condition Report for the Potomac River Watershed December 31, 2014 RUSHERN L. BAKER, III COUNTPreparedY EXECUTIV for:E Prince George’s County, Maryland Department of the Environment Stormwater Management Division Prepared by: 10306 Eaton Place, Suite 340 Fairfax, VA 22030 COVER PHOTO CREDITS: 1. M-NCPPC _Cassi Hayden 8. M-NCPPC _Cassi Hayden 2. M-NCPPC _Cassi Hayden 9. M-NCPPC _Cassi Hayden 3. M-NCPPC _Cassi Hayden 10. M-NCPPC _Cassi Hayden 4. M-NCPPC _Cassi Hayden 11. M-NCPPC _Cassi Hayden 5. M-NCPPC _Cassi Hayden 12. M-NCPPC _Cassi Hayden 6. M-NCPPC _Cassi Hayden 13. M-NCPPC _Cassi Hayden 7. M-NCPPC _Cassi Hayden Potomac River Watershed Existing Conditions Report Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations ................................................................................................... iv 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose of Report and Restoration Planning ............................................................................... 1 1.2 Impaired Water Bodies and TMDLs .............................................................................................. 3 1.2.1 Water Quality Standards ..................................................................................................... 4 1.2.2 Problem Identification and Basis for Listing ........................................................................ 5 1.2.3 TMDL Identified Sources ................................................................................................... -

Connections to Neighboring Jurisdictions Map M

Map M Connections to Neighboring Jurisdictions August 2018 21 23 20 24 25 18 19 17 41 39 26 38 16 46 15 27 14 13 28 37 11 10 9 8 7 45 6 44 5 4 3 35 2 1 30 43 31 36 32 Jurisdiction Links Trails Desire Lines Metro Stations Water Existing (9) Primary, Existing Primary (24) Blue Line Institution Desire Line; Planned; Proposed (38) Primary, Planned Secondary (8) Orange Line Parks Secondary, Existing Green Line Area Outside of the Metropolitan District Boundary Secondary, Planned Park Service Areas Park Road, Existing 0 1 2 County Boundary Miles 2-42 Strategic Trails Plan 2018 Appendix: Connectivity to Neighboring Jurisdictions Prince Neighbor Neighbor ID No. Location George’s Co. Notes Jurisdiction Status Status 43 Wilson Bridge Alexandria Existing Existing 25 MD 198 Anne Arundel Proposed Unknown State Hwy Bridge to be 26 WB&A Trail Anne Arundel Existing Existing constructed 27 MD 3 Anne Arundel Proposed Unknown State Hwy Governors Bridge 28 Anne Arundel Existing Unknown Temporarily closed Rd Pennsylvania Ave/ 30 Anne Arundel Proposed Unknown State Hwy MD 4 Chesapeake Beach 31 Anne Arundel Proposed Unknown Environmental Rail Trail Railroad Crossing at Link dependent upon 32 Charles Proposed Unknown Mattawoman Creek railroad abandonment District of DC plans trail link to S 1 Oxon Run Trail Link Existing Planned Columbia Capitol St Trail District of 2 Oxon Run Trail Proposed Unknown Bridge Needed Columbia Oxon Run Trail @ S District of 3 Planned Planned Capitol St Columbia District of 4 Mississippi Ave SE Proposed Planned Environmental Columbia -

Model Selection and Justification Technical Memorandum

Technical Memorandum Model Selection and Justification Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................1 2. Purpose ....................................................................................................................................................1 3. Technical Approach................................................................................................................................ 2 4. Results and Discussion .........................................................................................................................15 Analysis References .................................................................................................................................................. …17 Attachments .................................................................................................................................................. 19 Comprehensive Baseline Comprehensive – , 2014 , December 22 December Consolidated TMDL Implementation Plan Implementation TMDL Consolidated Technical Memorandum: Model Selection and Justification List of Tables Table 1: Modeling Approach used in Mainstem Waterbodies for MS4 Areas ............................................... 4 Table 2: Modeling Approach used in Tributary Waterbodies for MS4 Areas ................................................ 4 Table 3: Modeling Approach used in Other Waterbodies for MS4 Areas ..................................................... -

Rock Creek Park Geologic Resources Inventory Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Rock Creek Park Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2009/146 THTHISIS PAPAGE:GE: Rapids Bridge (built in 1934) over Rock Creek. Rocky streamstreamss aarre a hahalllmarklmark of tthehe PiPiedmontedmont Province, part of the metamorphosed core of the Appalachian Mountains. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Divivisision,on, HiHiststorioricc AmeriAmeri-- can Engineering Record, HAER DC,WASH,569-1. ON THE COVER: Boulder Bridge also spans Rock Creek. Built in 1902, it is an early examplele of rustic architecture in NPS infrastructure. Although the stones were collected outside of the park, they are typical of the weathered cobbles found within Rock Creek Park—eroded remanants of the core of the Appa- lachian Mountains. NPS Photo. Rock Creek Park Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2009/146 Geologic Resources Division Natural Resource Program Center P.O. Box 25287 Denver, Colorado 80225 December 2009 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Denver, Colorado The Natural Resource Publication series addresses natural resource topics that are of interest and applicability to a broad readership in the National Park Service and to others in the management of natural resources, including the scientific community, the public, and the NPS conservation and environmental constituencies. Manuscripts are peer-reviewed to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and is designed and published in a professional manner. Natural Resource Reports are the designated medium for disseminating high priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. -

Nutrient Cause of Impairments Listed by Waterbody Name

Nutrient Cause of Impairments Listed by Waterbody Name (data pull as of 5/28/2008) PARENT_CAUSE STATE WATER_BODY_NAME CAUSE_DESCRIPTION _DESCRIPTION CYCLE EPA_WBTYPE AL BEAVER CREEK NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 STREAM/CREEK/RIVER AL BRINDLEY CREEK NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 STREAM/CREEK/RIVER AL BUXAHATCHEE CREEK NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 STREAM/CREEK/RIVER AL CAHABA RIVER NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 STREAM/CREEK/RIVER AL CANE CREEK (OAKMAN) NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 STREAM/CREEK/RIVER AL CYPRESS CREEK NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 STREAM/CREEK/RIVER AL DRY CREEK NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 STREAM/CREEK/RIVER AL ELK RIVER NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 STREAM/CREEK/RIVER AL FACTORY CREEK NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 STREAM/CREEK/RIVER AL FLAT CREEK NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 STREAM/CREEK/RIVER AL HERRIN CREEK NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 STREAM/CREEK/RIVER AL HESTER CREEK NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 STREAM/CREEK/RIVER AL LAKE LOGAN MARTIN NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 LAKE/RESERVOIR/POND AL LAKE MITCHELL NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 LAKE/RESERVOIR/POND AL LAKE NEELY HENRY NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 LAKE/RESERVOIR/POND AL LAY LAKE NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 LAKE/RESERVOIR/POND AL LOCUST FORK NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 STREAM/CREEK/RIVER AL MCKIERNAN CREEK NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 STREAM/CREEK/RIVER AL MULBERRY FORK NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 STREAM/CREEK/RIVER AL NORTH RIVER NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 STREAM/CREEK/RIVER AL PEPPERELL BRANCH NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 STREAM/CREEK/RIVER AL PUPPY CREEK NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 STREAM/CREEK/RIVER AL SUGAR CREEK NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 STREAM/CREEK/RIVER AL UT TO DRY BRANCH NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 STREAM/CREEK/RIVER AL UT TO HARRAND CREEK NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 STREAM/CREEK/RIVER AL WEISS LAKE NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 LAKE/RESERVOIR/POND YATES RESERVOIR (SOUGAHATCHEE CREEK AL EMBAYMENT) NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 LAKE/RESERVOIR/POND AR BEAR CREEK NITROGEN NUTRIENTS 2004 STREAM/CREEK/RIVER AR BEAR CREEK LAKE NUTRIENTS NUTRIENTS 2004 LAKE/RESERVOIR/POND AR DAYS CREEK NITROGEN NUTRIENTS 2004 STREAM/CREEK/RIVER AR ELCC TRIB.