Prologue 1 Haggard, Diary of an African Journey. 2 Rian Malan Interview by Tim Adams, Observer Magazine, 25 March 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City Coins Post Al Medal Auction No. 68 2017

Complete visual CITY COINS CITY CITY COINS POSTAL MEDAL AUCTION NO. 68 MEDAL POSTAL POSTAL Medal AUCTION 2017 68 POSTAL MEDAL AUCTION 68 CLOSING DATE 1ST SEPTEMBER 2017 17.00 hrs. (S.A.) GROUND FLOOR TULBAGH CENTRE RYK TULBAGH SQUARE FORESHORE CAPE TOWN, 8001 SOUTH AFRICA P.O. BOX 156 SEA POINT, 8060 CAPE TOWN SOUTH AFRICA TEL: +27 21 425 2639 FAX: +27 21 425 3939 [email protected] • www.citycoins.com CATALOGUE AVAILABLE ELECTRONICALLY ON OUR WEBSITE INDEX PAGES PREFACE ................................................................................................................................. 2 – 3 THE FIRST BOER WAR OF INDEPENDENCE 1880-1881 4 – 9 by ROBERT MITCHELL........................................................................................................................ ALPHABETICAL SURNAME INDEX ................................................................................ 114 PRICES REALISED – POSTAL MEDAL AUCTION 67 .................................................... 121 . BIDDING GUIDELINES REVISED ........................................................................................ 124 CONDITIONS OF SALE REVISED ........................................................................................ 125 SECTION I LOTS THE FIRST BOER WAR OF INDEPENDENCE; MEDALS ............................................. 1 – 9 SOUTHERN AFRICAN VICTORIAN CAMPAIGN MEDALS ........................................ 10 – 18 THE ANGLO BOER WAR 1899-1902: – QUEEN’S SOUTH AFRICA MEDALS ............................................................................. -

'There's a Lot of People Who Say They Were at Rorke's Drift'

‘There’s A Lot of People Who Say They Were At Rorke’s Drift’ The problems which beset those trying to compile a definitive list of defenders. Ian Knight ___________________________________________________________________________ In his seminal work on the rolls of the 24th Regiment at iSandlwana and Rorke’s Drift, The Noble 24th (Savanah Books, 1999), the late Norman Holme observed ruefully that The defenders of Rorke’s Drift were comparatively few in number, furthermore the garrison mainly consisted of soldiers belonging to one Company of a particular Regiment. On the basis of these facts the accurate identification of the individual men present during the action on 22nd-23rd January 1879 would appear to be a relatively simple task; however, such is not the case. Indeed, it is not - nor, nearly fifteen years after Holme made that remark, and despite the continuing intense interest in the subject, is the task likely to get any easier. The fundamental problem lies with the incompleteness of contemporary records. The only valid sources are the rolls compiled by those who were in a position of authority at the time, and, whilst these agree on the majority of those present, there are contradictions, inaccuracies and omissions between them, and the situation is further complicated because it is impossible to arrive at a definitive conclusion on the question of who ought to have been there. The earliest roll of defenders seems to have been compiled by the senior officer at the action, Lieutenant John Chard of the Royal Engineers. As early as 25 January 1879 - two days after the battle - Chard produced an official report of the battle. -

Project Aneurin

The Aneurin Great War Project: Timeline Part 8 - The War Machines, 1870-1894 Copyright Notice: This material was written and published in Wales by Derek J. Smith (Chartered Engineer). It forms part of a multifile e-learning resource, and subject only to acknowledging Derek J. Smith's rights under international copyright law to be identified as author may be freely downloaded and printed off in single complete copies solely for the purposes of private study and/or review. Commercial exploitation rights are reserved. The remote hyperlinks have been selected for the academic appropriacy of their contents; they were free of offensive and litigious content when selected, and will be periodically checked to have remained so. Copyright © 2013-2021, Derek J. Smith. First published 09:00 BST 5th July 2014. This version 09:00 GMT 20th January 2021 [BUT UNDER CONSTANT EXTENSION AND CORRECTION, SO CHECK AGAIN SOON] This timeline supports the Aneurin series of interdisciplinary scientific reflections on why the Great War failed so singularly in its bid to be The War to End all Wars. It presents actual or best-guess historical event and introduces theoretical issues of cognitive science as they become relevant. UPWARD Author's Home Page Project Aneurin, Scope and Aims Master References List FORWARD IN TIME Part 1 - (Ape)men at War, Prehistory to 730 Part 2 - Royal Wars (Without Gunpowder), 731 to 1272 Part 3 - Royal Wars (With Gunpowder), 1273-1602 Part 4 - The Religious Civil Wars, 1603-1661 Part 5 - Imperial Wars, 1662-1763 Part 6 - The Georgian Wars, 1764-1815 Part 7 - Economic Wars, 1816-1869 FORWARD IN TIME Part 9 - Insults at the Weigh-In, 1895-1914 Part 10 - The War Itself, 1914 Part 10 - The War Itself, 1915 Part 10 - The War Itself, 1916 Part 10 - The War Itself, 1917 Part 10 - The War Itself, 1918 Part 11 - Deception as a Profession, 1919 to date The Timeline Items 1870 Charles A. -

The Anglo-Zulu War Battlefields 1878 – 1879

THE ANGLO-ZULU WAR BATTLEFIELDS 1878 – 1879 • Good morning. All of you will be familiar with the memorial of the Zulu Shields in St Michael’s Chapel. An opportunity arose for me to visit the Zulu Battlefields in February this year. I am glad that I took the journey as it was an experience that I will never forget and one that I would like to share with you as I thought it would be helpful in adding to our knowledge of one of the most visually striking of the memorials in the Cathedral. • My talk will cover the origin of the Zulu Shields memorial, the background and reasons for the Anglo-Zulu War, the key personalities involved on both sides and the battlefields where the officers and men of the 80th Regiment of Foot (Staffordshire Volunteers) died. • Zulu Shields memorial. Let me begin with the memorial. The ironwork in the form of the Zulu Shields was done by Hardman of Birmingham with the design including representations of the assegais (spears) and mealie cobs. It was originally placed in the North Transept in 1881where it formed part of the side screen to St Stephen’s Chapel. The Chapel was rearranged in recent times with the Zulu memorial relocated to the South Transept and the white marble reredos now stands against the east wall of the North Choir Aisle. • Turning to the memorial itself, the plaque on the floor reads: “Erected by the Officers, NCOs and Men of the 80th (Staffordshire Volunteers) Regiment who served in South Africa. To the memory of their comrades who fell during the Sekukuni and Zulu Campaigns – 1878-1879”. -

Teaching World History with Major Motion Pictures

Social Education 76(1), pp 22–28 ©2012 National Council for the Social Studies The Reel History of the World: Teaching World History with Major Motion Pictures William Benedict Russell III n today’s society, film is a part of popular culture and is relevant to students’ as well as an explanation as to why the everyday lives. Most students spend over 7 hours a day using media (over 50 class will view the film. Ihours a week).1 Nearly 50 percent of students’ media use per day is devoted to Watching the Film. When students videos (film) and television. With the popularity and availability of film, it is natural are watching the film (in its entirety that teachers attempt to engage students with such a relevant medium. In fact, in or selected clips), ensure that they are a recent study of social studies teachers, 100 percent reported using film at least aware of what they should be paying once a month to help teach content.2 In a national study of 327 teachers, 69 percent particular attention to. Pause the film reported that they use some type of film/movie to help teach Holocaust content. to pose a question, provide background, The method of using film and the method of using firsthand accounts were tied for or make a connection with an earlier les- the number one method teachers use to teach Holocaust content.3 Furthermore, a son. Interrupting a showing (at least once) national survey of social studies teachers conducted in 2006, found that 63 percent subtly reminds students that the purpose of eighth-grade teachers reported using some type of video-based activity in the of this classroom activity is not entertain- last social studies class they taught.4 ment, but critical thinking. -

A Case Study of the Natal Witness

ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES IN THE SOUTH AFRICAN MEDIA: A CASE STUDY OF THE NATAL WITNESS by MARYLAWHON Submitted in partial fulfillment ofthe academic requirements for the degree of Master in Environment and Development in the Centre for Environment and Development, School ofApplied Environmental Sciences University ofKwaZulu-Natal Pietermaritzburg 2004 ABSTRACT The media has had a significant impact on spreading environmental awareness internationally. The issues covered in the media can be seen as both representative of and an influence upon the heterogeneous public. This paper describes the environmental reporting in the South African provincial newspaper, the Natal Witness, and considers the results to both represent and influence South African environmental ideology. Environmental reporting In South Africa has been criticised for its focus on 'green' environmental issues. This criticism is rooted in the traditionally elite nature of both the media and environmentalists. However, both the media and environmentalists have been noted to be undergoing transformation. This research tests the veracity of assertions that environmental reporting is elitist, and has found that the assertions accurately describe reporting in the Witness. 'Green' themes are most commonly found, and sources and actors tend to be white and men. However, a broad range of discourses were noted, showing that the paper gives voice to a range of ideologies. These results hopefully will make a positive contribution to the environmental field by initiating debate, further studies, and reflection on the part of environmentalists, journalists, and academics on the relationship between the media and the South African environment. The work described in this dissertation was carried in the Centre for Environment and Development, University ofKwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, from July 2004 to December 2004, under the supervision ofProfessor Robert Fincham. -

A Teaching Guide by William Bigelo W Introduction and Summary of Lessons

Witness Apartheid: A Teaching Guide by William Bigelo w Introduction and Summary of Lessons . 3 Day One: Apartheid Simulation . ?C Day 'bo: Film-Witness to Apartheid . 7 Day Three: Role Play4 New Breed of Children" . 9 Day Four: Role Play4 New Breed of Children" (completion) . 11 Day Five: South Africa Letter Writing. 13 Reference Materials . 14 Additional Reading Suggestions for Student. Reading Suggestions for lkachers Additional Film Suggestions Student Handout #1 Privileged Minority. .......................... 15 Student Handout #2 The Bantustans . 16 Student Handout #3 Human Rights Fact Sheet. 17 Student Handout #4 Learning Was Defiance . 19 Student Handout #5 South African Student . 21 Student Handout #6 Challenging "Gutter Education". 23 a1987 Copyright by William Bigelow Published by The Southern Africa Media Center California Newsreel, 630 Natoma Street, San Francisco, CA 94103, (415) 621-6196 This "Raching Guide" made possible by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. Design, typesetting, and production by Allogmph, San Francisco Film, Witness to Apartheid (classroom version): 35 minutes, 1986 Produced and directed by Sharon Sopher Co-produced by Kevin Harris Classroom version of Witness to Apartheid made possible by the Aaron Diamond Foundation. Introduction The story Witness to Apartheid tells is stark: children in South Africa - the same age as students we teach - are today being beaten, detained, even tortured. As one recent human rights report summarizes, the South African government is waging a 'kar against children.'' The images of Witness to Apartheid are not seen on the evening news: a father shares his feelings about the cold-blooded murder of his son by a South African policeman; a young woman describes the hideous torture she experienced while in police custody; a young man mumbles that he doesn't want to go on living - his beatings by security forces have left him permanently disabled. -

Isandlwana, Rorke's Drift And

ISANDLWANA, RORKE’S DRIFT AND THE LIMITATIONS OF MEMORY By Ian Knight ___________________________________________________________________________ In his memoir of a long and active military career, General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien recalled a famous incident from the battle of Isandlwana; I will mention a story which speaks for the coolness and discipline of the regiment. I, having no particular duty to perform in camp, when I saw the whole Zulu army advancing, had collected camp stragglers, such as artillerymen in charge of spare horses, officers’ servants, sick, etc, and had taken them to the ammunition-boxes, where we broke them open as fast as we could, and kept sending out the packets to the firing line. In those days the boxes were screwed down and it was a very difficult job to get them open, and it was owing to this battle that the construction of ammunition boxes was changed. When I had been at this for some time, and the 1/24th had fallen back to where we were, with the Zulus following closely, Bloomfield, the quartermaster of the 2/24th, said to me in regard to the boxes I was then breaking open, ‘For heaven’s sake, don’t do that, man, for it belongs to our battalion.’ And I replied, ‘Hang it all, you don’t want a requisition now, do you?’ It was about this time, too, that a Colonial named Du Bois, a wagon-conductor, said to me, ‘The game is up. If I had a good horse I would ride straight to Maritzburg.’(1). It’s a powerful image, that glimpse of the meticulous Quartermaster, sticking to his orders at the obvious expense of his duty, and it strikes deep cords with modern preconceptions regarding the apparent lack of flexibility and imagination which prevailed in the British Army of the high-Victorian era. -

Chapter Title

The National Archive (Kew) War Office Series Anglo-Zulu War WO 30/129 Copies of correspondence principally between the Adjutant-General (General C.H. Ellice) and the General Officer Commanding, Cape of Good Hope, (Lt.-General Lord Chelmsford) and memoranda relating to the Isandlwana disaster of 21 and 22 January 1879. (15 pp.) WO 32/5028 Prince Imperial Louis Napoleon: Confirmation of death of the Prince in action by Lord Chelmsford and the institution of an enquiry. (3 pp.) WO 32/5029 Report of the suspected death of the Prince and of the condition of animal transport. (3 pp.) WO 32/5030 An account of the action in which the Prince was killed. This file has been lost by TNA! WO 32/5031 Papers relating to court of enquiry and court martial, involving Lieut. Carey, into circumstances of death of the Prince. (5 pp.) WO 32/5032 Operations against Zulus and movement of the Prince’s body. (2 pp.) WO 32/5033 General Clifford forwarding copies of papers relating to death of the Prince and arrangements for his body to be shipped to England. (25 pp.) WO 32/5034 Letter of thanks on behalf of the French Empress for honour paid to the Prince at his funeral. (2 pp.) WO 32/5035 Papers relating to identification of body. (3 pp) WO 32/5036 Condition of the body on arrival in England. (Not available) WO 32/5037 Acknowledgement of receipt at Public Record Office of Notarial Instrument relating to identification of body. (Not available) WO 32/7382 Victoria Cross: Award to Capt. -

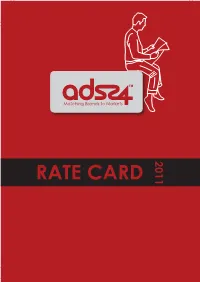

RATE CARD ROP Rates Summary (MON-FRI) 1 Jan - 31 Dec 2011

2011 RATE CARD ROP Rates Summary (MON-FRI) 1 Jan - 31 Dec 2011 Beeld (Mon, Tues) Beeld (Wed, Thurs, Fri) BEELD BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC BEELD BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC Beeld Main Body R163.10 R228.60 R228.60 R228.60 Beeld Main Body R169.40 R237.40 R237.40 R237.40 Sake 24 R164.00 R192.00 R230.00 R230.00 Sake 24 R164.00 R192.00 R230.00 R230.00 Sport 24 R163.10 R228.60 R228.60 R228.60 Sport 24 R169.40 R237.40 R237.40 R237.40 BEELD BEELD SUPPLEMENTS BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC BEELD SUPPLEMENTS BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC Jip R127.00 R172.50 R172.50 R172.50 Leefstyl R148.90 R205.50 R 205.50 R205.50 Buite Beeld R146.10 R201.60 R201.60 R201.60 Motors R148.90 R205.50 R 205.50 R205.50 Vrydag R148.90 R205.50 R 205.50 R205.50 BEELD Oos Beeld R 46.10 R 64.80 R 64.80 R 64.80 Tshwane Beeld R 86.00 R113.60 R 113.60 R113.60 Mpumalanga Beeld R 42.00 R 60.10 R 60.10 R 60.10 Noordwes Beeld R 42.00 R 60.10 R 60.10 R 60.10 Wes Beeld R 40.90 R 54.60 R 54.60 R 54.60 Huisgids R 86.00 R113.60 R 113.60 R113.60 Die Burger (Mon, Tues) Die Burger (Wed, Thurs, Fri) DIE BURGER Wes BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC DIE BURGER Wes BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC Burger Wes Main Body R107.70 R125.10 R142.40 R165.30 Burger Wes Main Body R111.90 R130.00 R148.40 R171.70 Burger Wes Promosies R107.70 R125.10 R142.40 R165.30 Burger Wes Promosies R111.90 R130.00 R148.40 R171.70 Burger Wes Sake 24 R103.00 R119.00 R157.00 R157.00 Burger Wes Sake 24 R103.00 R119.00 R157.00 R157.00 Burger Wes Sport 24 R107.70 R125.10 R142.40 R165.30 Burger Wes Sport 24 R111.90 R130.00 R148.40 R171.70 Jip Wes R107.70 R125.10 R142.40 R165.30 Leefstyl -

Publications Brochure Newspapers

NEWS TRAVEL LIFESTYLE MEN SCIENCE & TECH WOMEN ENTERTAINMENTSPORT 2019 Beeld 3 Rapport 4 The Witness 5 NEWSPAPERS Sunday Sun 6 Daily Sun 7 Die Burger 8 Copyright © 2019 Media24 Volksblad 9 City Press 10 DistrictMail 11 Hermanus Times 12 Paarl Post 13 Weslander 14 Worcester Standard 15 3 Beeld is an award-winning Afrikaans newspaper that’s published six days a week in Gauteng, Limpopo, Mpumalanga and North West. TARIFFS Newspapers Cover price Days of Region Monthly the week debit order Beeld Monday - R12.50 Gauteng R231 Monday - Friday Friday issue Beeld Monday - R12.50 Gauteng R280 Monday - Saturday Friday issue Saturday R13.50 Gauteng issue Beeld R12.50 Saturday only Gauteng R50 Saturday only Copyright © 2019 Media24 4 Rapport offers exclusive news on politics, sport and people, 16 pages with opinions, analyses and book reviews in Weekliks, lifestyle news in Beleef, business news in Sake, job opportunities in Loopbane and a newsmaker profile by Hanlie Retief. TARIFFS Newspapers Cover price Days of Region Monthly the week debit order Rapport R12.50 Sunday only National R101 Copyright © 2019 Media24 5 The Witness is a broadsheet morning newspaper that’s published Monday to Friday in KwaZulu-Natal. Weekend Witness is a tabloid which appears on Saturdays and provides a mix of news, commentary, sport, personal finance, entertainment and a popular weekly property sales supplement. TARIFFS Newspapers Cover price Days of Region Monthly the week debit order The Witness Monday - R7.70 KZN R119 Monday - Friday Friday issue The Witness Monday - R7.70 KZN R144 Monday - Saturday Friday issue Saturday R7.90 KZN issue The Witness R7.90 Saturday only KZN R25 Saturday only Copyright © 2019 Media24 6 Sunday Sun is an exciting Sunday tabloid filled with entertainment and lots of celebrity news. -

THE VICTORIAN SOLDIER in AFRICA and the 2/24Th, Largely Composed of Short-Service Soldiers, Had Arrived in March 1878

CHAPTER TWO Campaigning in southern Africa Eyewitness accounts are among the many sources used in the volumi- nous literature on the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879, a major test of British command, transport arrangements, and the fighting qualities of the short-service soldier. Quite apart from the writings of the late Frank Emery, who refers to eighty-five correspondents in The Red Soldier and another twenty-four in his chapter on that campaign in Marching Over Africa,1 there are invaluable edited collections of letters from individ- ual officers by Sonia Clark2 and Daphne Child,3 and by Adrian Greaves and Brian Best.4 While the papers and journals of the British command- ing officers have been splendidly edited,5 some perspectives of officers and other ranks appear in testimony before official inquiries (into the disasters at Isandlwana and Ntombe, and the death of the Prince Impe- rial)6 and among the sources used by F. W. D. Jackson and Ian Knight, and by Donald Morris in his classic volume The Washing of the Spears.7 Yet the letters found by Emery – the core of the material used for the views of regimental officers and other ranks8 – represent only a fraction of the material written during the Anglo-Zulu War. Many more officers and men kept diaries or wrote to friends and family, chronicling their exploits in that war and its immediate predecessors, the Ninth Cape Frontier War (1877–78) and the campaign against the Pedi chief, Sekhukhune (1878). While several soldiers complained about the postal arrangements or the scarcity of stamps and paper, they still wrote let- ters, even improvising, as Corporal Thomas Davies (2/24th) did, by using gunpowder as ink.9 Their correspondence forms the core of this Chapter’s review of campaigning in southern Africa.