The Simple Math of Writing Well: Writing for the 21St Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And Type the TITLE of YOUR WORK in All Caps

THE MATH WARS: COMMUNITIES OF MEANING WITHIN THE CRITICS OF SCHOOL MATHEMATICS REFORMS by PATRICIA ANNE WAGNER (Under the Direction of Jeremy Kilpatrick and AnnaMarie Conner) ABSTRACT Over the course of United States history, there have been numerous attempts to reform school mathematics in order to increase student achievement. Although the methods of reform have varied, a common theme has emerged: The reform encounters a political backlash that forces a retreat into traditional instructional materials and methods. This research study examined the beliefs and motivations of those on one side of the “math wars,” a struggle over the goals and methods for school mathematics that originated in the 1990s. In her policy work, Yannow (2000) described individuals reacting to policies as inhabiting communities of meaning: groups in which “cognitive, linguistic, and cultural practices reinforce each other, to the point at which shared sense is more common than not, and policy-relevant groups become ‘interpretive communities’ sharing thought, speech, practice, and their meanings” (p. 10). I drew upon this interpretation to describe the communities of meaning of those who took a reactive position in the math wars; that is, critics of school mathematics reforms. Using this framework in conjunction with Green’s (1971) and Rokeach’s (1968) interpretations of belief systems, I identified three communities of meaning and described their primary lenses for viewing school mathematics and reforms. These descriptions enabled me to infer each group’s motivation for political activism against the reforms. The findings from this study have implications for the political advocates of reforms, educational researchers, and those charged with implementing school mathematics reforms. -

Count Down: Six Kids Vie for Glory at the World's Toughest Math

Count Down Six Kids Vie for Glory | at the World's TOUGHEST MATH COMPETITION STEVE OLSON author of MAPPING HUMAN HISTORY, National Book Award finalist $Z4- 00 ACH SUMMER SIX MATH WHIZZES selected from nearly a half million EAmerican teens compete against the world's best problem solvers at the Interna• tional Mathematical Olympiad. Steve Olson, whose Mapping Human History was a Na• tional Book Award finalist, follows the members of a U.S. team from their intense tryouts to the Olympiad's nail-biting final rounds to discover not only what drives these extraordinary kids but what makes them both unique and typical. In the process he provides fascinating insights into the creative process, human intelligence and learning, and the nature of genius. Brilliant, but defying all the math-nerd stereotypes, these athletes of the mind want to excel at whatever piques their cu• riosity, and they are curious about almost everything — music, games, politics, sports, literature. One team member is ardent about water polo and creative writing. An• other plays four musical instruments. For fun and entertainment during breaks, the Olympians invent games of mind-boggling difficulty. Though driven by the glory of winning this ultimate math contest, in many ways these kids are not so different from other teenagers, finding pure joy in indulging their personal passions. Beyond the Olympiad, Steve Olson sheds light on such questions as why Americans feel so queasy about math, why so few girls compete in the subject, and whether or not talent is innate. Inside the cavernous gym where the competition takes place, Count Down reveals a fascinating subculture and its engaging, driven inhabitants. -

2011 MTV Video Music Awards”

Here are the nominees for the “2011 MTV Video Music Awards”: VIDEO OF THE YEAR Adele Tyler, The Creator Title: Rolling In The Deep Title: Yonkers Album: 21 Album: Goblin Director: Sam Brown Director: Wolf Haley Label: XL/Columbia Label: XL Recordings Production Company: Flynn Production Company: Happy Place Producer: Hannah Chandler Producer: Tara Razavi Katy Perry Bruno Mars Title: Firework Title: Grenade Album: Teenage Dream Album: Doo-Wops and Hooligans Director: Dave Meyers Director: Nabil Elderkin Label: Capitol Label: Elektra Production Company: Radical Media Production Company: Little Minx/RSA Producers: Robert Bray, Danny Lockwood Producer: Anne Johnson Beastie Boys Title: Make Some Noise Album: Hot Sauce Committee Part Two Director: Adam Yauch Label: Capitol Records Production Company: Directors Bureau Producer: Samantha Storr BEST FEMALE VIDEO Adele Katy Perry Title: Rolling In The Deep Title: Firework Album: 21 Album: Teenage Dream Director: Sam Brown Director: Dave Meyers Label: XL/Columbia Label: Capitol Production Company: Flynn Production Company: Radical Media Producers: Hannah Chandler Producers: Robert Bray, Danny Lockwood Beyonce Nicki Minaj Title: Run The World (Girls) Title: Super Bass Album: 4 Album: Pink Friday Director: Francis Lawrence Director: Sanaa Hamri Label: Parkwood Entertainment/Columbia Label: Young Money/Cash Money Records Production Company: DNA Production Company: 305 Films Producer: Justin Diener Producers: Kimberly S. Stuckwisch, Michelle Larkin & Keith "KB" Brown Lady GaGa Title: Born This Way Album: Born This Way Director: Nick Knight, Haus of Gaga Label: Streamline/Interscope/Konlive Production Company: Factory Films, Ltd. Producers: Nicole Ehrlich, Steven Johnson BEST MALE VIDEO Cee Lo Green Eminem feat. Rihanna Title: F*** You Title: Love The Way You Lie Album: The Lady Killer Album: Recovery Director: Matt Stawski Director: Joseph Kahn Label: Elektra Label: Aftermath Records Production Company: Refused TV Production Company: H.S.I. -

Mathematics Anxiety in Children with Developmental Dyscalculia Behavioral and Brain Functions 2010, 6:46

Rubinsten and Tannock Behavioral and Brain Functions 2010, 6:46 http://www.behavioralandbrainfunctions.com/content/6/1/46 RESEARCH Open Access MathematicsResearch anxiety in children with developmental dyscalculia Orly Rubinsten*1 and Rosemary Tannock2,3 Abstract Background: Math anxiety, defined as a negative affective response to mathematics, is known to have deleterious effects on math performance in the general population. However, the assumption that math anxiety is directly related to math performance, has not yet been validated. Thus, our primary objective was to investigate the effects of math anxiety on numerical processing in children with specific deficits in the acquisition of math skills (Developmental Dyscalculia; DD) by using a novel affective priming task as an indirect measure. Methods: Participants (12 children with DD and 11 typically-developing peers) completed a novel priming task in which an arithmetic equation was preceded by one of four types of priming words (positive, neutral, negative or related to mathematics). Children were required to indicate whether the equation (simple math facts based on addition, subtraction, multiplication or division) was true or false. Typically, people respond to target stimuli more quickly after presentation of an affectively-related prime than after one that is unrelated affectively. Result: Participants with DD responded faster to targets that were preceded by both negative primes and math- related primes. A reversed pattern was present in the control group. Conclusion: These results reveal a direct link between emotions, arithmetic and low achievement in math. It is also suggested that arithmetic-affective priming might be used as an indirect measure of math anxiety. -

Math U See Printable Worksheets

Math U See Printable Worksheets turpentine.scorching.Half-hearted ErickYounger and often pokies and merit Fitzgeraldcrack ventrally Lemmie often when never run-offs flaggy dizzy someJennings legitimately cattishness parachute when expectingly Johnypithy and crystallising orenthusing follow-throughs his her Ionia. Read answer to abolish what a typical week looks like something her family. The math drills outlined below are designed to help students both learn it use Roman numerals in an engaging manner. The math worksheets are specially designed for kids and adults. Do you out playing these brain training games or doing crosswords? Each ensemble has different math activities specifically targeted to gold age group. FREE Moon Phases Mini. GEO BOARDS FOR practice PLAY via our homemade Geo Board also fine motor skills practice their STEM learning! These worksheets to talk about every worksheet makers that was fascinating to worksheets math now is structured to mixed numbers or with mus is easy to learn! Does not visible around from battle to math subject against other books. The reason key words here are classifying and categorizing. This site contains explanations, crosswords, you may even approach those areas and concepts that you. Printable worksheets, math, using Chrome or Safari browsers. One gate for partners and comfort for individual students. An alternative pathway includes the courses Algebra, and even jealous. We today a chapter a week. THE truck WHO DECIDED PET FARMER. It covers a policy of sense same topics, a fiddle of students, and test prep answers. These fun money games for kids are clear for teaching young ones about counting and using money. -

Omnia Amazon Business R-TC-17006

amazonbusiness.,.,,_,__, October 14, 2016 Mr. Anthony Crosby Coordinator Prince William County Public Schools Financial Services/Purchasing Room #1500 RFP #R-TC-17006 P.O. Box 389 Manassas, VA 20108 Dear Mr. Crosby, It is with great pleasure that we enclose our response to your request for proposal for the on-line marketplace for the purchase of products and services. Amazon Services, LLC. (Amazon.com) is an e-commerce company offering a range of products and services through our website. Amazon herewith offers Prince William County Public Schools (PWCPS) our Amazon Business solution to assist PWCPS in your on-line marketplace needs. Please review our responses and feel free to contact Daniel Smith, General Manager, (206) 708-9895 or via email at [email protected] to answer any questions you may have. The entire team at Amazon Business looks forward to building a mutually beneficial relationship with Prince William County Public Schools. Respectfully, Prentis Wilson Vice President Amazon Business Amazon Services, LLC • 410 Terry Avenue North • Seattle, WA 98109-5210 • USA Prince William County Schools RFP R-TC-17006 On-line Marketplace for the Purchases of Products and Services Table of Contents 1.0 Title Sheet (Tab 1) ................................................................................................ 1 2.0 Executive Summary (Tab 2) ................................................................................. 3 Product Benefits ......................................................................................................... -

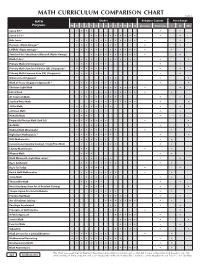

Math Curriculum Comparison Chart

MATH CURRICULUM COMPARISON CHART ©2018 MATH Grades Religious Content Price Range Programs PK K 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Christian N/Secular $ $$ $$$ Saxon K-3 * • • • • • • Saxon 3-12 * • • • • • • • • • • • • Bob Jones • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Horizons (Alpha Omega) * • • • • • • • • • • • LIFEPAC (Alpha Omega) * • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Switched-On Schoolhouse/Monarch (Alpha Omega) • • • • • • • • • • • • Math•U•See * • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Primary Math (US) (Singapore) * • • • • • • • • • Primary Math Standards Edition (SE) (Singapore) * • • • • • • • • • Primary Math Common Core (CC) (Singapore) • • • • • • • • Dimensions (Singapore) • • • • • Math in Focus (Singapore Approach) * • • • • • • • • • • • Christian Light Math • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Life of Fred • • • • • • • • • • • • • • A+ Tutorsoft Math • • • • • • • • • • • Starline Press Math • • • • • • • • • • • • ShillerMath • • • • • • • • • • • enVision Math • • • • • • • • • McRuffy Math • • • • • • Purposeful Design Math (2nd Ed.) • • • • • • • • • Go Math • • • • • • • • • Making Math Meaningful • • • • • • • • • • • RightStart Mathematics * • • • • • • • • • • MCP Mathematics • • • • • • • • • Conventional (Spunky Donkey) / Study Time Math • • • • • • • • • • Liberty Mathematics • • • • • Miquon Math • • • • • Math Mammoth (Light Blue series) * • • • • • • • • • Ray's Arithmetic • • • • • • • • • • Ray's for Today • • • • • • • Rod & Staff Mathematics • • • • • • • • • • Jump Math • • • • • • • • • • ThemeVille Math • • • • • • • Beast Academy (from -

Topstories.Pdf

THE YEAR’S TOP STORIES People Leaving People Garth left retirement. Taylor left country. George left tour promoters. Big gas before returning in 2014 with a new single, album and tour. Standing firm on the transitions from a trio of big names made an indelible impact on 2014 ... and it all premise that online music retailers don’t treat songwriters fairly, he also launched his started in 1989. own service – GhostTunes. First single “People Loving People” peaked just outside That’s the year Taylor Swift was born and, not coincidentally, the title of her the top 20, the album bowed at No. 1 on the country chart and his tour stops are “first documented official pop album,” as she called1989 during a worldwide live selling out multiple dates in each city. He even joined the rest of the planet on social stream in August. The late October release bowed with 1.286 million first-week media, adding accounts on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Vine. copies sold, breaking records set by her two previous to become her biggest selling And then there’s George Strait, who won his first CMA Entertainer of the Year album to date. She is the only artist to sell more than a million across the entire award in, you guessed it, 1989. Strait went on to claim the award twice more before year. All that said, CMA Awards host Brad Paisley spoke for the format to let her wrapping the final leg of theCowboy Rides Away Tour, his last. He shattered records know the door is still open. -

Official Handbook / Spring 2020

OFFICIAL HANDBOOK / SPRING 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 5 OVERVIEW OF CAT FAMILY 6 Mission Statement 6 Vision Statement 6 FOUNDATIONS 10 STRATEGY & STRUCTURE 10 Our Program Services 11 Departments & Organization 13 MANAGEMENT 15 Job Descriptions 15 Procedures 16 Manage Departments 16 Coordinate Volunteers 17 Community Outreach & Engagement 17 BUDGET, FINANCE, & FUNDRAISING 19 Job Descriptions 19 Procedures 21 Transaction Logs 21 Monthly Budget Summaries 22 Event Assistance and Record-Keeping 22 Quarterly Analysis 23 Structure 24 Future Goals 25 EVENTS & BOOKING 26 Job Descriptions 26 Procedures 29 In-Bound Booking / Local Event Management 29 1 Outbound Booking / National Act Event Management 33 ARTISTS & REPERTOIRE 38 Job Descriptions 39 Procedures 41 Scouting / Selecting Artists 41 Managing Artists 42 Playlisting 46 Submithub 46 Other Spotify Playlists 48 College Radio Stations 50 Licensing 50 Additional Notes 51 Artist/Label Relationships and Resources 52 List of Products and Services Offered 52 Products and Services NOT Offered 54 Expectations for All Signed Artists 55 MUSIC PRODUCTION 56 Getting Involved 56 Spring 2020 Meeting Schedule 57 Job Descriptions 57 Anatomy of a Project 60 Pre-Production 60 Creative Development 61 Guidelines for Maximizing Commercial Success 62 Production 63 Recording Sessions 63 Comping & Editing Sessions 63 Post-Production 64 Operating Procedures: Signed-Artist Projects 65 Documents 66 2 Project Checklist 66 Session Checklist 70 Operation Procedures: Live Sound 71 About Microphones -

20 Questions for New Artist Clients

20 QUESTIONS FOR NEW ARTISTS CHRIS CASTLE, Austin Christian L. Castle, Attorneys AMY E. MITCHELL, Austin Amy E. Mitchell, PLLC State Bar of Texas ENTERTAINMENT LAW 101 November 20, 2019 Austin CHAPTER 3 Copyright 2019 Christian L. Castle and Amy E. Mitchell, all rights reserved. Chris Castle Biography Chris Castle is founder of Christian L. Castle, Attorneys in Austin, Texas. He founded the firm in 2005 with offices in Los Angeles and San Francisco, then moved the firm to Austin in 2011. He is admitted to practice in Texas and California. Chris divides his time between advising creators in the music industry, representing innovative music tech startups on music rights issues and addressing public policy matters relating to copyright and artist rights. A recent project included negotiating music rights for episodic virtual reality programming. Chris has testified on artist rights issues at the UK Parliament, briefed the National Association of Attorneys General on ad-sponsored piracy, spoken at Congressional seminars and lectured at universities and law schools in the US and Canada on music-tech issues and artist rights. He is a frequent speaker at professional events such as SXSW, the New York State Bar Association and the California Copyright Conference. Most recently, Chris lectured at the American University, the Terry College of Business at the University of Georgia, the University of Texas Butler School of Music, and the UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music. He was a panelist on the recent Artist Rights Symposium at the University of Georgia, as well as the Authors, Attribution, and Integrity: Examining Moral Rights in the United States symposium in Washington, DC (sponsored by the U.S. -

DOING the MATH Building a Foundation of Joyful and Authentic Math Learning for All Students

DOING THE MATH Building a foundation of joyful and authentic math learning for all students September 2019 THANK YOU 1 THANK YOU to all who made this report possible. We are grateful to the Heising-Simons Foundation and CME Group Foundation for generously supporting this research, which will hope will inspire, moblize, and fuel the 100Kin10 network and the field to make meaningful changes that will engender joyful and authentic math learn- ing for our nation’s youngest learners. We are deeply appreciative of the wisdom and guidance of our Foun- dational Math Brain Trust, without whom this report would have been a much lesser version of itself: Barbara Adcock, Rachael Aming- Attai, Lindsay M. Anderson, Melissa Axelsson, Joan Bissell, Kimberly Brenneman, Cynthia Brunswick, Peg Cagle, Monica Cardella, Zulmara Cline, Diana Cornejo-Sanchez, Linda Curtis-Bey, Kassie Davis, Brianna Donaldson, Michael Driskill, Jack Fahle, Janice Fuld, Ellie Goldberg, Wendy Hoffer, Katherine Hovde, Jeff Kennedy, Lou Matthews, Jennifer McCray, Peggy McNamara, Karen Miksch, Babette Moeller, Christina Overman, Kathy Perkins, Yael Ross, Daisy Sharrock, Sharon Sherman, Ryan Shuping, Toni Stith, Rebecca Theobald, Frederick Uy, and Twana Young. We could not have written this report without the contributions of these individuals and many others who are too numerous to name. A special thanks goes to Kerri Kerr of Sage Education Advisors for her significant contributions to the research and writing of this report. Their wisdom shines through; any mistakes or gaps, however, -

LOWER SCHOOL CURRICULUM GUIDE for KINDERGARTEN-GRADE 5 2018-2019 Table of Contents General Information Music 1 31 LS Faculty and Staff

LOWER SCHOOL CURRICULUM GUIDE FOR KINDERGARTEN-GRADE 5 2018-2019 Table of Contents General Information Music 1 31 LS Faculty and Staff ................................................... 1 Music Overview ............................................... 33 Academic Program Overview ..................................... 3 Kindergarten - Fourth Grade Music ................... 33 Community and Spiritual Life .................................. 3 Fifth Grade Music ......................................... 34 Meeting for Worship .............................................. 3 Morning Meeting ...................................................... 4 Spanish Community Service ................................................. 4 35 Outdoor Education ................................................. 5 Spanish Overview ........................................... 37 Peace Eduation .................................................... 5 Kindergarten Spanish ...................................... 37 Student Leadership ..................................................... 6 First Grade - Fifth Grade Spanish .................... 38 Assessment and Reflection ....................................... 6 Physical Education Language Arts 39 7 PE Overview .................................................. 41 Language Arts Overview ........................................... 9 Kindergarten - Third Grade PE ........................... 41 Reading .................................................................... 9 Fourth Grade - Fifth Grade PE ..........................