1996 Human Rights Report: Liberia Page 1 of 14

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women and Post-Conflict Development: a Case Study on Liberia

Women and Post-conflict Development: A Case Study on Liberia By William N. Massaquoi B.Sc. in Economics University of Liberia Monrovia, Liberia (1994) Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master in City Planning at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2007 C 2007 William N. Massaquoi. All Rights Reserved The author here by grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part. j I . Author Department of Urbpn Studies and Planning May 24, 2007 Certified by Studies and Planning I)ep•'•ent of LTrb)m May 24, 2007 ,.--_ - Professor Balakrishnan Rajagopal | • Department of Urban Studies and Planning Thesis Supervisor Accepted by = p t I Professor Langley Keyes Chair, MCP Committee MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE Department of Urban Studies and Planning OF TECHNOLOGY JUL 1 8 2007 L; ES-.- ARCHIVES Women and Post-conflict Development: A Case Study on Liberia By William Massaquoi Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning On May 24, 2007 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of City Planning Abstract Liberia seems an ostensible 'poster child' in light of the call by women's rights advocates to insert women in all aspects of the political, social, and economic transition in post-conflict countries. Liberia has elected the first female African President and women head the strategic government ministries of Finance, Justice, Commerce, Gender, Youth and Sports and National Police. Women also helped to secure an end to fourteen years of civil war. -

The Role of Civil Society in National Reconciliation and Peacebuilding in Liberia

International Peace Academy The Role of Civil Society in National Reconciliation and Peacebuilding in Liberia by Augustine Toure APRIL 2002 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The International Peace Academy wishes to acknowledge the support provided by the Government of the Netherlands which made the research and publication of this study possible. ABOUT IPA’S CIVIL SOCIETY PROGRAM This report forms part of IPA’s Civil Society Project which, between 1998 and 1999, involved case studies on the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea-Bissau. IPA held a seminar, in partnership with the Organization of African Unity (OAU), in Cape Town in 1996 on “Civil Society and Conflict Management in Africa” consisting largely of civil society actors from all parts of Africa. An IPA seminar organized in partnership with the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA) in Senegal in December 1999 on “War, Peace and Reconciliation in Africa” prominently featured civil society actors from all of Africa’s sub-regions. In the current phase of its work, IPA Africa Program’s Peacebuilding in Africa project is centered around the UN community and involves individuals from civil society, policy, academic and media circles in New York. The project explores ways of strengthening the capacity of African actors with a particular focus on civil society, to contribute to peacemaking and peacebuilding in countries dealing with or emerging from conflicts. In implementing this project, IPA organizes a series of policy fora and Civil Society Dialogues. In 2001, IPA initiated the Ruth Forbes Young fellowship to bring one civil society representative from Africa to spend a year in New York. -

Corruption Scandals in Women's Path to Executive Power Sutapa Mitra

Corruption Scandals in Women’s Path to Executive Power Sutapa Mitra Thesis submitted to the University of Ottawa in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Political Science School of Political Studies Faculty of Social Sciences University of Ottawa © Sutapa Mitra, Ottawa, Canada, 2021 ii CORRUPTION AND WOMEN STATE EXECUTIVES ABstract This paper explores the relationship between corruption scandals and women’s path to executive power using the following research question: How do corruption scandals impact women’s path to executive power? This examination contributes to the literature on women executives, corruption and gender. I will trace women’s path to executive power and the impact of corruption scandal at different stages of their rise to national office using three case studies: Angela Merkel, Michelle Bachelet, and Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf. I will explore the impact of corruption scandals on their respective paths to national executive power using Beckwith’s removal and deferral framework. The findings showcase that corruption scandals can be beneficial to women’s rise to executive power in party leadership contests in parliamentary systems, and during national elections if corruption is a salient electoral topic and cultural gendered beliefs frame women candidates as less corrupt. For Merkel, corruption scandal was significant in accessing party leadership. For Johnson-Sirleaf, corruption scandal was significant during national elections. For Bachelet, corruption scandal had an ambiguous effect. Nevertheless, Bachelet’s case informs a theoretical contribution by demonstrating that deferral can occur without removal and still facilitate senior women’s path to power under Beckwith’s framework. Keywords: women executives, women head of government, women prime ministers, women presidents, women chancellor, corruption, corruption scandal, women’s path to national leadership. -

Liberia October 2003

Liberia, Country Information Page 1 of 23 LIBERIA COUNTRY REPORT OCTOBER 2003 COUNTRY INFORMATION & POLICY UNIT l Scope of the document ll Geography lll Economy lV History V State Structures Vla Human Rights Issues Vlb Human Rights - Specific Groups Vlc Human Rights - Other Issues Annex A - Chronology Annex B - Political Organisations Annex C - Prominent People Annex D - References to Source Material 1. Scope of Document 1.1 This report has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The report has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The report is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. These sources have been checked for currency, and as far as can be ascertained, remained relevant and up to date at the time the document was issued. 1.4 It is intended to revise the report on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. 2. Geography 2.1 The Republic of Liberia is a coastal West African state of approximately 97,754 sq kms, bordered by Sierra Leone to the west, Republic of Guinea to the north and Côte d'Ivoire to the east. -

Republic of Liberia Executive Mansion Monrovia, Liberia

REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA EXECUTIVE MANSION MONROVIA, LIBERIA Office of the Press Secretary to the President Cell: 0886-580034/0777580034 Email: [email protected] [email protected] As Part of 52nd Anniversary of Armed Forces Day, President Sirleaf Commissions Two Defender Boats, Named for Two Liberian Women, to Patrol Nation’s Territorial Waters (MONROVIA, LIBERIA – Monday, February 10, 2014) The Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of Liberia (AFL), President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, has commissioned two Defender boats to be used by the Liberian Coast Guard. The commissioning ceremony is part activities marking the 57th Anniversary of Armed Forces Day. According to an Executive Mansion release, the two boats, donated by the United States Government, have been named in honor of two eminent Liberian women – Madam Ruth Sando Perry, and Dr. Mary Antoinette Brown Sherman. Madam Perry was former Chairman of the erstwhile Council of State that led Liberia to its first post-war election in 1997; while Dr. Brown Sherman was the first and only female President of the University of Liberia. In brief remarks at the Liberian Coast Guard Headquarters on Bushrod Island, President Sirleaf thanked the U.S. Government and attributed a large portion of the AFL reconstruction to U.S. assistance, which she said it is the result of great partnership between the two countries. “Let me say how pleased we are with the partnership that Liberia enjoys with the United States; the peace that we have today can in large measure be attributed to this partnership that has helped us to produce an army of which we are all proud because of their professionalism, commitment and what they do to preserve the peace in our country,” the Liberian leader said joyously. -

“Pray the Devil Back to Hell:” Women's Ingenuity in the Peace Process In

This background paper has been produced for a workshop on “Women's Political Participation in Post- Conflict Transitions”, convened by Peacebuild in Ottawa on March 23, 2011 Background brief with the support of the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. It 1 was researched and written “Pray the Devil Back to Hell:” by Ecoma Alaga. Women‟s ingenuity The Peacebuilding and Conflict Prevention consultation series seeks to in the peace process in Liberia bring together expert civil society practitioners, Ecoma Alaga academics and Government of Canada officials to generate up-to-date information and analysis, as well as policy and INTRODUCTION programming options to Liberia is a country in transition from war to peace. The end of the respond to developments and 14-year war (1989-2003) and the journey towards post-conflict emerging trends in peacebuilding. recovery were enabled by the concerted efforts of a myriad of actors operating from different tracks but with a common goal to Other subjects in the series include: end the war. The actions of these actors and stakeholders (both Civil society views on next indigenous and foreign) broadly involved a variety of generation peacebuilding and peacemaking, peacekeeping and peacebuilding activities that were conflict prevention policy and programming * implemented at local, national, sub-regional, continental and/or Environmental and natural international levels. Among these many actors and actions, the resource cooperation and transformation in post-conflict active and visible engagement of one group in a structured and situations * Trends in targeted initiative immensely contributed to the cessation of peacebuilding in Latin America * Future directions hostilities and initiation of the post-conflict recovery process. -

Implementation of Abuja II Accord and Post-Conflict Security in Liberia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2007-06 Implementation of Abuja II accord and post-conflict security in Liberia Ikomi, Emmanuel Oritsejolomi Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/3440 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS IMPLEMENTATION OF ABUJA II ACCORD AND POST- CONFLICT SECURITY IN LIBERIA by Emmanuel Oritsejolomi Ikomi June 2007 Thesis Advisor: Letitia Lawson Second Reader: Karen Guttieri Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED June 2007 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE Implementation of Abuja II Accord and Post- 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Conflict Security in Liberia 6. AUTHOR Emmanuel Oritsejolomi Ikomi 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. -

Liberia April 2004

LIBERIA COUNTRY REPORT April 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION AND NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Liberia April 2004 CONTENTS 1 Scope of the document 1.1 - 1.7 2 Geography 2.1 3 Economy 3.1 - 3.2 4 History 4.1 - 4.2 5 State Structures The Constitution 5.1 Citizenship 5.2 Political System 5.3 – 5.7 Judiciary 5.8 – 5.11 Legal Rights/Detention 5.12 – 5.13 Death Penalty 5.14 Internal Security 5.15 – 5.23 Border security and relations with neighbouring countries 5.24 – 5.26 Prison and Prison Conditions 5.27 – 5.29 Armed Forces 5.30 – 5.31 Military Service 5.32 Medical Services 5.33 – 5.34 People with disabilities 5.35 Educational System 5.36 – 5.37 6 Human Rights 6A Human Rights Issues Overview 6.1 – 6.3 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.4 – 6.10 Journalists 6.11 – 6.12 Freedom of Religion 6.13 – 6.17 Religious Groups 6.18 – 6.19 Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.20 – 6.22 Employment Rights 6.23 – 6.25 People Trafficking 6.26 Freedom of Movement 6.27 6B Human Rights – Specific Groups Ethnic Groups 6.28 – 6.29 Mandingo 6.30 Krahn 6.31 Women 6.32 – 6.36 Children 6.37 – 6.41 Homosexuals 6.42 6C Human Rights – Other Issues Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) 6.43 – 6.45 United Nations 6.46 – 6.47 Humanitarian situation 6.48 – 6.52 Annex A: Chronology of major events Annex B: Political Organisations Annex C: Prominent People Annex D: List of Source Material Liberia April 2004 1. -

Liberia 2005: an Unusual African Post-Conflict Election

J. of Modern African Studies, 44, 3 (2006), pp. 375–395. f 2006 Cambridge University Press doi:10.1017/S0022278X06001819 Printed in the United Kingdom Liberia 2005: an unusual African post-con£ict election David Harris* ABSTRACT The 2003 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) and the ensuing two-year- long National Transitional Government of Liberia (NTGL), which brought together two rebel forces, the former government and members of civil society, justifiably had many critics but also one positive and possibly redeeming feature. In spite of, or perhaps because of, the realpolitik nature of the CPA and the barely disguised gross corruption of the members of the coalition government, the protagonists in the second Liberian civil war (2000–03) complied with the agreement and the peace process held. The culmination of this sequence of events was the 11 October 2005 national elections, the 8 November presidential run-off and the 16 January 2006 inauguration. In several ways, this was the African post-conflict election that broke the mould, but not just in that a woman, Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf, won the presidential race, and a football star, George Weah, came second. The virtual absence of transformed rebel forces or an overbearing incumbent in the electoral races, partially as a result of the CPA and NTGL, gave these polls extraordinary features in an African setting. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND After fifteen years of post-Cold War post-conflict African elections, it can now be said that some patterns are emerging, except that Liberia appears to have upset one or two of these rhythms. In some ways, the 2005 Liberian polls emerged firmly against general African electoral precedents – including those of the 1997 Liberian election, which ushered in the rule of the former ‘warlord’, Charles Taylor (Harris 1999). -

A Sub-National Case Study of Liberal Peacebuilding in Sierra Leone and Liberia

Department of Political Science McGill University Harmonizing Customary Justice with the Rule of Law? A Sub-national Case Study of Liberal Peacebuilding in Sierra Leone and Liberia By Mohamed Sesay A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) Mohamed Sesay, 2016 ABSTRACT One of the greatest conundrums facing postwar reconstruction in non-Western countries is the resilience of customary justice systems whose procedural and substantive norms are often inconsistent with international standards. Also, there are concerns that subjecting customary systems to formal regulation may undermine vital conflict resolution mechanisms in these war-torn societies. However, this case study of peacebuilding in Sierra Leone and Liberia finds that primary justice systems interact in complex ways that are both mutually reinforcing and undermining, depending on the particular configuration of institutions, norms, and power in the local sub-national context. In any scenario of formal and informal justice interaction (be it conflictual or cooperative), it matters whether the state justice system is able to deliver accessible, affordable, and credible justice to local populations and whether justice norms are in line with people’s conflict resolution needs, priorities, and expectations. Yet, such interaction between justice institutions and norms is mediated by underlying power dynamics relating to local political authority and access to local resources. These findings were drawn from a six-month fieldwork that included collection of documentary evidence, observation of customary courts, and in-depth interviews with a wide range of stakeholders such as judicial officials, paralegals, traditional authorities, as well as local residents who seek justice in multiple forums. -

Taylor Trial Transcript

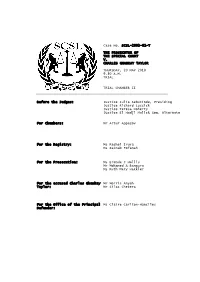

Case No. SCSL-2003-01-T THE PROSECUTOR OF THE SPECIAL COURT V. CHARLES GHANKAY TAYLOR THURSDAY, 20 MAY 2010 9.30 A.M. TRIAL TRIAL CHAMBER II Before the Judges: Justice Julia Sebutinde, Presiding Justice Richard Lussick Justice Teresa Doherty Justice El Hadji Malick Sow, Alternate For Chambers: Mr Artur Appazov For the Registry: Ms Rachel Irura Ms Zainab Fofanah For the Prosecution: Ms Brenda J Hollis Mr Mohamed A Bangura Ms Ruth Mary Hackler For the accused Charles Ghankay Mr Morris Anyah Taylor: Mr Silas Chekera For the Office of the Principal Ms Claire Carlton-Hanciles Defender: CHARLES TAYLOR Page 41302 20 MAY 2010 OPEN SESSION 1 Thursday, 20 May 2010 2 [Open session] 3 [The accused present] 4 [Upon commencing at 9.30 a.m.] 09:32:34 5 PRESIDING JUDGE: Good morning. We'll take appearances 6 first, please. 7 MS HOLLIS: Good morning, Madam President, your Honours, 8 opposing counsel. This morning for the Prosecution, Mohamed A 9 Bangura, Ruth Mary Hackler and Brenda J Hollis. 09:33:02 10 MR ANYAH: Good morning, Madam President. Good morning, 11 your Honours. Good morning, counsel opposite. Appearing for the 12 Defence this morning are myself, Morris Anyah, Mr Silas Chekera. 13 We are joined by our legal assistant Mr Simon Chapman. There is 14 a new face with us in court for the first time today. He is an 09:33:26 15 intern in our office. His name is Neelan Tharmaratnam. 16 Mr Tharmaratnam is studying public international law at Leiden 17 University. 18 Last, and certainly not the least, we are joined by the 19 Principal Defender of the Special Court, Ms Claire 09:33:56 20 Carlton-Hanciles, and we welcome her back to the Court. -

Situation Report

Institute for Security Studies Situation Report Date issued: 5 October 2010 Author: Lansana Gberie Distribution: General Contact: [email protected] Liberia: The 2011 elections and building peace in the fragile state1 Abstract Liberia holds its second post-war presidential and legislative elections in October 2011. The first, held in 2005, was a landmark: it was the first free and fair elections in the country’s long history (Liberia became a republic in 1847), and it ushered in Africa’s first elected female president. Since then Liberia, previously wracked by bloody petty wars, has been largely stable, though very fragile. The 2011 elections will probably be just as important as the one in 2005. Their successful conduct will determine when the UN, which still maintains about 8 000 troops in the country, will finally withdraw. No doubt, the outcome of the polls will also determine whether the country maintains the promising trajectory it has had since 2006. And success will be measured from both the conduct of the elections and the results of the polls: the polls will have to be conducted in a free and fair atmosphere for the results to be broadly acceptable; but who emerges as president will be just as important. The current president, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, has been progressive and reform-minded, and she commands wide support from donors and international investors: in less than a year of her election, Liberia’s image as a failed and almost criminal state exporting violence to its neighbours changed dramatically. Whatever the outcome of the elections, however, it is important that international players – primarily ECOWAS, AU and UN – maintain a steady focus on the three areas that the Liberian government has identified as critical to sustained peace building: security sector rebuilding, the administration of justice, and national reconciliation and healing.