Pohl Istephanous 2020.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Distribución Y Uso Tradicional De Sagittaria Macrophylla Zucc. Y S

Ciencia Ergo Sum ISSN: 1405-0269 [email protected] Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México México Zepeda Gómez, Carmen; Lot, Antonio Distribución y uso tradicional de Sagittaria macrophylla Zucc. y S. latifolia Willd. en el Estado de México Ciencia Ergo Sum, vol. 12, núm. 3, noviembre-febrero, 2005, pp. 282-290 Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México Toluca, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=10412308 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto C IENCIAS NATURALES Y AGROPECUARIAS Distribución y uso tradicional de Sagittaria macrophylla Zucc. y S. latifolia Willd. en el Estado de México Carmen Zepeda Gómez* y Antonio Lot** Recepción: 3 de noviembre de 2004 Aceptación: 26 de mayo de 2005 * Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Autónoma Resumen. Sagittaria macrophylla y S. latifolia Distribution and Traditional Usage of del Estado de México. son plantas acuáticas emergentes que crecen Sagittaria macrophylla Zucc. and S. Correo electrónico: [email protected] ** Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional en las orillas y zonas poco profundas de los latifolia Willd. in the State of Mexico Autónoma de México. cuerpos de agua limpios y de poca corriente. Abstract. Sagittaria macrophylla and S. latifolia Correo electrónico: [email protected] La primera es endémica de México, su are emergent aquatic plants which grow along Agradecemos a la Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México por el financiamiento para distribución se restringe a la región del río the shorelines in clean shallow pools with realizar esta investigación (clave 1669/2003), al Lerma y valle de México y está en peligro de slow moving water. -

Aquatic Vascular Plant Species Distribution Maps

Appendix 11.5.1: Aquatic Vascular Plant Species Distribution Maps These distribution maps are for 116 aquatic vascular macrophyte species (Table 1). Aquatic designation follows habitat descriptions in Haines and Vining (1998), and includes submergent, floating and some emergent species. See Appendix 11.4 for list of species. Also included in Appendix 11.4 is the number of HUC-10 watersheds from which each taxon has been recorded, and the county-level distributions. Data are from nine sources, as compiled in the MABP database (plus a few additional records derived from ancilliary information contained in reports from two fisheries surveys in the Upper St. John basin organized by The Nature Conservancy). With the exception of the University of Maine herbarium records, most locations represent point samples (coordinates were provided in data sources or derived by MABP from site descriptions in data sources). The herbarium data are identified only to township. In the species distribution maps, town-level records are indicated by center-points (centroids). Figure 1 on this page shows as polygons the towns where taxon records are identified only at the town level. Data Sources: MABP ID MABP DataSet Name Provider 7 Rare taxa from MNAP lake plant surveys D. Cameron, MNAP 8 Lake plant surveys D. Cameron, MNAP 35 Acadia National Park plant survey C. Greene et al. 63 Lake plant surveys A. Dieffenbacher-Krall 71 Natural Heritage Database (rare plants) MNAP 91 University of Maine herbarium database C. Campbell 183 Natural Heritage Database (delisted species) MNAP 194 Rapid bioassessment surveys D. Cameron, MNAP 207 Invasive aquatic plant records MDEP Maps are in alphabetical order by species name. -

Ships of 8 Tree Species in Navajo National Monument, Arizona

Population Dynamics and Age Relation- ships of 8 Tree Species in Navajo National Monument, Arizona J.D. BROTHERSON, S.R. RUSHFORTH, W.E. EVENSON, J.R. JOHANSEN, AND C. MORDEN The presence of 3 major archeological ruins dating from the 1 lth cent slickrock areas and the plateau behind the canyon rim to 13th centuries (Woodbury 1963) provided the primary motiva- (Brotherson et al. 1978). The pigmy woodland community covers tion for including Navajo National Monument in the National more area than any other type in northeastern Arizona. Parks System. Also included in the monument are some unique Gambel oak is the most extensive type in the Monument aside ecosystems, especially a small relict of “mountain vegetation” from tne pinyon-juniper community. It is found inall 3 segments of found in Betatakin Canyon. As visitor pressures mount annually, the monument but reaches its greatest development at Keet Steel proper management of these unique ecosystems becomes highly and Betatakin. Pnrnus emarginata (bittercherry) also grows at important. Since trees are the dominant features of these ecosys- Keet Steel but is uncommon. tems, and are central to management considerations, the present The streamside community of the Inscription House segment of work has examined populations of 8 major tree species in the the monument contains Popufus fremontii (Fremont poplar), monument. Populus angustifolia (narrowleaf cottonwood), Salk goodingii The objectives of this study were, first, to develop age prediction (Gooding willow), Tamarix ramosissima (salt cedar), and Elaeg- equations for tree species growing in Navajo National Monument, nus angustifolia (Russian olive). Fremont poplar is the dominant and second, to assess the present age profiles, reproductive recruit- tree within this community with salt cedar attaining local impor- ment, and density relationships of these tree populations. -

C P the Important Distinctions

C P The Important Distinctions S Common M Pin Cherry Black Cherry Chokecherry Canada Plum Prunus pennsylvanica Prunus serotina Prunus nigra U Prunus virginiana L P BARK D Smooth with a pungent, Young trunks: prominent N Nearly smooth. Large disagreeable odor. white lenticals. TEXTURE horizontal lenticels show Lenticels less prominent Lenticels yellowish A Older trunks: fissured orange when rubbed. than on other and ridged. Prunus species. S E Grayish-brown, with I COLOR Reddish-brown Young trunks are black Dull reddish-brown to black light-colored fissures R LEAVES R E Elliptic/oblong, widest in H Long and tapering from the center, thick leathery Obovate, widest in the C base to tip. Widest in the and shiny. Underside of terminal 1⁄3, sharply saw- Ovate or obovate tapering GENERAL lower 1⁄3; thin and firm midrib near stalk end cov- toothed and without hairs, abruptly into a long thin DESCRIP- textured with round teeth. ered with rusty, brown medium leathery in tex- point. Teeth rounded. TION Glands on stalk, and no hairs. Glands on stalk ture, glands on stalk and Glands on stalk. hairs on midribs. near blade. Margin has no brown hairs on midrib. rounded teeth. TWIGS Thorns common on SHAPE Very fine Waxy Medium slender older twigs Red-brown with a lighter Current growth gray, older COLOR Red and reddish-brown Gray or purplish-brown or greenish margin growth darkening to black Sharp, pungent smell Strong, pungent bitter- ODOR Slight cherry odor None when broken almond odor BUDS Cone shaped, slender – Football-shaped with a SHAPE Ovate, -

TREES for WESTERN NEBRASKA Justin Evertson & Bob Henrickson

THE NEBRASKA STATEWIDE ARBORETUM PRESENTS TREES FOR WESTERN NEBRASKA Justin Evertson & Bob Henrickson. For more plant information, visit plantnebraska.org or retreenbraska.unl.edu The following species are recommended for areas in the western half of Nebraska and/or typically receive less than 20” of moisture per year. Size Range: The size range indicated for each plant is the expected average mature height x spread for Nebraska. Large Deciduous Trees (typically over 40 feet tall at maturity) NOTE ON ASH SPECIES: Native American ash trees are being decimated by Emerald Ash Borer (EAB) and the insect is now in Nebraska. NSA recommends that native ash species no longer be planted in Nebraska. 1. Ash, Manchurian - Fraxinus mandshurica (from Asia; upright growth; drought tolerant; may be resistant to EAB; 40’x 30’) 2. Catalpa, Northern - Catalpa speciosa (native; tough tree; large, heart-shaped leaves, showy flowers and long seed pods; 50’x 35’) 3. Coffeetree, Kentucky - Gymnocladus dioicus (native; amazingly adaptable; beautiful winter form; 50’x 40’) 4. Cottonwood, Eastern - Populus deltoides (majestic native; not for extremely dry sites; avoid most cultivars; 80’x 60’) 5. Cottonwood, Lanceleaf - Populus acuminata (native; naturally occurring hybrid; narrow leaves; for west. G.P.; 50’x 35’) 6. Elm, American - Ulums americana (disease resistant varieties include ‘Valley Forge’ and ‘New Harmony’; 50’x50’) 7. Elm, Japanese - Ulmus davidiana var. japonica (cold tolerant; rounded; glossy green; ‘Discovery’ is a cultivar from Manitoba Canada; 45’x 45’) 8. Elm, Rock - Ulmus thomasii (distinctive corky stems; upright habit; DED resistance in west; 50-60’x 30-40’) New Elm, Hybrids - many disease resistant hybrid elms have been developed and show promise, including: 9. -

Chokecherry Prunus Virginiana L

chokecherry Prunus virginiana L. Synonyms: Prunus virginiana ssp. demissa (Nutt.) Roy L. Taylor & MacBryde, P. demissa (Nutt.) Walp. Other common names: black chokecherry, bitter-berry, cabinet cherry, California chokecherry, caupulin, chuckleyplum, common chokecherry, eastern chokecherry, jamcherry, red chokecherry, rum chokecherry, sloe tree, Virginia chokecherry, western chokecherry, whiskey chokecherry, wild blackcherry, wild cherry Family: Rosaceae Invasiveness Rank: 74 The invasiveness rank is calculated based on a species’ ecological impacts, biological attributes, distribution, and response to control measures. The ranks are scaled from 0 to 100, with 0 representing a plant that poses no threat to native ecosystems and 100 representing a plant that poses a major threat to native ecosystems. Description Similar species: Several non-native Prunus species can Chokecherry is a deciduous, thicket-forming, erect shrub be confused with chokecherry in Alaska. Unlike or small tree that grows 1 to 6 m tall from an extensive chokecherry, which has glabrous inner surfaces of the network of lateral roots. Roots can extend more than 10 basal sections of the flowers, European bird cherry m horizontally and 2 m vertically. Young twigs are often (Prunus padus) has hairy inner surfaces of the basal hairy. Stems are numerous, slender, and branched. Bark sections of the flowers. Chokecherry can also be is smooth to fine-scaly and red-brown to grey-brown. differentiated from European bird cherry by its foliage, Leaves are alternate, elliptic to ovate, and 3 to 10 cm which turns red in late summer and fall; the leaves of long with pointed tips and toothed margins. Upper European bird cherry remain green throughout the surfaces are green and glabrous, and lower surfaces are summer. -

Native Shrubs

Native Shrubs Downy Serviceberry (Amelanchier arborea) Grows from 10 to 25 feet high with a spread of 12 feet. A deciduous tree that prefers rich loamy soil but will grow well in clay or any soil that has moderate moisture. White showy flowers bloom in early to mid spring and are followed by dark red to purple edible berries. Zones 4 - 9. Shadblow Serviceberry (Amelanchier canadensis) Grows from 25 to 30 feet high with a spread of 15 to 20 feet. Grows best in medium wet, well-drained soil but will tolerate a wide range. Prefers partial shade to full sun. Clusters of white flowers are followed by edible red/purple berries in late summer. Zones 4-8 Allegheny Serviceberry (Amelancheir laevis) Grows to approximately 25 feet high with a spread of 20 feet. Grows in shade and partial shade and prefers moist soils. A hardy serviceberry species that will tolerate more moisture and light then some other varieties. White flowers and purple/black edible berries are typical. Zones 4-8. Bog Rosemary (Andromeda polifolia) Grows from 6 to 30 inches high with a spread of 3 feet. Leaves are narrow, evergreen and leathery with a blue-green color. Some resemblance to the culinary herb. Typically found in northern bogs and marshes. Flowers are small, pink, and bell- shaped. Grows best in very moist, acidic soil in cooler climates. Zones 2- 6. Black Chokeberry (Aronia melancarpa) Can grow up to 8 feet high with a spread of 8 feet. Grows best in moist, well-drained, acidic soils but will tolerate drier sandy soils or wet clayey ones. -

Pickerel-Weed – Arrow-Arum – Arrowhead Emergent Wetland

Pickerel-weed – Arrow-arum – Arrowhead Emergent Wetland System: Palustrine Subsystem: Non-persistent PA Ecological Group(s): Emergent Wetland and Marsh Wetland Global Rank: GNR State Rank: S4 General Description This community type is dominated by broad-leafed, emergent vegetation; it occurs in upland depressions, borders of lakes, large slow-moving rivers, and shallow ponds. The aspect of these systems changes seasonally from nearly unvegetated substrate in winter and early spring, when plants are dormant, to dense vegetation during the height of the growing season. The most characteristic species are pickerel-weed (Pontederia cordata), arrow-arum (Peltandra virginica), and wapato (Sagittaria latifolia). Other species commonly present include showy bur-marigold (Bidens laevis), mannagrass (Glyceria spp.), goldenclub (Orontium aquaticum), bur-reed (Sparganium spp), arrowhead (Sagittaria rigida), soft-stem bulrush (Schoenoplectus tabernaemontani), spike-rush (Eleocharis palustris), false water-pepper (Persicaria hydropiperoides), water-pepper (Persicaria punctata), water smartweed (Persicaria amphibia), jewelweed (Impatiens spp.), common bladderwort (Utricularia macrorhiza), duckweed (Lemna minor), water-meal (Wolffia spp.), and broad-leaved water-plantain (Alisma subcordatum). This community is often interweaved with aquatic beds on the deep side, and shallower marsh or swamp communities on the shore side, and thus species characteristic of those communities are often present. This type is restricted to shallow (less than 2 meters at low -

Bird Communities of Gambel Oak: a Descriptive Analysis

United States Department of Agriculture Bird Communities Forest Service Rocky Mountain of Gambel Oak: A Research Station General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-48 Descriptive Analysis March 2000 Andreas Leidolf Michael L. Wolfe Rosemary L. Pendleton Abstract Leidolf, Andreas; Wolfe, Michael L.; Pendleton, Rosemary L. 2000. Bird communities of gambel oak: a descriptive analysis. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-48. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 30 p. Gambel oak (Quercus gambelii Nutt.) covers 3.75 million hectares (9.3 million acres) of the western United States. This report synthesizes current knowledge on the composition, structure, and habitat relationships of gambel oak avian communities. It lists life history attributes of 183 bird species documented from gambel oak habitats of the western United States. Structural habitat attributes important to bird-habitat relationships are identified, based on 12 independent studies. This report also highlights species of special concern, provides recommendations for monitoring, and gives suggestions for management and future research. Keywords: Avian ecology, bird-habitat relationships, neotropical migrant, oakbrush, oak woodlands, scrub oak, Quercus gambelii, Western United States The Authors ______________________________________ Andreas Leidolf is a Graduate Research Assistant in the Department of Fisheries and Wildlife at Utah State University (USU). He received a B.S. degree in Forestry/Wildlife Management from Mississippi State University in 1995. He is currently completing his M.S. degree in Fisheries and Wildlife ecology at USU. Michael L. Wolfe is a Professor in the Department of Fisheries and Wildlife at USU. He received a B.S. degree in Wildlife Management at Cornell University in 1963 and his doctorate in Forestry/Wildlife Management at the University of Göttingen, Germany, in 1967. -

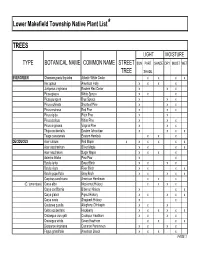

Native Plant List Trees.XLS

Lower Makefield Township Native Plant List* TREES LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE EVERGREEN Chamaecyparis thyoides Atlantic White Cedar x x x x IIex opaca American Holly x x x x Juniperus virginiana Eastern Red Cedar x x x Picea glauca White Spruce x x x Picea pungens Blue Spruce x x x Pinus echinata Shortleaf Pine x x x Pinus resinosa Red Pine x x x Pinus rigida Pitch Pine x x Pinus strobus White Pine x x x Pinus virginiana Virginia Pine x x x Thuja occidentalis Eastern Arborvitae x x x x Tsuga canadensis Eastern Hemlock xx x DECIDUOUS Acer rubrum Red Maple x x x x x x Acer saccharinum Silver Maple x x x x Acer saccharum Sugar Maple x x x x Asimina triloba Paw-Paw x x Betula lenta Sweet Birch x x x x Betula nigra River Birch x x x x Betula populifolia Gray Birch x x x x x Carpinus caroliniana American Hornbeam x x x (C. tomentosa) Carya alba Mockernut Hickory x x x x Carya cordiformis Bitternut Hickory x x x Carya glabra Pignut Hickory x x x x x Carya ovata Shagbark Hickory x x Castanea pumila Allegheny Chinkapin xx x Celtis occidentalis Hackberry x x x x x x Crataegus crus-galli Cockspur Hawthorn x x x x Crataegus viridis Green Hawthorn x x x x Diospyros virginiana Common Persimmon x x x x Fagus grandifolia American Beech x x x x PAGE 1 Exhibit 1 TREES (cont'd) LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE DECIDUOUS (cont'd) Fraxinus americana White Ash x x x x Fraxinus pennsylvanica Green Ash x x x x x Gleditsia triacanthos v. -

Reommended Trees for Colo Front Range Communities.Pmd

Recommended Trees for Colorado Front Range Communities A Guide for Selecting, Planting, and Caring For Trees Do Not Top Your Trees! http://csfs.colostate.edu www.coloradotrees.org Trees that have been topped may become hazardous and unsightly. Avoid topping trees. Topping leads to: • Starvation www.fs.fed.us • Shock • Insects and diseases • Weak limbs • Rapid new growth • Tree death • Ugliness Special thanks to the International Society of Arboriculture for • Increased maintenance costs providing details and drawings for this brochure. Eastern redcedar* (Juniperus virginiana) Tree Selection Very hardy tree, excellent windbreak tree, green summer foliage, rusty brown in the winter Tree selection is one of the most important investment decisions a home owner makes when landscaping a new home or replacing a Rocky Mountain juniper* (Juniperus scopulorum) tree lost to damage or disease. Most trees can outlive the people Very hardy tree, excellent windbreak tree who plant them, therefore the impact of this decision is one that can influence a lifetime. Matching the tree to the site is critical; the following site and tree demands should be considered before buying and planting a tree. Trees to avoid! Site Considerations Selecting the right tree for the right place can help reduce the potential • Available space above and below ground for catastrophic loss of trees by insects, disease or environmental factors. We can’t control the weather, but we can use discernment in • Water availability selecting trees to plant. A variety of tree species should be planted so no • Drainage single species represents more than 10-15 percent of a community’s • Soil texture and pH total tree population. -

Trees to Avoid Planting in the Midwest and Some Excellent Alternatives

Trees to Avoid Planting in the Midwest and Some Excellent Alternatives Dr. Laura G. Jull Dept. of Horticulture, UW-Madison Trees provide us with many environmental, aesthetic, functional, and economic benefits. Tree selection is one of the most important considerations when a homeowner, nurserymen, or landscaper is deciding what species to grow or plant. Many questions need to be answered including size, location, site characteristics, aesthetic features, pest susceptibility, hardiness, and maintenance considerations. Some trees can become a maintenance headache due to their inherent pest problems or lack of structural integrity. The trees represented in this story have not generally performed well in urban and suburban areas of the Midwest. Some are susceptible to insects and diseases, and some have severe structural problems such as being weak- wooded or prone to girdling roots or included bark formation. Others have cultural problems such as intolerance to high pH, road salt, drought, and poor drainage. A few tree species are invasive and should be avoided near sensitive areas or seed dispersal into woodlands could occur. Some of these trees may do quite well in other parts of the U.S., so my intention is not to apply a blanket statement for all these trees to all situations. Invasiveness and pest susceptibility can vary geographically. The article is based on more than 25 years of field experience and data collected from numerous states’ plant disease and insect diagnostic clinics, and conversations with arborists, nurseries, landscapers, and extension personnel. There are alternative species that can be used and are mentioned here. These alternative tree species have performed well in USDA Cold Hardiness Zone 4b.