WRI) in Close Collaboration with the USAID-Funded Coral Triangle Support Partnership (CTSP)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COASTAL CAPITAL Ecosystem Valuation for Decision Making in the Caribbean

COASTAL CAPITAL Ecosystem Valuation for Decision Making in the Caribbean RICHARD WAITE, LAURETTA BURKE, AND ERIN GRAY Photo: Katina Rogers Coastal Capital – Studies 2005-11 Coastal Capital – Studies 2005-11 Lower $, but important for food/jobs High $ High $ Photos: Crispin Zeenam (fisherman), Steve Linfield (wave break), K. Tkachenko (diving) Coastal Capital – Impacts? Main research questions • Which valuation studies have informed decision making in the Caribbean? • What made those studies successful in informing decision making? Use of coastal ecosystem valuation in decision making in the Caribbean • Low observed use so far • But, 20+ case studies offer lots of lessons Valuation supports MPA establishment St. Maarten, Haiti, Cuba, Bahamas, USA Photo: Tadzio Bervoets Valuation supports establishment of entry fees Bonaire, Dominican Republic, Mexico, Belize, St. Eustatius Image: STINAPA Valuation supports damage claims Belize, Jamaica, St. Eustatius, St. Maarten Source: U.S. Coast Guard. Valuation informs marine spatial planning Belize Source: Clarke et al. (2013). How else have valuation results been used? • Justify other policy changes (e.g., fishing regulations, offshore oil drilling ban) • Justify investment in management/conservation/ enforcement • Design Payments for Ecosystem Services schemes • Raise awareness/highlight economic importance Photo: Lauretta Burke Valuation results have informed decision making across the Caribbean Note: Not exhaustive. Why were these 20+ studies influential? …enabling conditions for use in decision -

The Ecology and Economy of Coral Reefs: Considerations in Marketing Sustainability

The Ecology and Economy of Coral Reefs: Considerations in Marketing Sustainability Rick MacPherson Director, Conservation Programs Coral Reef Alliance Coral Reefs in Peril: Worldwide Status •2004: 70% of coral reefs “are under imminent risk of collapse through human pressures,” or “are under a longer term threat of collapse.” (Up from 58% in 2002.) RED = high risk YELLOW = medium risk BLUE = low risk Almost two-thirds of Caribbean reefs are threatened 3 RED = high risk YELLOW = medium risk BLUE = low risk Science says: • Climate Change and CO2: bleaching and acidification • Local threats undermine reef resilience to climate change • MMAs lack resources and community support • 50% of reefs could be destroyed by 2050 Coral Reefs in Peril: Regional Status •Caribbean reefs have suffered an 80% decline in cover during the past three decades. •80 to 90% of elkhorn and staghorn coral is gone. •Currently, coastal development threatens 33% of the reefs, land- based sources of pollution 35%, and over-fishing more than 60%. 5 Why Should You Care? CoralCoral reefsreefs provideprovide vitalvital ““ecosystemecosystem servicesservices”” 6 The Importance of Coral Reefs: Biodiversity • Only a very tiny portion of the sea bottom is covered by coral reefs (0.09%) with a total area about the size of Arizona or the UK • Yet, they’re home or nursery ground for 25% of all known marine species and (probably over one million species). 7 Biodiversity 8 The Importance of Coral Reefs: Medicine • 50% of current cancer medication research focuses on marine organisms found on coral reefs. 9 Importance of Coral Reefs: Food •Coral reefs worldwide yield a total value of over US$100 billion per year from food alone •Primary source of protein for over 1 billion people Constanza et al. -

Tribal Weaving of the Lesser Sunda Islands

TRIBAL WEAVING OF THE LESSER SUNDA ISLANDS The diverse Lesser Sunda Islands, stretching eastwards from Bali, offer the most amazing landscapes and a glorious cornucopia of weaving for textile lovers. Here women not only continue to make their traditional cloth on back-tension looms but continue to wear it as well. There is kaleidoscopic variety of patterns and designs – every region of every island has its own unique textile culture, its own style of dress, and its own motifs. Together we will explore the extraordinary ancestral traditions of these islands where textiles are the predominant form of artistic expression, still playing a central role in every significant stage of life, especially marriage and death. Some islanders tell us, “Without cloth we cannot marry.” However, change is underway series of evening talks. Please Note: The price of this cruise in even the remotest villages, and weavers are no longer does not include any domestic airfares to and from our start passing on their skills to the next generation. With this cruise, and end points. If you are booking by yourself, please check we will be given a unique opportunity to witness a dying art form with us first to find out the best routes to take, and to ensure before it is gone forever. We will enjoy the luxury of cruising that you arrive at your destination with plenty of time to spare. effortlessly from island to island, crossing a rugged, isolated Except for Bali, transfers to and from local airports to the boat region where travel by land can be difficult. -

State of the Coral Triangle: Solomon Islands

State of the Coral Triangle: Solomon Islands One of a series of six reports on the status of marine resources in the western Pacific Ocean, the State of the Coral Triangle: Solomon Islands describes the biophysical characteristics of Solomon Islands’ coastal and marine ecosystems, the manner in which they are being exploited, the framework in place that governs their use, the socioeconomic characteristics of the communities that use them, and the environmental threats posed by the manner in which STATE OF THE CORAL TRIANGLE: they are being used. It explains the country’s national plan of action to address these threats and improve marine resource management. Solomon Islands About the Asian Development Bank ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to approximately two-thirds of the world’s poor: 1.6 billion people who live on less than $2 a day, with 733 million struggling on less than $1.25 a day. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by 67 members, including 48 from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines www.adb.org Printed on recycled paper Printed in the Philippines STATE OF THE CORAL TRIANGLE: Solomon Islands © 2014 Asian Development Bank All rights reserved. -

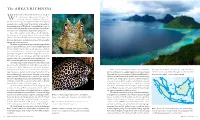

The AREA's RICHNESS

The AREA’S RICHNESS hile there is little doubt that the Coral Triangle is the richest marine environment on the planet, the reasons for the richness are hotly debated. Is it because Wthe richest taxonomic groups originated in the Coral Triangle and dispersed to the rest of the world? Or is it because of the overlap of flora and fauna from the West Pacific Ocean and Indian Ocean? As it turns out, the only thing that is clear is that the reasons for the area’s richness are complex and no single model explains it all. Some of the many factors that influence the diversity of the Coral Triangle are the geological history of the region, including plate tectonics and sea-level fluctuations; how species disperse and the factors that facilitate or inhibit dispersal; general biogeographic patterns and evolutionary forces. The tropics are generally more species rich than temperate and polar areas particularly because of the constant sunlight regime and weather stability. Without a winter period, organisms can flourish year round and put more energy into specialization than into preparing for long periods with reduced sunlight. This is as true in the marine realm as it is in the forests, where light and relatively constant warm water temperatures persist throughout the year. However, coastal tropical waters are relatively nutrient poor. The annual changes in water temperatures of the temperate and polar seas produce mixing when the surface waters cool and sink to the bottom. The displaced bottom waters, rich with dead plankton that has sank to the depths, are forced to the surface and result in Due to ocean circulation patterns and the rotation of the Earth, As the glaciers melted and sea levels rose, the newly evolved species huge explosions of zooplankton and fish populations. -

The Coral Reef Alliance • 2010 Annual Report INDIVIDUALLY, WE ARE ONE DROP

THE CORAL reef alliance • 2010 ANNUAL REPORT INDIVIDUALLY, WE ARE ONE DROP. TOGETHER, WE ARE AN OCEAN. -Ryunosuke Satoro, Poet 3 From the Executive Director From the Board Chair Forging new partnerships to save coral As a businessman and entrepreneur, I reefs is part of our DNA here at the Coral became involved with CORAL because Reef Alliance (CORAL). And looking back on I was impressed by their unique—and 2010, it’s through that quintessentially CORAL proven—strategy of improving reef health by approach that we addressed challenges and developing and implementing sustainable change. World headlines last year captured community-based solutions. As board chair, news of mass coral bleaching in Southeast Asia, Micronesia, I have realized an even deeper appreciation for the organization and the Caribbean, underscoring the urgency of our work. as I have worked more closely with CORAL’s talented team and Instead of getting mired in the gloomy news, CORAL expanded witnessed their unwavering commitment to our mission. our effective reef conservation strategies by cultivating key partnerships, including an exciting new collaboration with the Over the last year, the board of directors has been working Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. diligently to move the organization forward. While we said farewell to some long-time members, we also welcomed a We know that we have a narrow window of time to affect positive stellar new addition—Dr. Nancy Knowlton, Sant Chair for change for coral reefs. With that in mind, we are embarking on Marine Science at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of new projects that will dramatically extend our impact. -

The Trade in Live Reef Food Fish Volume 1

THE TRADE IN LIVE REEF FOOD FISH GOING GOING GONE VOLUME 1 MAIN REPORT Acknowledgements This report was prepared by ADM Capital Foundation and the University of Hong Kong. We would like to thank Sam Inglis, Lisa Genasci, Jane Chu, Kathleen Ho and and Ellie Appleby for their diligence in reading and editing; Doug Woodring, who drove the initial concept; and DESIGNORM for their innovative and informative graphics. Rachel Wong helped to compile some of the data, and Liu Min, Joyce Wu and Felix Chan kindly provided data. We are grateful to the government staff of the Marine Department, the Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department, the Fish Marketing Organization and the Customs and Excise Department for responding to our questions and clarifying issues raised, as well as reviewing an earlier draft, and to the many traders and participants of the trade who we interviewed. Disclaimer This document (the ‘Document’) has been prepared by ADM Capital Foundation (‘ADMCF’) for general introduction, overview and discussion purposes only and does not constitute definitive advice on regulatory, investment or legal issues. It should not be used as a substitute for taking regulatory, financial, tax or legal advice in any specific situation. Information provided in the report has been obtained from, or is based upon, sources believed to be reliable but have not been independently verified, and no guarantee, representation or warranty is made as to its accuracy or completeness. Information contained in this Document is current as of December 2017 and is subject to change without notice. Information contained in this Document relating to unrealised data and projections is indicative only, and has been based on unaudited, internal data and assumptions, which have not been independently verified and are subject to material corrections, verifications and amendments. -

World Watch Report

CONFIDENTIAL WORLD WATCH® REPORT ON Indonesia Date: 07/02/2018 21:18:40 GMT / UTC UnitedHealthcare Global Risk | 2925 Briarpark Drive, 11th Floor | Houston, Texas 77042 | ph: (713) 4307300 | email: [email protected] | url: www.uhcglobal.com World Watch® is confidential and is intended solely for the information and use of UnitedHealthcare Global's clients. Given the nature of the information, UnitedHealthcare Global does not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the information because agencies outside the control of UnitedHealthcare Global contribute information to World Watch®. While UnitedHealthcare Global vets and verifies all information with the utmost care and consideration for the end user, UnitedHealthcare Global does not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the information and specifically disclaims all responsibility for any liability, loss or risk, personal or otherwise, which is incurred as a consequence, directly or indirectly, of the use and application of, or reliance upon, any of the information on this site, including customized reports created by clients. Any alteration or modification of the content of World Watch®, either from the website or via printed reports, is strictly prohibited. For more information, please contact us at [email protected] or visit www.uhcglobal.com. Copyright © 2018 UnitedHealthcare Global. All rights reserved. For Terms and Conditions go to Terms Of Use World Watch® Report from UnitedHealthcare Global Indonesia Executive Summary for Indonesia An ethnically and linguistically diverse country, Indonesia consists of 17,000 islands spanning across the Indian and Pacific oceans. The islands, which are generally grouped by region, include the Sumatra Islands, Kalimantan/Borneo Island, Java Island, Bali Island, Sulawesi Islands, Nusa Tenggara/Lesser Sunda Islands, Maluku/Spice Islands and Papua. -

Review of the Benefits of No-Take Zones

1 Preface This report was commissioned by the Wildlife Conservation Society to support a three-year project aimed at expanding the area of no-take, or replenishment, zones to at least 10% of the territorial sea of Belize by the end of 2015. It is clear from ongoing efforts to expand Belize’s no-take zones that securing support for additional fishery closures requires demonstrating to fishers and other stakeholders that such closures offer clear and specific benefits to fisheries – and to fishers. Thus, an important component of the national expansion project has been to prepare a synthesis report of the performance of no-take zones, in Belize and elsewhere, in replenishing fisheries and conserving biodiversity, with the aim of providing positive examples, elucidating the factors contributing to positive results, and developing scientific arguments and data that can be used to generate and sustain stakeholder support for no-take expansion. To this end, Dr. Craig Dahlgren, a recognized expert in marine protected areas and fisheries management, with broad experience in the Caribbean, including Belize, was contracted to prepare this synthesis report. The project involved an in-depth literature review of no-take areas and a visit to Belize to conduct consultations with staff of the Belize Fisheries Department, marine reserve managers, and fishermen, collect information and national data, and identify local examples of benefits of no-take areas. In November 2013, Dr. Dahlgren presented his preliminary results to the Replenishment Zone Project Steering Committee, and he subsequently incorporated feedback received from Steering Committee members and WCS staff in this final report. -

How Airlines Can Support Sustainable Trade in Live Reef Food Fish Contents

MOSTLY LEGAL, BUT NOT SUSTAINABLE HOW AIRLINES CAN SUPPORT SUSTAINABLE TRADE IN LIVE REEF FOOD FISH CONTENTS Background: Live Reef Food Fish (LRFFT) – 1 part of the international trade in wildlife .......................................1 2 Hong Kong, a wildlife trade hotspot ..............................................4 Anatomy of the trade ....................................................................8 3 Rising trade volumes Sourced from unregulated and unmanaged fi sheries Trade volumes underestimated Vulnerable groupers are a signifi cant component of the trade A luxury commodity in high demand A low volume high value trade for Hong Kong and the region Impacts and outcomes of the LRFFT ...........................................15 4 Over exploitation threatens species with extinction Expanding the search for fi sh A thriving illegal trade The myth that mariculture will reduce overfi shing Considering food security in source countries A grim outlook The supply chain .........................................................................24 5 A web of players and unequal distribution of benefi ts The aviation industry: part of a bottleneck and part solution A valuable cargo Knowing what you carry is a challenge Risks and CSR considerations .....................................................29 6 A false sense of security amidst increasing scrutiny Reputational Risk Business and Economic risks CSR considerations A time to act – conclusion and recommendations .....................34 7 HKSAR Government Hong Kong International Airport -

Indonesia Cruise – Bali to Flores

Indonesia Cruise – Bali to Flores Trip Summary Immerse yourself in Bali, Komodo Island, and Indonesia's Lesser Sunda Islands from an intimate perspective, sailing through a panorama of islands and encountering new wonders on a daily basis. Explore crystalline bays, tribal villages, jungle-clad mountains, and mysterious lakes on this eight- day long Indonesian small-ship adventure. This exciting adventure runs from Flores to Bali or Bali to Flores depending on the week! (Please call your Adventure Consultant for more details). Itinerary Day 1: Arrive in Bali In the morning we will all meet at the Puri Santrian Hotel in South Bali before boarding our minibus for our destination of Amed in the eastern regency of Karangasem – an exotic royal Balinese kingdom of forests and mighty mountains, emerald rice terraces, mystical water palaces and pretty beaches. With our tour leader providing information along the way, we will stop at Tenganan Village, a community that still holds to the ancient 'Bali Aga' culture with its original traditions, ceremonies and rules of ancient Bali, and its unique village layout and architecture. We’ll also visit the royal water palace of Tirta Gangga, a fabled maze of spine-tinglingy, cold water pools and basins, spouts, tiered pagoda fountains, stone carvings and lush gardens. The final part of our scenic the journey takes us through a magnificent terrain of sculptured rice terraces followed by spectacular views of a fertile plain extending all the way to the coast. Guarded by the mighty volcano, Gunung Agung, your charming beachside hotel welcomes you with warm Balinese hospitality and traditional architecture, rich with hand-carved ornamentation. -

World Bank Document

37741 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 37741 The World Bank Group GEOGRAPHY ECONOMY / SOCIETY 1818 H Street, N. W. Country Of ce Manila Area: Total ..................................... 300,000 sq. km GDP (2005) .................................................. 5,379 B Washington D. C. 20433, U.S.A. 23rd Floor, The Taipan Place Land ..................................... 298,170 sq. km GDP growth rate (2005) ..................................5.1% Tel: 202-473-1000 F. Ortigas Jr. Ave. (formerly Emerald Ave.) Water ....................................... 1,830 sq. km GDP – composition by sector: Fax:202-477-6391 Ortigas Center, Pasig City, Philippines Boundaries: Agriculture ................................................14% www.worldbank.org Tel: 63-2-637-5855 to 64 North: Balintang Channel Industry .....................................................33% Fax:63-2-637-5870; 917-3050 South: Sulu and Celebes Seas Services ......................................................53% www.worldbank.org.ph East: Philippine Sea/Pacific Ocean Unemployment rate (2005): ..........................10.3% West: South China Sea Gross Domestic Investment/GDP: ..............15.7% December 2005 Coastline: .............................................. 36,289 km Exports of goods and services/GDP: ...........46.4% Maritime claims: Gross domestic savings/GDP: .....................20.1% Total territorial water area incl. Gross national savings/GDP: .......................18.2%