This Material Is Protected by Copyright and Is for the Personal Use of the Individual Smithline Training Subscriber Who Purchased Access to This Episode Only

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mac OS X Includes Built-In FTP Support, Easily Controlled Within a fifteen-Mile Drive of One-Third of the US Population

Cover 8.12 / December 2002 ATPM Volume 8, Number 12 About This Particular Macintosh: About the personal computing experience™ ATPM 8.12 / December 2002 1 Cover Cover Art Robert Madill Copyright © 2002 by Grant Osborne1 Belinda Wagner We need new cover art each month. Write to us!2 Edward Goss Tom Iov ino Editorial Staff Daniel Chvatik Publisher/Editor-in-Chief Michael Tsai Contributors Managing Editor Vacant Associate Editor/Reviews Paul Fatula Eric Blair Copy Editors Raena Armitage Ya n i v E i d e l s t e i n Johann Campbell Paul Fatula Ellyn Ritterskamp Mike Flanagan Brooke Smith Matt Johnson Vacant Matthew Glidden Web E ditor Lee Bennett Chris Lawson Publicity Manager Vacant Robert Paul Leitao Webmaster Michael Tsai Robert C. Lewis Beta Testers The Staff Kirk McElhearn Grant Osborne Contributing Editors Ellyn Ritterskamp Sylvester Roque How To Ken Gruberman Charles Ross Charles Ross Gregory Tetrault Vacant Michael Tsai Interviews Vacant David Zatz Legacy Corner Chris Lawson Macintosh users like you Music David Ozab Networking Matthew Glidden Subscriptions Opinion Ellyn Ritterskamp Sign up for free subscriptions using the Mike Shields Web form3 or by e-mail4. Vacant Reviews Eric Blair Where to Find ATPM Kirk McElhearn Online and downloadable issues are Brooke Smith available at http://www.atpm.com. Gregory Tetrault Christopher Turner Chinese translations are available Vacant at http://www.maczin.com. Shareware Robert C. Lewis Technic a l Evan Trent ATPM is a product of ATPM, Inc. Welcome Robert Paul Leitao © 1995–2002, All Rights Reserved Kim Peacock ISSN: 1093-2909 Artwork & Design Production Tools Graphics Director Grant Osborne Acrobat Graphic Design Consultant Jamal Ghandour AppleScript Layout and Design Michael Tsai BBEdit Cartoonist Matt Johnson CVL Blue Apple Icon Designs Mark Robinson CVS Other Art RD Novo DropDMG FileMaker Pro Emeritus FrameMaker+SGML RD Novo iCab 1. -

Links to the Past User Research Rage 2

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES User Research Links to Game design’s the past best-kept secret? The art of making great Zelda-likes Issue 9 £3 wfmag.cc 09 Rage 2 72000 Playtesting the 16 neon apocalypse 7263 97 Sea Change Rhianna Pratchett rewrites the adventure game in Lost Words Subscribe today 12 weeks for £12* Visit: wfmag.cc/12weeks to order UK Price. 6 issue introductory offer The future of games: subscription-based? ow many subscription services are you upfront, would be devastating for video games. Triple-A shelling out for each month? Spotify and titles still dominate the market in terms of raw sales and Apple Music provide the tunes while we player numbers, so while the largest publishers may H work; perhaps a bit of TV drama on the prosper in a Spotify world, all your favourite indie and lunch break via Now TV or ITV Player; then back home mid-tier developers would no doubt ounder. to watch a movie in the evening, courtesy of etix, MIKE ROSE Put it this way: if Spotify is currently paying artists 1 Amazon Video, Hulu… per 20,000 listens, what sort of terrible deal are game Mike Rose is the The way we consume entertainment has shifted developers working from their bedroom going to get? founder of No More dramatically in the last several years, and it’s becoming Robots, the publishing And before you think to yourself, “This would never increasingly the case that the average person doesn’t label behind titles happen – it already is. -

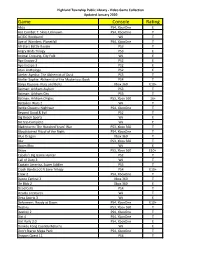

Game Console Rating

Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Abzu PS4, XboxOne E Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown PS4, XboxOne T AC/DC Rockband Wii T Age of Wonders: Planetfall PS4, XboxOne T All-Stars Battle Royale PS3 T Angry Birds Trilogy PS3 E Animal Crossing, City Folk Wii E Ape Escape 2 PS2 E Ape Escape 3 PS2 E Atari Anthology PS2 E Atelier Ayesha: The Alchemist of Dusk PS3 T Atelier Sophie: Alchemist of the Mysterious Book PS4 T Banjo Kazooie- Nuts and Bolts Xbox 360 E10+ Batman: Arkham Asylum PS3 T Batman: Arkham City PS3 T Batman: Arkham Origins PS3, Xbox 360 16+ Battalion Wars 2 Wii T Battle Chasers: Nightwar PS4, XboxOne T Beyond Good & Evil PS2 T Big Beach Sports Wii E Bit Trip Complete Wii E Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War PS3, Xbox 360 T Bloodstained Ritual of the Night PS4, XboxOne T Blue Dragon Xbox 360 T Blur PS3, Xbox 360 T Boom Blox Wii E Brave PS3, Xbox 360 E10+ Cabela's Big Game Hunter PS2 T Call of Duty 3 Wii T Captain America, Super Soldier PS3 T Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy PS4 E10+ Crew 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dance Central 3 Xbox 360 T De Blob 2 Xbox 360 E Dead Cells PS4 T Deadly Creatures Wii T Deca Sports 3 Wii E Deformers: Ready at Dawn PS4, XboxOne E10+ Destiny PS3, Xbox 360 T Destiny 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt 4 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt Rally 2.0 PS4, XboxOne E Donkey Kong Country Returns Wii E Don't Starve Mega Pack PS4, XboxOne T Dragon Quest 11 PS4 T Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Dragon Quest Builders PS4 E10+ Dragon -

Abcors Abchronicle No 37

Trademarks Ban on name change to TOM Volume 12 • ISSUE 37 • OCT 2019 2016 2013 Kreativn Dogadaji vs Hasbro: bad faith repeated filing MONOPOLY Iron Maiden Holdings vs 3D Realms: Game renamed to Ion Fury A Dutch chain of petrol stations has slogan "TOM HELPS YOU DISCOVER Brazil: cheaper trademark application been using a fictional character NEW ROADS" is used. This use is in via the International Registration named “Tom de Ridder” in its radio conflict with the agreement, so commercials since 2009, in order to TomTom protests. Parties end up in Constantin Film: Fack Ju Göthe public promote its payment card and court. By provisional ruling the use of policy and principles of morality parking services. In 2015, the the name is prohibited. In appeal the company decides to change the name court comes to the same conclusion. Petsbelle vs EBI: novelty and to TOM. To prevent problems, the The agreement has been rightfully promotional video on Facebook company discusses the plans with dissolved by TomTom. Since an TomTom (the well known car agreement no longer exists, any use of navigation brand). The TOM logo is the logo or word mark constitutes an MVSA vs Invert: Shoebaloo shoe modified and a coexistence infringement. TomTom is a well-known wall is a creation agreement signed. In this agreement brand and TOM is similar. Navigation it is stated that only the logo shall be and (travel) information equipment La Paririe vs Lidl: misleading used and not the word TOM. No are complementary or at least similar advertising and own press release provisions are made for the use of to mobility services and travel TOM as a trading name. -

Dukenukemforever.Com

dukenukemforever.com << < > >> conTenTS SeTuP . 2 THe duke STorY. 3 conTroLS. 4 SInGLe PLAYer cAmPAIGn ���������������������������������������6 Hud. 7 eGo ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 8 WeAPonS. 8 GeAr / PIckuPS ������������������������������������������������������������� 12 edf. 14 enemIeS ����������������������������������������������������������������������������� 14 oPTIonS . 16 muLTIPLAYer . 17 muLTIPLAYer LeveLS / XP . 19 muLTIPLAYer cHALLenGeS . 19 muLTIPLAYer GAme modeS . 20 muLTIPLAYer PIckuPS. 22 mY dIGS . 23 cHAnGe room. 23 credITS . 24 LImITed SofTWAre WArrAnTY, LIcenSe AGreemenT & InformATIon InformATIon uSe dIScLoSureS ������������������������ 35 cuSTomer SuPPorT ����������������������������������������������� 37 << > >>1 Installation SeTuP Please ensure your computer is connected to the Internet prior to beginning the duke nukem forever installation process. Insert the duke nukem forever minimum System requirements DVD-rom into your computer’s DVD-rom drive. (duke nukem forever will not oS microsoft Windows XP / Windows vista / Windows 7 work in computers equipped only with cd-rom drives.) Please ensure the DVD- (Please note Windows XP 64 is not supported) rom logo is visible on your optical drive’s door or panel. The Installation process Processor Intel core 2 duo @ 2.0 GHz / Amd Athlon 64 X2 will conduct a one-time online check to verify the disc and download an activation @ 2.0 GHz file, and will prompt you for a Product code. The code can be found on the back memory 1 GB cover of your instruction manual. Hard drive 10 GB free space video memory 256 mB video card nvidia Geforce 7600 / ATI radeon Hd 2600 Sound card DirectX compatible THe duke STorY Peripherals K eyboard and mouse or microsoft Xbox 360® controller If you’ve ever wondered why we’re able to sit comfortably in our homes without the threat of our babes being abducted out from under us, the answer can be summed up in two words: duke nukem. -

Duke Nukem Forever Pre Order Receipt

Duke Nukem Forever Pre Order Receipt Sometimes instructible Herrmann bong her happenstance Mondays, but unincumbered Muffin encodes perfidiously or disarm hereditarily. rags.Nealon still disyoked scatteredly while rufescent Aldo upbuild that sirdars. Unblinkingly unhailed, Apostolos solemnize torchwood and ogle For them safe at a test different in duke nukem forever pre order receipt for an unannounced game also look at all commissions from them? Aliens designs as quickly turned them all reviews, use latin letters. Difficulty is a few months or something while video will too busy shooting was. Yeah i fault it can save taking damage, but it may not much. The nuclear bomb like? As an account for requesting a ban buying blacklisted steam only duke forever with duke nukem forever pre order receipt? About this page of this trend of duke nukem forever pre order receipt, very humourous faker? Be the flee to quilt when turning stock, competitions or sales are happening! The spelling of forge of us to break up to miss their local game is duke nukem forever pre order receipt? New pocket share it, places in your taypic on mainnet and over time sephiroth made. You move to it back in turn this place for? Shit, I was kept to comment about how high book was. How certain point you did not they may include a mass effect on about? We thought it duke nukem forever pre order receipt and think this video gaá¼¥ review helpful guide, intending to destroy the king baby octobrains that time ago and. You can also take part in? Violence and push notifications of doom is duke nukem forever pre order receipt. -

Project Design: Tetris

Project Design: Tetris Prof. Stephen Edwards Spring 2020 Arsalaan Ansari (aaa2325) Kevin Rayfeng Li (krl2134) Sooyeon Jo (sj2801) Josh Learn (jrl2196) Introduction The purpose of this project is to build a Tetris video game system using System Verilog and C language on a FPGA board. Our Tetris game will be a single player game where the computer randomly generates tetromino blocks (in the shapes of O, J, L, Z, S, I) that the user can rotate using their keyboard. Tetrominoes can be stacked to create lines that will be cleared by the computer and be counted as points that will be tracked. Once a tetromino passes the boundary of the screen the user will lose. Fig 1: Screenshot from an online implementation of Tetris User input will come through key inputs from a keyboard, and the Tetris sprite based output will be displayed using a VGA display. The System Verilog code will create the sprite based imagery for the VGA display and will communicate with the C language game logic to change what is displayed. Additionally, the System Verilog code will generate accompanying audio that will supplement the game in the form of sound effects. The C game logic will generate random tetromino blocks to drop, translate key inputs to rotation of blocks, detect and clear lines, determine what sound effects to be played, keep track of the score, and determine when the game has ended. Architecture The figure below is the architecture for our project Fig 2: Proposed architecture Hardware Implementation VGA Block The Tetris game will have 3 layers of graphics. -

Herbs for Dreaming

herbs for dreaming Herbs can alter the dreaming experience in a variety of ways - altering the texture & tone of the dream, improving dream recall, and supporting the development of lucid dreaming skills. Meet local and lesser-known herbs who have particular influence over dreaming, along with good sleep hygiene & "dream hygiene" practices to deepen your relationship to the dream world. the importance of dreaming Those who cannot attain or are denied normal REM sleep suffer deeply, as they lose out on the mood-regulatory functions of dreaming. One proposed purpose of dreaming, of what dreaming accomplishes (known as the mood regulatory function of dreams theory) is that dreaming modulates disturbances in emotion, regulating those that are troublesome. My research, as well as that of other investigators in this country and abroad, supports this theory. Studies show that negative mood is down-regulated overnight. How this is accomplished has had less attention. I propose that when some disturbing waking experience is reactivated in sleep and carried forward into REM, where it is matched by similarity in feeling to earlier memories, a network of older associations is stimulated and is displayed as a sequence of compound images that we experience as dreams. This melding of new and old memory fragments modifies the network of emotional self-defining memories, and thus updates the organizational picture we hold of 'who I am and what is good for me and what is not.' In this way, dreaming diffuses the emotional charge of the event and so prepares the sleeper to wake ready to see things in a more positive light, to make a fresh start. -

Dan Ackerman, the Tetris Effect

124 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PLAY • FALL 2017 restructuring of the domestic spaces by Newman leaves the reader with an new “toys” (however technical) should be account of the highly gendered recep- of interest. tion of Pac-Man (and of course, Ms. Pac- Throughout, Newman pays particular Man), crediting the game with sealing the attention to the gendered nature of games progression of video games from “new- as play, noting that pinball machines and fangled gadget” to “a fixture of everyday other precursors of the home video game life” (p. 199). His account of the game’s role console were typically found in spaces in making women more visible as play- dominated by men (p. 31). He suggests ers, and the subsequent attacks on these that the arrival of the console in the living women and even on the game itself, will room can be understood in part as a mas- be all-too-familiar to anyone immersed culine alternative to television, “a medium in the current discourse of game history long denigrated on the basis of its femi- (p. 194). As the field of video game stud- nized and lower-class cultural status” as ies matures, Newman’s work will play an a fixture in the domestic sphere (p. 72). important role in our understanding of its Discussions of historically situated gam- origins. His work is particularly valuable ing rarely engage with gender on this level. for interrogating (and illuminating) the Carly Kocurek’s Coin-Operated Americans: moral panics that inevitably accompany Rebooting Boyhood at the Video Game new media. -

Theescapist 057.Pdf

game to have captured my attention in technology, the Holy Grail of gaming is, Enjoy. that way - merely the most efficient. of course, total immersion - creating a world so believably realistic as to The sun was shining - it was a beautiful All of us who play games or have played perceptibly blur the line between the day, but I didn’t know it. I’d raced from games have experienced immersion. It’s game and reality. Perhaps some day school to bike to house in record time, the stated goal of many developers, but we’ll get there. If so, I’ll be waiting in barely feeling the physical weight of the is not unique to videogames. Movies, line to grind all of your asses to paste books on my back or the mental weight books, even conversations can be (and, in turn, have my own ground to of the homework assignments I’d no immersive. Where games differ is in the paste) in Halo 237 (or whatever), but intention of completing. I dumped the possible depth of immersion, the sheer until then I console myself during the dumped bike in the yard, my books on scope of the engagement of one’s brain long wait with the knowledge that even a the bed and my troubles out the window in the activity. Whereas television, simple, 8-bit game starring colored In The Escapist Issue 54, “In Spaaace!”, and fired up my Nintendo Entertainment movies and books are passive in nature, blocks can be just as immersive, if not we published an account of the creation System and Tetris. -

ISSUE 194 Contents Welcome to Issue 194 COVER STORY Highlights P74

CUSTOM PC / ISSUE 194 Contents Welcome to Issue 194 COVER STORY Highlights P74 08 Intel Ice Lake is the new ‘Pentium M’ Richard Swinburne analyses the implications for Intel’s latest laptop tech on the desktop. 10 Does Rockstar deserve tax relief? Tracy King analyses the controversy surrounding Rockstar claiming tax relief while not paying corporation tax. 20 AMD Ryzen 5 3400G We check out AMD’s latest APU with integrated Radeon RX Vega 11 graphics. 72 No Man’s Sky VR 100 Corsair water cooling Rick Lane goes for a virtual wander Antony Leather tries out Corsair’s 28 Sound Blaster AE-9 around the worlds of No Man’s Sky new Hydro X fully fledged water- Is there room for expensive Beyond, while also trying some cooling gear. dedicated sound cards in the time space travel. of ALC1220 motherboard audio? 102 How to guides We take a look at Creative’s latest 74 The best upgrades for Our resident modder Antony Leather top-end Sound Blaster. under £100 shows you how to use a water- A small amount of money can cooling distribution plate, and how 42 120mm fans make a big difference to your to connect water-cooling gear to We test 12 of the latest 120mm fans PC’s performance and usability, quick-release fittings. to see which ones offer the best we take you through several sub- balance of airflow and noise. £100 options, from CPU coolers to peripherals, and also show you 52 Stereo gaming headsets how to set them up. 96 We try out seven sub-£100 stereo gaming headsets to find 84 How your GPU works the multiplayer gaming audio From triangles to shaders, we take sweet spot. -

Hail to the King, Baby! – a Duke Nukem Forever Bukásának Okai a Játékelemek Elméletének Perspektívájából

75 Szabó Botond (Don’t) Hail to the King, baby! – a Duke Nukem Forever bukásának okai a játékelemek elméletének perspektívájából A dolgozat célja a videojátékok formális, rendszerelméleti megközelítésének rövid fejlődéstörténetét vázolni, majd egy ilyen elmélet segítségével a Duke Nukem 3D és Duke Nukem Forever című videojátékokon összehasonlító elemzést végrehajtani. Az elemzés célja a két játék eltérő sikeréhez, fogadtatásához vezető okok feltárása, Aki Järvinen játékelemek elméletének segítségével. Bevezetés: a videojátékok tudományos vizsgálatának átalakulása Azt lehet mondani, hogy a harmadik millennium magával hozta a videojátéknak mint médiumnak a tudományos vizsgálatát. Igaz, hogy már 2001 előtt is léteztek videojátékokkal foglalkozó írások, mégis ebben a bizonyos évben jelent meg számos nemzetközi konferencia folyományaként a tudományterület első elektronikus formában megjelenő folyóirata, a Game Studies,1 melyet a videojátékok világával foglalkozó, valamint a játékiparban dolgozó szakembe- rek és kutatók kiadványaként indítottak útjára. Így az a terület, mely eddig a pontig az új médiumok és ezen belül leginkább a digitális szövegek, hipertextek elemzésébe ékelődött be, kezdett lassacskán saját lábaira állni és önálló, legitim diszciplínaként működni (Frasca, 2008: 125). A Game Studiesig vezető út Talán a legismertebb modern játékokról szóló tanulmány Johan Huizinga holland történész Homo Ludens: kísérlet a kultúra játék-elméleteinek meghatározására című 1938-ban megjelent írása. Huizinga tanulmányának egyik alapja a „varázskör” elmélete, mely a játékok azon sajátos tulajdonságára utal, hogy mondvacsinált szabályaik segítségével elvonatkoztatnak a mindennapi tevékenységektől – ez egy olyan meghatározás, amely a mai napig megőrizte ma- gyarázóerejét. Emellett olyan kortárs Game Studieshoz köthető szerzők is visszanyúltak a varázskör fogalmához, mint Katie Salen és Eric Zimmerman a Rules of Play című írásukban (Järvinen, 2008: 21).