BOOK the Tetris Effect: the Game That Hypnotized the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Links to the Past User Research Rage 2

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES User Research Links to Game design’s the past best-kept secret? The art of making great Zelda-likes Issue 9 £3 wfmag.cc 09 Rage 2 72000 Playtesting the 16 neon apocalypse 7263 97 Sea Change Rhianna Pratchett rewrites the adventure game in Lost Words Subscribe today 12 weeks for £12* Visit: wfmag.cc/12weeks to order UK Price. 6 issue introductory offer The future of games: subscription-based? ow many subscription services are you upfront, would be devastating for video games. Triple-A shelling out for each month? Spotify and titles still dominate the market in terms of raw sales and Apple Music provide the tunes while we player numbers, so while the largest publishers may H work; perhaps a bit of TV drama on the prosper in a Spotify world, all your favourite indie and lunch break via Now TV or ITV Player; then back home mid-tier developers would no doubt ounder. to watch a movie in the evening, courtesy of etix, MIKE ROSE Put it this way: if Spotify is currently paying artists 1 Amazon Video, Hulu… per 20,000 listens, what sort of terrible deal are game Mike Rose is the The way we consume entertainment has shifted developers working from their bedroom going to get? founder of No More dramatically in the last several years, and it’s becoming Robots, the publishing And before you think to yourself, “This would never increasingly the case that the average person doesn’t label behind titles happen – it already is. -

Studio Showcase

Contacts: Holly Rockwood Tricia Gugler EA Corporate Communications EA Investor Relations 650-628-7323 650-628-7327 [email protected] [email protected] EA SPOTLIGHTS SLATE OF NEW TITLES AND INITIATIVES AT ANNUAL SUMMER SHOWCASE EVENT REDWOOD CITY, Calif., August 14, 2008 -- Following an award-winning presence at E3 in July, Electronic Arts Inc. (NASDAQ: ERTS) today unveiled new games that will entertain the core and reach for more, scheduled to launch this holiday and in 2009. The new games presented on stage at a press conference during EA’s annual Studio Showcase include The Godfather® II, Need for Speed™ Undercover, SCRABBLE on the iPhone™ featuring WiFi play capability, and a brand new property, Henry Hatsworth in the Puzzling Adventure. EA Partners also announced publishing agreements with two of the world’s most creative independent studios, Epic Games and Grasshopper Manufacture. “Today’s event is a key inflection point that shows the industry the breadth and depth of EA’s portfolio,” said Jeff Karp, Senior Vice President and General Manager of North American Publishing for Electronic Arts. “We continue to raise the bar with each opportunity to show new titles throughout the summer and fall line up of global industry events. It’s been exciting to see consumer and critical reaction to our expansive slate, and we look forward to receiving feedback with the debut of today’s new titles.” The new titles and relationships unveiled on stage at today’s Studio Showcase press conference include: • Need for Speed Undercover – Need for Speed Undercover takes the franchise back to its roots and re-introduces break-neck cop chases, the world’s hottest cars and spectacular highway battles. -

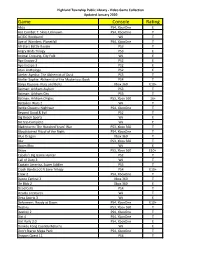

Game Console Rating

Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Abzu PS4, XboxOne E Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown PS4, XboxOne T AC/DC Rockband Wii T Age of Wonders: Planetfall PS4, XboxOne T All-Stars Battle Royale PS3 T Angry Birds Trilogy PS3 E Animal Crossing, City Folk Wii E Ape Escape 2 PS2 E Ape Escape 3 PS2 E Atari Anthology PS2 E Atelier Ayesha: The Alchemist of Dusk PS3 T Atelier Sophie: Alchemist of the Mysterious Book PS4 T Banjo Kazooie- Nuts and Bolts Xbox 360 E10+ Batman: Arkham Asylum PS3 T Batman: Arkham City PS3 T Batman: Arkham Origins PS3, Xbox 360 16+ Battalion Wars 2 Wii T Battle Chasers: Nightwar PS4, XboxOne T Beyond Good & Evil PS2 T Big Beach Sports Wii E Bit Trip Complete Wii E Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War PS3, Xbox 360 T Bloodstained Ritual of the Night PS4, XboxOne T Blue Dragon Xbox 360 T Blur PS3, Xbox 360 T Boom Blox Wii E Brave PS3, Xbox 360 E10+ Cabela's Big Game Hunter PS2 T Call of Duty 3 Wii T Captain America, Super Soldier PS3 T Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy PS4 E10+ Crew 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dance Central 3 Xbox 360 T De Blob 2 Xbox 360 E Dead Cells PS4 T Deadly Creatures Wii T Deca Sports 3 Wii E Deformers: Ready at Dawn PS4, XboxOne E10+ Destiny PS3, Xbox 360 T Destiny 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt 4 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt Rally 2.0 PS4, XboxOne E Donkey Kong Country Returns Wii E Don't Starve Mega Pack PS4, XboxOne T Dragon Quest 11 PS4 T Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Dragon Quest Builders PS4 E10+ Dragon -

Pynchon's Sound of Music

Pynchon’s Sound of Music Christian Hänggi Pynchon’s Sound of Music DIAPHANES PUBLISHED WITH SUPPORT BY THE SWISS NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION 1ST EDITION ISBN 978-3-0358-0233-7 10.4472/9783035802337 DIESES WERK IST LIZENZIERT UNTER EINER CREATIVE COMMONS NAMENSNENNUNG 3.0 SCHWEIZ LIZENZ. LAYOUT AND PREPRESS: 2EDIT, ZURICH WWW.DIAPHANES.NET Contents Preface 7 Introduction 9 1 The Job of Sorting It All Out 17 A Brief Biography in Music 17 An Inventory of Pynchon’s Musical Techniques and Strategies 26 Pynchon on Record, Vol. 4 51 2 Lessons in Organology 53 The Harmonica 56 The Kazoo 79 The Saxophone 93 3 The Sounds of Societies to Come 121 The Age of Representation 127 The Age of Repetition 149 The Age of Composition 165 4 Analyzing the Pynchon Playlist 183 Conclusion 227 Appendix 231 Index of Musical Instruments 233 The Pynchon Playlist 239 Bibliography 289 Index of Musicians 309 Acknowledgments 315 Preface When I first read Gravity’s Rainbow, back in the days before I started to study literature more systematically, I noticed the nov- el’s many references to saxophones. Having played the instru- ment for, then, almost two decades, I thought that a novelist would not, could not, feature specialty instruments such as the C-melody sax if he did not play the horn himself. Once the saxophone had caught my attention, I noticed all sorts of uncommon references that seemed to confirm my hunch that Thomas Pynchon himself played the instrument: McClintic Sphere’s 4½ reed, the contra- bass sax of Against the Day, Gravity’s Rainbow’s Charlie Parker passage. -

Electronic Arts V. Zynga: Real Dispute Over Virtual Worlds Jennifer Kelly and Leslie Kramer

Electronic Arts v. Zynga: Real Dispute Over Virtual Worlds jennifer kelly and leslie kramer Electronic Arts Inc.’s (“EA”) recent lawsuit against relates to these generally accepted categories of Zynga Inc. (“Zynga”) filed in the Northern District of protectable content, thereby giving rise to a claim for California on August 3, 2012 is the latest in a string of infringement, is not as easy as one might think. disputes where a video game owner has asserted that an alleged copycat game has crossed the line between There are a couple of reasons for this. First, copying of lawful copying and copyright infringement. See N.D. games has become so commonplace in today’s game Cal. Case No. 3:12-cv-04099. There, EA has accused industry (insiders refer to the practice as “fast follow”) Zynga of infringing its copyright in The Sims Social, that often it is hard to determine who originated which is EA’s Facebook version of its highly successful the content at issue. A common—and surprisingly PC and console-based game, The Sims. Both The Sims effective—defense is that the potential plaintiff itself and The Sims Social are virtual world games in which copied the expression from some other game (or the player simulates the daily activities of one or perhaps, a book or a film), and thus, has no basis more virtual characters in a household located in the to assert a claim over that content. In this scenario, fictional town of SimCity. In the lawsuit, EA contends whether the alleged similarities between the two that Zynga’s The Ville, released for the Facebook games pertain to protectable expression becomes, platform in June 2012, copies numerous protectable frankly, irrelevant. -

The Game of Tetris in Machine Learning

The Game of Tetris in Machine Learning Simon´ Algorta 1 Ozg¨ ur¨ S¸ims¸ek 2 Abstract proaches to other games and to real-world problems. In the Appendix we provide a table of the algorithms reviewed The game of Tetris is an important benchmark and a description of the features used. for research in artificial intelligence and ma- chine learning. This paper provides a histori- cal account of the algorithmic developments in 2. The Game of Tetris Tetris and discusses open challenges. Hand- Tetris is one of the most well liked video games of all time. crafted controllers, genetic algorithms, and rein- It was created by Alexey Pajitnov in the USSR in 1984. forcement learning have all contributed to good It quickly turned into a popular culture icon that ignited solutions. However, existing solutions fall far copyright battles amid the tensions of the final years of the short of what can be achieved by expert players Cold War (Temple, 2004). playing without time pressure. Further study of the game has the potential to contribute to impor- The game is played on a two-dimensional grid, initially tant areas of research, including feature discov- empty. The grid gradually fills up as pieces of different ery, autonomous learning of action hierarchies, shapes, called Tetriminos, fall from the top, one at a time. and sample-efficient reinforcement learning. The player can control how each Tetrimino lands by rotat- ing it and moving it horizontally, to the left or to the right, any number of times, as it falls one row at a time until one 1. -

Project Design: Tetris

Project Design: Tetris Prof. Stephen Edwards Spring 2020 Arsalaan Ansari (aaa2325) Kevin Rayfeng Li (krl2134) Sooyeon Jo (sj2801) Josh Learn (jrl2196) Introduction The purpose of this project is to build a Tetris video game system using System Verilog and C language on a FPGA board. Our Tetris game will be a single player game where the computer randomly generates tetromino blocks (in the shapes of O, J, L, Z, S, I) that the user can rotate using their keyboard. Tetrominoes can be stacked to create lines that will be cleared by the computer and be counted as points that will be tracked. Once a tetromino passes the boundary of the screen the user will lose. Fig 1: Screenshot from an online implementation of Tetris User input will come through key inputs from a keyboard, and the Tetris sprite based output will be displayed using a VGA display. The System Verilog code will create the sprite based imagery for the VGA display and will communicate with the C language game logic to change what is displayed. Additionally, the System Verilog code will generate accompanying audio that will supplement the game in the form of sound effects. The C game logic will generate random tetromino blocks to drop, translate key inputs to rotation of blocks, detect and clear lines, determine what sound effects to be played, keep track of the score, and determine when the game has ended. Architecture The figure below is the architecture for our project Fig 2: Proposed architecture Hardware Implementation VGA Block The Tetris game will have 3 layers of graphics. -

Concert Program

Gamer Symphony Orchestra Spring 2014 Concert Saturday, May 3, 2014, 2 p.m. Dekelboum Concert Hall Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center Jacob Coppage-Gross, Conductor Kevin Mok, Conductor Kyle G. Jamolin, Choral Director Bryan Doyle, Assistant Conductor About the GSO In the fall of 2005, student violist Michelle Eng sought to create an orchestral group that played video game music. With a half-dozen others from the University of Maryland Repertoire Orchestra, she founded GSO to achieve that dream. By the time of the ensemble’s first public performance in spring 2006, its size had quadrupled. Today GSO provides a musical and social outlet to 120 members. It is the world’s first collegiate ensemble to draw its repertoire exclusively from the soundtracks of video games. The ensemble is entirely student run, which includes conducting and musical arranging. In February of 2012 the GSO collaborated with Video Games Live!, for the performances at the Strathmore in Bethesda, Md. The National Philharmonic per- formed the GSO’s arrangement of “Korobeiniki” from Tetris to two sold-out houses. In May of 2012 the GSO was invited to perform as part of the Smithsonian’s The Art of Video Games exhibit. Aside from its concerts, GSO also holds the “Deathmatch for Charity” (renamed the “Gamer Olympics” this year) video game tournament every spring. All proceeds benefit Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, D.C. Find GSO online at UMD.gamersymphony.org Beyond the GSO The GSO has also fostered the creation of a multitude of other collegiate GSOs at California State University—Northridge, Ithaca College, Montclair State University, the University of California—Los Angeles, the University of Delaware, and West Char- ter University. -

Herbs for Dreaming

herbs for dreaming Herbs can alter the dreaming experience in a variety of ways - altering the texture & tone of the dream, improving dream recall, and supporting the development of lucid dreaming skills. Meet local and lesser-known herbs who have particular influence over dreaming, along with good sleep hygiene & "dream hygiene" practices to deepen your relationship to the dream world. the importance of dreaming Those who cannot attain or are denied normal REM sleep suffer deeply, as they lose out on the mood-regulatory functions of dreaming. One proposed purpose of dreaming, of what dreaming accomplishes (known as the mood regulatory function of dreams theory) is that dreaming modulates disturbances in emotion, regulating those that are troublesome. My research, as well as that of other investigators in this country and abroad, supports this theory. Studies show that negative mood is down-regulated overnight. How this is accomplished has had less attention. I propose that when some disturbing waking experience is reactivated in sleep and carried forward into REM, where it is matched by similarity in feeling to earlier memories, a network of older associations is stimulated and is displayed as a sequence of compound images that we experience as dreams. This melding of new and old memory fragments modifies the network of emotional self-defining memories, and thus updates the organizational picture we hold of 'who I am and what is good for me and what is not.' In this way, dreaming diffuses the emotional charge of the event and so prepares the sleeper to wake ready to see things in a more positive light, to make a fresh start. -

Dan Ackerman, the Tetris Effect

124 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PLAY • FALL 2017 restructuring of the domestic spaces by Newman leaves the reader with an new “toys” (however technical) should be account of the highly gendered recep- of interest. tion of Pac-Man (and of course, Ms. Pac- Throughout, Newman pays particular Man), crediting the game with sealing the attention to the gendered nature of games progression of video games from “new- as play, noting that pinball machines and fangled gadget” to “a fixture of everyday other precursors of the home video game life” (p. 199). His account of the game’s role console were typically found in spaces in making women more visible as play- dominated by men (p. 31). He suggests ers, and the subsequent attacks on these that the arrival of the console in the living women and even on the game itself, will room can be understood in part as a mas- be all-too-familiar to anyone immersed culine alternative to television, “a medium in the current discourse of game history long denigrated on the basis of its femi- (p. 194). As the field of video game stud- nized and lower-class cultural status” as ies matures, Newman’s work will play an a fixture in the domestic sphere (p. 72). important role in our understanding of its Discussions of historically situated gam- origins. His work is particularly valuable ing rarely engage with gender on this level. for interrogating (and illuminating) the Carly Kocurek’s Coin-Operated Americans: moral panics that inevitably accompany Rebooting Boyhood at the Video Game new media. -

Theescapist 057.Pdf

game to have captured my attention in technology, the Holy Grail of gaming is, Enjoy. that way - merely the most efficient. of course, total immersion - creating a world so believably realistic as to The sun was shining - it was a beautiful All of us who play games or have played perceptibly blur the line between the day, but I didn’t know it. I’d raced from games have experienced immersion. It’s game and reality. Perhaps some day school to bike to house in record time, the stated goal of many developers, but we’ll get there. If so, I’ll be waiting in barely feeling the physical weight of the is not unique to videogames. Movies, line to grind all of your asses to paste books on my back or the mental weight books, even conversations can be (and, in turn, have my own ground to of the homework assignments I’d no immersive. Where games differ is in the paste) in Halo 237 (or whatever), but intention of completing. I dumped the possible depth of immersion, the sheer until then I console myself during the dumped bike in the yard, my books on scope of the engagement of one’s brain long wait with the knowledge that even a the bed and my troubles out the window in the activity. Whereas television, simple, 8-bit game starring colored In The Escapist Issue 54, “In Spaaace!”, and fired up my Nintendo Entertainment movies and books are passive in nature, blocks can be just as immersive, if not we published an account of the creation System and Tetris. -

Human-Computer Interaction in 3D Object Manipulation in Virtual Environments: a Cognitive Ergonomics Contribution Sarwan Abbasi

Human-computer interaction in 3D object manipulation in virtual environments: A cognitive ergonomics contribution Sarwan Abbasi To cite this version: Sarwan Abbasi. Human-computer interaction in 3D object manipulation in virtual environments: A cognitive ergonomics contribution. Computer Science [cs]. Université Paris Sud - Paris XI, 2010. English. tel-00603331 HAL Id: tel-00603331 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00603331 Submitted on 24 Jun 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Human‐computer interaction in 3D object manipulation in virtual environments: A cognitive ergonomics contribution Doctoral Thesis submitted to the Université de Paris‐Sud 11, Orsay Ecole Doctorale d'Informatique Laboratoire d'Informatique pour la Mécanique et les Sciences de l'Ingénieur (LIMSI‐CNRS) 26 November 2010 By Sarwan Abbasi Jury Michel Denis (Directeur de thèse) Jean‐Marie Burkhardt (Co‐directeur) Françoise Détienne (Rapporteur) Stéphane Donikian (Rapporteur) Philippe Tarroux (Examinateur) Indira Thouvenin (Examinatrice) Object Manipulation in Virtual Environments Thesis Report by Sarwan ABBASI Acknowledgements One of my former professors, M. Ali YUSUF had once told me that if I learnt a new language in a culture different than mine, it would enable me to look at the world in an entirely new way and in fact would open up for me a whole new world for me.