Women's Artistic Gymnastics During the Cold War and Its Aftermath

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indian Gymnast

indian gymnast Volume.24 No. 1 January.2016 DIPA KARMAKAR DURING WORLD GYMNASTICS CHAMPIONSHIPS, FIRST INDIAN WOMAN GYMNAST TO QUALIFY FOR THE APPARATUS FINAL COMPETITION IN VAULT IN THE 46th WORLD GYMNASTICS CHAMPIONSHIPS A BI-ANNUAL GYMNASTICS PUBLICATION INDIAN GYMNASTICS CONTINGENT IN GLASGOW (SCOTLAND) FOR PARTICIPATION IN THE 46TH WORLD GYMNASTICS CHAMPIONSHIPS HELD FROM 23rd OCT. to 1st NOV. 2015 Dr. G.S.Bawa with Jordan Jovtchev, the Olympic Silver Medalist and World Champion(4 Gold, 5 Silver and 4 Bronze medals) who participated in 6 Consecutive Olympic Games and presently he is President of Bulgarian Gymnastics Federation Indian Gymnast – A Bi-annual Gymnastics Publication Volume 24 Number 1 January, 2016 - 1 CONTENTS Page Editorial 2 New Elements in MAG Recognized by the FIG 3 by: Steve BUTCHER, President of the Men’s Technical Committee, FIG Rehabilitation for Ankle Sprain 10 by: Ryan Harber, LAT, ATC, CSCS Technique and Methodic of Stalder on Uneven Bars. 15 [by: Dr. Kalpana Debnath. Chief Gymnastics Coach, SAI NS NIS Patiala [ 17 History of Development of Floor Exercises by: Prof. Istvan Karacsony, Hungary th 21 Some Salient Features of 46 Artistic World Gymnastics Championships: by: Dr. Gurdial Singh Bawa, Chief National Coach 54th All India Inter University Gymnastics Championships (MAG, WAG, RG ) 32 organised by Punjabi University Patiala,from 7th to 11th January, 2015 by Dr. Raj Kumar Sharma, Director Sports, Punjabi University,Patiala Results of 46th Artistic World Gymnastics Championships, held at Glasgow, 37 Scotland , from 23rd Oct. to 1st Nov., 2015 by Dr. Kalpana Debnath. Chief Gymnastics Coach, SAI NS NIS Patiala 34th Rhythmic Gymnastics World Championships in Stuttgart (GER) , from 7th 39 to 13th September, 2015. -

2021 Guide to Gymnastics Team

At Spokane Gymnastics, the coaches focus on encouraging the development of strength, skill and character through gymnastics training in a positive environment. We strive to offer a program where every student has the greatest opportunity to succeed, no matter what their level or goal. We strive to balance teaching proper gymnastics skills, terminology and progressions in a fun environment where students are taught by breaking down the elements of the particular skills, hands- on “spotting” and training, low student-to-coach ratios and positive reinforcement. We believe that gymnastics is not only one of the most rewarding sports with unlimited benefits to other activities, but also FUN! Gymnastics not only increases strength, flexibility and balance, it is also encourages hard work, discipline and determination. Women's Artistic Gymnastics There are four events in Women's Artistic Gymnastics – Vault, Uneven Bars, Balance Beam and Floor Exercise. Although most sports have seasons, gymnastics is a year-round commitment for athletes at the upper levels. Vault A successful vault begins with a strong, accelerated run. The best vaulters explode off the springboard with tremendous quickness during the pre-flight phase of the vault. When the gymnast pushes off of the vault table (also informally referred to as the horse) judges look for proper body position and instantaneous propulsion and explosive force. They watch the height and distance traveled as well as the number of flips and twists. Gymnasts strive to stick their landing by taking no extra steps. Uneven Bars Many consider the uneven bars the most spectacular of women's events, since to be successful the gymnasts must display strength as well as concentration, courage, coordination and split-second timing. -

1989 World Artistic Gymnastics Championships Stuttgart, Germany October 14-22, 1989

1989 World Artistic Gymnastics Championships Stuttgart, Germany October 14-22, 1989 MAG , Team Final Qualif Note Final Note Qualif 1 URS 587.250 2 GDR 580.850 3 CHN 579.300 MAG , All Around Note Final Qualif Note Final Qualif 1 KOROBCHINSKI Igor URS 59.250 2 MOGILNY Valentin URS 59.150 3 LI Jing CHN 58.800 10 CHECHI Yuri ITA 58.300 MAG , Floor Exercise Final Qualif Note Final Note Qualif KOROBCHINSKI 1 URS 9.937 Igor 2 ARTEMOV Vladimir URS 9.875 3 LI Chunyang CHN 9.850 5 CHECHI Yuri ITA 9.775 MAG , Pommel Horse Final Qualif Note Final Note Qualif 1 MOGILNY Valentin URS 10.000 2 WECKER Andreas GDR 9.962 3 LI Jing CHN 9.937 MAG , Rings Final Qualif Note Final Note Qualif 1 AGUILAR Andreas FRG 9.875 2 WECKER Andreas GDR 9.862 3 CHECHI Yuri ITA 9.812 3 MARINICH Vitali URS 9.812 MAG , Vault Final Qualif Note Final Note Qualif 1 BEHREND Joerg GER 9.881 2 KROLL Sylvio GER 9.874 3 ARTEMOV Vladimir URS 9.868 MAG , Parallel Bars Final Qualif Note Final Note Qualif 1 LI Jing CHN 9.900 1 ARTEMOV Vladimir URS 9.900 3 WECKER Andreas GDR 9.887 MAG , Horizontal Bar Final Qualif Note Final Note Qualif 1 LI Chunyang CHN 9.950 2 ARTEMOV Vladimir URS 9.900 3 IKETANI Yukio JPN 9.875 WAG , Team Final Qualif Note Final Note Qualif 1 URS 396.793 2 ROM 394.931 3 CHN 392.116 WAG , All Around Note Note Final Qualif Final Qualif BOGUINSKAYA 1 RUS 39.900 Svetlana 2 LASHENOVA Natalia RUS 39.862 3 STRAGEVA Olga RUS 39.774 WAG , Vault Note Note Final Qualif Final Qualif 1 DUDNIK Olesia URS 9.987 2 BONTAS Cristina ROM 9.950 JOHNSON 2 USA 9.950 Brandy WAG , Uneven Bar Note Final Qualif Note Final Qualif 1 FAN Di CHN 10.000 SILIVAS 1 ROM 10.000 Daniela STRAGEVA 3 URS 9.975 Olga WAG , Balance Beam Final Qualif Note Final Note Qualif 1 SILIVAS Daniela ROM 9.950 2 DUDNIK Olesia URS 9.937 3 POTORAC Gabriela ROM 9.887 WAG , Floor Exercise Final Qualif Note Final Note Qualif 1 SILIVAS Daniela ROM 10.000 1 BOGUINSKAYA Svetlana URS 10.000 3 BONTAS Cristina ROM 9.962 . -

Women in Sport

WOMEN IN SPORT VOLUME VIII OF THE ENCYCLOPAEDIA OF SPORTS MEDICINE AN IOC MEDICAL COMMITTEE PUBLICATION IN COLLABORATION WITH THE INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION OF SPORTS MEDICINE EDITED BY BARBARA L. DRINKWATER WOMEN IN SPORT IOC MEDICAL COMMISSION SUB-COMMISSION ON PUBLICATIONS IN THE SPORT SCIENCES Howard G. Knuttgen PhD (Co-ordinator) Boston, Massachusetts, USA Francesco Conconi MD Ferrara, Italy Harm Kuipers MD, PhD Maastricht, The Netherlands Per A.F.H. Renström MD, PhD Stockholm, Sweden Richard H. Strauss MD Los Angeles, California, USA WOMEN IN SPORT VOLUME VIII OF THE ENCYCLOPAEDIA OF SPORTS MEDICINE AN IOC MEDICAL COMMITTEE PUBLICATION IN COLLABORATION WITH THE INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION OF SPORTS MEDICINE EDITED BY BARBARA L. DRINKWATER ©2000 by distributors Blackwell Science Ltd Marston Book Services Ltd Editorial Offices: PO Box 269 Osney Mead, Oxford OX2 0EL Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4YN 25 John Street, London WC1N 2BL (Orders: Tel: 01235 465500 23 Ainslie Place, Edinburgh EH3 6AJ Fax: 01235 465555) 350 Main Street, Malden MA 02148 5018, USA USA 54 University Street, Carlton Blackwell Science, Inc. Victoria 3053, Australia Commerce Place 10, rue Casimir Delavigne 350 Main Street 75006 Paris, France Malden, MA 02148 5018 (Orders: Tel: 800 759 6102 Other Editorial Offices: 781 388 8250 Blackwell Wissenschafts-Verlag GmbH Fax: 781 388 8255) Kurfürstendamm 57 Canada 10707 Berlin, Germany Login Brothers Book Company 324 Saulteaux Crescent Blackwell Science KK Winnipeg, Manitoba R3J 3T2 MG Kodenmacho Building (Orders: Tel: 204 837-2987) 7–10 Kodenmacho Nihombashi Chuo-ku, Tokyo 104, Japan Australia Blackwell Science Pty Ltd The right of the Authors to be 54 University Street identified as the Authors of this Work Carlton, Victoria 3053 has been asserted in accordance (Orders: Tel: 3 9347 0300 with the Copyright, Designs and Fax: 3 9347 5001) Patents Act 1988. -

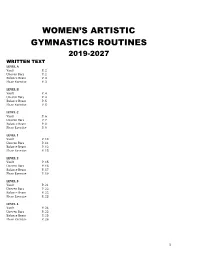

Women's Artistic Gymnastics Routines

WOMEN’S ARTISTIC GYMNASTICS ROUTINES 2019-2027 WRITTEN TEXT LEVEL A Vault P. 2 Uneven Bars P. 2 Balance Beam P. 3 Floor Exercise P. 3 LEVEL B Vault P. 4 Uneven Bars P. 4 Balance Beam P. 5 Floor Exercise P. 5 LEVEL C Vault P. 6 Uneven Bars P. 7 Balance Beam P. 8 Floor Exercise P. 9 LEVEL 1 Vault P. 10 Uneven Bars P. 11 Balance Beam P. 12 Floor Exercise P. 13 LEVEL 2 Vault P. 15 Uneven Bars P. 16 Balance Beam P. 17 Floor Exercise P. 19 LEVEL 3 Vault P. 21 Uneven Bars P. 22 Balance Beam P. 22 Floor Exercise P. 23 LEVEL 4 Vault P. 24 Uneven Bars P. 25 Balance Beam P. 25 Floor Exercise P. 26 1 LEVEL A VAULT (Level A) The video is the official version. This written text is merely an additional teaching tool. * Spotter required May be performed in a wheelchair or with a walker (or other assistance) Value Element 2.0 Salute to judge 2.0 Move to a designated point 2.0 “Stick” landing 2.0 Salute to judge Difficulty 8.0 Execution 2.0 Max. score 10.0 UNEVEN BARS (Level A) The video is the official version of the routine. This written text is merely an additional teaching tool. * Spotter required Performed seated, either with a hand held single bar or the low bar of the uneven bars Value Element 1.0 Salute at beginning of the routine 2.0 Grasp the bar in an overgrip (either simultaneously or one hand at a time) 1.0 Change 1 hand to an undergrip. -

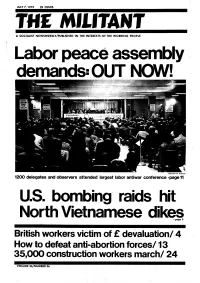

Workers March/ 24

... JULY 7, 1972 25 CENTS A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE .Labor peace as demands= OUT· "• ... -.::. " Militant/Fred Holstead 1200 delegates and observers attended largest labor ~antiwar confer:ence -page 11 ." .U.S .. bombing· raids · hit. .North -Vietnamese dikes -page 3 - British workers victim of £ devaluation/ 4 How to defeat anti-abortion forces/13 ··. 35,000 constru~tion ·workers march/ 24. · ·THIS .WEEK'S .. MEXICAN PRESIDENT' GREETED BY PICKETS: Pres months in a military prison. On June 11 he went on ident Luis Echeverria of Mexico was met by protest dem trial before a military tribunal on charges of evading MILITANT onstrations demanding freedom for political prisoners in the draft. Neuman, a member of the Israeli Socialist Or~ 3 ·U.S. bombs steel mill, Mexico on June 18 and 19 in San Antonio and Los An- ganization, has been singled out from among the thou geles. ' sands of young Israelis who avoid military service for dikes Echeverria served as secretary of state during the Diaz religious or personal reasons because of his unwilling 4 British pound devalued Ordaz regime, when hundreds of students. were gunned ness to serve in an army of occupation and "to par 5 7,000 in. N.Y. gay pride down by police and soldiers in Mexico City in 1968. ticipate in the oppression of another nation." action He was president during the June 10, 1971, massacre A petition on Neuman's behalf will appear as an ad 8U. N. environment con of students by right-wing gangs. Many Mexican student vertisement in the Jerusalem Post. -

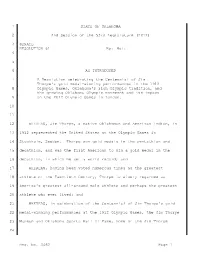

Sr61 Int.Pdf

1 STATE OF OKLAHOMA 2 2nd Session of the 53rd Legislature (2012) 3 SENATE RESOLUTION 61 By: Holt 4 5 6 AS INTRODUCED 7 A Resolution celebrating the Centennial of Jim Thorpe's gold medal-winning performances in the 1912 8 Olympic Games, Oklahoma's rich Olympic tradition, and the growing Oklahoma Olympic movement and its impact 9 on the 2012 Olympic Games in London. 10 11 12 WHEREAS, Jim Thorpe, a native Oklahoman and American Indian, in 13 1912 represented the United States at the Olympic Games in 14 Stockholm, Sweden. Thorpe won gold medals in the pentathlon and 15 decathlon, and was the first American to win a gold medal in the 16 decathlon, in which he set a world record; and 17 WHEREAS, having been voted numerous times as the greatest 18 athlete of the Twentieth Century, Thorpe is widely regarded as 19 America's greatest all-around male athlete and perhaps the greatest 20 athlete who ever lived; and 21 WHEREAS, in celebration of the Centennial of Jim Thorpe's gold 22 medal-winning performances at the 1912 Olympic Games, the Jim Thorpe 23 Museum and Oklahoma Sports Hall of Fame, home of the Jim Thorpe 24 Req. No. 3462 Page 1 1 Award, is featuring a special exhibit on the 1912 Olympics, 2 featuring artifacts from the 1912 games; and 3 WHEREAS, also in celebration of the Centennial of Jim Thorpe's 4 1912 Olympic performance, the Jim Thorpe Native American Games will 5 be held in Oklahoma City from June 10-17; and 6 WHEREAS, in commemoration of this anniversary of Oklahoma's 7 greatest Olympic achievement, the Oklahoma State Senate wishes to 8 honor Jim Thorpe's performances along with the achievements of the 9 15 Olympians in the Oklahoma Sports Hall of Fame, including John 10 Smith, Shannon Miller, Kenny Monday, J.W. -

Characterization of Popular Culture Icons in LIFE and TIME Magazines

STANLEY, MARSHICA., M.A. Characterization of Popular Culture Icons in LIFE and TIME Magazines. (2008) Directed by Dr. Rebecca Adams. 193 pp. Popular culture icons are physical objects of everyday use that make the everyday meaningful. They are ideas, both old and new, that are at the mercy of its viewer, meaning whatever the viewer desires whenever the viewers desires it. Celebrities with iconic images are global figures worshipped by the public. Their images appear to the public through the media and have their images transmitted globally through the media. No research currently examines the characteristics used to describe the idea of the icon in media. Research studies the use of stereotypes to depict women, racial minorities, as well as sporting individuals. The characterization of sporting individuals is frequently related to their gender or race. This research examines the differences in characterization of eight individuals with iconic images from the entertainment and sports industries in LIFE and TIME magazines. The eight individuals (Muhammad Ali, Babe Didrikson, Michael Jackson, Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley, Wilma Rudolph, Babe Ruth, and Oprah Winfrey) were selected based on the number of appearances they made in icon literature listing individuals as icons. Gender, race, and occupation differences are analyzed as well as trends in characterization over time. The individuals are also examined to determine which individuals have the most iconic images. Content analysis was conducted of magazine articles about the eight celebrities. The articles provide narratives about them as an ideal as opposed to them as a people. Results indicate that Whites, males, and entertainers have images that generally average more characteristics used to depict them to the public than Blacks, females, or sportsmen and women. -

Artistic Gymnastics Competition Shall Be Conducted in Accordance with the Regulations for the 30Th Summer Universiade 2019, Napoli

1 TABLES OF CONTENTS 2. Abbreviations 3. Contacts 4. General Information 4.1 General Competition Schedule 4.2 Athletes Villages 5. Competition Information 5.1 Technical Committee 5.2 Technical Regulations 5.3 Competition Format 5.4 Protests and Appeals 5.5 Sport Information Service 5.6 Sport Entries and Eligibility 5.7 Sport Equipment 6 Competition and Training Venues 7 Competition Schedule 7.1 Training Schedule 8 Technical Meetings 9 ITOs and NTOs 10 Doping Control 2 2. Abbreviations Abbreviations ACR ACCREDITATION AIR NAPLES INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT (CAPODICHINO) AVN1 ATHLETES’VILLAGE NAPOLI (MARITIME STATION) CD FISU DISCIPLINARY COMMITTEE CER CEREMONIES CF FISU FINANCIAL COMMITTEE CIC INTERNATIONAL CONTROL COMMITTEE CM FISU MEDICAL COMMITTEE CMC FISU MEDIA AND COMUNICATION COMMITTEE CMI FISU INTERNATIONAL MEDICAL COMMITTEE CSU FISU UNIVERSIADE SUPERVISION COMMITTEE CSU-E FISU SUMMER UNIVERSIADE SUPERVISION COMMITTEE CT FISU TECHNICAL COMMITTEE CTI (*) FISU INTERNATIONAL TECHNICAL COMMITTEE CTI-UE FISU INTERNATIONAL TECHNICAL SUB-COMMITTEE FOR THE SUMMER UNIVERSIADE DCO DOPING CONTROL OFFICER DEL DELEGATION SERVICES EC FISU EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE EMS EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES FIG FEDERATION INTERNATIONALE DE GYMNASTIQUE FISU FEDERATION INTERNATIONALE DU SPORT UNIVERSITAIRE FNB FOOD AND BEVERAGE FOP FIELD OF PLAY GMT GENERAL TECHNICAL MEETING GRS GAMES RESULTS SYSTEM HB HOST BROADCASTER HOD HEAD OF DELEGATION IR INTERNATIONAL REFEREE ISF INTERNATIONAL SPORT FEDERATION IT INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY ITO INTERNATIONAL TECHNICAL OFFICIAL MED MEDICAL -

2001 World Championships

1974 World Gymnastics Championships Varna, Bulgaria October 20-27, 1974 Men's Team 1. Japan 2. Soviet Union 3. German Democratic Republic 8. United States Men's All-Around 1. Shigeru Kasamatsu JPN 2. Nikolai Andrianov URS 3. Eizo Kenmotsu JPN 25. Wayne Young USA 26. Steve Hug USA 38. Gene Whelan * USA 41. Jay Whelan * USA 45. Brent Simmons * USA 57. Jim Ivicek * USA * prelims Men's Floor Exercise 1. Shigeru Kasamatsu JPN 2. Hiroji Kajiyama JPN 3. Andrei Keranov BUL Men's Pommel Horse 1. Zoltan Magyar HUN 2. Nikolai Andrianov URS 3. Eizo Kenmotsu JPN Men's Still Rings 1t. Nikolai Andrianov URS 1t. Danut Grecu ROM 3. Andrzej Szajna POL Men's Vault 1. Shigeru Kasamatsu JPN 2. Nikolai Andrianov URS 3. Hiroji Kajiyama JPN Men's Parallel Bars 1. Eizo Kenmotsu JPN 2. Nikolai Andrianov URS 3. Vladimir Marchenko URS Men's High Bar 1. Eberhard Gienger FRG 2. Wolfgang Thune GDR 3t. Eizo Kenmotsu JPN 3t. Andrzej Szajna POL Women's Team 1. Soviet Union 2. German Democratic Republic 3. Hungary 7. United States Women's All-Around 1. Ludmilla Tourischeva URS 2. Olga Korbut URS 3. Angelika Hellmann GDR 18. Joan Moore (Gnat) USA 26. Diane Dunbar USA 35. Janette Anderson USA 41. Debbie Fike* USA 42. Kathy Howard* USA 48. Ann Carr* USA * prelims Women's Vault 1. Olga Korbut URS 2. Ludmilla Tourischeva URS 3. Bozena Perdykulova TCH Women's Uneven Bars 1. Annelore Zinke GDR 2. Olga Korbut URS 3. Ludmilla Tourischeva URS Women's Balance Beam 1. Ludmilla Tourischeva URS 2. -

Las Aniluís, Un Aparato De La Gimnasia Artística M€Iscuüna

DEPARTAMENTO DE FÍSICA E EVSTALACIONES APLICADAS A LA EDIFICACIÓN AL MEDIO AMBIENTE Y AL URBANISMO E.T.S ARQUITECTURA INEF, MADRID UNIVERSIDAD POLITÉCNICA DE MADRID Las AnilUís, un aparato de la Gimnasia Artística M€iscuÜna Autor: Mariano García Carretero Ledo, en Ciencias de la Actividad Física y el Deporte Director: Santiago Coca Fernández Doctor, en Ciencias de la Información MADRID 2003 Tribunal nombrado por el Mgico. Y Excmo. Sr. Rector de la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, el día de de 2003 Presidente D. Vocal D. Vocal D. Vocal D. Secretario D. Realizado el acto de defensa y lectura de la tesis el día de de 2003 en Calificación: EL PRESIDENTE LOS VOCALES EL SECRETARIO Agradecimientos Este trabajo, no habría llegado al final sin la colaboración y consejo de las entidades y personas que me ayudaron a su elaboración. Es pues de justicia comenzar esta exposición con el reconocimiento a dichas entidades y personas. La U.P.M. que con sus cursos de doctorado me enseñó como debía iniciarse un trabajo de investigación. El INEF de Madrid que puso a mi disposición los medios materiales, ordenadores impresoras, papel asf como el material para las filmaciones. Los profesores: Enrique Navarro que me proporcionó el programa informático que hi2o posible el estudio técnico de los elementos analizados. Manuel Sillero sin cuya ayuda no hubiera sido posible realizar el estudio antropométrico. Javier Jiménez con sus conocimientos sobre la evolución de los aparatos de gimnasia. Todos aquellos profesores que respondieron a mis dudas puntuales sobre diversos aspectos de la tesis. El becario Francisco Miralles (Kiko) sin cuya colaboración esta tesis no se hubiera escrito. -

Torch Bearer

TORCH BEARER SOCIETY of 0 LYM PIC COLLECTORS YOUR COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN: Mrs Franceska Rapkin, Eaglewood, Oxhey Lane, Hatch End, Middx HA5 4AL Great Britain. SECRETARY: Mrs Elizabeth Miller, 258 Torrisholme Road Lancaster LA1 2TU, Great Britain. TREASURER: Colin Faers, 8 Farm Lane, West Lulworthi Dorset BH20 5SJ, Great Britain. AUCTION MANAGER: John Crowther, 3 Hill Drive, Handforth, Wilmslow, Cheshire SK9 3AP, Great Britain. LIBRARIAN: Ken Cook, 31 Thorn Lane, Rainham, Essex RM13 9S 1 , Great Britain. PACKET MANAGER: Bob Wilcock, 24 Hamilton Crescent, Brentwood, Essex CM14 5ES, Great Britain. P.R.O. Andy Potter, 75 Morley Avenue, Wood Green, London N22 6NG, Great Britain. BACK ISSUES AND John Miller, 258 Torrisholme Road, Lancaster DISTRIBUTION: LA1 2TU, Great Britain. EDITOR: Mrs Franceska Rapkin, Eaglewood, Oxhey Lane, Hatch End, Middx HA5 4AL, Great Britain. COMMITTEE: Robert Farley, Robert Kensit. **************************************************************** HACK ISSUES: At present, back issues of TORCH BEARER are still available to Volume 1, Issue 1, (March 1984), though there are now very few complete sets of Volume 1. When these run out, they will not be reprinted. It is Society policy to ensure that new members will be able to purchase back issues for a four year period, but we do not guarantee stocks for longer than this.Back issues cost £1.25 each, or f5.00 for a year's issues, including postage by surface mail. If ordering single copies, please indicate which volume you require.Cheques should be made payable to the SOCIETY OF OLYMPIC COLLECTORS and sent with the order to John Miller at the above address.If you wish to receive back issues by airmail, please add 60 pence per issue ( £2.40 per volume.) LIBRARY.