Recirculated Draft Environmental Impact Report RIMFOREST STORM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Resource Monitoring

Appendix 4 4a. Cultural Resources Assessment 4b. Paleontological Technical Memorandum CULTURAL RESOURCES ASSESSMENT FOR THE LAKE GREGORY DAM REHABILITATION PROJECT, SAN BERNARDINO COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Prepared for: Jennifer Lancaster Aspen Environmental Group 5020 Chesebro Road, Suite 200, Agoura Hills, CA 91301 On behalf of: County of San Bernardino, Special Districts Department 157 W. 5th Street, 2nd Floor, San Bernardino, CA 92415-0450 Authors: Dustin Keeler, Pam Daly, Tria Belcourt, Lynn Furnis, Ian Scharlotta and Sherri Gust Principal Investigator: Principal Architectural Historian: Tria Belcourt Pamela Daly Registered Professional Archaeologist October 2014 Revised June 2015 Project Number: 2861 Type of Study: Cultural Resources Assessment (Phase I) Sites: Lake Gregory Dam, LG2-001, 2861-1 (Apple Orchard Site) USGS Quadrangle: Silverwood Lake, Lake Arrowhead, San Bernardino North Survey Area: Dam: 28.08 acres Key Words: CEQA, EIR, Lake Gregory, Crestline, Lake Gregory Dam, LG2-001, 2861-1 (Apple Orchard Site) 1518 West Taft Avenue Field Offices cogstone.com Orange, CA 92865 San Diego • Riverside • Morro Bay • Oakland Toll free (888) 333-3212 Office (714) 974-8300 Federal Certifications 8(a), SDB, 8(m) WOSB State Certifications DBE, WBE, SBE, UDBE Lake Gregory Dam Rehabilitation Project TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................................... IV PURPOSE OF STUDY .............................................................................................................................................. -

Victorville OTSP

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Purpose of the Initial Study/Mitigated Negative Declaration ............................................. 1.0-1 1.2 Technical Studies .......................................................................................................................... 1.0-1 1.3 Abbreviations Used ...................................................................................................................... 1.0-2 2.0 PROJECT DESCRIPTION 2.1 Project Location and Setting ..................................................................................................... 2.0-1 2.2 Project Background and History ................................................................................................ 2.0-1 2.3 Project Objectives ........................................................................................................................ 2.0-2 2.4 Project Characteristics................................................................................................................. 2.0-4 2.5 Construction and Phasing .......................................................................................................... 2.0-8 3.0 ENVIRONMENTAL CHECKLIST 3.1 Background ................................................................................................................................... 3.0-1 3.2. Environmental Factors Potentially Affected ............................................................................ 3.0-3 3.3 Determination .............................................................................................................................. -

Hashmi Quazi, Phd, PE, GE Principal in Charge/Project Manager

Hashmi Quazi, PhD, PE, GE Principal in Charge/Project Manager Dr. Quazi has 31 years of experience providing geotechnical engineering services and has earned a reputation for providing quality work in an honest and ethical manner, on time and within budget. In his capacity as Principal in Charge or Project Manager, Dr. Quazi provides quality control, budget oversight, and technical assistance on various types of projects, including pipelines, wastewater treatment plants, reservoirs, and other related studies. He has supervised site investigations and prepared technical reports for facilities located in areas of high liquefaction potential and difficult subsurface conditions. Dr. Quazi is also responsible for the operation and management of our offices in Redlands, Monrovia, Costa EDUCATION Mesa, Palm Desert and Palmdale. Ph.D., Civil Engineering, University of Arizona, 1987 . M.S., Civil Engineering, Arizona State University, 1982 Relevant Experience . B.S., Bangladesh Engineering University, 1978 Pipelines REGISTRATIONS/CERTIFICATIONS La Sierra Pipeline (WMWD), Riverside County, CA. Principal . California, Civil Engineer, #46651 in Charge. Provides technical oversight and budget control for . California, Geotechnical Engineer, the geotechnical investigation report. The project consisted of #2517 approximately 21,000 linear feet of 24-inch diameter water pipeline, installed along La Sierra Avenue and the Riverside PROFESSIONAL MEMBERSHIPS County Flood Control Arlington Channel, Arizona Channel, . American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) and Line C-1 Channel. The alignment was located in the City . American Water Works Association of Riverside and the adjacent unincorporated portion of (AWWA) Riverside County, California. American Council of Engineering Companies (ACEC) Simpson Road Sewer Pipeline Repair (EMWD), Menifee, CA. Principal in Charge. -

Milebymile.Com Personal Road Trip Guide California State Highway #18

MileByMile.com Personal Road Trip Guide California State Highway #18 Miles ITEM SUMMARY 0.0 San Bernardino, CA Community of San Bernardino, California, a large city located in San -Junction of California Bernardino County, California, Attractions: Arrowhead Springs Hotel State Route #210/30 and Spa, a historic hotel & Spa located in the Arrowhead Springs neighborhood, Arrowhead geological monument, which is California Historical Landmark, Original McDonald's Site and Museum, SB Raceway Indoor Karting. Altitude: 1234 feet 2.9 Arrowhead Springs Road: Arrowhead Springs Road, Old Waterman Canyon Road, Campus Hot Springs Crusade for Christ, Arrowhead Springs Hot Lake, Altitude: 1788 feet 4.9 Cloudland Truck Trail Cloudland Truck Trail, Sweetwater Percolation Basin, Altitude: 2477 feet 11.3 Junction Junction California State Route #138, to, Crestline, California, a community in the San Bernardino Mountains of San Bernardino County, California, Lake Gregory Regional Park, Lake Gregory, a man-made lake and a county park Crestline, California, Altitude: 4390 feet 14.1 Squirrel Inn Squirrel Inn Road/California Route #189, N Road, Twin Pikes Road/California Route #189 Community Church, Calvary Chapel Conference Center, Blue Jay, California, a town in San Bernardino County, California. Altitude: 5144 feet 16.8 Daley Canyon Road: Daley Canyon Road, connects with California Route #189, Lake Country Club Arrowhead Country Club, Grass Valley Lake Park, State Route #173 traverses the Sand Bernardino Mountains, Blue Jay Bay, on Lake Arrowhead, a community in San Bernardino County, California, within the San Bernardino National Forest. Altitude: 5581 feet 17.2 Access Road: Robert Access Road, to, Robert Brownlee Observatory, an astronomical Brownlee Observatory observatory, located in Lake Arrowhead, California, just off California State Highway #18, Altitude: 5699 feet 18.2 California Route #173: California Route #173, to, Lake Arrowhead, California, a community in Lake San Bernardino County, California, within the San Bernardino National Forest. -

Outstanding Stale Dated Warrants Listing As Of: 11/20/2020

Outstanding Stale Dated Warrants Listing as of: 11/20/2020 Please Note: Requests to replace Stale Dated Warrants must be submitted and received by the Auditor-Controller's Office before the "Claim Deadline Date" (shown below) to be considered for reissuance. The county retains the right to deny any claims if filed after the "Claim Deadline Date". Government Code Section 29802. (a) Any warrant issued is void (stale) if not presented to the county treasurer for payment within six months after its date. (b) Any time within two years from the date on which the original warrant became void (stale), the payee or assignee of any stale dated warrant may present the warrant to the auditor to draw new warrants within the limitations prescribed by board resolution. (c) Any time after a period of two years from the date on which the original warrant became void (stale), the payee or assignee will need to present the warrant to the auditor to draw new warrants within the limitations prescribed by board resolution. Business Warrant Payee Payment Stale Dated Claim Deadline Payment Unit No. Name Date Date Date Amount Address CSARC 03432735 Napa Auto Parts 11/21/2016 05/23/2017 05/22/2021 $134.89 1323 West Florida Avenue, Hemet, CA 92543-3911 MHARC 03433493 Treatment Innovations 11/22/2016 05/24/2017 05/23/2021 $261.50 28 Westbourne Rd, Newton Centre, MA 02459 DPARC 03434701 Katie Smith 11/28/2016 05/30/2017 05/29/2021 $44.40 858 Oasis Village Ct, Blythe, CA 92225 TLARC 03435159 PEREZ NICANOR 11/28/2016 05/30/2017 05/29/2021 $2,351.95 46850 PALA RD, TEMECULA, -

Hazard Mitigation Plan

2020 Hazard Mitigation Plan Adoption Date: mm dd, 2020 Monte Vista Water District Justin Scott-Coe, General Manager 10575 Central Avenue Montclair, California 91763 Monte Vista Water District 2020 Hazard Mitigation Plan Table of Contents Section 1 Introduction ................................................................................... 4 1.1 Purpose of the Plan ................................................................................................ 4 1.2 Authority ................................................................................................................. 4 1.3 Community Profile .................................................................................................. 4 1.3.1 Physical Setting ....................................................................................... 4 1.3.2 History ...................................................................................................... 7 1.3.3 Demographics .......................................................................................... 8 1.3.4 Existing Land Use .................................................................................... 9 1.3.5 Development Trends .............................................................................. 11 Section 2 Plan Adoption .............................................................................. 12 2.1 Adoption by Local Governing Body ....................................................................... 12 2.2 Promulgation Authority ........................................................................................ -

Case 6:12-Bk-28006-MJ Doc 1627 Filed 08/27/15 Entered 08/27

Case 6:12-bk-28006-MJ Doc 1627 Filed 08/27/15 Entered 08/27/15 16:42:18 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 377 Case 6:12-bk-28006-MJ Doc 1627 Filed 08/27/15 Entered 08/27/15 16:42:18 Desc Main Document Page 2 of 377 City of San BernardinoCase 6:12-bk-28006-MJ - U.S. Mail Doc 1627 Filed 08/27/15 Entered 08/27/15 16:42:18 DescServed 8/20/2015 Main Document Page 3 of 377 @COMM DEPARTMENT 05321 100 PLAZA CLINICAL LAB INC 1458 - CELPLAN TECHNOLOGIES, INC. P O BOX 39000 100 UCLA MEDICAL PL 245 1920 ASSOCIATION DRIVE, 4TH FLOOR SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94139-5321 LOS ANGELES, CA 90024-6970 RESTON, VA 20191 3M CUSTOMER SERVICE A & G TOWING A & R LABORATORIES INC 2807 PAYSPHERE CIR 591 E 9TH ST 1401 RESEARCH PARK DR 100 CHICAGO, IL 60674 SAN BERNARDINO, CA 92410 RIVERSIDE, CA 92507 A & W EMBROIDERY A 1 AUTO GLASS A 1 BUDGET GLASS P O BOX 10926 671 VALLEY BL 705 S WATERMAN AV SAN BERNARDINO, CA 92423 COLTON, CA 92324 SAN BERNARDINO, CA 92408 A 1 BUDGET HOME & OFFICE CLEANING A 1 EVENT & PARTY RENTALS A 1 TREE SERVICE 2889 N GARDENA ST 251 E FRONT ST 304 E CLARK SAN BERNARDINO, CA 92407-6633 CORONA, CA 91723 REDLANDS, CA 92373 A A EQUIPMENT RENTAL A AMERICAN SELF STORAGE A G ENGINEERING 4811 BROOKS ST 875 E MILL ST 8647 HELMS AV MONTCLAIR, CA 91763 SAN BERNARDINO, CA 92408 RANCHO CUCAMONGA, CA 91730 A GRAPHIC ADVANTAGE A J JEWELRY A J O CONNOR LADDER 3901 CARTER AV 2 1292 W MILL ST 103 4570 BROOKS RIVERSIDE, CA 92501 SAN BERNARDINO, CA 92410-2500 MONTCLAIR, CA 91763 A K ENGINEERING A L WARD A PLUS AUTOMOTIVE INC 1254 S WATERMAN AV 17 ADDRESS REDACTED A PLUS SMOG AND MUFFLER SAN BERNARDINO, CA 92408 235 E HIGHLAND SAN BERNARDINO, CA 92404 A PLUS COURT REPORTERS INC A T & T A T S I 35 E UNION ST A 1265 VAN BUREN 180 8157 US HIGHWAY 50 PASADENA, CA 91103 ANAHEIM, CA 92807 ATHENS, OH 45701 A T SOLUTIONS INC A T SOLUTIONS INC. -

California Building Climate Zones

California Building Climate Zones Goos e Lake Legend Clear Lake Reservoir 96"! ¡¢ 101 Crescent City S# Yreka DEL NORTE S# MODOC Climate Zones SISKIYOU ¨¦§5 1 9 S# 97 Klamath ¤£ S# Alturas 2 10 S# Weed 3 11 S# Dunsmuir S# Lookout 4 12 5 13 LASSEN 395 Arcata S# Burney ¤£ S# QR299 Trinity 6 14 Lake 139 S# 89 Eureka Shasta QR QR Weaverville Lake S# 7 15 Eagl e Whiskeytown 299 QR Lake HUMBOLDT Lake S# Redding 8 16 S# Hayfork QR44 36 QR36 QR Susanville S# 1 S# Cottonwood Other Features S# S# QR36 Chester Westwood Honey Almanor Lake #S City Lake ¤£101 S# Red Bluff Roads TEHAMA County Line S# Teh ama PLUMAS Quincy S# Water Body S# Portola S# Paradise S# Chico S# Loyalton 11 BUTTE SIERRA GLENN Lake Oroville S# Willows Glenn Oroville Downieville MENDOCINO S# S# S# Fort Bra gg S# S# Willits S# 80 Soda Springs ¨¦§ Tah oe Vista S# Nevada City S#S# Kings Beach YUBA LAKE COLUSA S# Colusa PLACER Sutter NEVADA S# Lake S# Ukiah S# S#S# Marysville Williams Yuba City Tahoe Lakeport QR20 SUTTER S# Clearlake 70 16 S# South Lake Tahoe S# S# Clearlake QR Kelseyville 65 Point Arena S# 2 QR99 QR S# Auburn 70 S# Coloma S# Woodfords S# Cloverdale QR 50 5 Folsom YOLO 99 S# Roseville Placerville ¤£ ¨¦§ QR Lake S# S# Markleeville S# Citrus Heights EL DORADO S# Woodland ALPINE NAPA Lake 505 QR49 ¨¦§ 113 S# Sacramento Berry essa QR ^_ S# Saint Helena QR16 Santa Rosa AMADOR S# S# Dixon SACRAMENTO SONOMA S#Yountville Ione S# S# Jackson Napa S# Bridgeport S# SOLANO Camanche 101 Galt S# S# Reservoir MONO ¤£ Fairfield CALAVERAS S# San Andreas 12 QR S# New Hogan Murphys MARIN -

INITIAL STUDY/MITIGATED NEGATIVE DECLARATION LAKE ARROWHEAD COMMUNITY SERVICES DISTRICT BLUE JAY WELL SITE PROJECT N0. 187 Lake

INITIAL STUDY/MITIGATED NEGATIVE DECLARATION LAKE ARROWHEAD COMMUNITY SERVICES DISTRICT BLUE JAY WELL SITE PROJECT N0. 187 Lake Arrowhead, California (San Bernardino County) Prepared for: LAKE ARROWHEAD COMMUNITY SERVICES DISTRICT 27307 CA-189 Blue Jay, California 92317 Prepared by: CHAMBERS GROUP, INC. 5 Hutton Centre Drive, Suite 750 Santa Ana, California 92707 (949) 261-5414 November 2020 Blue Jay Well Site Project, Lake Arrowhead, San Bernardino County, California TABLE OF CONTENTS Page SECTION 1.0 – PROJECT DESCRIPTION AND ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING ............................................... 5 1.1 PROJECT BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE ....................................................................................... 5 1.2 PROJECT LOCATION AND SITE CHARACTERISTICS ........................................................................ 5 1.3 PROPOSED ACTIVITIES .................................................................................................................. 5 1.3.1 Project Schedule .............................................................................................................. 8 1.4 REQUIRED PERMITS AND APPROVALS........................................................................................ 10 1.4.1 Responsible Agencies ..................................................................................................... 10 SECTION 2.0 – ENVIRONMENTAL DETERMINATION ........................................................................... 11 2.1 ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS POTENTIALLY AFFECTED: ............................................................. -

Appendix H: Water, Wastewater, and Hydrology Existing Conditions

SAN BERNARDINO COUNTYWIDE PLAN DRAFT PEIR COUNTY OF SAN BERNARDINO Appendices Appendix H: Water, Wastewater, and Hydrology Existing Conditions June 2019 SAN BERNARDINO COUNTYWIDE PLAN DRAFT PEIR COUNTY OF SAN BERNARDINO Appendices This page intentionally left blank. PlaceWorks DRAFT County of San Bernardino General Plan Water, Wastewater, and Hydrology Existing Conditions Prepared for: County of San Bernardino Prepared by: 40-004 Cook Street, Suite 4 Palm Desert, California 92211 Contact: Charles Greely in collaboration with: 3 MacArthur Place, Suite 1100 Santa Ana, California 92707 Contact: Colin Drukker MAY 2017 This reportDRAFT was prepared to inform the Countywide Plan and is not intended to be continuously updated. H-1 INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK DRAFT H-2 DRAFT SAN BERNARDINO COUNTYWIDE PLAN WATER, HYDROLOGY, AND WASTEWATER EXISTING CONDITIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page No. 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...............................................................................................1 1.1 Water Supply .......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Wastewater Services ............................................................................................... 1 1.3 Drainage and Flooding / Surface Water .................................................................. 7 1.4 Groundwater Management...................................................................................... 7 1.5 Groundwater Quality ............................................................................................. -

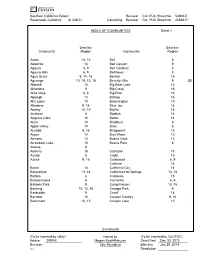

(U 338-E) Cancelling Revised Cal. PUC Sheet No

Southern California Edison Revised Cal. PUC Sheet No. 53902-E Rosemead, California (U 338-E) Cancelling Revised Cal. PUC Sheet No. 45848-E* INDEX OF COMMUNITIES Sheet 1 Baseline Baseline Community Region Community Region Acton 14, 16 Bell 8 Adelanto 14 Bell Canyon 9 Agoura 6, 9 Bell Gardens 8 Agoura Hills 6, 9 Bellflower 8 Agua Dulce 9, 14, 16 Benton 16 Aguanga 10, 14, 15, 16 Beverly Hills 9 (D) Alberhill 10 Big Bear Lake 16 Alhambra 9 Big Creek 16 Aliso Viejo 6, 8 Big Pine 16 Alpaugh 13 Bishop 16 Alta Loma 10 Bloomington 10 Altadena 9, 16 Blue Jay 16 Amboy 14, 15 Blythe 15 Anaheim 8 Bodfish 16 Angelus Oaks 16 Boron 14 Anza 10 Bradbury 9 Apple Valley 14 Brea 8 Arcadia 9, 16 Bridgeport 16 Argus 14 Bryn Mawr 10 Armona 13 Buena Vista 13 Arrowbear Lake 16 Buena Park 8 Artesia 8 Auberry 16 Cabazon 15 Avalon 6 Cadiz 15 Azusa 9, 16 Calabasas 6, 9 Caliente 16 Baker 14 California City 14 Bakersfield 13, 16 California Hot Springs 13, 16 Balboa 6 Calimesa 10 Balboa Island 6 Camarillo 6, 9 Baldwin Park 9 Camp Nelson 13, 16 Banning 10, 15, 16 Canoga Park 9 Bardsdale 9 Cantil 14 Barstow 14 Canyon Country 9, 16 Beaumont 10, 15 Canyon Lake 10 (Continued) (To be inserted by utility) Issued by (To be inserted by Cal. PUC) Advice 2990-E Megan Scott-Kakures Date Filed Dec 30, 2013 Decision Vice President Effective Jan 29, 2014 1C8 Resolution Southern California Edison Revised Cal. PUC Sheet No. -

AIR TRAFFIC INITIAL ENVIRONMENTAL REVIEW Page

AIR TRAFFIC INITIAL ENVIRONMENTAL REVIEW JO 7400.2 Western Service Center Facility: Date: May 2019 Operations Support Group Ryan Weller Prepared by: Phone: (206) 231-2286 AJV-W25 ===================================================================== NOTE: This initial environmental review provides basic information about the proposed action to better assist in preparing for the environmental analysis phase. Although it requests information in several categories, not all the data may be available initially; however, it does represent information, in accordance with FAA Order 1050.1, Environmental Impacts: Policies and Procedures, which ultimately will be needed for preparation of the appropriate environmental document. If the Instrument Flight Procedure (IFP) Environmental Pre-Screening Filter Tool (EFPT) was used to initiate the environmental review process, this form is not required. Section 1: Proposed Project Description Describe the proposed project. Include general information identifying procedure(s) and/or airspace action(s) to be implemented and/or amended. Identify the associated airports and/or facilities. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) proposes the creation of the JCKIE TWO Area Navigation (RNAV) Standard Terminal Arrival Route (STAR) at Ontario International Airport (ONT), in Ontario, California. In addition, the existing Required Navigation Performance (RNPs) to Runway 26 will be adjusted to accommodate the JCKIE TWO STAR. This arrival procedure, also referred to as “JCKIE TWO STAR”, is the proposed action (Proposed Action) for this Initial Environmental Review (IER); the details of the Proposed Action are provided below. The proposed JCKIE TWO STAR procedure at ONT was designed with RNAV and Global Position System (GPS) navigation, which enables a precise and repeatable path for aircraft. The FAA identified an opportunity to consolidate two routes, provide the required separation from other air traffic routes and address community concerns regarding aircraft overflights.