Riccardo Muti Conductor Honegger Pacific 231 Bates Alternative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Music as Representational Art Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1vv9t9pz Author Walker, Daniel Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Volume I Music as Representational Art Volume II Awakening A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Daniel Walker 2014 © Copyright by Daniel Walker 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Volume I Music as Representational Art Volume II Awakening by Daniel Walker Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Ian Krouse, Chair There are two volumes to this dissertation; the first is a monograph, and the second is a musical composition, both of which are described below. Volume I Music is a language that can be used to express a vast range of ideas and emotions. It has been part of the human experience since before recorded history, and has established a unique place in our consciousness, and in our hearts by expressing that which words alone cannot express. ii My individual interest in the musical language is its use in telling stories, and in particular in the form of composition referred to as program music; music that tells a story on its own without the aid of images, dance or text. The topic of this dissertation follows this line of interest with specific focus on the compositional techniques and creative approach that divide program music across a representational spectrum from literal to abstract. -

Musical Hybridization and Political Contradiction: the Success of Arthur Honeggerâ•Žs Antigone in Vichy France

Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research Volume 7 2021 Musical Hybridization and Political Contradiction: The Success of Arthur Honegger’s Antigone in Vichy France Emma K. Schubart University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/bjur Recommended Citation Schubart, Emma K. (2021) "Musical Hybridization and Political Contradiction: The Success of Arthur Honegger’s Antigone in Vichy France," Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research: Vol. 7 , Article 4. Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/bjur/vol7/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUTLER JOURNAL OF UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH, VOLUME 7 MUSICAL HYBRIDIZATION AND POLITICAL CONTRADICTION: THE SUCCESS OF ARTHUR HONEGGER’S ANTIGONE IN VICHY FRANCE EMMA K. SCHUBART, UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, CHAPEL HILL MENTOR: SHARON JAMES Abstract Arthur Honegger’s modernist opera Antigone appeared at the Paris Opéra in 1943, sixteen years after its unremarkable premiere in Brussels. The sudden Parisian success of the opera was extraordinary: the work was enthusiastically received by the French public, the Vichy collaborationist authorities, and the occupying Nazi officials. The improbable wartime triumph of Antigone can be explained by a unique confluence of compositional, political, and cultural realities. Honegger’s compositional hybridization of French and German musical traditions, as well as his opportunistic commercial motivations as a Swiss composer working in German-occupied France, certainly aided the success of the opera. -

SFS-Media-Mason-Bates-Grammy

Press Contacts: Public Relations National Press Representation: San Francisco Symphony Shuman Associates (415) 503-5474 (212) 315-1300 [email protected] [email protected] www.sfsymphony.org/press FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE / December 6, 2016 (High resolution images available for download from the SFS Media’s Online Press Kit) MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS AND THE SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY’S RECORDING OF MASON BATES: WORKS FOR ORCHESTRA NOMINATED FOR 2017 GRAMMY AWARD Recording on Orchestra’s in-house label SFS Media nominated for Best Orchestral Performance SAN FRANCISCO, December 6, 2016 – Music Director Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony’s live concert recording of works by Bay Area composer Mason Bates was nominated for a 2017 Grammy® Award today in the category of Best Orchestral Performance. Mason Bates: Works for Orchestra was released in March 2016 and features the first recordings of the SFS-commissioned The B-Sides and Liquid Interface, in addition to Alternative Energy. These three works illustrate Bates’s exuberantly inventive music that expands the symphonic palette with sounds of the digital age: techno, drum ‘n’ bass, field recordings and more, with the composer performing on electronica. MTT and the SFS have championed Bates’s works for over a decade, evolving a partnership built on multi-year commissioning, performing, recording, and touring projects. Click here to watch a video about Mason Bates: Works for Orchestra. "I never cease to be astonished by the San Francisco Symphony's impact on American music,” stated Mason Bates this morning. “Their performances of living legends, from Lou Harrison to John Adams, have continually thrilled and educated me. -

Reinhardt's Choice: Some Alternatives to Weill?

DAVID DREW Reinhardt's Choice: Some Alternatives to Weill? The pretexts for the present paper are the author's essays >Der T#g der Ver heissung and the Prophecies of jeremiah<, Tempo, 206 (October 1998), 11- 20, and >Der T#g der Verheissung: Weill at the Crossroads<, 1impo, 208 (April 1999), 335-50. As suggested in the preface to the second essay, the paper is intended to function both as a free-standing entity and as an extended bridge between the last section of the earlier essay and the first section of its successor. According to Meyer Weisgal's detailed account of the origins of The Eter nal Road, Reinhardt had no inkling of his plans until their November 1933 meeting in Paris.1 Weisgal began by outlining the idea of a biblical drama that would for the first time evoke the Old Testan1ent in all its breadth rather than in isolated episodes. At the end of his account, according to Weisgal, Reinhardt sat motionless and in silence before saying »very sim ply<< »But who will be the author of this biblical play and who will write the mu sic?<< . »You are the master<< , I said, ••It is up to you to select them<<. Again there was a long uncomfortable pause and Reinhardt said that he would ask Franz Werfel and Kurt Weill to collaborate with him. With or without prior notice2, the problems inherent in Weisgal's com mission were so complex that Reinhardt would have had good reason for Meyer W. Weisgal, >Beginnings of The Eternal Road<, in: T"he Etemal Road (New York 1937 - programme-book for the production by MWW and Crosby Gaige at the Man hattan Opera House), pp. -

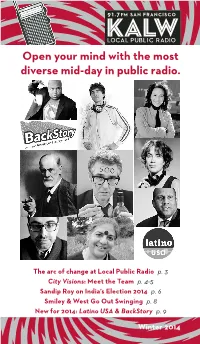

Open Your Mind with the Most Diverse Mid-Day in Public Radio

Open your mind with the most diverse mid-day in public radio. The arc of change at Local Public Radio p. 3 City Visions: Meet the Team p. 4-5 Sandip Roy on India’s Election 2014 p. 6 Smiley & West Go Out Swinging p. 8 New for 2014: Latino USA & BackStory p. 9 Winter 2014 KALW: By and for the community . COMMUNITY BROADCAST PARTNERS AIA, San Francisco • Association for Continuing Education • Berkeley Symphony Orchestra • Burton High School • East Bay Express • Global Exchange • INFORUM at The Commonwealth Club • Jewish Community Center of San Francisco • LitQuake • Mills College • New America Media • Oakland Asian Cultural Center • Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at UC Berkeley • Other Minds • outLoud Radio Radio Ambulante • San Francisco Arts Commission • San Francisco Conservatory of Music • San Quentin Prison Radio • SF Performances • Stanford Storytelling Project • StoryCorps • Youth Radio KALW VOLUNTEER PRODUCERS Rachel Altman, Wendy Baker, Sarag Bernard, Susie Britton, Sarah Cahill, Tiffany Camhi, Bob Campbell, Lisa Carmack, Lisa Denenmark, Maya de Paula Hanika, Julie Dewitt, Matt Fidler, Chuck Finney, Richard Friedman, Ninna Gaensler-Debs, Mary Goode Willis, Anne Huang, Eric Jansen, Linda Jue, Alyssa Kapnik, Carol Kocivar, Ashleyanne Krigbaum, David Latulippe, Teddy Lederer, JoAnn Mar, Martin MacClain, Daphne Matziaraki, Holly McDede, Lauren Meltzer, Charlie Mintz, Sandy Miranda, Emmanuel Nado, Marty Nemko, Erik Neumann, Edwin Okong’o, Kevin Oliver, David Onek, Joseph Pace, Liz Pfeffer, Marilyn Pittman, Mary Rees, Dana Rodriguez, -

The Audiophile Voice

Children-Adam_Graves_11-1_master_color.qxd 10/16/2019 4:26 PM Page 2 George Graves Classical Mason Bates Children of Adam Ralph Vaugh Williams Dona Nobis Pacem Richmond Symphony; Steven Smith, Cond. Michelle Areyzaga, soprano; Kevin Deas, bass-baritone Reference Recording / Fresh FR-732 IWAS BORN in Richmond, A, and In the 1970s and early ‘80s, my northward in order to visit even though my family moved to college roommate was still attend - Washington, D.C. to hear the Northern Virginia when I was three ing the university in Richmond, National Symphony Orchestra per - years old (just outside the DC working toward his eventual doctor - form or to attend one of the many “Beltway”), my relatives remained ate in psychology, so my yearly visit weekly concerts of the President’s in Richmond, and we used to visit to my parents also included a visit Army, Navy, Marine Corps or Air them often as I was growing up. to my ex-roommate. Force symphonic bands. I had heard When I graduated college and I had heard my “roomie” com - that Richmond had a civic sympho - moved to California, my father plain on the phone for a number of ny orchestra, and my friend started retired and he and my mother years about what a musical waste - to laugh when I asked him about it. moved back to Richmond. So, as an land Richmond was in those days. “They’re terrible,” was his reply. adult, when I visited my parents, it He often talked about having to “My high school band played bet - was there that I visited them. -

North Carolina Symphony Tours to Washington, D.C

North Carolina Symphony Tours to Washington, D.C. for SHIFT Festival Subject: North Carolina Symphony Tours to Washington, D.C. for SHIFT Festival From: Meredith Laing <[email protected]> Date: Wed, 15 Mar 2017 14:51:15 +0000 To: Meredith Laing <[email protected]> Dear friends, In just two weeks, the North Carolina Symphony will depart for Washington, D.C., to par>cipate in the inaugural year of SHIFT: A Fes+val of American Orchestras. NCS is one of just four U.S. orchestras selected for this na>onal fes>val! We will bring music with direct connec>ons to North Carolina to our na>on’s capital, and the programs will be previewed in Raleigh. Details about the SHIFT fes>val and the preview concerts are below and aFached. Thank you for your support of the North Carolina Symphony as we embark on this adventure with the privilege of represen>ng our state! All the best, Meredith -- Meredith Kimball Laing Director of Communications North Carolina Symphony 3700 Glenwood Avenue, Suite 130 Raleigh, NC 27612 919.789.5484 www.ncsymphony.org Experience the Power of Live Music Join Us for Upcoming Concerts Learn How We Serve North Carolina Read Our Report to the Community Support Your Symphony Make a Donation FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT Meredith Kimball Laing 919.789.5484 [email protected] North Carolina Symphony Tours to Washington, D.C. as One of Four Orchestras Chosen for SHIFT: A Festival of American Orchestras 1 of 5 4/20/17, 4:08 PM North Carolina Symphony Tours to Washington, D.C. -

An Analysis of Honegger's Cello Concerto

AN ANALYSIS OF HONEGGER’S CELLO CONCERTO (1929): A RETURN TO SIMPLICITY? Denika Lam Kleinmann, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2014 APPROVED: Eugene Osadchy, Major Professor Clay Couturiaux, Minor Professor David Schwarz, Committee Member Daniel Arthurs, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies James Scott, Dean of the School of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kleinmann, Denika Lam. An Analysis of Honegger’s Cello Concerto (1929): A Return to Simplicity? Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2014, 58 pp., 3 tables, 28 examples, 33 references, 15 titles. Literature available on Honegger’s Cello Concerto suggests this concerto is often considered as a composition that resonates with Les Six traditions. While reflecting currents of Les Six, the Cello Concerto also features departures from Erik Satie’s and Jean Cocteau’s ideal for French composers to return to simplicity. Both characteristics of and departures from Les Six examined in this concerto include metric organization, thematic and rhythmic development, melodic wedge shapes, contrapuntal techniques, simplicity in orchestration, diatonicism, the use of humor, jazz influences, and other unique performance techniques. Copyright 2014 by Denika Lam Kleinmann ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………………..iv LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES………………………………………………………………..v CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION………..………………………………………………………...1 CHAPTER II: HONEGGER’S -

Paris, 1918-45

un :al Chapter II a nd or Paris , 1918-45 ,-e ed MARK D EVOTO l.S. as es. 21 March 1918 was the first day of spring. T o celebrate it, the German he army, hoping to break a stalemate that had lasted more than three tat years, attacked along the western front in Flanders, pushing back the nv allied armies within a few days to a point where Paris was within reach an oflong-range cannon. When Claude Debussy, who died on 25 M arch, was buried three days later in the Pere-Laehaise Cemetery in Paris, nobody lingered for eulogies. The critic Louis Laloy wrote some years later: B. Th<' sky was overcast. There was a rumbling in the distance. \Vas it a storm, the explosion of a shell, or the guns atrhe front? Along the wide avenues the only traffic consisted of militarr trucks; people on the pavements pressed ahead hurriedly ... The shopkeepers questioned each other at their doors and glanced at the streamers on the wreaths. 'II parait que c'ctait un musicicn,' they said. 1 Fortified by the surrender of the Russians on the eastern front, the spring offensive of 1918 in France was the last and most desperate gamble of the German empire-and it almost succeeded. But its failure was decisive by late summer, and the greatest war in history was over by November, leaving in its wake a continent transformed by social lb\ convulsion, economic ruin and a devastation of human spirit. The four-year struggle had exhausted not only armies but whole civiliza tions. -

Honegger Pastorale D’Été Symphony No

HONEGGER PASTORALE D’ÉTÉ SYMPHONY NO. 4 UNE CANTATE DE NOËL VLADIMIR JUROWSKI conductor CHRISTOPHER MALTMAN baritone LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA and CHOIR NEW LONDON CHILDREN’S CHOIR 0058 Honegger booklet.indd 1 8/23/2011 10:24:50 AM HONEGGER PASTORALE D’ÉTÉ (SUMMER PASTORAL) Today the Swiss-born composer Arthur of birdsong on woodwind place Honegger Honegger is often remembered as a member more amongst the 19th-century French of ‘Les Six’ – that embodiment of 1920s landscape painters than les enfants terribles. Parisian modernist chic in music. How unjust. From this, Pastorale d’été builds to a rapturous It is true that for a while Honegger shared climax then returns – via a middle section some of the views of true ‘Sixists’ like Francis that sometimes echoes the pastoral Vaughan Poulenc and Darius Milhaud, particularly Williams – to the lazy, summery motion of when they were students together at the Paris the opening. Conservatoire. But even from the start he Stephen Johnson could not share his friends’ enthusiasm for the eccentric prophet of minimalism and Dadaism, Eric Satie, and he grew increasingly irritated with the group’s self-appointed literary SYMPHONY NO. 4 apologist, Jean Cocteau. It was soon clear that, despite the dissonant, metallic futurism of By the time Honegger came to write his Fourth works like Pacific 231 (1923), Honegger had Symphony in 1946, he was barely recognizable more respect for traditional forms and for as the former fellow traveller of the wilfully romantic expression than his friends could provocative Les Six. He had moved away from accept. Poulenc and Milhaud both dismissed any desire to shock or scandalize audiences: Honegger’s magnificent ‘dramatic psalm’ Le Roi instead, like Mozart, he strove ‘to write music David (‘King David’, 1923) as over-conventional. -

Ian Davidson, Composer

TEXAS STATE VITA I. Academic/Professional Background A. Name: Ian Bruce Davidson Title: Regents’ Professor B. Educational Background Degree Year University Major Thesis/Dissertation DMA 1997 University of Texas Music – Oboe “The Use of the Oboe and Oboe D’Amore at Austin Performance in selected works of J.S. Bach” MM 1983 University of Texas Music – Oboe Masters Oboe Performance Recital at Austin Performance BM 1980 DePauw University Music – Oboe Oboe Performance Senior Recital Performance C. University Experience Position University Dates Regents’ Professor Texas State University System Foundation 2014-Present University Distinguished Professor Texas State University – San Marcos 2014-Present Professor Texas State University – San Marcos 2008-2014 Associate Professor Texas State University – San Marcos 2003-2008 Assistant Professor Texas State University – San Marcos 1997-2003 Instructor Texas State University – San Marcos 1993-1997 Lecturer Texas State University – San Marcos 1991-1993 Visiting Lecturer University of Texas at Austin 1995-1996 Lecturer Southwestern University 1989-1992 D. Relevant Professional Experience Position Entity Dates English Horn and Associate Principal Oboe Austin Symphony Orchestra 1984-Present English Horn and Assistant Principal Oboe Austin Lyric Opera Orchestra 1988-Present Oboist and Founding Member Wild Basin Winds 1996-Present Assistant Principal and Utility Oboe Santa Fe Opera Orchestra 1996-1998 Principal Oboe Dallas Bach Orchestra 1988-1998 II. TEACHING A. Teaching Honors and Awards: 1) Presidential Awards 2004 – Departmental Nominee – Teaching 2003 – Departmental Nominee – Teaching 1999 – Departmental Nominee – Teaching 2) Alpha Chi Honor Society 2004 – Alpha Chi Honor Society – Favorite Professor 2002 – Alpha Chi Honor Society – Favorite Professor B. Courses Taught: 1) Oboe – All Levels 2) MU2313 – “Introduction to Fine Arts” 3) MU1312 – “Essential Musicianship” 4) MU1212 – “Theory II 5) MU2104 – “Writing About Music” 6) MU1000-MU4000 – “Departmental Convocation” C. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 129, 2009-2010

— BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA James Levine, Music Director Bernard Haitink, Conductor Emeritus Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Laureate 129th Season, 2009-2010 €r*<& CHAMBER TEA I Friday, October 30, at 2:30 COMMUNITY CONCERT I Sunday, November 1, at 3, at First Church in Dedham This concert is supported by the Dedham Institution for Savings Foundation, in memory of R. Willis Leith, Jr. COMMUNITY CONCERT II Sunday, November 8, at 3, at Blessed Mother Teresa Parish, Dorchester These free concerts are made possible by a generous grant from The Lowell Institute. SHEILA FIEKOWSKY, violin (1st violin in Honegger) BO YOUP HWANG, violin (1st violin in Beethoven) RACHEL FAGERBURG, viola ALEXANDRE LECARME, cello HONEGGER Quartet No. 2 in D Allegro Adagio Allegro marcato BEETHOVEN String Quartet No. 10 in E-flat, Opus 74, Harp Poco adagio—Allegro Adagio ma non troppo Presto—Piu presto quasi andantino—Tempo I Allegretto con variazioni Week5 Arthur Honegger (1892-1955) Quartet No. 2 in D Arthur Honegger was born in Le Havre, France, to Swiss parents, and grew up there. In 1913 he moved with his family to Zurich, where he attended the Conservatory for two years before moving to Paris to study at the Conservatory there in a range of musical subjects, including violin. While there he got to know his fellow students Germaine Tailleferre, Georges Auric, and Darius Milhaud, all of whom would later be lumped together as "Les nouveaux jeunes" and later (along with Francis Poulenc and Louis Durey) "Les Six" in association with Satie and Cocteau, although the interests of the individual composers soon outstripped allegiance to the group.