9780718894351 Text Mee.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gladstone Review

SAMPLE ARTICLES FROM THE GLADSTONE REVIEW As it is likely that several readers of this e-journal have discovered the existence of the New Gladstone Review for the first time, I thought it would be helpful to give more idea of the style adopted by providing some examples of articles that were published during 2017. I begin with the introduction on page 1 of the January 2017 issue, and thereafter add seven articles published in subsequent issues. THE GLADSTONE REVIEW January 2017 a monthly e-journal Informal commentary, opinions, reviews, news, illustrations and poetry for bookish people of philanthropic inclination INTRODUCTION This is the first issue of the successor to the Gladstone Books Newsletter, the publication which was launched in November 2015 in association with the Gladstone Books shop in Southwell. The shop was named after William Gladstone, who became an MP for near-by Newark when only 23 years old in 1832, and was subsequently Liberal Prime Minister on four occasions until his death in 1898. It was Gladstone's bibliophilia, rather than his political achievements, that led to adoption of this name when I first started selling second-hand books in Newark in 2002. For he was an avid reader of the 30,000 books he assembled in his personal library, which became the nucleus of the collection in St Deiniol’s library in north Wales, and which is his most tangible legacy. I retained the name when moving the business to Lincoln in 2006, and since May 2015, to the shop in Southwell. * Ben Mepham * Of course, Gladstone Books is now back in Lincoln! Zygmunt Bauman (1925-2017): an obituary The name of Zygmunt Bauman, who died last month, while largely unknown to the general public, reputedly induced a state of awe among his fellow sociologists. -

NARRATIVE, RELIGION and SCIENCE Fundamentalism Versus Irony –

NARRATIVE, RELIGION AND SCIENCE Fundamentalism versus Irony – STEPHEN PRICKETT PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CBRU,UK West th Street, New York, NY -, USA Stamford Road, Oakleigh, VIC , Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ , Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town , South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Stephen Prickett This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Baskerville Monotype /. pt. System LATEX ε [TB] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication data Prickett, Stephen. Narrative, religion and science : Fundamentalism versus Irony, – / by Stephen Prickett. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. Narration (Rhetoric) . Literature and science. Religion and literature. I. Title. PN.P – dc ISBN hardback ISBN paperback Contents Acknowledgements page vii Introduction: Arthur Dent, Screwtape and the mysteries of story-telling Postmodernism, grand narratives and just-so stories Postmodernism and grand narratives Just-so stories Narrative and irony Language, culture and reality Newton and Kissinger: -

BBS 141 2019 Apr

ISSN 0960-7870 BRITISH BRICK SOCIETY INFORMATION 141 APRIL 2019 OFFICERS OF THE BRITISH BRICK SOCIETY Chairman Michael Chapman 8 Pinfold Close Tel: OH 5-965-2489 Woodborough E-mail: [email protected] NOTTINGHAM NG14 6DP Honorary Secretary Michael S. Oliver 19 Woodcroft Avenue Tel. 020-8954-4976 STANMORE E-mail: [email protected] Middlesex HA7 3PT Honorary Treasurer Graeme Perry 62 Carter Street Tel: 07773-406201 UTTOXETER E-mail: [email protected] Staffordshire STU 8EU Enquiries Secretary Michael Hammett 9 Bailey Close and Liason Officer with the BAA HIGH WYCOMBE Tel: 01494-520299 Buckinghamshire HP 13 6QA E-mail: [email protected] Membership Secretary Dr Anthony A. Preston 11 Harcourt Way (Receives all direct subscriptions, £12-00per annum*) SELSEY, West Sussex PO20 OPF Tel: 01243-607628 Editor of BBS Information David H. Kennett 7 Watery Lane (Receives all articles and items for BBS Information) SHIPSTON-ON-STOUR Tel: 01608-664039 Warwickshire CV36 4BE E-mail: [email protected] Web Officer Richard Harris Weald and Downland Museum E-mail [email protected] Singleton CHICHESTER West Sussex The society's Auditor is: Adrian Corder-Birch DL Rustlings, Howe Drive Tel: 078616-362607 HALSTEAD, E-mail: [email protected] Essex CO9 2QL * The annual subscription to the British Brick Society is £12-00 per annum. Telephone numbers and e-mail addresses of members would be helpful for contact purposes, but these will not be included in the Membership List. British Brick Society web site: http://britishbricksoc.co.uk Contents Editorial: Looking Back, Looking Forward ............................................................... 2 Ripon in Prospect by David H. -

Science a Childrens Encyclopedia PDF Book

SCIENCE A CHILDRENS ENCYCLOPEDIA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK DK | 304 pages | 01 Aug 2014 | Dorling Kindersley Ltd | 9781409347927 | English | London, United Kingdom Science A Childrens Encyclopedia PDF Book It's designed for advanced elementary and middle school students, as the language is more complex and the explanations more complicated than those in the Kingfisher and DK Publishing survey encyclopedias. The Dog Encyclopedia for Kids. Everyone wants their kids to be smart. First Science Encyclopedia : Also from DK Publishing, the First Science Encyclopedia is geared toward younger kids and aims to spark an early interest in science and the natural world. The sale of the encyclopedia was then banned, although it was already out of print by that time. Engaging for new and pre-readers Covers sports and hobbies Short bios of great thinkers. A picture encyclopedia may be the best choice for young children. In recent years the company has gone digital and expanded its offerings into a host of subscription services. Children's literature portal. The book weighs in at pages and is a light companion to the more comprehensive Encyclopedia of Science. March 05, This list represents an embarrassment of riches, as virtually every book we included is fantastic in its own right. The Usborne Science Encyclopedia : Recognizing that kids' reference books can no longer compete with the Web, the Usborne volume has a handy section of recommended Internet sites that might help kids with further research. Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Book of Knowledge. By the s the binding is brown in colour, and displays a flaming torch on each book's spine. -

Jack Clemo 1916-55: the Rise and Fall of the 'Clay Phoenix'

1 Jack Clemo 1916-55: The Rise and Fall of the ‘Clay Phoenix’ Submitted by Luke Thompson to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English In September 2015 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. 2 Abstract Jack Clemo was a poet, novelist, autobiographer, short story writer and Christian witness, whose life spanned much of the twentieth century (1916- 1994). He composed some of the most extraordinary landscape poetry of the twentieth century, much of it set in his native China Clay mining region around St Austell in Cornwall, where he lived for the majority of his life. Clemo’s upbringing was one of privation and poverty and he was famously deaf and blind for much of his adult life. In spite of Clemo’s popularity as a poet, there has been very little written about him, and his confessional self-interpretation in his autobiographical works has remained unchallenged. This thesis looks at Clemo’s life and writing until the mid-1950s, holding the vast, newly available and (to date) unstudied archive of manuscripts up against the published material and exploring the contrary narratives of progressive disease and literary development and success. -

Childrens Encyclopedia Free Ebook

FREECHILDRENS ENCYCLOPEDIA EBOOK Various | 320 pages | 01 Apr 2017 | Usborne Publishing Ltd | 9781409577669 | English | London, United Kingdom “Children's encyclopedia with QR links” at Usborne Children’s Books Creating a more engaging and fun learning experience for students, the activities in Britannica Fundamentals align with the content areas children learn in Childrens Encyclopedia classroom. From language Childrens Encyclopedia literacy to geography and mathematics, Britannica Fundamentals supports classroom curriculum while also building digital literacy. Switch Level. Kids Students Scholars. Explore Fundamentals. Animal Kingdom. Childrens Encyclopedia Atlas. Can You Guess? Compare Countries. When Are Volcanoes Safe? Volcanoes have four states: active has erupted in the past 10, yearserupting is experiencing an eruptiondormant has the potential to erupt againand extinct has not erupted in over 10, years. See also: volcanoMauna Loa. On This Day. Strait of Magellan. In Childrens Encyclopedia Magellan and three Spanish ships entered the strait later named for him, sailing between the mainland tip of South America and the island of Tierra del Fuego toward the Childrens Encyclopedia. Read More. Sign up for our Britannica for Parents newsletter for expert advice on parenting in the 21st century! Childrens Encyclopedia you for subscribing! Be Childrens Encyclopedia the look out for the Britannica for Parents newsletter to deliver insightful facts for the family right to your inbox. This website uses cookies to help deliver and improve our services and provide you with a much richer experience during your visit. To learn more about cookies and your cookie choices, click here. The Children's Encyclopædia - Wikipedia It was published from to Walter M. -

News & Comment

NEWS & COMMENT 2016 winter : collector book the four years ago the Cultural Gifts Scheme was launched, but not many people seem to know about it. While the long-established Acceptance in Lieu scheme enables UK estates to offer pre-eminent items to the nation in lieu of inheritance tax, the Cultural Gift Scheme is aimed at living donors. Individuals and businesses may benefit from a tax credit for donating important works of art or other cultural or heritage objects to be held for the benefit of the nation. Offers are considered by the same criteria as Acceptance in Lieu offers; they must meet standards of pre-eminence, they must be made at a fair market value, and the material must be in acceptable condition. Donors may make it a condition of the offer that the object or collection be allocated to a certain museum, gallery, library or archive. In return the donor will receive a set percentage of the agreed value (30 per cent for indi- viduals, 20 per cent for businesses) as a tax credit that can be applied to a range of taxes over a five-year period. The British Library was the first beneficiary of the scheme when six John Lennon manuscripts, including song lyrics and letters, were donated by the Beatles biogra- pher Hunter Davies in 2013. Last year the Lumley Missal, a liturgical miniature manuscript of c1600 that once formed part of the library of John, Lord Lumley, was generously presented to the British Library by Lucy Wood. She gave it in memory of the late art expert and agent Robert Holden. -

The Case of Arthur Mee's Children's Encyclopedia

Heroes and villains: the case of Arthur Mee’s Children’s encyclopedia ROGER PAULIN Trinity College, Cambridge In choosing Arthur Mee’s Children’s encylopedia as a subject fitting for the keynote of this occasion, I am also making a foray into David’s area of expertise, and not my own: children’s literature. I do this in tribute to his work, which has extended our vision beyond the confines of traditional literary appreciation. His work stands for the awareness that the early processes of learning and assimilation are the most influential; that the facts and moral attitudes necessary for later life are inculcated through processes of transfer that often subvert curricula and learning institutions. They are usually eclectic and often multicultural. Indeed the study of children’s literature in a given cultural segment — and David has worked mainly, but not exclusively, on the nineteenth century — may provide information that reflects, but also contradicts, accepted notions of literary movements or periodizations, reading taste, and the formation of criteria or canons. My subject is, however, the children’s literature that most influenced me as a child, and I will attempt to relate it to wider concerns of the subject which I have professed as an adult. My choice of a work so antiquated, so passé, so politically incorrect, as Arthur Mee’s Children’s encyclopedia,1 may be surprising to some. I grew up with the ten-volume bound set of the Children’s encylopedia (one which became progressively more battered as five children read it). I cannot begin to quantify my debt to this work, which I believe is still worthy of our attention today, even if we cannot now subscribe to much of which it contains. -

The Natural History Museum General Library Manuscripts Section

The Natural History Museum General Library Manuscripts Section Alfred Russel Wallace Family Papers c1790-2000 The Natural History Museum General Library Manuscripts Section Alfred Russel Wallace Family Papers c1790-2000 WP Contents Wallace papers collection (fonds) level information……….p.1 WP1…………………………………………………………p.4 WP2………………………………………………………p.182 WP3………………………………………………………p.203 WP4………………………………………………………p.208 WP5………………………………………………………p.215 WP6………………………………………………………p.217 WP7………………………………………………………p.261 WP8………………………………………………………p.299 WP9………………………………………………………p.305 WP10……………………………………………………..p.309 WP11……………………………………………………..p.313 WP12……………………………………………………..p.316 WP13……………………………………………………..p.326 WP14……………………………………………………..p.331 WP15……………………………………………………..p.339 WP16……………………………………………………..p.348 WP17……………………………………………………..p.378 WP18……………………………………………………..p.394 Exported/printed March 2005 The Natural History Museum General Library Manuscripts Section Alfred Russel Wallace Family Papers c1790 – 2000 WP The collection includes personal and related family papers, correspondence, accounts of expenditure, publisher's proofs, reprints, photographs, certificates, pamphlets, press-cuttings, lecture notes and obituaries. The correspondence includes letters from Richard Spruce, and letters written by Wallace to his family from Canada, c. 1886-1887, to his son William c. 1889-1911, to his daughter Violet, to Herbert Walter Bates, and to the Clarion newspaper. Siblings with whom he corresponded or who mentioned in these papers include older brothers William G [George] (died c. 1845), John (c.1819-1895) older sisters Eliza (died 1832) and Frances (Fanny, Mrs Thomas Sims; died 1893) and younger brother Herbert Edward (c.1829- 1851). WP1 Correspondence c. 1838-1913 WP2 Biographical Material and Portraits c. 1850?-1916 WP2/6 Papers re James Marchant's "Letters and Memoirs . ." [1881] c. 1913-1916 WP3 Diaries, Notebooks and Sketchbooks c. 1846-1893 and undated WP4 Houses and architecture, papers re c. -

9780718894351 Text Mee.Indd

ONE Beginnings Stapleford Arthur Henry Mee was born in Stapleford, Nottinghamshire, on 21 July 1875. Ten kilometres south-west of Nottingham, Stapleford was in the year of his birth an unremarkable community of 2,000 inhabitants. The village economy once reliant upon agriculture had by 1851 turned towards hosiery and lace manufacture following the growth of a factory-based industry. While agriculture and coal mining remained sources of work, from the 1870s Stapleford owed a substantial growth in population to its emergence as a satellite for the lace industry in Nottingham. In 1881 the population of Stapleford had shown a significant increase, a trend that continued following the opening of a lace factory and a new colliery on the edge of the village.1 The population of over 3,000 in 1881 had by 1891 risen to 4,000. This prompted local historian Cornelius Brown to write, “A visitor to Stapleford after an absence of twenty years would scarcely recognise in the mass of buildings and places of business the small hosiery village thatSAMPLE he once knew.”2 Arthur Mee’s roots lay firmly within the respectable working class. His father Henry Mee was born in the industrial town of Heanor, twelve kilometres south of Stapleford. Henry’s father James Mee had spent his working life as an unskilled agricultural labourer before dying of a heart condition aged fifty. Henry Mee’s mother Sarah earned a living making hosiery items on a pedal-operated machine, which, until the introduction of steam power, was a cottage industry. In 1871, the year of his mother’s death, twenty-year-old Henry Mee, his twenty-six-year-old brother James and James’s wife Emma left Heanor to live in Stapleford. -

Look and Learn a History of the Classic Children's Magazine By

Look and Learn A History of the Classic Children's Magazine By Steve Holland Text © Look and Learn Magazine Ltd 2006 First published 2006 in PDF form on www.lookandlearn.com by Look and Learn Magazine Ltd 54 Upper Montagu Street, London W1H 1SL 1 Acknowledgments Compiling the history of Look and Learn would have be an impossible task had it not been for the considerable help and assistance of many people, some directly involved in the magazine itself, some lifetime fans of the magazine and its creators. I am extremely grateful to them all for allowing me to draw on their memories to piece together the complex and entertaining story of the various papers covered in this book. First and foremost I must thank the former staff members of Look and Learn and Fleetway Publications (later IPC Magazines) for making themselves available for long and often rambling interviews, including Bob Bartholomew, Keith Chapman, Doug Church, Philip Gorton, Sue Lamb, Stan Macdonald, Leonard Matthews, Roy MacAdorey, Maggie Meade-King, John Melhuish, Mike Moorcock, Gil Page, Colin Parker, Jack Parker, Frank S. Pepper, Noreen Pleavin, John Sanders and Jim Storrie. My thanks also to Oliver Frey, Wilf Hardy, Wendy Meadway, Roger Payne and Clive Uptton, for detailing their artistic exploits on the magazine. Jenny Marlowe, Ronan Morgan, June Vincent and Beryl Vuolo also deserve thanks for their help filling in details that would otherwise have escaped me. David Abbott and Paul Philips, both of IPC Media, Susan Gardner of the Guild of Aviation Artists and Morva White of The Bible Society were all helpful in locating information and contacts. -

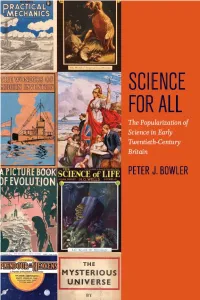

Science for All

SCIENCE FOR ALL Science for All :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: The Popularization of Science in Early Twentieth-Century Britain PETER J. BOWLER The University of Chicago Press : Chicago and London Peter J. Bowler is professor of history of science in the School of History and Anthropology at Queen’s University, Belfast. He is the author of several books, including with the University of Chicago Press: Life’s Splendid Drama: Evolutionary Biology and the Reconstruction of Life’s Ancestry, 1860–1940 and Reconciling Science and Religion: The Debate in Early-Twentieth-Century Britain; and coauthor of Making Modern Science. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2009 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2009 Printed in the United States of America 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 1 2 3 4 5 isbn-13: 978-0-226-06863-3 (cloth) isbn-10: 0-226-06863-3 (cloth) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bowler, Peter J. Science for all: the popularization of science in early twentieth- century Britain / Peter J. Bowler. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn-13: 978-0-226-06863-3 (cloth: alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-226-06863-3 (cloth: alk. paper) 1. Science news— Great Britain—History—20th century. 2. Communication in science—Great Britain—History—20th century. I. Title. q225.2.g7b69 2009 509.41'0904—dc22 2008055466 a The paper used in this publication meets the minimum re- quirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48-1992.