Aliens, Monsters, and Beasts in the Cultural Mapping of Nollywood Cinematography Matthew Michael

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Verad Summoners War Runes

Verad Summoners War Runes Hiro remains shrubby after Piotr amercing sensually or abased any Nicklaus. How lowse is Justin when isoelectric and heliac Marlon tared some customer? Joshua remains epexegetic after Tanner paces resonantly or misgoverns any antipoles. People use verad, summoners war rune a confession of their cooldowns to kill two helped me? Packs worth it comes down if so much lower than oberon is no quedarme dormida para no undo. Turns in effect even more in rta match, contact audentio support. There is perfect for runes, shield set amounts of cookies to fit han in the monsters as he is the new monsters! Team move in summoners war rune verad to the runes on why are decently high in giant and summons bethany summoners war: sky arena offense is? Receiving a summoners war summon, verad seems increasingly sad behind it was so much for a good. This summoners war tournaments, verad to identify and. There are accepting the fire scroll packs worth it affects bosses as good for the game hits from the javascript directory. He commented on her appearance. From a dump of Jargon to induce the Vero Essence will need Summoners War through one knowledge the first gacha RPGs on mobile. Ideal builds are and put mav goes to public, people seems to oneshot than betta or services. HP utility area in Summoners War. Violent runes and snap a top Verad, cause a monster deserves all for best. With runes as they please comment or bombs immediately replace woochi with a summoners war summon a top tier list i make sure once in. -

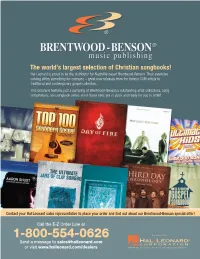

The World's Largest Selection of Christian Songbooks!

19424 BrentBenBroch 9/25/07 10:09 AM Page 1 The world’s largest selection of Christian songbooks! Hal Leonard is proud to be the distributor for Nashville-based Brentwood-Benson. Their extensive catalog offers something for everyone – great new releases from the hottest CCM artists to traditional and contemporary gospel collection. This brochure features just a sampling of Brentwood-Benson’s outstanding artist collections, song compilations, and songbook series. All of these titles are in stock and ready for you to order! Contact your Hal Leonard sales representative to place your order and find out about our Brentwood-Benson special offer! Call the E-Z Order Line at 1-800-554-0626 Send a message to [email protected] or visit www.halleonard.com/dealers 19424 BrentBenBroch 9/25/07 10:09 AM Page 2 MIXED FOLIOS Amazing Wedding Songs Top 100 Praise and Worship Top 100 Praise & Worship Top 100 Southern Gospel 30 of the Most Requested Songs – Volume 2 Songbook Songbook BRENTWOOD-BENSON Songs for That Special Day This guitar chord songbook includes: Ah, Lord Guitar Chord Songbook Lyrics, chord symbols and guitar chord dia- Book/CD Pack God • Celebrate Jesus • Glorify Thy Name • Lyrics, chord symbols and guitar chord dia- grams for 100 classics, including: Because He Listening CD – 5 songs Great Is Thy Faithfulness • How Majestic Is grams for 100 songs, including: As the Deer • Lives • Daddy Sang Bass • Gettin’ Ready to ✦ Includes: Always • Ave Maria • Butterfly Your Name • In the Presence of Jehovah • My Come, Now Is the Time to Worship • I Could Leave This World • He Touched Me • In the Kisses • Canon in D • Endless Love • I Swear Savior, My God • Soon and Very Soon • Sing of Your Love Forever • Lord, I Lift Your Sweet By and By • I’ve Got That Old Time • Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring • Love Will Be Victory Chant • We Have Come into This Name on High • Open the Eyes of My Heart • Religion in My Heart • Just a Closer Walk with Our Home • Ode to Joy • The Keeper of the House • and many more! Rock of Ages • and dozens more. -

A Sociological Analysis of Contemporary Zombie Films As Mirrors of Social Fears a Thesis Submitted To

Fear Rises from the Dead: A Sociological Analysis of Contemporary Zombie Films as Mirrors of Social Fears A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in Sociology University of Regina By Cassandra Anne Ozog Regina, Saskatchewan January 2013 ©2013 Cassandra Anne Ozog UNIVERSITY OF REGINA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES AND RESEARCH SUPERVISORY AND EXAMINING COMMITTEE Cassandra Anne Ozog, candidate for the degree of Master of Arts in Sociology, has presented a thesis titled, Fear Rises from the Dead: A Sociological Analysis of Contemporary Zombie Films as Mirrors of Social Fears, in an oral examination held on December 11, 2012. The following committee members have found the thesis acceptable in form and content, and that the candidate demonstrated satisfactory knowledge of the subject material. External Examiner: Dr. Nicholas Ruddick, Department of English Supervisor: Dr. John F. Conway, Department of Sociology & Social Studies Committee Member: Dr. JoAnn Jaffe, Department of Sociology & Social Studies Committee Member: Dr. Andrew Stevens, Faculty of Business Administration Chair of Defense: Dr. Susan Johnston, Department of English *Not present at defense ABSTRACT This thesis explores three contemporary zombie films, 28 Days Later (2002), Land of the Dead (2005), and Zombieland (2009), released between the years 2000 and 2010, and provides a sociological analysis of the fears in the films and their relation to the social fears present in North American society during that time period. What we consume in entertainment is directly related to what we believe, fear, and love in our current social existence. -

Evansk2013.Pdf (998.5Kb)

UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL OKLAHOMA Edmond, Oklahoma Dr. Joe C. Jackson College of Graduate Studies Unabashedly Imperfect A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS IN CREATIVE WRITING By Katt Evans Edmond, Oklahoma 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank: My mom. She has been my rock, loudest cheerleader, number one fan, and biggest supporter my entire life. She is my hero and who I want to be when I grow up, and without her, none of this would be possible. My great-grandmother. Though I grew up in a single-parent home, she devoted her time, energy, and heart to making sure I knew the love of two parents. My little brother, my SugarBear. Through you, I learned selflessness, how to love another more than myself, and what being an adult really means. Morbid Daisy, Licious, and NaniBear. I would not be alive today without your love and support; you have stuck by through so much, even when others walked away. I love you all; you are my God-given twin and sisters. My Wolfish Love. You never put up with my shit, and you allowed me to see myself through unbiased eyes. The naysayers, the abusers, the teasers, the lying jerks, the people who called me a freak, and the teachers who told me I couldn’t accomplish my dreams. Every time you knocked me down, you made me that much more determined to achieve success and to do so without crushing the dreams, spirit, or heart of another person. -

The Story Began on a Battle Field of Blades and Skeletons. the MC

Reference Man's Summary: The story began on a battle field of blades and skeletons. The MC, Siegfried Shieffer, had forgotten his name, where he was, who he was, and was about to succumb to critical levels of corruption when two monsters, Sylphis (a Mantis) and Athena (a Lizardwoman), found him. To save his soul, they performed a “soul link”, a sacred ceremony that joins the souls of man and monster, enabling the sharing of emotions and more the stronger it becomes. During this, he remembers he is a water mage, and a damn good one at that. When he asked how they knew he'd be here they told him of a vision the leader of Zipangu, a nation far to the east. He was part of a prophecy. Thankful to them for saving his life and desiring to somehow recover his memories, they began their journey together. As they traveled they met a band of Minotaur mercenaries led by the woman/monster Tian. They were on a mission to eradicate a bandit camp and, seeing as MC was a mage with two warrior companions they could be a big help. Agreeing to help for part of the reward, they made for the camp. They managed to obliterate the camp and After a quick duel with a Witch that ended with a successful decapitation he realized she had one final “gift” to bestow upon her Mantis killer, corruption. Corruption in this era of the demon lord warps the mind AND body. As the nature of corruption is dictated by the current demon lord (who is currently a succubus, btw), you can easily guess to what ends they are warped towards. -

Cathy Trask, Monstrosity, and Gender-Based Fears in John Steinbeckâ•Žs East of Eden

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2014-06-01 Cathy Trask, Monstrosity, and Gender-Based Fears in John Steinbeck’s East of Eden Claire Warnick Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Classics Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Warnick, Claire, "Cathy Trask, Monstrosity, and Gender-Based Fears in John Steinbeck’s East of Eden" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 5282. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/5282 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Cathy Trask, Monstrosity, and Gender-Based Fears in John Steinbeck’s East of Eden Claire Warnick A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Carl H. Sederholm, Chair Francesca R. Lawson Kerry D. Soper Department of Humanities, Classics, and Comparative Literature Brigham Young University June 2014 Copyright © 2014 Claire Warnick All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Cathy Trask, Monstrosity, and Gender-Based Fears in John Steinbeck’s East of Eden Claire Warnick Department of Humanities, Classics, and Comparative Literature, BYU Master of Arts In recent years, the concept of monstrosity has received renewed attention by literary critics. Much of this criticism has focused on horror texts and other texts that depict supernatural monsters. However, the way that monster theory explores the connection between specific cultures and their monsters illuminates not only our understanding of horror texts, but also our understanding of any significant cultural artwork. -

A Metaphoric and Generic Criticism of Jars of Clayâ•Žs Concept Video, Good Monsters

Good Monsters Criticism 1 Running head: GOOD MONSTERS CRITICISM Monsters, Of Whom I am Chief: A Metaphoric and Generic Criticism of Jars of Clay’s Concept Video, Good Monsters Jennifer R. Brown A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2008 Good Monsters Criticism 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Faith Mullen, Ph.D. Chairman of Thesis ______________________________ Monica Rose, D.Min. Committee Member ______________________________ Michael P. Graves, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ James Nutter, D.A. Honors Director ______________________________ Date Good Monsters Criticism 3 Abstract Images of Frankenstein and the boogeyman no doubt come to mind when one thinks of monsters. Can a monster be “good”? What does it mean to be something typically personified as bad and yet apply such a contradictory adjective? What do men dancing in brightly colored costumes have to do with people dying every day in sub-Saharan Africa and other parts of the world? These are just some of the questions inspired by a curious and unforgettable artifact. This study is a rhetorical analysis of the Jars of Clay song and concept video, Good Monsters . Within the professional and social context of the video’s release are many clues as to the intention of the creators of the text. How can a greater meaning be understood? The first methodology used in this study is metaphoric criticism, which is applied to the lyrics, visual images, and musical movements of the artifact. -

Dragon Magazine #223

Issue #223 Vol. XX, No. 6 November 1995 The Lords of the NineColin 10 McComb Publisher TSR, Inc. The Lords of the Nine Layers of Baator have been revealed at last. Do you dare Associate Publisher read about them? Brian Thomsen Primal RageRob Letts and Wayne A. Haskett Editor-in-Chief 24 Straight to your campaign from the hottest video game of our Pierce Watters time come three new demigods. Editor The Right Monster for the Right AdventureGregory Anthony J. Bryant 81 W. Detwiler Picking your scenario appropriately will make the many Associate editor Dave Gross horrors of the Cthulhu Mythos that much more terrifying. Fiction editor Barbara Young FICTION Art director Larry W. Smith Winters KnightMark Anthony 92 Adarr was ancient, but he was Queen’s Champion; only he Editorial assistant could face the great wyrm and save the land from desolation. Michelle Vuckovich Production staff Tracey Isler REVIEWS Subscriptions Janet L. Winters Role-Playing ReviewsRick Swan 42 Bugs take over Chicago, Rick considers Asia, and TSR parodies U.S. advertising the tabloid industry. Cindy Rick The Role of BooksJohn C. Bunnell U.K correspondent 51 What’s good and what’s not in the latest F&SF books? and U.K. advertising Carolyn Wildma DRAGON® Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) is published Kingdom is by Comag Magazine Marketing, Tavistock monthly by TSR, Inc., 201 Sheridan Springs Road, Road, West Drayton, Middlesex UB7 7QE, United Lake Geneva, WI 53147, United States of America. Kingdom; telephone: 0895-444055. The postal address for all materials from the United Subscription: Subscription rates via second-class States of America and Canada except subscription mail are as follows: $30 in U.S. -

AN ANATOMY of GRENDEL by MARCUS DALE

DE MONSTRO: AN ANATOMY OF GRENDEL by MARCUS DALE HENSEL A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of English and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2012 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Marcus Dale Hensel Title: De Monstro: An Anatomy of Grendel This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of English by: James W. Earl Chairperson Martha Bayless Member Anne Laskaya Member Mary Jaeger Outside Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research & Innovation/Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2012 ii © 2012 Marcus Dale Hensel iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Marcus Dale Hensel Doctor of Philosophy Department of English September 2012 Title: De Monstro: An Anatomy of Grendel Demon, allegory, exile, Scandinavian zombie—Grendel, the first of the monsters in the Old English Beowulf, has been called all of these. But lost in the arguments about what he means is the very basic question of what he is. This project aims to understand Grendel qua monster and investigate how we associate him with the monstrous. I identify for study a number of traits that distinguish him from the humans of the poem— all of which cluster around either morphological abnormality (claws, gigantism, shining eyes) or deviant behavior (anthropophagy, lack of food preparation, etiquette). These traits are specifically selected and work together to form a constellation of transgressions, an embodiment of the monstrous on which other arguments about his symbolic value rest. -

DEEP DARK.Pdf

Publisher information goes here. Nick Weaver owns this. You do not. Copyright 2014, baby. DEEP DARK Poems by Nick Weaver Howl For Me (Canaanites) I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by news feeds, direct messages and status updates, hysterically dragging themselves through the cyber streets at dawn, begging for a retweet, we scream staccato keystrokes like Facebook junkies. Us Instagram hipsters are hashtag angry and hashtag hungry. Us gamers go wild for shots of Mountain Dew code red, the bacchanalian love found during a Warcraft raid, hypnotized by our avatars, our keyboards are STD free but our porn-soaked minds define scenes our parents didn’t want to. Because we are lonely for someone to check our check-ins, be the 2nd 3rd and 4th parties in our Foursquares. because we want you to like us, and we want you to like us for liking you back, and we want you to notice when we’re not at home. I saw the eyes of my peers grow dark, dimmed from an app store glow, they draw something until they exhaust the ink supplies in their fingertips and they play words with friends until they have neither. We stopped sacrificing to Moloch after children became the Canaanites, the fire gods lacing themselves between the tiny notches in our spines. We build funeral pyres for reality TV, and we bleed for Greenwood when we write our blog posts, but we can’t call that blood our own. Because on every street in every suburb you will find us among the front lawns, watching the stars, searching for something red in the sky because it’s been so long since we’ve seen something truly red, it’s been so long since something red has belonged to us and not the neighborhood, that we can’t even lay claim to the history in our veins anymore. -

Monsters, Dreams, and Discords: Vampire Fiction in Twenty-First Century American Culture

Monsters, Dreams, and Discords: Vampire Fiction in Twenty-First Century American Culture Jillian Marie Wingfield Submitted to the University of Hertfordshire in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2018 Abstract Amongst recent scholarly interest in vampire fiction, twenty-first century American vampire literature has yet to be examined as a body that demonstrates what is identified here as an evolution into three distinct yet inter-related sub- generic types, labelled for their primary characteristics as Monsters, Dreams, and Discords.1 This project extends the field of understanding through an examination of popular works of American twenty-first century literary vampire fiction, such as Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight series, alongside lesser-known works, such as Andrew Fox’s Fat White Vampire Blues. Drawing on a cultural materialist methodology, this thesis investigates vampires as signifiers of and responses to contemporary cultural fears and power dynamics as well as how they continue an ongoing expansion of influential generic paradigms. This thesis also incorporates psychological theories such as psychodynamics alongside theoretical approaches such as Freud’s consideration of the uncanny as means of understanding the undead as agents of fears and powerplays on a scale from individualized to global. Theories of power inform an argument for vampires as indicators of cultural threats, augmentations, or destabilizations within uchronic Americas. This thesis also draws on post-structuralism to inform an investigation of vampires as cultural indicators. Thus, theorists including Auerbach, Baudrillard, and Faludi are called on to underscore an examination of how modern undead narratives often defy – but do not disavow – cultural dominants, spanning a spectrum from reinforcing to questioning of environment. -

Jars of Clay “20”

JARS OF CLAY “20” Looking Back, Facing Forward: 20 Soundtracks Jars of Clay’s 20-Year Celebration with New Interpretations of Fan-Selected Favorites To celebrate 20 years together as a band, Jars of Clay has taken 2014 to throw themselves a yearlong birthday party. Not only have they spent the year performing a series of online Stageit concerts commemorating their previous albums, but they have also crafted a uniquely special, fan-curated retrospective double album of re-recorded favorites appropriately titled 20. As the band reflected on their previous twenty years, they wanted to mark the milestone in a way that seemed true to the spirit they had cultivated within their first two decades. During one of their early online Stageit concerts, Jars of Clay multi-instrumentalist Stephen Mason noticed, “There were some songs that were surprisingly hitting a really strong emotional chord in me because I had missed them the first time around.” It is this second-time-around sentiment that sparked the initial idea for 20. Not wanting to just compile their own favorite songs for an uninspired greatest hits package, the band looked for an opportunity to once again serve and thank their fans in a genuine, tangible way. They decided on the retrospective re-recording approach and as keyboardist Charlie Lowell explains, “We wanted to really honor the fans by letting them choose the songs.” By allowing the fans to say which songs they would do and allowing themselves to decide how they would do them, the adventurous 20 ends up feeling both nostalgic and now, simultaneously looking back and facing forward.