Synchrony Financial Petition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PREPAID CARD by MAIL with Any Purchase of $750 Or More Made with the Synchrony Bank Music Credit Card.1

GET A $ PREPAID CARD BY MAIL with any purchase of $750 or more made with the Synchrony Bank Music credit card.1 Offer valid December 1 – December 31, 2017. Rebate form must be postmarked by January 31, 2018. Step 1: Make a single-receipt purchase with your Synchrony Bank Music credit card. Step 2: Complete this form, including mailing information and last 4 digits of the Synchrony credit card used. Name __________________________________________________________________________________________ Address ____________________________________________________________________________________ Last 4 digits of Synchrony credit card _________________________________________ City __________________________________________________________________________________________ Invoice # _____________________________________________________________________________________ State _______________________ Zip _______________________________________________________ Phone __________________________________________________________________________________________ Email (optional) _________________________________________________________________________ Step 3: Send a copy of your receipt, along with this completed form, to the address below. Music Credit Rebate Offer #5604 P.O. Box 7210 Mesa, AZ 85216 Please keep a copy of this rebate form and your original invoice for your records. Visit myrebatemanager.com or call 1-855-333-2820 to inquire about status. 1To be eligible to receive a rebate under this offer you must: (1) make a purchase of $750 or more on a single receipt from 12/01/2017 – 12/31/2017 with your Synchrony Bank Music credit card; (2) complete and submit a rebate form, together with a copy of the original receipt, that is postmarked by 1/31/2018. Cardholders who use their Synchrony Bank Music credit card for their qualifying purchase will be eligible to receive a $100 Visa Prepaid Card. Purchases with a Synchrony Bank Music credit card are subject to credit approval. One rebate per qualifying purchase valid at participating U.S. locations. See store for details. -

Synchrony: a Growing Credit-Card Powerhouse As It Outpaces Its Competitors, the Private-Label Giant Is Poised to See Its Shares Spike Later This Year

WSJ WSJ LIVE MARKETWATCH BARRON'S PORTFOLIO DJX MORE News, Quotes, Companies, Videos SEARCH ASIA EDITION U.S. EDITION Log In Subscribe HOME MAGAZINE DAILY INVESTING IDEAS TOP ADVISORS MARKET DATA PAID ADVISOR DIRECTORY FEATURE Synchrony: A Growing Credit-Card Powerhouse As it outpaces its competitors, the private-label giant is poised to see its shares spike later this year. Email Print 3 Comments Order Reprints By LAWRENCE C. STRAUSS February 20, 2016 Synchrony partners with 22 major retailers, including the names below, to issue private-label cards. The credit-card industry is facing head winds as major players duke it out for customers. But one part of the market isn’t getting enough credit: private-label cards, which typically are branded with one retailer and offer consumers perks that include discounts, loyalty rewards, and promotional financing. Private cards are gaining market share, growing at a 7% annual clip, compared with 5% for traditional offerings, says Bill Carcache, an analyst at Nomura Securities. The industry leader is Synchrony Financial (ticker: SYF), which was spun off from General Electric (GE) in 2014. The company has gained 12 points of market share since 2004, to an estimated 43%, according to the Nilson Report and Nomura, and its loan portfolio should grow by some 8% this year, thanks to continued market-share gains and a healthy U.S. consumer. Synchrony’s retail-card division partners with 22 merchants, including Amazon.com (AMZN) and Chevron (CVX). Synchrony “sits in the sweet spot of the [retail] payments Most Popular ecosystem, where we expect it will continue to outperform,” Carcache noted after it What Recession? GDP Set to Grow 3% announced solid fourth-quarter results on Jan. -

Growth of Financial Service Sector in India

IOSR Journal of Business and Management (IOSR-JBM) e-ISSN: 2278-487X, p-ISSN: 2319-7668 PP 24-26 www.iosrjournals.org Growth of Financial Service Sector in India Nivedhita.J Ph.D., (Part time) Research Scholar in Management, P.K.R Arts College for Women, Gobichettipalayam. I. Introduction India has a diversified financial sector undergoing rapid expansion, both in terms of strong growth of existing financial services firms and new entities entering the market. The sector comprises commercial banks, insurance companies, non-banking financial companies, co-operatives, pension funds, mutual funds and other smaller financial entities. The banking regulator has allowed new entities such as payments banks to be created recently thereby adding to the types of entities operating in the sector. However, the financial sector in India is predominantly a banking sector with commercial banks accounting for more than 64 per cent of the total assets held by the financial system. The Government of India has introduced several reforms to liberalise, regulate and enhance this industry. The Government and Reserve Bank of India (RBI) have taken various measures to facilitate easy access to finance for Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs). These measures include launching Credit Guarantee Fund Scheme for Micro and Small Enterprises, issuing guideline to banks regarding collateral requirements and setting up a Micro Units Development and Refinance Agency (MUDRA). With a combined push by both government and private sector, India is undoubtedly one of the world's most vibrant capital markets. II. Market Size Total outstanding credit by scheduled commercial banks of India stood at Rs 72,606.11 billion (US$ 1.08 trillion)!. -

Proposed Community Reinvestment Act Strategic Plan of American

Community Reinvestment Act Strategic Plan of American Challenger Bank, N.A. (proposed) Stamford, Connecticut November 10, 2020 CRA STRATEGIC PLAN Table of Contents SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1 A. General Information .......................................................................................................................... 1 B. Bank’s Specialized Business Model ................................................................................................. 1 C. Financial Information ........................................................................................................................ 3 SECTION 2: COMMUNITY REINVESTMENT ACT ............................................................................... 4 A. CRA Requirements ........................................................................................................................... 4 B. Strategic Plan - Overall Focus, Effective Date, and Term ................................................................ 6 C. Bank’s Commitment to CRA ............................................................................................................ 6 D. Program Oversight and Resources .................................................................................................... 7 E. Development of Bank’s CRA Strategic Plan .................................................................................... 7 SECTION 3: BANK’S ASSESSMENT -

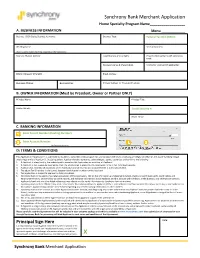

Synchrony Bank Merchant Application Home Specialty Program Name______A

Synchrony Bank Merchant Application Home Specialty Program Name__________________ A. BUSINESS INFORMATION Menu ____________ Business / DBA (Doing Business As) Name: Business Type: Federal Tax ID # (EIN #): IRS Filing Name: Years in Business: {Name used for federal tax filing; required per IRS Regulations) Business Physical Address: Total Business Annual Sales: Projected Annual Sales with Synchrony Bank: Business License # (if applicable): Contractor License # (if applicable): Billing Address (if different): Email Address: Business Phone: Business Fax: Primary Contact for Financing Program: B. OWNER INFORMATION (Must be President, Owner or Partner ONLY) Principal Name: Principal Title: Home Address: Social Security #: Home Phone: C. BANKING INFORMATION Bank Transit Number (Routing Number): Bank Account Number: No Personal Accounts D: TERMS & CONDITIONS This Application (“Application”) is submitted to establish a consumer credit program for, and to obtain merchant processing privileges on behalf of, the above-named principal and/or legal entity (“Applicant”). By signing below, Applicant hereby represents, acknowledges, agrees, authorizes and confirms the following: 1. If Applicant is a legal entity, the undersigned is executing this Application as an officer of Applicant. 2. If Applicant is not a separate legal entity, then the undersigned is executing this Application in his or her individual capacity. 3. Applicant has reviewed all provisions of this Application and all information provided herein is true and complete. 4. The above Tax ID number is the correct taxpayer identification number for the Applicant. 5. This application is subject to approval by Synchrony Bank. 6. Synchrony Bank or its agents, may retain possession of this Application, rely on the information and statements herein, check and verify Applicant’s credit history and employment history, secure follow up credit reports, and exchange information about Applicant and this account with creditors, credit bureaus, and other proper persons. -

To SBI Cards and Payment Services Ltd. Niche Product in the Consumer Oriented Business 27Th Feb

“SUBSCRIBE” to SBI Cards and Payment Services Ltd. Niche product in the consumer oriented business 27th Feb. 2020 Salient features of the IPO: Recommendation SUBSCRIBE • SBI Cards and Payment Services Ltd. (SBI Card), another PSU stock is Price Band Rs. 750 - 755 per Share about to enter equity market with its IPO, which opens on 2nd Mar. and close on 5th Mar. 2020. The price band is Rs. 750 - 755 per share. Face Value Rs. 10 • The issue comprises of 137.15 - 137.19mn shares (fresh issue: 6.62 - Shares for Fresh Issue 6.62 - 6.67mn Shares 6.67; OFS shares: 130.53mn shares) in offering. Total IPO size is Rs. Shares for OFS 130.53mn Shares 102,895.1 - 103,547.7mn. Fresh Issue Size Rs. 5,000mn • The company will not receive any proceeds from OFS. Majority of the OFS Issue Size Rs. 97,895.1 - 98,547.7mn fresh issue net proceeds, will be utilize by the company to augment 137.15 - 137.19mn Shares Total Issue Size the capital base so as to meet the future capital requirement. (Rs. 102,895.1 - 103,547.7mn) 02nd Mar. - 05th Mar. 2020 Key competitive strengths: Bidding Date (For QIB bidder, offer closes on • Second largest credit card issuer in India with deep industry expertise 04th Mar. 2020) and a demonstrated track record of growth and profitability Reserved for SBI Cards • Diversified customer acquisition capabilities 1.86mn Shares • Supported by a strong brand and pre-eminent promoter Employees (mn Shares) Reserved for SBI • Diversified portfolio of credit card offerings 13.05mn Shares • Advanced risk management and data analytics capabilities Shareholders (mn Shares) • Modern and scalable technology infrastructure Net Offer for Sales (mn 122.23 - 122.28mn Shares • Highly experienced and professional management team Shares) (Rs. -

Global Affinity AFFINITY BANKING Finance Club

AFFINITY INSURANCE QUARTER 3 2018 BANCASSURANCE Global Affinity AFFINITY BANKING Finance Club Finaccord’s newsletter about affinity financial services worldwide Welcome back to your Club! As has been the case in recent quarters, affinity and partnership mar- keting deals with a strong digital slant are especially prominent in this latest round-up. Examples include Onlia (a personal lines insurance joint venture set up by Achmea and Fairfax Financial in Canada), the tie of Friendsur- ance with Ottonova (for digital health insurance in Germany), and the mandate acquired by Urgent.ly with Uber in the US for on- demand, app-based road assistance (complementing the launch of a co-branded debit card for Uber drivers issued by GoBank). Another notable initiative is an online platform for vehicle owners in China (incorporating motor insurance, vehicle finance and other related services) established by two giants of the country’s financial services sector, namely ICBC and PICC. In a similar vein, Allianz and Deutsche Bank are working in Germany with Auto1, an online marketplace that matches individuals wishing to sell used cars to dealerships, to launch a new venture called Auto1 Fintech. Again, this has a focus on insurance and finance products but this time with the vehicle dealerships as the target customers. Elsewhere, China-based payment brand UnionPay continues to take steps to establish itself at an international level. Its latest ventures include the launch of a co-branded credit card with Ctrip and Sumi- tomo Mitsui in Japan plus various other initiatives to boost issuance and acceptance of its cards in geographies as diverse as Belarus, Can- ada, France, Panama, Serbia, Spain, Uganda and Ukraine. -

Synchrony Financial

SYNCHRONY FINANCIAL Basel III Pillar 3 Regulatory Capital Disclosure Report September 30, 2020 Synchrony Financial Table of Contents Page Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Capital Structure .................................................................................................................................................... 5 Capital Adequacy ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Capital Conservation Buffer ................................................................................................................................... 9 Credit Risk: General Disclosures ........................................................................................................................... 10 Credit Risk Mitigation ............................................................................................................................................. 14 Securitizations ....................................................................................................................................................... 14 Equities Not Subject to Market Risk Rule .............................................................................................................. 15 Interest Rate Risk for Non-Trading Activities ......................................................................................................... -

Web Fraud Prevention, Identity Verification & Authentication Guide 2018 -2019

Web Fraud Prevention, Identity Verification & Authentication Guide 2018 -2019 LATEST INSIGHTS INTO DIGITAL ONBOARDING AND FRAUD MITIGATION FOR BANKS, MERCHANTS AND PSPS Key Media Partners Endorsement Partners Web Fraud Prevention, Identity Verification & Authentication Guide 2018 -2019 LATEST INSIGHTS INTO DIGITAL ONBOARDING AND FRAUD MITIGATION FOR BANKS, MERCHANTS AND PSPS Contact us For inquiries on editorial opportunities please contact: Email: [email protected] To subscribe to our newsletters, click here For general advertising information, contact: Mihaela Mihaila Email: [email protected] RELEASE VERSION 1.0 DECEMBER 2018 COPYRIGHT © THE PAYPERS BV ALL RIGHTS RESERVED TEL: +31 20 893 4315 FAX: +31 20 658 0671 MAIL: [email protected] Editor’s letter Customer experience and the conflict between offering a fric However, fraud attacks are becoming more sophisticated, with tionless customer service to good clients while managing risk fraudsters having access to the latest technology and sophis ti cated and blocking the bad guys are some themes that are emerging tools. Therefore, what is really needed? A fraud management from acquirers, card schemes, regulators, service providers, solution can track the customer’s behavioural patterns (beha- merchants, as well as auditors and journalists alike. vioural profiling) and instantly detect and report any signs of fraud, triggering a step up authentication to mitigate the Identifying fraudulent behaviour without rejecting or offending potential risk (risk-based authentication). good customers is key because a blocked good customer will not return, and as the market is so competitive, they can go every- Similarly, when it comes to financial institutions (FIs), FIs where. Moreover, automation technologies based on machine are under intense competitive pressure to make the banking learning and artificial intelligence are gaining prominence in this experience easier and frictionless (while regulators in Europe conversation. -

Top 150 Merchant Acquirers Worldwide Companies from 45 Countries Generated 342.2 Billion Purchase Transactions

ISSUE 1183 SEPTEMBER 2020 ARTICLES IN THIS ISSUE p5 Top 150 Merchant Acquirers p12 Acquiring-as-a-Service Worldwide Platform from FSS p7 Top 100 U.S. Mastercard and p13 Point of Sale Terminal Visa Issuers at Midyear Manufacturers — Part 2 p10 Buy Now, Pay Later Funding p14 Top General Purpose Deals in 2020 Credit Card Issuers in the United States at Midyear p11 PayNearMe Payment Processing TRANSACTIONS (BIL.) IN 2019 Top 150 Merchant Acquirers Worldwide Companies from 45 countries generated 342.2 billion purchase transactions. The six companies listed below accounted for 41% or 141.8 billion of those transactions. Read full article on page 5 FIS (WORLDPAY) 36.72 JPMORGAN CHASE 29.41 SBERBANK 20.61 FISERV 20.36 (FIRST DATA) BANK OF 18.56 AMERICA 16.19 GLOBAL PAYMENTS FOR 50 YEARS, THE LEADING PUBLICATION COVERING PAYMENT SYSTEMS WORLDWIDE CONTENTS COVER STORY Top 150 Merchant Acquirers Outstandings for the top 10 Worldwide Acquirers headquartered in 45 countries included 32 in the U.S. issuers of Mastercard and U.S., 10 in Turkey, 7 in France, Russia, and Iran, and 5 in Brazil Visa credit cards totaled and Japan. p5 $569 bil. as of June 30, 2020, down 9.8% from June 30, 2019 Top 100 U.S. Issuers of Visa and Mastercard Credit Cards at Midyear Rankings are based on outstandings as of June 30, 2020 and on purchase volume for January 1 through June 30, 2020. Acquiring-as-a-Service Platform p7 from FSS Embark is a cloud-based managed service accessed through a single connection and integration. -

Synchrony Financial Rates and Fees Table Ebay Extras

FR833282333_EBAY MASTERCARD T&C DC PDF 21216FF, 21216GG 09/16 SYNCHRONY FINANCIAL RATES AND FEES TABLE EBAY EXTRAS MASTERCARD® ACCOUNT AGREEMENT PRICING INFORMATION Interest Rates and Interest Charges Annual Percentage The APR for purchases is the prime rate plus (i) 16.74% for Account Type 1 or (ii) 20.74% for Account Type 2. Rate (APR) for Rates are determined when you open your account, based on creditworthiness and other factors. Purchases These rates will vary with the market based on the Prime Rate. APR for Cash The APR for cash advances is the prime rate plus 23.74% Advances This APR will vary with the market based on the Prime Rate. Paying Interest Your due date is at least 23 days after the close of each billing cycle. We will not charge you any interest on purchases if you pay your entire balance by the due date each month. We will begin charging interest on cash advances on the transaction date. Minimum Interest If you are charged interest, the charge will be no less than $1.50. Charge Fees Transaction Fees • Cash Advance Either $5 or 3% of the amount of each cash advance, whichever is greater. • Foreign 3% of each transaction. Transaction Penalty Fees • Late Payment Up to $37 How We Will Calculate Your Balance: We use a method called “daily balance”. See your credit card account agreement that follows for more details. 1 SECTION II: RATES, FEES AND PAYMENT INFORMATION EBAY EXTRAS MASTERCARD® ACCOUNT AGREEMENT How Interest is Calculated Your Interest We use a daily rate to calculate the interest on the balance on your account each day. -

Payments 2016 / the Year Of

Payments 2016 / The Year Of... 21 Executive Responses DECEMBER 2016 Welcome! to the “Payments 2016, The Year Of…” eBook! From open APIs to omnichannel, EMV chip In the following pages of the “Payments 2016, cards to faster payments, it’s hard to put a The Year Of…” eBook, thought leaders in the finger on exactly which happenings in the industry not only provide an in-depth look into payments space had the biggest impact in some of the biggest impacts to payments this 2016. There were many shifts and trends in the year but also deliver a glimpse into what the ecosystem this year, some that will surely have future may hold in the ever-evolving world of an impact on how payments stakeholders commerce. Believe us, how they responded operate for years to come. may just surprise you! But picking the most influential is a tough job. We hope you enjoy the eBook! Lucky for us, we’ll let the industry speak for itself on this one. Cheers to 2017! PYMNTS consulted 21 payments executives from across the industry to share their insights on the biggest takeaways from 2016. We posed the same question to each executive… If you had to answer the question: Payments was the year of… how would you answer, and how does your answer change your world — and the world of payments more broadly? © 2016 PYMNTS.com all rights reserved 2 Table of Contents Payments 2016, The Year Of… ACI Worldwide, CTP, Head of Digital Banking Channels, Mark Ranta 4 AOC Solutions, Chief Technology Officer, Dan Seewer 5 Applause, Senior VP, Rahul Shah 7 CA Technologies, Director, Payment