SRC 12 Interviewer: Susan Glisson Interviewee: Julius Chambers Date: August 6, 2002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Interview with Ambassador Andrew Young

Nonprofit Policy Forum Volume 1, Issue 1 2010 Article 7 An Interview with Ambassador Andrew Young Dennis R. Young, Georgia State University Recommended Citation: Young, Dennis R. (2010) "An Interview with Ambassador Andrew Young," Nonprofit Policy Forum: Vol. 1: Iss. 1, Article 7. DOI: 10.2202/2154-3348.1009 An Interview with Ambassador Andrew Young Dennis R. Young Abstract Ambassador Andrew Young talks about the major policy issues of the day and how nonprofits can be more effective in the policy process and in addressing social needs. KEYWORDS: interview, public policy, religion, international Young: An Interview with Ambassador Andrew Young Andrew J. Young is Chairman of GoodWorks International, a former chairman of the Southern Africa Enterprise Development Fund, an ordained minister, international businessman, human rights activist, author and former U.S. representative, Ambassador to the United Nations and Mayor of the City of Atlanta. He also served as president of the National Council of Churches and was a supporter and friend of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Among his numerous achievements he was instrumental in bringing the Olympic Games to Atlanta in 1996. He was interviewed in his office on June 14, 2010 on the subject of nonprofits and public policy by Prof. Dennis R. Young (no relation), Chief Editor of Nonprofit Policy Forum and Director of the Nonprofit Studies Program in the Andrew Young School of Policy Studies at Georgia State University. DY: You have had a distinguished career in government, business and the nonprofit sector. In your view, how effective are nonprofits in helping to shape good public policy? Where do they fall short? How can they be more effective? AY: I sometimes quote Dr. -

The Powerbroker: Whitney Young’S Fight for Civil Rights

DISCUSSION GUIDE The Powerbroker: Whitney Young’s Fight for Civil Rights PBS.ORG/indePendenTLens/POWERBROKER Table of Contents 1 Using this Guide 2 From the Filmmaker 3 The Film 4 Background Information 5 Biographical Information on Whitney Young 6 The Leaders and Their Organizations 8 From Nonviolence to Black Power 9 How Far Have We Come? 10 Topics and Issues Relevant to The Powerbroker: Whitney Young’s Fight for Civil Rights 10 Thinking More Deeply 11 Suggestions for Action 12 Resources 13 Credits national center for MEDIA ENGAGEMENT Using this Guide Community Cinema is a rare public forum: a space for people to gather who are connected by a love of stories, and a belief in their power to change the world. This discussion guide is designed as a tool to facilitate dialogue, and deepen understanding of the complex issues in the film The Powerbroker: Whitney Young’s Fight for Civil Rights. It is also an invitation to not only sit back and enjoy the show — but to step up and take action. This guide is not meant to be a comprehensive primer on a given topic. Rather, it provides important context, and raises thought provoking questions to encourage viewers to think more deeply. We provide suggestions for areas to explore in panel discussions, in the classroom, in communities, and online. We also provide valuable resources, and connections to organizations on the ground that are fighting to make a difference. For information about the program, visit www.communitycinema.org DISCUSSION GUIDE // THE POWERBROKER 1 From the Filmmaker I wanted to make The Powerbroker: Whitney Young’s Fight for Civil Rights because I felt my uncle, Whitney Young, was an important figure in American history, whose ideas were relevant to his generation, but whose pivotal role was largely misunderstood and forgotten. -

Black Leaders on Leadership Conversations with Julian Bond

Black Leaders on Leadership Conversations with Julian Bond By Phyllis Leffler 4 December $32 | £17 | Paperback $105 | £66 | Hardcover “Leffler and Bond have put together a book of vital importance to the critical work of developing and fostering black leadership in America—it also happens to be a remarkably comprehensive account of the greatest movement for justice in American history. Like the Federal Writers' Project to compile slave narratives, Black Leaders on Leadership provides first-hand accounts of the valiant struggles of some of the most important activists America has ever produced. It should be required reading in the curriculum of every high school in America.” - Wade Henderson, President & CEO of The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, The Leadership Conference Education Fund The American civil rights movement of the 21st century produced some of the nation’s most influential black activists and leaders, many of whom are still working for positive social change today. In Black Leaders on Leadership, activist and politician Julian Bond and historian Phyllis Leffler use a rich portfolio of these leaders’ personal histories to weave an account of black leadership in America, aiming to inspire the next generation of leaders in the African American community. Drawing on a wealth of oral interviews collected by Bond and Leffler, Black Leaders on Black Leadership uses the lives of prominent African Americans from all sectors of society to trace the contours of black leadership in America. Included here are fascinating accounts from a wide variety of figures such as John Lewis, Clarence Thomas, Eleanor Holmes Norton, Vernon Jordan, Angela Davis, Amiri Baraka, and many more. -

OAAA E-Weekly Newsletters

OAAA E-Weekly Newsletter Office of African American Affairs February 4, 2019 Special Announcement History Makers: Black History 2019 The Office of African-American Affairs Black History Month Calendar is now available. Keep up-to-date on Black History Month event dates, times, and locations in the OAAA E-Weekly Newsletter. Have an item for the next newsletter? Submit it here! Mark Your Calendar Friday, March 1 - Application for Readmission for Summer and/or Fall Opens (Use the Form in SIS) Saturday, March 9 - Sunday, March 17 - Spring Recess Tuesday, April 30 - Courses end Wednesday, May 1 - Reading Day Thursday, May 2 - Friday, May 10 - Examinations Sunday, May 5; Wednesday, May 8 - Reading Days Friday, May 17 - Sunday, May 19 – Final Exercises Weekend OAAA Announcements & Services “Raising-the-Bar 4.0” Study & Tutoring Sessions- Spring 2019 Every Tuesday & Thursday – 4:00 pm-6:30 pm – W.E.B DuBois Center Conference Room. #2 Dawson’s Row. For questions, contact Raising-the-Bar Coordinator: Martha Demissew ([email protected] OAAA Biology & Chemistry Tutoring Every Thursday – 2:00-4:00 pm - W.E.B. DuBois Center Conference Room (Chemistry) Every Thursday – 4:00-6:00 pm - LPJ Black Cultural Center (Biology) Spanish support coming soon! RTB 4.0 – It’s Not Just for First Years’ Anymore Black Fridays Every Friday – 1:30 pm - LPJ Black Cultural Center #3 Dawson’s Row Come & join us for food & fellowship! Black College Women (BCW) Book Club Meetings Every Second & Fourth Sunday (Starting February 10) - 6:30 pm – Maury 113 Black President’s Council (BPC) Meetings Every Second & Fourth Monday (Starting February 11) – 6:30 pm – Newcomb Hall Board Rm 376 Black College Women (BCW) - In the Company of my Sister Every Wednesday (Starting February 22) - 12:00 pm - W.E.B Dubois Center Conference Room. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Vernon E

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Vernon E. Jordan, Jr. Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Jordan, Vernon E., 1935- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Vernon E. Jordan, Jr., Dates: January 24, 2003 Bulk Dates: 2003 Physical 3 Betacame SP videocasettes (1:27:30). Description: Abstract: Nonprofit chief executive and civil rights lawyer Vernon E. Jordan, Jr. (1935 - ) held various positions as a civil rights advocate, serving as the Georgia field secretary for the NAACP; the director of the Voter Education Project for the Southern Regional Council; the head of the United Negro College Fund; and as a delegate to President Lyndon B. Johnson’s White House Conference on Civil Rights. During the Clinton administration, Jordan became one of the most influential power brokers in Washington, D.C. Jordan was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on January 24, 2003, in Washington, District of Columbia. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2003_019 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Lawyer and Washington power broker Vernon Jordan was born on August 15, 1935, in Atlanta. Graduating with honors from David T. Howard High School in 1953, he went on to attend DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana, where he 1953, he went on to attend DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana, where he was the only African American student in his class. At DePauw, Jordan participated in the student senate, won statewide honors in speaking competitions, played basketball and graduated in 1957. -

Civil Rights Movement

Civil Rights Movement From the beginning, race has been at the heart of the deepest divisions in the United States and the greatest challenges to its democratic vision. Africans were brought to the continent in slavery, American Indian nations were subjected to genocidal wars of conquest, northwestern Mexico was invaded and annexed, Asians were imported as laborers then subjected to exclusionary laws. Black historian W.E.B. DuBois wrote that the history of the 20th Century would be the history of the color line, predicting that anti- colonial movements in Africa and Asia would parallel movements for full civil and political rights for people of color in the United States. During the 1920s and 1930s social scientists worked to replace the predominant biological paradigm of European racial superiority (common in Social Darwinism and eugenics) with the notion of ethnicity -- which suggested that racial minorities could follow the path of white European immigrant groups, assimilating into the American mainstream. Gunnar Myrdal's massive study An American Dilemma in 1944 made the case that the American creed of democracy, equality and justice must be extended to include blacks. Nathan Glazer and Daniel Moynihan argued in Beyond the Melting Pot in 1963 for a variation of assimilation based on cultural pluralism, in which various racial and ethnic groups retained some dimension of distinct identity. Following the civil rights movement's victories, neoconservatives began to argue in the 1970s that equal opportunity for individuals should not be interpreted as group rights to be achieved through affirmative action in the sense of preferences or quotas. -

Message to the Congress Transmitting a Report on the Prevention of Nuclear Proliferation May 16, 1994

Administration of William J. Clinton, 1994 / May 16 Message to the Congress Transmitting a Report on the Prevention of Nuclear Proliferation May 16, 1994 To the Congress of the United States: activities between January 1, 1993, and Decem- As required under section 601(a) of the Nu- ber 31, 1993. clear Non-Proliferation Act of 1978 (Public Law 95±242; 22 U.S.C. 3281(a)), I am transmitting WILLIAM J. CLINTON a report on the activities of United States Gov- ernment departments and agencies relating to The White House, the prevention of nuclear proliferation. It covers May 16, 1994. Remarks at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund Dinner May 16, 1994 Thank you, Elaine. Thank you, I think. It's That's what it said. And it said that about the pretty hard to follow Elaine Jones, especially schools. And I was thinking what a difference when she's on a roll like she was tonight. it had made. I was thinking tonight as Elaine [Laughter] And the rabbi, sounding more like gave me my report card on judges and told a Baptist preacher every day. [Laughter] And me to do a little betterÐ[laughter]Ðthat today, Vernon, who speaks well when he's asleep. since I have been privileged to be your Presi- [Laughter] And Dan Rather with a sense of dent, there is a new minority in the Nation: humor. [Laughter] A minority of those who have been appointed Ladies and gentlemen, I come here over- to the Federal bench are white men. A majority whelmingly to do one thing, to say on behalf are women and people of color. -

Remarks by the Honorable Dick Thornburgh, Attorney General of The

~tparfmtnt D~ ~ustit! POR l:HMEDl:ATE RELEASE 10:00 A.H. CDT JUNE 27, 198' REMARKS BY THE HONORABLE DICK THORNBURGH ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE UNITED STATES BEFORE OPERATION POSH ANNUAL CONFERENCE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS ~UESDAY, JUNE 27, 1987 The pursuit and promotion of civil rights in America is more than a legal obligation, it is a moral imperative embodied in our national sense of fairness and justice. with that imperative comes, of course, legal obligations, but it is important to remember that it is our sense of fairness and justice that drives our laws and not our laws which drive our sensitivities and sensibilities. The first and greatest truth of our Democratic society is set down in the stark and simple statement of our independence which declares that Hall men are created equal. H Those five words frame the charter of the united States Department of Justice in our endeavors to ensure that all Americans men and women, black, brown and white, young and old, able or with disability -- enjoy their full civil rights. Let me assure you, this is an assignment that President Bush and I take very seriously. This morning I would like to touch on just a few matters that I think will give you a better appreciation of our approach to civil rights concerns and for the type of constructive cooperation we are trying to achieve with those who share those concerns. First, and possibly most important during these early months of this Administration, we have sought to re-establish a constructive dialogue with civil rights and minority groups -- of all persuasions and backgrounds. -

Memphis Voices: Oral Histories on Race Relations, Civil Rights, and Politics

Memphis Voices: Oral Histories on Race Relations, Civil Rights, and Politics By Elizabeth Gritter New Albany, Indiana: Elizabeth Gritter Publishing 2016 Copyright 2016 1 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………..3 Chapter 1: The Civil Rights Struggle in Memphis in the 1950s………………………………21 Chapter 2: “The Ballot as the Voice of the People”: The Volunteer Ticket Campaign of 1959……………………………………………………………………………..67 Chapter 3: Direct-Action Efforts from 1960 to 1962………………………………………….105 Chapter 4: Formal Political Efforts from 1960 to 1963………………………………………..151 Chapter 5: Civil Rights Developments from 1962 to 1969……………………………………195 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………..245 Appendix: Brief Biographies of Interview Subjects…………………………………………..275 Selected Bibliography………………………………………………………………………….281 2 Introduction In 2015, the nation commemorated the fiftieth anniversary of the Voting Rights Act, which enabled the majority of eligible African Americans in the South to be able to vote and led to the rise of black elected officials in the region. Recent years also have seen the marking of the 50th anniversary of both the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed discrimination in public accommodations and employment, and Freedom Summer, when black and white college students journeyed to Mississippi to wage voting rights campaigns there. Yet, in Memphis, Tennessee, African Americans historically faced few barriers to voting. While black southerners elsewhere were killed and harassed for trying to exert their right to vote, black Memphians could vote and used that right as a tool to advance civil rights. Throughout the 1900s, they held the balance of power in elections, ran black candidates for political office, and engaged in voter registration campaigns. Black Memphians in 1964 elected the first black state legislator in Tennessee since the late nineteenth century. -

Vernon Jordan, Jr

Tuesday. May 12. 1981 Volume 27, Number 33 Six Honorary Degree Recipients Civil rights leader Vernon E. Jordan. Jr. (right), author James Baldwin and Penn's emi- nent Indian art scholar Stella Kramrisch will be among six honorary degree recipients at the University's 225th Commencement. May 18. With them will be MIT educator and neuroscientist Francis Otto Schmitt. historian and educator John Hope Franklin of Chicago, and the Rt. Rev. Lyman C. Ogilby. Episcopal Bishop of the Diocese of Pennsylvania, who is also this year's Baccalaureate speaker. Mr. Jordan, president of the National Urban League. will give the Commencement Ad- dress at Monday's ceremony in the Civic Cen- ter, which begins with a student procession at 1981-82 Salaries 10 a.m. and academic procession at 10:30 In two separate memoranda presented to- a.m. His daughter, Vickee, a graduating sen- gether on page 2. the Office of the Provost has ior in the FAS, will be among the more than issued salary guidelines for 1981-82 that give 3.500 students receiving degrees. each school and center budget a 10 percent in- Mr. Jordan has directed the National Urban crease in salary funds, but outline different League since 1972. His weekly column, "To formulas for its distribution to academic and Be Equal." appears in approximately 200 nonacademic personnel. newspapers and his radio commentaries are Standing faculty will have a base increase of broadcast three times a week on the Westing- at 8 percent with the remaining two percent dis- house Broadcasting Network. He is a fellow of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology cretionary. -

11/13/75 - National Council of Negro Women” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 4, folder “11/13/75 - National Council of Negro Women” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Betty Ford donated to the United States of America her copyrights in all of her unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. CALL TO CONVENTION One hundred years ago Mary Mcleod Bethune was born of slave parents in Mayesville, South Carolina. She dedicated her life to her people, her nation, her world. From her magnificent dream of uniting women of diverse backgrounds and interests she founded the National Council of Negro Women. In her Last Will and Testament, Mary Mcleod Bethune left the essence of her philosophy of life and living, in the heart of her legacy- "! Leave you Love I Leave you Hope I Leave you the Challenge of developing Confidence in one another I Leave you a Thirst for Education I Leave you Respect for the use of Power I Leave you Faith I Leave you Racial Dignity I Leave you a Desire to live harmoniously with your fellow man I Leave you, Finally a responsibility to our young people." Mary Mcleod Bethune challenged women in the Black community, and all women, to work with a unity of purpose and unity of action to achieve their rights and opportunities in education, employ ment, housing , health, and self-fulfillment and to use their combined strength for the betterment of community, national and international life. -

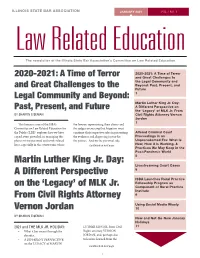

Martin Luther King Jr. Day: a Different Perspective on Past, Present, and Future the ‘Legacy’ of MLK Jr

ILLINOIS STATE BAR ASSOCIATION JANUARY 2021 VOL 7 NO. 3 Law Related Education The newsletter of the Illinois State Bar Association’s Committee on Law Related Education 2020-2021: A Time of Terror 2020-2021: A Time of Terror and Great Challenges to the Legal Community and Beyond: Past, Present, and and Great Challenges to the Future Legal Community and Beyond: 1 Martin Luther King Jr. Day: A Different Perspective on Past, Present, and Future the ‘Legacy’ of MLK Jr. From BY SHARON EISEMAN Civil Rights Attorney Vernon Jordan 1 This January issue of the ISBA’s the lawyers representing their clients and Committee on Law Related Education for the judges overseeing that litigation must the Public (‘LRE’) explores how we have continue their respective roles in presenting Altered Criminal Court coped, even prevailed, in managing the the evidence and dispersing justice for Proceedings in an phases of our personal and work-related the parties. And on the personal side, Unprecedented Era: What Is lives, especially in the courtrooms where Continued on next page New, How it Is Working, & Practices We May Keep in the Post-Pandemic World Martin Luther King Jr. Day: 5 Livestreaming Court Cases A Different Perspective 6 ISBA Launches Rural Practice Fellowship Program as on the ‘Legacy’ of MLK Jr. Component of Rural Practice Institute From Civil Rights Attorney 9 Using Social Media Wisely Vernon Jordan 10 BY SHARON EISEMAN New and Not-So-New January Holidays 2021 and THE MLK JR. HOLIDAY: LUTHER KING JR. from Civil 11 • What it has meant through the Rights attorney VERNON decades, JORDAN, and, perhaps due • A DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVE to lessons learned from the on the ‘LEGACY’ of MARTIN Continued on next page 1 Law Related Education ▼ JANUARY 2021 / VOL 7 / NO.