Assessing the Costs of the Pedestrianization of Avenida in the City of Manila

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resettlement Plan PHI: EDSA Greenways Project (Balintawak

Resettlement Plan February 2020 PHI: EDSA Greenways Project (Balintawak Station) Prepared by Department of Transportation for the Asian Development Bank. This resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (As of 30 January 2020; Central Bank of the Philippines) Philippine Peso (PhP) (51.010) = US $ 1.00 ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank AH Affected Household AO Administrative Order AP Affected Persons BIR Bureau of Internal Revenue BSP Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas CA Commonwealth Act CGT Capital Gains Tax CAP Corrective Action Plan COI Corridor of Impact DA Department of Agriculture DAO Department Administrative Order DAR Department of Agrarian Reform DAS Deed of Absolute Sale DBM Department of Budget and Management DDR Due Diligence Report DED Detailed Engineering Design DENR Department of Environment and Natural Resources DILG Department of Interior and Local Government DMS Detailed Measurement Survey DO Department Order DOD Deed of Donation DOTr Department of Transportation DPWH Department of -

List of Participating Petron Service Stations September 6

LIST OF PARTICIPATING PETRON SERVICE STATIONS SEPTEMBER 6 - 21, 2021 REGION CITY / MUNICIPALITY ADDRESS METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY 245 SUSANO ROAD, DEPARO KALOOKAN CITY METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY ZABARTE ROAD, BRGY. CAMARIN, NORTH CALOOCAN, KALOOKAN CITY METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY 146RIZAL AVENUE EXT. GRACE PARK CALOOCAN CITY METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY 510 A. MABINI ST., KALOOKAN CITY METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY C-3 ROAD, DAGAT-DAGATAN CALOOCAN CITY METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY BLK 46 CONGRESSIONAL ROAD EXT., BAG CALOOCAN CITY METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY B. SERRANO ST. COR 11TH AVE CALOOCAN CITY METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY GEN. SAN MIGUEL ST., SANGANDAAN, CALOOCAN CITY METRO MANILA LAS PINAS ALABANG ZAPOTE ROAD LAS PINAS, METRO MANILA METRO MANILA LAS PINAS LOT 2A DAANG HARI CORNER DAANG REYN LAS PINAS METRO MANILA LAS PINAS NAGA ROAD LAS PINAS CITY, METRO MANILA METRO MANILA LAS PINAS BLK 14 LOT 1 VERSAILLES SUBD DAANG LAS PIбAS CITY METRO MANILA LAS PINAS CRM AVENUE, BF ALMANZA, LAS PIбAS METRO MANILA METRO MANILA LAS PINAS LOT 1 & 2 J. AGUILAR AVENUE TALON TRES, LAS PINAS METRO MANILA LAS PINAS ALABANG ZAPOTE RD., PAMPLONA LAS PINAS METRO MANILA LAS PINAS 269 REAL ST. PAMPLONA LAS PINAS METRO MANILA LAS PINAS 109 MARCOS ALVAREZ AVE. TALON LAS PINAS METRO MANILA LAS PINAS 469 REAL ST., ZAPOTE LAS PINAS METRO MANILA MAKATI CITY 46 GIL PUYAT AVE. NEAR COR. DIAN MAKATI CITY METRO MANILA MAKATI CITY G PUYAT COR P TAMO AVE, MAKATI CITY METRO MANILA MAKATI CITY LOT 18 BLOCK 76 SEN. GIL PUYAT AVE. PALANAN, MAKATI CITY METRO MANILA MAKATI CITY PETRON DASMARINAS STATION EDSA, MAKATI CITY METRO MANILA MAKATI CITY 363 SEN. -

Assessment of Impediments to Urban-Rural Connectivity in Cdi Cities

ASSESSMENT OF IMPEDIMENTS TO URBAN-RURAL CONNECTIVITY IN CDI CITIES Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project CONTRACT NO. AID-492-H-15-00001 JANUARY 27, 2017 This report is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of the International City/County Management Association (ICMA) and do not necessarily reflect the view of USAID or the United States Agency for International Development USAID Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project Page i Pre-Feasibility Study for the Upgrading of the Tagbilaran City Slaughterhouse ASSESSMENT OF IMPEDIMENTS TO URBAN-RURAL CONNECTIVITY IN CDI CITIES Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project CONTRACT NO. AID-492-H-15-00001 Program Title: USAID/SURGE Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Philippines Contract Number: AID-492-H-15-00001 Contractor: International City/County Management Association (ICMA) Date of Publication: January 27, 2017 USAID Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project Page ii Assessment of Impediments to Urban-Rural Connectivity in CDI Cities Contents I. Executive Summary 1 II. Introduction 7 II. Methodology 9 A. Research Methods 9 B. Diagnostic Tool to Assess Urban-Rural Connectivity 9 III. City Assessments and Recommendations 14 A. Batangas City 14 B. Puerto Princesa City 26 C. Iloilo City 40 D. Tagbilaran City 50 E. Cagayan de Oro City 66 F. Zamboanga City 79 Tables Table 1. Schedule of Assessments Conducted in CDI Cities 9 Table 2. Cargo Throughput at the Batangas Seaport, in metric tons (2015 data) 15 Table 3. -

Urban Transportation in Metropolitan Manila*

PHILIPPINE PLANNING JOURNAL I~ <1&~'V ..." z (/) ~ SCHOOL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL PLANNING • VOL. XVII, NO.1, OCTOBER 1985 • THE METRORAIL SYSTEM PHILIPPINE PLANNING JOURNAL VOL. XVII, No.1, Oct. 1985 Board of Editors Dolores A. Endriga Tito C. Firmalino Jaime U. Nierras Managing Editor Production Manager Carmelita R. E. U. Liwag Delia R. Alcalde Circulation & Business Manager Emily M. Mateo The Philippine Planning Journal is published in October and April by the School of Urban and Regional Planning, University of the Philippines. Views and opinions expressed in signed articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the School of Urban and Regional Planning. All communications should be addressed to the Business Manager, Philippine Planning Journal, School of Urban & Regional Planning, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines 1101. Annual Subscription Rate: Domestic, fl40.00; Foreiqn, $12.00. Single copies: Domestic, "20.00; Foreign, $6.00. Back issues: Domestic, fl10.00/issue; Foreign, $6.00Iissue. TABLE OF CONTENTS Urban Tansportation in Metropolitan Manila Selected Officials of the Ministry of Trans portation and Communications 20 Pedestrianization of a City Core and the Light Rail Transit Victoria Aureus-Eugenio 33 The LRT as a Component of Metro Manila's Trans port Systems - Ministry of Transport and Communications 46 Urban Land Management Study: Urban Redevelop ment in Connection with Metrorail Office of the Commissioner for Planning, Metro Manila Commission 57 Philippine Planning -

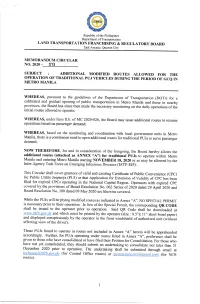

Additional Modified Routes Allowed for the Operation of Traditional

Republic of the Philippircs Department of Transportation LAND TRANSPORTATION FRANCHISING & REGULATORY BOARI) East Avenue, Quezon City MEMORANDUM CIRCULAR NO.2020 - 013 SUBJECT ADDITIONAL MODIFIED ROUTES ALLOWED FOR THE OPERATION OF TR,{DITIONAL PUJ VEHICLES DURING THE PERIOD OF GCQ IN METRO MANILA WHEREAS, pursuant to the guidelines of the Department of Transportation (DOTr) for a calibrated and gradual opening of public transportation in Metro Manila and those in nearby provinces, the Board has since then made the necessary monitoring on the daily operations of thl initial routes allowed to operate; WHEREAS, under Item II.b. of MC 2020-O26,the Board may issue additional routes to resume operations based on passenger demand; WHEREAS, based on the monitoring and coordination with local government urits in Metro Manila, there is a continuous need to open additional routes for kaditional PUJs to sorye passenger demand; NOW TIIEREF0RE, for and in consideration of the foregoing the Board" hereby allows the additional routes (attached as ANNEX "A") for traditional PUJs to operate within Metro Manila and entering Metro Manila starting NOVEMBER 18, 2020 or u. *uy be allowed by the Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases (rATF-EIF) This Circular shall cover grantees of valid and existing Certificate of Public Convenience (CpC) for Public Utility Jeepneys (PUJ) or that Application for Extension of Validity of CpC has been filed for expired CPCs operating in the National Capital Region. Operators with expired CpC covered by the provisions of Board Resolution No. 062 Series of 202A dated 29 Aprii 2A20 and, Board Resolution No. 100 dated 09 May 2a20 arc tikswise coversd. -

1623400766-2020-Sec17a.Pdf

COVER SHEET 2 0 5 7 3 SEC Registration Number M E T R O P O L I T A N B A N K & T R U S T C O M P A N Y (Company’s Full Name) M e t r o b a n k P l a z a , S e n . G i l P u y a t A v e n u e , U r d a n e t a V i l l a g e , M a k a t i C i t y , M e t r o M a n i l a (Business Address: No. Street City/Town/Province) RENATO K. DE BORJA, JR. 8898-8805 (Contact Person) (Company Telephone Number) 1 2 3 1 1 7 - A 0 4 2 8 Month Day (Form Type) Month Day (Fiscal Year) (Annual Meeting) NONE (Secondary License Type, If Applicable) Corporation Finance Department Dept. Requiring this Doc. Amended Articles Number/Section Total Amount of Borrowings 2,999 as of 12-31-2020 Total No. of Stockholders Domestic Foreign To be accomplished by SEC Personnel concerned File Number LCU Document ID Cashier S T A M P S Remarks: Please use BLACK ink for scanning purposes. 2 SEC Number 20573 File Number______ METROPOLITAN BANK & TRUST COMPANY (Company’s Full Name) Metrobank Plaza, Sen. Gil Puyat Avenue, Urdaneta Village, Makati City, Metro Manila (Company’s Address) 8898-8805 (Telephone Number) December 31 (Fiscal year ending) FORM 17-A (ANNUAL REPORT) (Form Type) (Amendment Designation, if applicable) December 31, 2020 (Period Ended Date) None (Secondary License Type and File Number) 3 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION SEC FORM 17-A ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 17 OF THE SECURITIES REGULATION CODE AND SECTION 141 OF CORPORATION CODE OF THE PHILIPPINES 1. -

JEEP Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

JEEP bus time schedule & line map JEEP Jolibee, Macarthur Highway, Malinta, Valenzuela View In Website Mode City →Plaza Santa Cruz, Manila City The JEEP bus line (Jolibee, Macarthur Highway, Malinta, Valenzuela City →Plaza Santa Cruz, Manila City) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Jolibee, Macarthur Highway, Malinta, Valenzuela City →Plaza Santa Cruz, Manila City: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM (2) Rizal Avenue, Manila →Jolibee, Macarthur Highway, Malinta, Valenzuela City: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest JEEP bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next JEEP bus arriving. Direction: Jolibee, Macarthur Highway, Malinta, JEEP bus Time Schedule Valenzuela City →Plaza Santa Cruz, Manila City Jolibee, Macarthur Highway, Malinta, Valenzuela 54 stops City →Plaza Santa Cruz, Manila City Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Jolibee, Macarthur Highway, Malinta, Valenzuela City Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Malinta Elementary School, Macarthur Highway, Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Malinta, Valenzuela City Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Macarthur Highway / Maysan Road Intersection, Friday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Malinta, Valenzuela City Maysan Road, Philippines Saturday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM Flying V Gas, Macarthur Highway, Valenzuela City South Supermarket, Macarthur Highway, Valenzuela City JEEP bus Info Direction: Jolibee, Macarthur Highway, Malinta, Macarthur Highway, 283a Valenzuela City →Plaza Santa Cruz, Manila City Stops: 54 Karuhatan Public Market, -

JEEP Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

JEEP bus time schedule & line map Jolibee, Macarthur Highway, Malinta, Valenzuela JEEP City →Lrt Doroteo Jose-Recto Station Walkway / View In Website Mode Rizal Avenue Intersection, Manila The JEEP bus line (Jolibee, Macarthur Highway, Malinta, Valenzuela City →Lrt Doroteo Jose-Recto Station Walkway / Rizal Avenue Intersection, Manila) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Jolibee, Macarthur Highway, Malinta, Valenzuela City →Lrt Doroteo Jose-Recto Station Walkway / Rizal Avenue Intersection, Manila: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM (2) Oroquieta, Manila →Jolibee, Macarthur Highway, Malinta, Valenzuela City: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest JEEP bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next JEEP bus arriving. Direction: Jolibee, Macarthur Highway, Malinta, JEEP bus Time Schedule Valenzuela City →Lrt Doroteo Jose-Recto Station Jolibee, Macarthur Highway, Malinta, Valenzuela Walkway / Rizal Avenue Intersection, Manila City →Lrt Doroteo Jose-Recto Station Walkway / 51 stops Rizal Avenue Intersection, Manila Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Jolibee, Macarthur Highway, Malinta, Valenzuela City Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Malinta Elementary School, Macarthur Highway, Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Malinta, Valenzuela City Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Macarthur Highway / Maysan Road Intersection, Friday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Malinta, Valenzuela City Maysan Road, Philippines Saturday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM Flying V Gas, Macarthur Highway, Valenzuela -

ACCREDITED TRAINING CENTERS for ASSESSMENT of ERSC As of August 31, 2011

ACCREDITED TRAINING CENTERS FOR ASSESSMENT OF ERSC As of August 31, 2011 NEW SIMULATOR CENTER OF THE PHILIPPINES INC. (NSCPI) 5th Floor 2053 Bldg., Edison St., Makati City Tel# 888-27-64/ 888-27-94 EXACT 4th Floor MSIR Bldg. P. Paredes cor. Loyola St., Sampaloc, Manila Tel# 733-21-19/ 733-88-97 PROFOUND – MASTER Ground Floor, NWFC Bldg., #958 Escoda St., Ermita Manila Tel# 536-48-02 PROTECT 925-C Aragon cor. Leon Guinto St., Malate, Manila Tel# 527-4783/ 3097834 INTERSHIP NAVIGATION TRAINING CENTER, INC. (INTCS) 2nd Floor CRI Bldg., Pres. Quirino Ave., Malate, Manila Tel# 522-34-77/521-93-06 MARITIME ACADEMY OF ASIA AND THE PACIFIC (MAAP ) Associated Marine Officers and Seamen’s Union of the Philippines PTGWO-ITF Kamaya Point, Brgy. Alas-asin Mariveles, Bataan FAREAST MARITIME FOUNDATION, INC. (PHILCAMSAT) 2nd Floor First Maritime Place 7458 Bagtican St., San Antonio Village, Makati City Tel# 898-1111/8981179 SANDIGAN SHIPS SERVICES, INC. 9TH Floor Salustiana D. Ty Tower 104 Paseo De Roxas cor. Perea St. Legaspi Village, Makati City Tel# 894-28-21 to 24 NYK-FIL MARITIME E-TRAINING, INC. Gen. Luna cor. Sta. Potenciana St., Intramuros Manila Tel# 527-2268 “K” LINE MARITIME ACADEMY PHILIPPINES INC. Coral Way Drive, Central Business Park 1 Bay City, Pasay City Tel# 556-2917 to 20 PHILIPPINE CENTER FOR ADVANCED MARITIME SIMULATION AND TRAINING, INC. (PHILCAMSAT) 2nd Floor First Maritime Place 7458 Bagtican St., San Antonio Village, Makati City Tel# 898-1111/ 8981179 ZRC TRAINING CENTER PHILS. INC. G/F Rm. 108 Ermita Center Bldg., Roxas Blvd., cor Sta. -

Top 100 Stockholders As of June 30, 2011

BPI STOCK TRANSFER OFFICE MANCHESTER INTERNATIONAL HOLDINGS UNLIMITED CORP. TOP 100 STOCKHOLDERS AS OF JUNE 30, 2011 RANK STOCKHOLDER NUMBER STOCKHOLDER NAME NATIONALITY CERTIFICATE CLASS OUTSTANDING SHARES PERCENTAGE TOTAL 1 09002935 INTERPHARMA HOLDINGS & MANAGEMENT CORPORATION FIL A 255,264,483 61.9476% 255,264,483 C/O INTERPHIL LABORATORIES INC KM. 21 SOUTH SUPERHIGHWAY 1702 SUKAT, MUNTINLUPA, M. M. 2 1600000001 PHARMA INDUSTRIES HOLDINGS LIMITED BRT B 128,208,993 31.1138% 128,208,993 C/O ZUELLIG BUILDING, SEN. GIL J. PUYAT AVENUE, MAKATI CITY 3 16015506 PCD NOMINEE CORPORATION (FILIPINO) FIL A 10,969,921 G/F MKSE. BLDG, 6767 AYALA AVE MAKATI CITY B 8,258,342 4.6663% 19,228,263 4 16009811 PAULINO G. PE FIL A 181,250 29 NORTH AVENUE, DILIMAN, QUEZON CITY B 575,000 0.1835% 756,250 5 10002652 KASIGOD V. JAMIAS FIL A 464,517 109 APITONG ST., AYALA ALABANG MUNTINLUPA, METRO MANILA B 106,344 0.1385% 570,861 6 16011629 PCD NOMINEE CORPORATION (NON-FILIPINO) NOF B 393,750 0.0955% 393,750 G/F MKSE BUILDING 6767 AYALA AVENUE MAKATI CITY 7 16010090 PUA YOK BING FIL A 375,000 0.0910% 375,000 509 SEN. GIL PUYAT AVE. EXT. NORTH FORBES PARK MAKATI CITY 8 16009868 PAULINO G. PE FIL B 240,000 0.0582% 240,000 29 NORTH AVENUE, DILIMAN, QUEZON CITY 9 03030057 ROBERT S. CHUA FIL A 228,750 0.0555% 228,750 C/O BEN LINE, G/F VELCO CENTER R.S. OCA ST. COR. A.C. DELGADO PORT AREA, MANILA 10 03015970 JOSE CUISIA FIL A 187,500 0.0455% 187,500 C/O PHILAMLIFE INSURANCE CO. -

Study on Medium Capacity Transit System Project in Metro Manila, the Republic of the Philippines

Study on Economic Partnership Projects in Developing Countries in FY2014 Study on Medium Capacity Transit System Project in Metro Manila, The Republic of The Philippines Final Report February 2015 Prepared for: Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry Ernst & Young ShinNihon LLC Japan External Trade Organization Prepared by: TOSTEMS, Inc. Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd. Japan Transportation Planning Association Reproduction Prohibited Preface This report shows the result of “Study on Economic Partnership Projects in Developing Countries in FY2014” prepared by the study group of TOSTEMS, Inc., Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd., Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd. and Japan Transportation Planning Association for Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. This study “Study on Medium Capacity Transit System Project in Metro Manila, The Republic of The Philippines” was conducted to examine the feasibility of the project which construct the medium capacity transit system to approximately 18km route from Sta. Mesa area through Mandaluyong City, Ortigas CBD and reach to Taytay City with project cost of 150 billion Yen. The project aim to reduce traffic congestion, strengthen the east-west axis by installing track-guided transport system and form the railway network with connecting existing and planning lines. We hope this study will contribute to the project implementation, and will become helpful for the relevant parties. February 2015 TOSTEMS, Inc. Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. Mitsubishi Heavy -

2015Suspension 2008Registere

LIST OF SEC REGISTERED CORPORATIONS FY 2008 WHICH FAILED TO SUBMIT FS AND GIS FOR PERIOD 2009 TO 2013 Date SEC Number Company Name Registered 1 CN200808877 "CASTLESPRING ELDERLY & SENIOR CITIZEN ASSOCIATION (CESCA)," INC. 06/11/2008 2 CS200719335 "GO" GENERICS SUPERDRUG INC. 01/30/2008 3 CS200802980 "JUST US" INDUSTRIAL & CONSTRUCTION SERVICES INC. 02/28/2008 4 CN200812088 "KABAGANG" NI DOC LOUIE CHUA INC. 08/05/2008 5 CN200803880 #1-PROBINSYANG MAUNLAD SANDIGAN NG BAYAN (#1-PRO-MASA NG 03/12/2008 6 CN200831927 (CEAG) CARCAR EMERGENCY ASSISTANCE GROUP RESCUE UNIT, INC. 12/10/2008 CN200830435 (D'EXTRA TOURS) DO EXCEL XENOS TEAM RIDERS ASSOCIATION AND TRACK 11/11/2008 7 OVER UNITED ROADS OR SEAS INC. 8 CN200804630 (MAZBDA) MARAGONDONZAPOTE BUS DRIVERS ASSN. INC. 03/28/2008 9 CN200813013 *CASTULE URBAN POOR ASSOCIATION INC. 08/28/2008 10 CS200830445 1 MORE ENTERTAINMENT INC. 11/12/2008 11 CN200811216 1 TULONG AT AGAPAY SA KABATAAN INC. 07/17/2008 12 CN200815933 1004 SHALOM METHODIST CHURCH, INC. 10/10/2008 13 CS200804199 1129 GOLDEN BRIDGE INTL INC. 03/19/2008 14 CS200809641 12-STAR REALTY DEVELOPMENT CORP. 06/24/2008 15 CS200828395 138 YE SEN FA INC. 07/07/2008 16 CN200801915 13TH CLUB OF ANTIPOLO INC. 02/11/2008 17 CS200818390 1415 GROUP, INC. 11/25/2008 18 CN200805092 15 LUCKY STARS OFW ASSOCIATION INC. 04/04/2008 19 CS200807505 153 METALS & MINING CORP. 05/19/2008 20 CS200828236 168 CREDIT CORPORATION 06/05/2008 21 CS200812630 168 MEGASAVE TRADING CORP. 08/14/2008 22 CS200819056 168 TAXI CORP.