B. R. Ambedkar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A South Asian Movement's Social

Justpeace Prospects for Peace-building and Worldview Tolerance: A South Asian Movement’s Social Construction of Justice A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University By Jeremy A. Rinker Master of Arts University of Hawaii, 2001 Bachelor of Arts University of Pittsburgh, 1995 Director: Dr. Daniel Rothbart, Professor of Conflict Resolution Institute for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Spring Semester 2009 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright: 2009 Jeremy A. Rinker All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to the many named and unnamed dalits who have endured the suffering and humiliation of centuries of social ostracism, discrimination, and structural violence. Their stories, though largely unheard, provide both an inspiration and foundation for creating social justice. It is my hope that in telling and analyzing the stories of dalit friends associated with the Trailokya Bauddha Mahasangha, Sahayak Gana (TBMSG), both new perspectives and a sense of hope about the ideal of justpeace will be fostered. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank all those that provided material, emotional, and spiritual support to me during the many stages of this dissertation work (from conceptualization to completion). The writing of a dissertation is a lonely process and those that suffer most during such a solitary process are invariably the writer’s family. Therefore, special thanks are in order for my wife Stephanie and son Kylor. Thank you for your devotion, understanding, and encouragement throughout what was often a very difficult process. I will always regret the many Saturday trips to the park that I missed, but I promise to make them up as best I can as I begin my new life as Dr. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

Dr. Bhimrao R Ambedkar and Nelson R Mandela-The Similarities and Contrast in the Movement of Two Icons of 20Th Century Fought for Suppressed

DR. BHIMRAO R AMBEDKAR AND NELSON R MANDELA-THE SIMILARITIES AND CONTRAST IN THE MOVEMENT OF TWO ICONS OF 20TH CENTURY FOUGHT FOR SUPPRESSED DR. DHARMAJI KHARAT Sr. Faculty in English P.V.P., Sndt Women’s University, Juhu, Santacruz (West), MUMBAI -49 (MS) INDIA Caste is inner and hidden discrimination whereas race is outer and open discrimination. Inner and hidden discrimination is more dangerous than the open one. Discrimination of gender is the experience of all families. Every person has concern for and together all people can take a firm stand against the cases of gender discrimination happens in any part of the country and the world. But, caste discrimination is the problem of particular groups of people and it can’t be the experience of all. Therefore, only the victimized and marginal groups of people come together to fight against caste discrimination happens. People belonging to non SC/ST do not standby the sufferer. On the contrary, many educated stupid believe in caste system. Starting from M.K. Gandhi to every Indian, we, the Indians have open heartedly supported the mission of Dr.Nelson Mandela. Because we are blacks and we knew that Mandela fights for equality so we supported. But, the same higher class black feels proud and happy to exploit other backward class blacks in their own country. Blacks are everywhere throughout the world therefore, almost all the nations representative have supported the mission of Mandela. Caste-system exists in India and Dr. B.R. Ambedkar was one man army who fought the battle against established. -

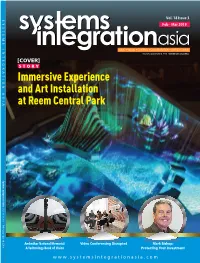

Immersive E and Art Inst at Reem Cen Immersive Experience and Art

SS Y Y S S T T E E M M S S II N N T T E E G G R R A A T T I I O O N N AA S S I I A A Vol.18Issue3Vol.18Issue3 Feb-Mar2019Feb-Mar2019 MCIMCI (P) (P) 023/04/2018 023/04/2018 PPS PPS 1669/08/2013(022992) 1669/08/2013(022992) [COVER][COVER] STORYSTORY ImmersiveImmersive ExperienceExperience andand ArtArt InstallationInstallation atat ReemReem CentralCentral ParkPark SystemsIntegrationAsia SystemsIntegrationAsia Vol.18Issue 3~ Vol.18Issue 3~ February-March2019 February-March2019 AmbedkarAmbedkar National National Memorial: Memorial: VideoVideo Conferencing Conferencing Disrupted Disrupted MarkMark Bishop: Bishop: AA Technology Technology Book Book of of Vision Vision ProtectingProtecting Your Your Investment Investment www.systemsintegrationasia.comwww.systemsintegrationasia.com CONTENTS Vol.18Issue3~February-March2019 Ambedkar National Memorial: A Technology Book of Vision 60 04 FIRST WORDS 54 INTERVIEW 80 VOICE BOX 06 NEWS The Right Touch is Central to Today's Retail LynTec: Protecting Your Investment Customer Journey 56 INSTALLATIONS 82 ON OUR WEB 36 EVENTS 56 ABU DHABI: Immersive Experience and Art Installation at Reem Central Park 36 AVCL III: A Reinforcing Statement of its Own 59 VIETNAM: Symetrix Radius Chosen for 40 'Women of AV' Make a 'Marathon' Leap angelina Bar and Restaurant 60 42 Epson Holds Event for Regional Partners INDIA: Ambedkar National Memorial in Bangkok - A Technology Book of Vision 68 KUWAIT: KMT - The Integrated Motoracing Township 44 SOLUTIONS UPDATE 74 INDIA: Rivera Does an Avant-Garde Audio at NID 76 AUSTRALIA: Lendlease Creates Versatile Meeting and Collaborative Workspaces for Better Productivity and Efciency 52 FEATURE 78 TECH TALK Video Conferencing Disrupted Evaluating and Selecting the Best Monitoring Method 4 FIRST WORDS December and January saw many acquisition news. -

Ratnagiri !( Ambavane Bk

Mhasla Village Map Taluka: Mandangad Mhapral Dandnagari Umbershet Padwe Kondgaon Lokran Mahad District: Ratnagiri !( Ambavane Bk. Islampur Pewe Adkhalvan Shrivardhan Kumbharli Bahiravali Panderi Kinjalghar Govele Shigvan Buri Ghumari Panhali Kh. Asawale Takavali Chinchali Dhangar Nigadi Vakavali Ambadawe Pat BHAmghar Surle Shenale µ Ghosale Adkhal Soweli Gothe Kuduk Kh. 3 1.5 0 3 6 9 A Borkhat Sawari Konzar km Mandangad Terdi Veral Tarf Veshwi Shirgaon Shipole Bandar Pale MANDANGAD Pacharal Valmiki Nagar Kalkavane !( Bhingaloli Dhutroli Veshvi Dhamani Sade Creek Bankot Umroli Kuduk Bk. R Shipole Location Index Kante Konhavali Kengwal Gawalwadi Keril Devhare Borghar Palghar Narayannagar Gudeghar Mahu Takede Kelwat Taleghar Tulshi Tide Ambavane Kh. District Index Velas Kawale Tarf Vinhere Nandurbar Ranavali Tamhane Panhali Bk. Nayane Bhandara Ambavali Chinchaghar Kadawan Vadavali Bamanghar Dhule Amravati Nagpur Gondiya Kumbale Jalgaon A Sakhari Jawale Valote Akola Wardha Atale Unhavare Nargoli Buldana Sheware Dudhere Pimpaloli Nashik Washim Chandrapur Dahimbe Latawan Yavatmal Palghar Aurangabad Palawani DabhatMuradpur Jalna Hingoli Gadchiroli Shirsavane Tondali Thane Ahmednagar Parbhani Mumbai Suburban Nanded Bid Dattanagar Gowal Mumbai Gharadi Dahagaon Vinhe Raigarh Pune B Veral Tarf Natu Latur Bidar Shedawai Pimpalgaon Osmanabad Satara Solapur Jambul Nagar Bholavali Ratnagiri Sangli Maharashtra State Kolhapur I Sindhudurg Dharwad Taluka Index Mandangad A Dapoli Khed Guhagar Chiplun N Dapoli Sangameshwar Ratnagiri Legend Lanja !( Taluka Head Quarter S Rajapur Railway District: Ratnagiri National Highway State Highway Village maps from Land Record Department, GoM. E Khed Data Source: State Boundary Waterbody/River from Satellite Imagery. District Boundary Generated By: Taluka Boundary Maharashtra Remote Sensing Applications Centre A Village Boundary Autonomous Body of Planning Department, Government of Maharashtra, VNIT Campus, Waterbody/River South Am bazari Road, Nagpur 440 010. -

14. Formation of State of Maharashtra

14. Formation of State of Maharashtra After India gained independence, there was demand on large scale for the reconstruction of states on linguistic basis. In Maharashtra also the demand for state of Marathi speaking people led to ‘Samyukta Maharashtra Movement’ from 1946 onwards. Through various changing circumstances the movement progressed and finally on 1 May 1960 the state of Maharashtra came to be formed. Background : From the beginning of 20th century, many scholars had begun to express the thoughts on unification of Marathi speaking people. In 1911, the British Government had to suspend the partition of Bengal. On this background, N.C.Kelkar wrote that ‘the entire Marathi speaking poulation should be under one dominion’. In 1915, Lokmanya Tilak had demanded the reconstruction of a state based on language. But during that period the issue of independence of India was more important, hence this issue remained aside. On 12 May 1946, in the Sahitya Sammelan at Belgaon, an important resolution regarding Samyukta Maharashtra was passed. Samyukta Maharashtra Parishad : On 28 July, ‘Maharashtra Ekikaran Parishad’ was called at Mumbai. Shankarrao Dev was its president. It passed a resolution that all Marathi speaking regions should be included in one state. This should also include Marathi speaking regions of Mumbai, Central provinces as well as Marathwada and Gomantak. Dar Commission : On 17 June 1947, Dr. Rajendra Prasad, the President of Constituent Assembly established the ‘Dar Commission’ under the chairmanship of Justice S.K.Dar, for forming linguistic provinces. On 10 December 1948, the report of Dar Commission was published but the issue remained unsolved. -

Ambedkar Times September, 2014 Layout 1

Editor-in-Chief: Prem Kumar Chumber Contact: 001-916-947-8920 Fax: 916-238-1393 E-mail: [email protected] Editors: Takshila & Kabir Chumber VOL- 6 ISSUE- 12-13 September, 2014 www.ambedkartimes.com www.ambedkartimes.org Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, Poona Pact and the Current Situation Efforts to purchase Dr Ambedkar former Prem K. Chumber (Editor-in Chief) www.ambedkartimes.com Residence in London for an Ambedkar Memorial Babasaheb Dr. B. R. Ambedkar devoted his entire life pounds to purchase the property. proposed memorial will be a cul- for the emancipation and empowerment of the London (Ambedkar Times "I am delighted that the Govern- tural and educational centre that Scheduled Castes of India who for centuries have News Bureau)- Efforts are being ment of Maharashtra has sup- generations of Indians in the UK been compelled to live in deplorable situations. He made to convert the former Lon- ported the FABO, UK's initiative and visitors interested or inspired tried different ways for this noble cause while set- don residence of Dr B.R. Ambed- to purchase the house where Dr by Dr Ambedkar’s key roles in ting the goal of annihilation of caste. First, he did kar into an Ambedkar memorial. Ambedkar lodged while he was furthering social justice, human his best to improve upon the situations through re- He lived at 10 King Henrys Road studying at the London School of rights and equal treatment issues forms within Hinduism. But soon, he realized that London in 1921-22 during his can visit. The bedrooms would reforms within Hinduism will not work for the anni- higher studies in the London be ideal for some students from hilation of caste because without caste the whole School of Economics. -

![4H4 TR]] ` 22A Ezvd E`Urj](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7086/4h4-tr-22a-ezvd-e-urj-877086.webp)

4H4 TR]] ` 22A Ezvd E`Urj

C M Y K RNI Regn. No. MPENG/2004/13703, Regd. No. L-2/BPLON/41/2006-2008 O O !"! #"$%& '('('!" )* " some of the comments and people from different sections Former Chief Ministers barbs by party’s senior leaders of society and held several Siddharamaiah, Oomen he Congress Working gave opportunities to ruling rounds of consultations with Chandy, Tarun Gogoi and TCommittee (CWC) on parties to embarrass the them across the country, to Harish Rawat will attend the Monday is likely to take the Congress. The Congress lead- include their views in the man- meeting. Priyanka Gandhi final call on AAP-Congress ers will discuss pros and cons of ifesto. It has also launched an Vadra and Jyotiraditya Scindia, alliance in the national Capital aligning with the AAP. While online portal to seek views and who took charge last month as and also strategise on how to the opinion within the expectations of people from AICC general secretary UP run the party’s campaigns in Congress is divided on this the grand old party ahead of east and UP west respectively, Opposition-ruled States like issue, NCP Chief Sharad Pawar the Lok Sabha polls. The top will also be present. West Bengal, Andhra Pradesh is actively involved in getting party leaders have promised to The party also released its without annoying its prospec- the two parties together. make the manifesto a com- ninth list of 10 candidates for tive post-poll allies. The issue has divided prehensive document that will the Lok Sabha elections, field- Sources said the Congress Delhi Congress unit between include views of all sections. -

GI Journal No. 134 1 April 28, 2020

GI Journal No. 134 1 April 28, 2020 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS JOURNAL NO. 134 APRIL 28, 2020 / VAISAKHA 10, SAKA 1942 GI Journal No. 134 2 April 28, 2020 INDEX S. No. Particulars Page No. 1 Official Notices 4 2 New G.I Application Details 5 3 Public Notice 7 4 GI Authorised User Applications Mysore Rosewood Inlay- GI Application No. 46 8 Temple Jewellery of Nagercoil - GI Application No. – 65 & 515 21 Lucknow Chikan Craft - GI Application No. 119 22 Alphonso - GI Application No. 139 24 Surat Zari Craft - GI Application No. 171 265 Dahanu Gholvad Chikoo - GI Application No. – 493 289 Banglar Rasogolla - GI Application No. 533 290 Idu Mishmi Textiles - GI Application No. – 625 297 5 General Information 331 6 Registration Process 333 GI Journal No. 134 3 April 28, 2020 OFFICIAL NOTICES Sub: Notice is given under Rule 41(1) of Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration & Protection) Rules, 2002. 1. As per the requirement of Rule 41(1) it is informed that the issue of Journal 134 of the Geographical Indications Journal dated 28th April, 2020 / Vaisakha 10, Saka 1942 has been made available to the public from 28th April, 2020. GI Journal No. 134 4 April 28, 2020 NEW G.I APPLICATION DETAILS App.No. Geographical Indications Class Goods 650 Kumaon Chyura Oil 30 Agricultural 651 Munsyari Razma of Uttarakhand 31 Agricultural 652 Uttarakhand Ringal Craft 27 Handicraft 653 Uttarakhand Tamta Product 27 Handicraft 654 ttarakhand Thulma 27 Handicraft 655 Goan Khaje 30 Food Stuff 656 Manjusha Art 16 Handicraft 657 Tikuli Art 16 -

Annexure-V State/Circle Wise List of Post Offices Modernised/Upgraded

State/Circle wise list of Post Offices modernised/upgraded for Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) Annexure-V Sl No. State/UT Circle Office Regional Office Divisional Office Name of Operational Post Office ATMs Pin 1 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA PRAKASAM Addanki SO 523201 2 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL KURNOOL Adoni H.O 518301 3 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM AMALAPURAM Amalapuram H.O 533201 4 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Anantapur H.O 515001 5 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Machilipatnam Avanigadda H.O 521121 6 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA TENALI Bapatla H.O 522101 7 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Bhimavaram Bhimavaram H.O 534201 8 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA VIJAYAWADA Buckinghampet H.O 520002 9 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL TIRUPATI Chandragiri H.O 517101 10 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Prakasam Chirala H.O 523155 11 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CHITTOOR Chittoor H.O 517001 12 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CUDDAPAH Cuddapah H.O 516001 13 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM VISAKHAPATNAM Dabagardens S.O 530020 14 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL HINDUPUR Dharmavaram H.O 515671 15 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA ELURU Eluru H.O 534001 16 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudivada Gudivada H.O 521301 17 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudur Gudur H.O 524101 18 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Guntakal H.O 515801 19 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA -

History of Modern Maharashtra (1818-1920)

1 1 MAHARASHTRA ON – THE EVE OF BRITISH CONQUEST UNIT STRUCTURE 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Political conditions before the British conquest 1.3 Economic Conditions in Maharashtra before the British Conquest. 1.4 Social Conditions before the British Conquest. 1.5 Summary 1.6 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES : 1 To understand Political conditions before the British Conquest. 2 To know armed resistance to the British occupation. 3 To evaluate Economic conditions before British Conquest. 4 To analyse Social conditions before the British Conquest. 5 To examine Cultural conditions before the British Conquest. 1.1 INTRODUCTION : With the discovery of the Sea-routes in the 15th Century the Europeans discovered Sea route to reach the east. The Portuguese, Dutch, French and the English came to India to promote trade and commerce. The English who established the East-India Co. in 1600, gradually consolidated their hold in different parts of India. They had very capable men like Sir. Thomas Roe, Colonel Close, General Smith, Elphinstone, Grant Duff etc . The English shrewdly exploited the disunity among the Indian rulers. They were very diplomatic in their approach. Due to their far sighted policies, the English were able to expand and consolidate their rule in Maharashtra. 2 The Company’s government had trapped most of the Maratha rulers in Subsidiary Alliances and fought three important wars with Marathas over a period of 43 years (1775 -1818). 1.2 POLITICAL CONDITIONS BEFORE THE BRITISH CONQUEST : The Company’s Directors sent Lord Wellesley as the Governor- General of the Company’s territories in India, in 1798. -

Imagereal Capture

H.M. SEERVAI - HIS LIFE, BOOK & LEGACY Michael Kirbylt LIFE The common law system, followed in most countries that at one stage in their history were part of the British Empire, is as dependent for its success upon leading advocates and fine scholars as it is on great judges. In India, one such advocate and scholar, of world renown, was Hormasji Maneckji Seervai, born in Bombay on 5 December 1906. Seetvai, as every Indian lawyer knows, was the author of the great commentary, Constitutional Law of India. But first and foremost, he was a brilliant advocate who won spectacular success before the Supreme Court of India and other courts. It is a privilege for me to offer these reflections on Seervai, whose centenary was celebrated in 2006. My remarks are based on a lecture that I delivered at the Bombay High Court in January 2007, the penultimate year ofmyjudiCial service in Australia, as a member ofthe High Court ofAustralia, the nation's apex court. I approach my task with a great love of India, a respect for its Bench and Bar and an admiration for my subject. I spoke of Seervai, of his life, of his work and of his legacy. Most advocates and judges, however great, walk for but a short hour on the stage of the law. They play their parts. Their voices are raised and the pages of the books are filled with their learning. But then they depart. They are remembered by their loved ones and a few friends or grateful litigants. But soon they are forgotten.