Imagereal Capture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Modern Maharashtra (1818-1920)

1 1 MAHARASHTRA ON – THE EVE OF BRITISH CONQUEST UNIT STRUCTURE 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Political conditions before the British conquest 1.3 Economic Conditions in Maharashtra before the British Conquest. 1.4 Social Conditions before the British Conquest. 1.5 Summary 1.6 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES : 1 To understand Political conditions before the British Conquest. 2 To know armed resistance to the British occupation. 3 To evaluate Economic conditions before British Conquest. 4 To analyse Social conditions before the British Conquest. 5 To examine Cultural conditions before the British Conquest. 1.1 INTRODUCTION : With the discovery of the Sea-routes in the 15th Century the Europeans discovered Sea route to reach the east. The Portuguese, Dutch, French and the English came to India to promote trade and commerce. The English who established the East-India Co. in 1600, gradually consolidated their hold in different parts of India. They had very capable men like Sir. Thomas Roe, Colonel Close, General Smith, Elphinstone, Grant Duff etc . The English shrewdly exploited the disunity among the Indian rulers. They were very diplomatic in their approach. Due to their far sighted policies, the English were able to expand and consolidate their rule in Maharashtra. 2 The Company’s government had trapped most of the Maratha rulers in Subsidiary Alliances and fought three important wars with Marathas over a period of 43 years (1775 -1818). 1.2 POLITICAL CONDITIONS BEFORE THE BRITISH CONQUEST : The Company’s Directors sent Lord Wellesley as the Governor- General of the Company’s territories in India, in 1798. -

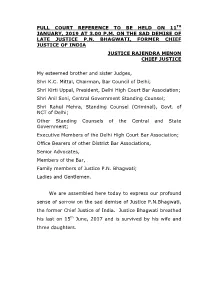

Full Court Reference to Be Held on 11Th January, 2019 at 3.00 P.M

FULL COURT REFERENCE TO BE HELD ON 11TH JANUARY, 2019 AT 3.00 P.M. ON THE SAD DEMISE OF LATE JUSTICE P.N. BHAGWATI, FORMER CHIEF JUSTICE OF INDIA JUSTICE RAJENDRA MENON CHIEF JUSTICE My esteemed brother and sister Judges, Shri K.C. Mittal, Chairman, Bar Council of Delhi; Shri Kirti Uppal, President, Delhi High Court Bar Association; Shri Anil Soni, Central Government Standing Counsel; Shri Rahul Mehra, Standing Counsel (Criminal), Govt. of NCT of Delhi; Other Standing Counsels of the Central and State Government; Executive Members of the Delhi High Court Bar Association; Office Bearers of other District Bar Associations, Senior Advocates, Members of the Bar, Family members of Justice P.N. Bhagwati; Ladies and Gentlemen. We are assembled here today to express our profound sense of sorrow on the sad demise of Justice P.N.Bhagwati, the former Chief Justice of India. Justice Bhagwati breathed his last on 15th June, 2017 and is survived by his wife and three daughters. Justice Bhagwati was born on 21st December 1921 at Ahmadabad, then in Bombay Presidency, in a family of Judges and lawyers. His father has been a judge of the Supreme Court of India. He completed his education from Bombay. He studied at Elphinstone College and received a degree in Mathematics (Hons.) from the University of Bombay in 1941 with distinction. Thereafter he graduated in law from Bombay University, as a student of Government Law College, Bombay in the year 1945. During his college life, he had also participated in the freedom movement. He was deeply associated with the Quit India Movement of 1942. -

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar and the Downtrodden

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 4 Issue 11 || November. 2015 || PP.55-59 DR. B.R. AMBEDKAR AND THE DOWNTRODDEN Dr. Mrs. ManjeetHundal Head, Sociology Department, S.R.C.S.D. College, Pathankot Abstract: Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar popularly known as Babasaheb was an Indian jurist, economist, politician and social reformer who inspired the modern Buddhist movement and campaigned against social discrimination of dalits, women and labour. Dr.Ambedkar struggled throughout from 1920-1940 on the questionof „How to emancipate untouchables from the ritual system known as Hinduism and how to create a society based on the values of liberty, equality and fraternity‟.This paper tries to give answer to these questions by explaining caste, life history of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar and his struggle for equality. I. CASTE The caste system in India is a system of social stratification which historically separates communities into thousands of endogamous hereditary groups called Jatis usually translated into English as castes. Caste is taken from Portugese word Casta which means birth, so caste is a group, the membership of which is based on birth. According to Sir Herbert Risley, “Caste is a collection of families, a group of families bearing a common name, claiming a common descent from mythical ancestor, human or divine, professing to follow the same hereditary call and regarded by those who are competent to give an opinion as forming a single homogeneous -

Draf El-Roll-Principal.Pdf

id13650906 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com 1 UNIVERSITY OF MUMBAI U niversity Election Top priority Email- [email protected] Tel.No. - 022-2270 8710 022-2269 6147 No. EL/ Senate (25)(2)(l) & A.C. (29)(2)(f)/ 42 B of 2010. 15th July, 2010. Sub. : Election to the Senate from the Principals of the Affiliated /Autonomous/ Conducted/ colleges Under Section 25(2)(l) and to the Academic Council Under Section 29(2) (f) of the Maharashtra Universities Act, 1994: Ref.: 1. Circular/Notification No. EL/ Senate25 (2) (l) & A.C. 29(2) nd (f)/ 42 of 2010, dated 2 March, 2010 2. Circular/Notification No. EL/ Senate-25(2) (l) & A.C. 29(2) th (f)/42-A of 2010 dated 13 April, 2010 Mesdames/Gentlemen, Attention of the Principals of all the Affiliated /Autonomous /Conducted Colleges is invited to the above mentioned University Circular/Notification according to which they were requested to furnish the required information of the Principals for preparation of the Electoral Roll for the purpose of holding the elections of Senate and Academic Council. The information submitted by the Principals has been scrutinized and the Draft Electoral Roll of the Principals of the affiliated/ conducted/ autonomous colleges is being published in three parts. (i.e. Part I, Part II and Part III). The concerned Principals are requested to go through the Draft Electoral Roll and th ‘ ’ submit their objections if any, on or before, 26 July, 2010 in the format (Appendix A ), with the supporting documents, failing which it will be presumed that there is no objection to the Draft and the same Draft will be published as final Electoral Roll. -

Appendix by Avani Bansal.Pdf

AGE TENURE IN WHILE PREVIOUS LEGAL DIFFERENTLY NAME STATE RELIGION GENDER EDUCATION STATUS SC AS CJI MOVING POSITION LEGACY ABLED TO SC Associate Judge of the 26th January Federal Court 1950 – 6th LLB & LLM from (then was H.J. KANIA November Gujarat 60 yrs. Hindu Male None No Government Law appointed as 1951 (1 year, College, Bombay the first CJ in 284 days) Supreme Court) Third in 7 November seniority in 1951 - 3 B.A and LLB from M. Patanjali Madras High January 1954 Madras 62 yrs. Hindu Male None No Madras University in Sastri Court, later, (2 years, 1912 Judge of the 57 days) Federal Court 4 January Prime 1954 - 22 Father LL. B degree from Mehr Chand Himachal Minister of December 65 yrs. Hindu Male (Advocate No Government Mahajan Pradesh Jammu & 1954 Lala Brij Lal) College, Lahore Kashmir (352 days) 23 Judge in December M.A.(History), B.L. Supreme Bijan Kumar 1954 – 31 (Gold Medalist), Calcutta 63 yrs. Hindu Male Court 14 Oct. None No Mukherjea January 1956 M.L.(Gold Medalist), 1948-22 (1 year, Doctor of Law Dec.1954. 39 days) 1 February Chief Justice 1956 – 30 of Punjab September L.L.B from University Sudhi Ranjan Das Calcutta 62 yrs. Hindu Male High Court None No 1959 College, London from 1949 to (3 years, 1950. 241 days) 1 October B.A. (Hons.) and 1959 – 31 Chief Justice Bhuvaneshwar M.A. Examinations January 1964 Bihar 60 yrs. Hindu Male of Bombay None No Prasad Sinha of the Patna (4 years, High Court University 122 days) 1 February M.A. -

Bombay 100 Years Ago, Through the Eyes of Their Forefathers

Erstwhile, ‘Bombay’, 100 years ago was beautifully built by the British where the charm of its imagery and landscape was known to baffle all. The look and feel of the city was exclusively reserved for those who lived in that era and those who used to breathe an unassuming air which culminated to form the quintessential ‘old world charisma’. World Luxury Council (India) is showcasing, ‘never seen before’ Collectors’ Edition of 100 year old archival prints on canvas through a Vintage Art Exhibit. The beauty of the archival prints is that they are created with special ink which lasts for 100 years, thus not allowing the colors to fade. The idea is to elicit an unexplored era through paradoxically beautiful images of today’s maximum city and present it to an audience who would have only envisioned Bombay 100 years ago, through the eyes of their forefathers. The splendid collection would be an absolute treat for people to witness and make part of their ‘vintage art’ memorabilia. World Luxury Council India Headquartered in London, UK, World Luxury Council (India) is a ‘by invitation only’ organization which endeavours to provide strategic business opportunities and lifestyle management services though its 4 business verticals – World Luxury Council, World Luxury Club, Worldluxurylaunch.com and a publishing department for luxury magazines. This auxiliary marketing arm essentially caters to discerning corporate clients and high net worth individuals from the country and abroad. The Council works towards providing knowledge, assistance and advice to universal luxury brands, products and services requiring first class representation in Indian markets through a marketing mix of bespoke events, consultancy, web based promotions, distribution and networking platforms. -

A Small Biography of Alshashtri Jambhekar

A Small Biography of R.M. Khaladkar 17/5, Shindenagar, Bavdhan (Khurd), Alshashtri Jambhekar NDA Road, Pune – The First Indian who Headed E-mail: [email protected] the Colaba Observatory The Colaba observatory was established by the below in order that it would provide information and East India Company in 1826 for astronomical inspiration to many of our colleagues of the present observations and time keeping services for and the coming generations. Bombay (Mumbai) port. The geomagnetism and meteorological measurements started in 1841 Early life th by Prof. Orlebar who was then the Professor of He was born on 6 January 1812 in a remote natural philosophy (science) at the Elphinstone village- Pombhurle in Sindhudurg district of Konkan college. However, in 1842 he had to go on the region, Maharashtra. After primary education in medical leave for two years. During this period, Marathi and Sanskrit, he shifted to Mumbai at age one Indian luminary - Balshashtri Jambhekar (BJ) 13. There, he excelled in many fields as fast as it was appointed as the Head of this observatory. was almost impossible for any other person, Considering the fact that at that time, most of the especially when the educational institutions, means top positions in India were occupied by the of knowledge like books, newspapers were not Britishers, exceptionally a great honour was available in India as they are today. bestowed upon this young Indian at an age of just Subjects and languages mastered by BJ 31 years. Undoubtedly, it was because of his When most of the population of India was proven merits in the scientific field. -

Prospectus 2014-15

Government of Maharashtra 156, M.G. ROAD, FORT, MUMBAI - 32. PROSPECTUS 2014-15 Tel.: (022) 2284 4060, 2284 3797 www.elphinstone.ac.in 1 CONTENTS 1. Introduction 3 2. A Brief History 3 3. Vision, Mission & Goals of the Institution 4 4. The Road ahead 5 5. Courses offered 6 6. Fee structure 15 7. Rules for Admission 20 8. Rules for maintaining discipline in the college 22 9. Facilities for students support 23 10. Extra Curricular & Co- Curricular activities. 25 11 Hostel facility 25 12. College Library 26 13. Fellowships & Scholarships 26 14. Some distinguished Alumni 31 15. List of Principals of the College 32 2 1. INTRODUCTION Elphinstone College occupies a unique position in the annals of education in the country. It is an outstanding place of learning which came into existence much before the University of Mumbai, to which it was later on affiliated. The institution is known for its open access to students from all strata of the society. This includes various communities, income groups and interests. It is one of the few colleges in Mumbai with an extensive hostel facility for both boys and girls. Located within a walking range from the college and overlooking the Marine Drive, the hostel is certainly among the unique strengths of the College. The college has an enviable location, which is also historically significant. The building of the College with its gothic architecture, has been classified as a Grade I Heritage structure. It has recently been restored by the Kala Ghoda Association and has regained its luminous look. It stands out like a pearl as night falls. -

B. R. Ambedkar

B. R. Ambedkar Contents Bhimrao Ramji (B R) Ambedkar’s profile ................................................................. 3 Writings and speeches ............................................................................................. 11 Criticism and legacy ................................................................................................ 12 BOOKS/DOCUMENTS .......................................................................................... 13 Page 2 of 34 Bhimrao Ramji (B R) Ambedkar’s profile (From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia) Born 14 April 1891, at Mhow, Central Provinces, British India (now in Madhya Pradesh). Passed away on 6th December 1956 (aged 65) Delhi, India. Nationality, Indian. Other names Baba, Baba Saheb, Bodhisatva, Bhima, Mooknayak, Adhunik Buddha. Alma mater University of Mumbai, Columbia University, University of London, London School of Economics Organization: Samata Sainik Dal, Independent Labour Party, Scheduled Castes Federation.1st Law Minister of India, Chairman of the Constitution Drafting Committee. Religion: Buddhism.Spouse Ramabai Ambedkar (married 1906) Savita Ambedkar (married 1948). Awards: Bharat Ratna (1990) Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (14 April 1891-6th December 1956), also known as Babasaheb, was an Indian jurist, political leader, philosopher, thinker, anthropologist, historian, orator, prolific writer, economist, scholar, editor, and a revolutionary. He was also the Chairman of the Drafting Committee of Indian Constitution. Born into a poor Mahar (considered an Untouchable -

Mahatma Gandhi As a Student

Mahatma Gandhi as a student Compiled and Edited by: J. M. Upadhyaya Published by: The Director Publications Division Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Government of India, Patiala House New Delhi 110 001, India. © Publication Division Mahatma Gandhi as a student FOREWORD So much has already been said about Mahatma Gandhi and yet there remains so much more to be said about him. The Mahatma’s life and work were all embracing; there was not an activity of our national or social life which remained untouched by him. Whilst we have a number of books which give adequate accounts of Gandhiji’s social and political work, I think there is little information about his childhood and early youth. After all the Mahatma that Gandhi became in later life was a child like many other children and it is interesting to find out what environment and influences were responsible for moulding him. It is from this point of view that I read the page proofs of this book. The author seems to have taken great pains and I do hope his book will be widely read and appreciated. Zakin Hussain New Delhi January 15, 1965 www.mkgandhi.org Page 2 Mahatma Gandhi as a student INTRODUCTORY Gandhiji, it has been well said, could fashion heroes out of common clay. His first and, undoubtedly, his most successful experiment was with himself. This booklet is a modest, attempt to present a detailed and documented account of the student career of Gandhiji who set himself down as "a mediocre student". It covers the period of his childhood, adolescence and early youth and is based on authentic records. -

Elphinstone College

Registration Form ICSSR Sponsored National Workshop on „„Quantitative Research Analysis in Social Sciences” organized by Department of Sociology Government of Maharashtra‟s Name of the Participant: __________________ Designation: ____________________________ Elphinstone College Name and Address of the College: _________ 156, M.G. ROAD, FORT, MUMBAI - 32. (Reaccredited „A‟ Grade by NAAC) ——————————————————— ———————————————————- Contact No: ___________________________ Email-id of the Participant: ______________ ——————————— ICSSR Sponsored National Workshop Registration Fee: Cash/DD/ per participant ( payable at Mumbai) in Favour of “Principal , On Elphinstone College” „„Quantitative Research Analysis in Social Sciences” organized Signature of the Participant_______________ by Signature of the Principal _________________ Department of Sociology DD no._______________, Drawn on_____________________________ Branch____________________________ Cash_____________________________ Kindly confirm your registrations by 10th January 2018. 20th January 2018 About the College A good knowledge of quantitative data Program Schedule: Elphinstone College is one of the premier analysis is essential for progress in academic and 10:00-11:00 Inauguration & Keynote Address: institutions in the field of higher education in the corporate World. Prof. Dr. B. V. Bhosale, country. The list of alumni nurtured by the Col- It facilitates management of a wide Professor & Head, Department of lege testifies the commitment of the College to- range of data with varying attributes following es- Sociology, Mumbai University, Mumbai. wards excellence in the field of higher education. tablished procedures. The knowledge of SPSS can 11:00– 01:00 Dr. Manasi Bawdekar, Co-ordinator, Research Unit, Nirmala Over the past 161 years, Elphinstone College has offer a professional edge which critical to the find- Niketan MSW college, Mumbai established itself as an institution of learning to ings of Qualitative s well as Quantitative research 1:00-2:00 Lunch reckon with, both within and outside country. -

ELPHINSTONE COLLEGE a Two-Day Webinar Introduction to Research Designs from Theory to Practice

Government of Maharashtra’s About the college ELPHINSTONE COLLEGE Mumbai – 400 032 Elphinstone College is a premier institute of higher education in India. Established in 1856, NAAC Reaccredited ‘A’ Grade prior to the establishment of Mumbai University, the college has played a pivotal role in laying the foundations of a modern India through its illustrious alumni. It is now a constituent college of the first Cluster University in Maharashtra, the Dr. Homi Bhabha State University, Mumbai. It is committed to nation building by providing quality education to all sections of society. INTERNAL QUALITY ASSURANCE CELL AND DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHOLOGY An enviable location, well equipped library, smart classrooms, computer laboratories, gymkhana, and a host of facilities enrich the learning experience. The college offers degree Present courses in Arts, Science, Commerce, Biotechnology, and Information Technology. The interest of the students has always been at the heart of dedicated teachers, who are eminent A Two-Day Webinar personalities in their area of expertise. on Introduction to Research Designs ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ From Theory to Practice Facilitator: Resource Person Shivanand Thorat Shivanand Thorat Masters in Industrial Psychology, NET, SET; He is currently working as a visiting faculty 29th & 30th April 2020 at Symbiosis College of Arts and Commerce, Pune; working as a data analyst and research 12.00 p.m. to 1.00 p.m. assistant on CSSH research