Avoid a Staccato Speech Rhythm a Thesis the Centre for Teaching

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Dynamic Markings

Basic Dynamic Markings • ppp pianississimo "very, very soft" • pp pianissimo "very soft" • p piano "soft" • mp mezzo-piano "moderately soft" • mf mezzo-forte "moderately loud" • f forte "loud" • ff fortissimo "very loud" • fff fortississimo "very, very loud" • sfz sforzando “fierce accent” • < crescendo “becoming louder” • > diminuendo “becoming softer” Basic Anticipation Markings Staccato This indicates the musician should play the note shorter than notated, usually half the value, the rest of the metric value is then silent. Staccato marks may appear on notes of any value, shortening their performed duration without speeding the music itself. Spiccato Indicates a longer silence after the note (as described above), making the note very short. Usually applied to quarter notes or shorter. (In the past, this marking’s meaning was more ambiguous: it sometimes was used interchangeably with staccato, and sometimes indicated an accent and not staccato. These usages are now almost defunct, but still appear in some scores.) In string instruments this indicates a bowing technique in which the bow bounces lightly upon the string. Accent Play the note louder, or with a harder attack than surrounding unaccented notes. May appear on notes of any duration. Tenuto This symbol indicates play the note at its full value, or slightly longer. It can also indicate a slight dynamic emphasis or be combined with a staccato dot to indicate a slight detachment. Marcato Play the note somewhat louder or more forcefully than a note with a regular accent mark (open horizontal wedge). In organ notation, this means play a pedal note with the toe. Above the note, use the right foot; below the note, use the left foot. -

Articulation from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Articulation From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Examples of Articulations: staccato, staccatissimo,martellato, marcato, tenuto. In music, articulation refers to the musical performance technique that affects the transition or continuity on a single note, or between multiple notes or sounds. Types of articulations There are many types of articulation, each with a different effect on how the note is played. In music notation articulation marks include the slur, phrase mark, staccato, staccatissimo, accent, sforzando, rinforzando, and legato. A different symbol, placed above or below the note (depending on its position on the staff), represents each articulation. Tenuto Hold the note in question its full length (or longer, with slight rubato), or play the note slightly louder. Marcato Indicates a short note, long chord, or medium passage to be played louder or more forcefully than surrounding music. Staccato Signifies a note of shortened duration Legato Indicates musical notes are to be played or sung smoothly and connected. Martelato Hammered or strongly marked Compound articulations[edit] Occasionally, articulations can be combined to create stylistically or technically correct sounds. For example, when staccato marks are combined with a slur, the result is portato, also known as articulated legato. Tenuto markings under a slur are called (for bowed strings) hook bows. This name is also less commonly applied to staccato or martellato (martelé) markings. Apagados (from the Spanish verb apagar, "to mute") refers to notes that are played dampened or "muted," without sustain. The term is written above or below the notes with a dotted or dashed line drawn to the end of the group of notes that are to be played dampened. -

Music Is Made up of Many Different Things Called Elements. They Are the “I Feel Like My Kind Building Bricks of Music

SECONDARY/KEY STAGE 3 MUSIC – BUILDING BRICKS 5 MINUTES READING #1 Music is made up of many different things called elements. They are the “I feel like my kind building bricks of music. When you compose a piece of music, you use the of music is a big pot elements of music to build it, just like a builder uses bricks to build a house. If of different spices. the piece of music is to sound right, then you have to use the elements of It’s a soup with all kinds of ingredients music correctly. in it.” - Abigail Washburn What are the Elements of Music? PITCH means the highness or lowness of the sound. Some pieces need high sounds and some need low, deep sounds. Some have sounds that are in the middle. Most pieces use a mixture of pitches. TEMPO means the fastness or slowness of the music. Sometimes this is called the speed or pace of the music. A piece might be at a moderate tempo, or even change its tempo part-way through. DYNAMICS means the loudness or softness of the music. Sometimes this is called the volume. Music often changes volume gradually, and goes from loud to soft or soft to loud. Questions to think about: 1. Think about your DURATION means the length of each sound. Some sounds or notes are long, favourite piece of some are short. Sometimes composers combine long sounds with short music – it could be a song or a piece of sounds to get a good effect. instrumental music. How have the TEXTURE – if all the instruments are playing at once, the texture is thick. -

Download File

NAVIGATING MUSICAL PERIODICITIES: MODES OF PERCEPTION AND TYPES OF TEMPORAL KNOWLEDGE Galen Philip DeGraf Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Galen Philip DeGraf All rights reserved ABSTRACT Navigating Musical Periodicities: Modes of Perception and Types of Temporal Knowledge Galen Philip DeGraf This dissertation explores multi-modal, symbolic, and embodied strategies for navigating musical periodicity, or “meter.” In the first half, I argue that these resources and techniques are often marginalized or sidelined in music theory and psychology on the basis of definition or context, regardless of usefulness. In the second half, I explore how expanded notions of metric experience can enrich musical analysis. I then relate them to existing approaches in music pedagogy. Music theory and music psychology commonly assume experience to be perceptual, music to be a sound object, and perception of music to mean listening. In addition, observable actions of a metaphorical “body” (and, similarly, performers’ perspectives) are often subordinate to internal processes of a metaphorical “mind” (and listeners’ experiences). These general preferences, priorities, and contextual norms have culminated in a model of “attentional entrainment” for meter perception, emerging through work by Mari Riess Jones, Robert Gjerdingen, and Justin London, and drawing upon laboratory experiments in which listeners interact with a novel sound stimulus. I hold that this starting point reflects a desire to focus upon essential and universal aspects of experience, at the expense of other useful resources and strategies (e.g. extensive practice with a particular piece, abstract ideas of what will occur, symbolic cues) Opening discussion of musical periodicity without these restrictions acknowledges experiences beyond attending, beyond listening, and perhaps beyond perceiving. -

Choir 6 Grade

Choir 6th Grade Jessica Arnold, Northwest Middle School Vicki Mount, North Middle School Amy Smick, East/Southeast Middle School Matt McClellan – Special Areas Curriculum Coordinator Reviewed by Curriculum Advisory Committee on October 9, 2014 Presented to the Board of Education on December 16, 2014 COURSE TITLE: Choir 6 GRADE LEVEL: 6th CONTENT AREA: Fine Arts Course Description: Students will study vocal techniques, ensemble skills, and basic music theory as related to appropriate music level. Performances are mandatory at the discretion of the teacher. Course Rationale: 6th Grade Choir serves as an introduction to vocal music. Students will develop basic vocal techniques while incorporating the higher order thinking skills of analysis, synthesis, and evaluation in order to have a meaningful musical experience. Course Scope and Sequence Unit 1: Rehearsal and Unit 2: Rhythm Notation and Unit 3: Pitch Notation and Performance Technique Reading Reading (ongoing) (12 weeks) (12 weeks) Unit 4: Road Maps of Unit 5: Dynamics Music/Signs and Symbols (4 weeks) (4 weeks) Unit Objectives: Unit 1: Rehearsals and Performance Technique 1. Students will know the importance of warming up prior to singing. 2. Students will apply techniques to create a quality singing tone. 3. Students will apply the concept of balance and blend across a choral ensemble. 4. Students will sing 2‐part music in the choral setting. 5. Students will sing using the appropriate expression for the context of the selected piece. 6. Students will display appropriate concert etiquette on stage and in the audience. Unit 2: Rhythm Notation and Reading 1. Students will know basic vocabulary regarding rhythmic notation, including staff, time signature, barline, measure, and double barline. -

Dynamics, Articulations, Slurs, Tempo Markings

24 LearnMusicTheory.net High-Yield Music Theory, Vol. 1: Music Theory Fundamentals Section 1.9 D YNAMICS , A RTICULATIONS , S LURS , T E M P O M ARKINGS Dynamics Dynamics are used to indicate relative loudness: ppp = pianississimo = very, very soft pp = pianissimo = very soft = piano = soft p mp = mezzo-piano = medium-soft mf = mezzo-forte = medium-loud f = forte = loud ff = fortissimo = very loud fff = fortississimo = very, very loud fp = forte followed suddenly by piano; also mfp, ffp, etc. sfz = sforzando = a forceful, sudden accent fz is forceful but not as sudden as sfz Articulations Articulations specify how notes should be performed, either in terms of duration or stress. Staccatissimo means extremely shortened duration. Staccato means shortened duration. Tenuto has two functions: it can mean full duration OR a slight stress or emphasis. Accent means stressed or emphasized (more than tenuto). Marcato means extremely stressed. An articulation of duration (staccatissimo, staccato, or tenuto) may combine with one of stress (tenuto, accent, or marcato). articulations of duration œÆ œ. œ- >œ œ^ & staccatto tenuto accent marcato staccattisimo articulations of stress Slurs Slurs are curved lines connecting different pitches. Slurs can mean: (1.) Bowings connect the notes as a phrase; (2.) for string instruments: play with one motion of the bow (up or down); (3.) for voice: sing with one syllable, or (4.) for wind instruments: don’t tongue between the notes. ? b2 œ œ œ œ ˙ b 4 Chapter 1: Music Notation 25 Fermatas Fermatas indicate that the music stops and holds the note until the conductor or soloist moves on. -

Musical Symbols Range: 1D100–1D1FF

Musical Symbols Range: 1D100–1D1FF This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

The Art of Marimba Articulation: a Guide for Composers, Conductors, And

THE ART OF MARIMBA ARTICULATION: A GUIDE FOR COMPOSERS, CONDUCTORS, AND PERFORMERS ON THE EXPRESSIVE CAPABILITIES OF THE MARIMBA Adam B. Davis, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2018 APPROVED: Mark Ford, Major Professor Eugene Corporon, Committee Member Christopher Deane, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies Musicin the College of Music John W. Richmond, Dean of the College of Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School The Art of Marimba Articulation: A Guide for Composers, Conductors, and PerformersDavis, Adam on the B. Expressive Capabilities of the Marimba 233 6 . Doctor of Musical82 titles. Arts (Performance), August 2018, pp., tables, 49 figures, bibliography, Articulation is an element of musical performance that affects the attack, sustain, and the decay of each sound. Musical articulation facilitates the degree of clarity between successive notes and it is one of the most important elements of musical expression. Many believe that the expressive capabilities of percussion instruments, when it comes to musical articulation, are limited. Because the characteristic attack for most percussion instruments is sharp and clear, followed by a quick decay, the common misconception is that percussionists have little or no control over articulation. While the ability of percussionists to affect the sustain and decay of a sound is by all accounts limited, the virtuability of percussionists to change the attack of a sound with different implements is ally limitless. In addition, where percussion articulation is limited, there are many techniques that allow performers to match articulation with other instruments. -

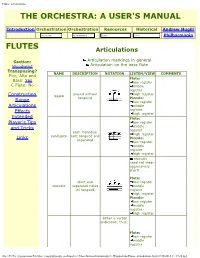

Flutes: Articulations the ORCHESTRA: a USER's MANUAL

Flutes: articulations THE ORCHESTRA: A USER'S MANUAL Introduction Orchestration Orchestration Resources Historical Andrew Hugill by section by instrument select... select... Philharmonia FLUTES Articulations Section: Articulation markings in general Woodwind Articulation on the bass flute Transposing? NAME DESCRIPTION NOTATION LISTEN/VIEW COMMENTS Picc, Alto and Flute: Bass: Yes low register C Flute: No middle register played without high register Construction legato tonguing Piccolo: Range low register Articulations middle Effects register high register Extended Flute: Player's Tips low register middle and Tricks register each individual high register nonlegato note tongued and Links Piccolo: separated low register middle register high register staccato need not mean aggressively short! Flute: short and low register staccato separated notes middle (all tongued) register high register Piccolo: low register middle register high register Either a verbal indication, thus: Flute: low register middle register file:///E|/Τα έγγραφά μου/Τσέτσος, ενορχήστρωση (μαθήματα)+/Enorchistrosi Instruments/3. Woodwinds/Flutes articulations.htm[17/10/2015 11:17:28 πμ] Flutes: articulations high register very short notes staccatissimo Piccolo: (tongued) or 'wedge' low register notation, as middle follows: register high register tongued slurring interpretation depending on context Players interpret tongued slurred Flute: these symbols in (no specific notes, in low register different ways. name) between legato middle Watch the video and nonlegato register clips for a brief high register explanation. Piccolo: low register middle register high register This is often called 'tenuto': Flute: low register middle register high register variation on Here's another 'tenuto' Piccolo: nonlegato common low register variation of middle nonlegato: register high register double tonguing Flute: low register middle register double tonguing high register Piccolo: low register file:///E|/Τα έγγραφά μου/Τσέτσος, ενορχήστρωση (μαθήματα)+/Enorchistrosi Instruments/3. -

Guide to Ornamentation Notation

A GUIDE TO GREY LARSEN'S NOTATION SYSTEM FOR IRISH ORNAMENTATION Over a number of years, I have developed a system of understanding and notating Irish flute and tin whistle ornamentation. This system is also applicable to the traditions of other Irish melody instruments, with some adaptations. In my books I use this system to notate ornamentation. Since it may be unfamiliar to you, I have written this guide to explain the system. Feel free to download this document and share it with other people. It is copyrighted, however, so please credit your use of this material. In addition to the most commonly used ornaments – cuts, strikes, slides, rolls, and cranns – there are double-cut rolls, and a variety of what I call condensed rolls and cranns. To learn about ornamentation in its full depth, I refer you to my book The Essential Guide to Irish Flute and Tin Whistle. WHAT IS ORNAMENTATION? When I speak of ornamentation in traditional Irish instrumental music I am referring to ways of altering or embellishing small pieces or cells of a melody that are between one and three eighth-note beats long. These alterations and embellishments are created mainly through the use of special fingered articulations (cuts and strikes) and inflections (slides), not through the addition of extra, ornamental notes. The modern classical musician’s view of ornamentation is quite different. Ornamentation, A Question & Answer Manual, a book written to help classical musicians understand ornamentation from the baroque era through the present, offers this definition: “Ornamentation is the practice of adding notes to a melody to allow music to be more expressive.”1 Classical musicians naturally tend to carry this kind of thinking with them as newcomers to traditional Irish music. -

The Controversy Over Bach's Trills: Towards a Reconciliation

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text diret.'tly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. .AJso, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing tJ. this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. U·M·I University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell tnformat1on Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. M148106-1346 USA 3131761-4700 800:521-0600 Order Number 9502692 The controversy over Bach's trills: Towards a reconciliation Polevoi, Randall Mark, D.M.A. The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 1994 U·M·I 300 N. -

How Loud,? How Sofr? I

6s UNn 4 More Musical Symbols and Terms How Loud,? How Sofr? I \fle have learned that notes tell music readers how high or low to sing or play a musical sound, and how long or short to sing or play a musical sound. There is one more thing we need to know when we sing or play music: how loud or soft to sing or play it. I Musical symbols known dyo"rr.ics tell us how loud or soft to p.rfoi- \ "r -,rri.. The dynamic symbol for loud is called forte (FOR-tay), and looks like the letter f f I The dynamic symbol for soft is called piano (Pe-AH-no, the T i same as the musical instrument) and looks like the letter p. p I The dynamic s;'mbol for very loud is two forte symbols. - I This is called fortissimo (for-TEE-see-mo). tr t r- The dynamic symbol for very soft is two piano symbols. I This is called pianissimo (pe-ah-NEE-see-mo). pp L There are dynamic sym.bols for medium loud and medium I I soft, too. For medium loud, an "m" is placed in front of the forte symbol. The "m" stands for mezzo (MET:tzo), an Italian *f r- word meaning medium or moderately. So the symbol is called I : meziLo forte (MET-tzo FOR-tay) I The symbol for medium soft is mezzo piano (MET-tzo pe-AH-no). ry I The words for the dynamiq symbols are all Italian. Now you know - five Italian words: forte (loud), piano (soft), fortissimo (very loud), L pianissimo (very soft), and mezzo (medium).