RASTAFARI TEXTS and the CREATION of PUBLICS in POST-COLONIAL JAMAICA a Thesis Submitted to the Committee on Grad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BEAR FAMILY RECORDS TEL +49(0)4748 - 82 16 16 • FAX +49(0)4748 - 82 16 20 • E-MAIL [email protected]

BEAR FAMILY RECORDS TEL +49(0)4748 - 82 16 16 • FAX +49(0)4748 - 82 16 20 • E-MAIL [email protected] ARTIST Various TITLE Calypso Craze 1956-57 And Beyond LABEL Bear Family Productions CATALOG # BCD 16947 PRICE-CODE GK EAN-CODE ÇxDTRBAMy169472z FORMAT 6-CD/1-DVD Box-Set (LP-size) with 176-page hardcover book GENRE Calypso CD 173 tracks, 484:23 min. DVD 14 chapters, ca 86 min. INFORMATION In the standard history of American pop music, the 1950s are a parade of rock icons: Bill Haley, Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, Little Richard, Elvis Presley. But after the demise of the great dance bands of the 1940s, rock 'n' roll didn't actually secure its position as the Next Big Thing until quite late in the day. For a few short months, in fact, it seemed that rock might be just another pas- sing fad – and that calypso was here to stay. From late 1956 through mid-1957, calypso was everywhere: not just on the Hit Parade, but on the dance floor and the TV, in movie theaters and magazines, in college student unions and high school glee clubs. There were calypso card games, clothing lines, and children's toys. Calypso was the stuff of commercials and comedy routines, news reports and detective novels. Nightclubs across the country hastily tacked up fishnets and palm fronds and remade themselves as calypso rooms. Singers donned straw hats and tattered trousers and affected mock-West Indian 'ahk-cents.' And it was Harry Belafonte – not Elvis Presley – who with his 1956 album 'Calypso' had the first million-selling LP in the history of the record industry. -

Afro-Jamaican Religio-Cultural Epistemology and the Decolonization of Health

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School March 2020 Mystic Medicine: Afro-Jamaican Religio-Cultural Epistemology and the Decolonization of Health Jake Wumkes University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the African Studies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Religion Commons Scholar Commons Citation Wumkes, Jake, "Mystic Medicine: Afro-Jamaican Religio-Cultural Epistemology and the Decolonization of Health" (2020). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/8311 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mystic Medicine: Afro-Jamaican Religio-Cultural Epistemology and the Decolonization of Health by Jake Wumkes A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Latin American, Caribbean, and Latino Studies Department of School of Interdisciplinary Global Studies College of Arts & Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Bernd Reiter, Ph.D. Tori Lockler, Ph.D. Omotayo Jolaosho, Ph.D. Date of Approval: February 27, 2020 Keywords: Healing, Rastafari, Coloniality, Caribbean, Holism, Collectivism Copyright © 2020, Jake Wumkes Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................... -

Pop / Rock / Commercial Music Wed, 25 Aug 2021 21:09:33 +0000 Page 1

Pop / Rock / Commercial music www.redmoonrecords.com Artist Title ID Format Label Print Catalog N° Condition Price Note 10000 MANIACS The wishing chair 19160 1xLP Elektra Warner GER 960428-1 EX/EX 10,00 € RE 10CC Look hear? 1413 1xLP Warner USA BSK3442 EX+/VG 7,75 € PRO 10CC Live and let live 6546 2xLP Mercury USA SRM28600 EX/EX 18,00 € GF-CC Phonogram 10CC Good morning judge 8602 1x7" Mercury IT 6008025 VG/VG 2,60 € \Don't squeeze me like… Phonogram 10CC Bloody tourists 8975 1xLP Polydor USA PD-1-6161 EX/EX 7,75 € GF 10CC The original soundtrack 30074 1xLP Mercury Back to EU 0600753129586 M-/M- 15,00 € RE GF 180g black 13 ENGINES A blur to me now 1291 1xCD SBK rec. Capitol USA 7777962072 USED 8,00 € Original sticker attached on the cover 13 ENGINES Perpetual motion 6079 1xCD Atlantic EMI CAN 075678256929 USED 8,00 € machine 1910 FRUITGUM Simon says 2486 1xLP Buddah Helidon YU 6.23167AF EX-/VG+ 10,00 € Verty little woc COMPANY 1910 FRUITGUM Simon says-The best of 3541 1xCD Buddha BMG USA 886972424422 12,90 € COMPANY 1910 Fruitgum co. 2 CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb 23685 1xDVD Masterworks Sony EU 0888837454193 10,90 € 2 UNLIMITED Edge of heaven (5 vers.) 7995 1xCDs Byte rec. EU 5411585558049 USED 3,00 € 2 UNLIMITED Wanna get up (4 vers.) 12897 1xCDs Byte rec. EU 5411585558001 USED 3,00 € 2K ***K the millennium (3 7873 1xCDs Blast first Mute EU 5016027601460 USED 3,10 € Sample copy tracks) 2PLAY So confused (5 tracks) 15229 1xCDs Sony EU NMI 674801 2 4,00 € Incl."Turn me on" 360 GRADI Ba ba bye (4 tracks) 6151 1xCDs Universal IT 156 762-2 -

The Swell and Crash of Ska's First Wave : a Historical Analysis of Reggae's Predecessors in the Evolution of Jamaican Music

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 2014 The swell and crash of ska's first wave : a historical analysis of reggae's predecessors in the evolution of Jamaican music Erik R. Lobo-Gilbert California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes Recommended Citation Lobo-Gilbert, Erik R., "The swell and crash of ska's first wave : a historical analysis of reggae's predecessors in the evolution of Jamaican music" (2014). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 366. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes/366 This Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. Unless otherwise indicated, this project was conducted as practicum not subject to IRB review but conducted in keeping with applicable regulatory guidance for training purposes. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Erik R. Lobo-Gilbert CSU Monterey Bay MPA Recording Technology Spring 2014 THE SWELL AND CRASH OF SKA’S FIRST WAVE: A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF REGGAE'S PREDECESSORS IN THE EVOLUTION OF JAMAICAN MUSIC INTRODUCTION Ska music has always been a truly extraordinary genre. With a unique musical construct, the genre carries with it a deeply cultural, sociological, and historical livelihood which, unlike any other style, has adapted and changed through three clearly-defined regional and stylistic reigns of prominence. The music its self may have changed throughout the three “waves,” but its meaning, its message, and its themes have transcended its creation and two revivals with an unmatched adaptiveness to thrive in wildly varying regional and sociocultural climates. -

Aj Thesis Corrected.Pages

The Liminal Text: Exploring the Perpetual Process of Becoming with particular reference to Samuel Selvon’s The Lonely Londoners and George Lamming’s The Emigrants & Kitch: A Fictional Biography of The Calypsonian Lord Kitchener Anthony Derek Joseph A Thesis Submitted For The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English and Comparative Literature Goldsmiths College, University of London August 2016 Joseph 1! I hereby declare that this thesis represents my own research and creative work Anthony Joseph Joseph 2! Acknowledgements I wish to acknowledge the assistance of the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) in providing financial support to complete this work. I also express my warm and sincere thanks to my supervisors Professors Blake Morrison and Joan Anim-Addo who provided invaluable support and academic guidance throughout this process. I am also grateful to the English and Comparative Literature Department for their logistic support. Thanks to Marjorie Moss and Leonard ‘Young Kitch’ Joseph for sharing their memories. I would also like to thank Valerie Wilmer for her warmth and generosity and the calypso archivist and researcher Dmitri Subotsky, who generously provided discographies, literature, and numerous rare calypso recordings. I am grateful to my wife Louise and to my daughters Meena and Keiko for their love, encouragement and patience. Anthony Joseph London December 16 2015 Joseph 3! Abstract This practice-as-research thesis is in two parts. The first, Kitch, is a fictional biography of Aldwyn Roberts, popularly known as Lord Kitchener. Kitch represents the first biographical study of the Trinidadian calypso icon, whose arrival in Britain onboard The Empire Windrush was famously captured in Pathé footage. -

THE FATHER of MODERN CALYPSO by Justine Ketola

burgie.q 11/6/03 4:34 PM Page 3 IRVING BURGIE THE FATHER OF MODERN CALYPSO By Justine Ketola “Colgate John Henry Comedy Show” radio program. Based on the qual- How many of you, nationals or foreign-born, have reached ity of this material, the focus of the show changed to a Caribbean theme. Sangster Airport in Montego Bay, Jamaica to be serenaded by As Mr. Burgie recalls, “It was a big smash, and right after the show we got together and did the recording, and it was the biggest hit that they’d ever folk singers with songs like “Island in the Sun” and “Kingston had at that time. It was the first album to sell a million copies.” This recording was Harry Belafonte’s debut album, Calypso, which Market”? Many of these classics were written by Irving was released by RCA in 1956. The album was number one on the Bill- board charts for 32 consecutive weeks. Mr. Burgie had written eight of Burgie, long considered one of the greatest composers of the 11 songs featured on this album. What followed was an illustrious career as a songwriter. “I followed that Caribbean music, whose songs have sold over 100 million up with two more albums; Belafonte actually recorded 34 of my songs in all,” notes Burgie. Two additional records came out within a five-year peri- records by artists throughout the world. He is the cre- od: Belafonte Sings of the Caribbean and Jump Up Calypso. These albums reached the top of the charts all over the world. -

Pd Soul Power D

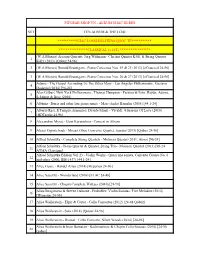

Mediendossier trigon-film SOUL POWER von Jeffrey Levy-Hinte, USA/Congo VERLEIH: trigon-film Limmatauweg 9 5408 Ennetbaden Tel: 056 430 12 30 Fax: 056 430 12 31 [email protected] www.trigon-film.org MEDIENKONTAKT Tel: 056 430 12 35 [email protected] BILDMATERIAL www.trigon-film.org MITWIRKENDE Regie: Jeffrey Levy-Hinte Kamera: Paul Goldsmith Kevin Keating Albert Maysles Roderick Young Montage: David Smith Produzenten: David Sonenberg, Leon Gast Produzenten Musikfestival Hugh Masekela, Stewart Levine Dauer: 93 Minuten Sprache/UT: Englisch/Französisch/d/f MUSIKER/ IN DER REIHENFOLGE IHRES ERSCHEINENS “Godfather of Soul” James Brown J.B.’s Bandleader & Trombonist Fred Wesley J.B.’s Saxophonist Maceo Parker Festival / Fight Promoter Don King “The Greatest” Muhammad Ali Concert Lighting Director Bill McManus Festival Coordinator Alan Pariser Festival Promoter Stewart Levine Festival Promoter Lloyd Price Investor Representative Keith Bradshaw The Spinners Henry Fambrough Billy Henderson Pervis Jackson Bobbie Smith Philippé Wynne “King of the Blues” B.B. King Singer/Songwriter Bill Withers Fania All-Stars Guitarist Yomo Toro “La Reina de la Salsa” Celia Cruz Fania All-Stairs Bandleader & Flautist Johnny Pacheco Trio Madjesi Mario Matadidi Mabele Loko Massengo "Djeskain" Saak "Sinatra" Sakoul, Festival Promoter Hugh Masakela Author & Editor George Plimpton Photographer Lynn Goldsmith Black Nationalist Stokely Carmichael a.k.a. “Kwame Ture” Ali’s Cornerman Drew “Bundini” Brown J.B.’s Singer and Bassist “Sweet" Charles Sherrell J.B.’s Dancers — “The Paybacks” David Butts Lola Love Saxophonist Manu Dibango Music Festival Emcee Lukuku OK Jazz Lead Singer François “Franco” Luambo Makiadi Singer Miriam Makeba Spinners and Sister Sledge Manager Buddy Allen Sister Sledge Debbie Sledge Joni Sledge Kathy Sledge Kim Sledge The Crusaders Kent Leon Brinkley Larry Carlton Wilton Felder Wayne Henderson Stix Hooper Joe Sample Fania All-Stars Conga Player Ray Barretto Fania All Stars Timbali Player Nicky Marrero Conga Musician Danny “Big Black” Ray Orchestre Afrisa Intern. -

Chanting up Zion: Reggae As Productive Mechanism for Repatriated Rastafari In

Chanting up Zion: Reggae as Productive Mechanism for Repatriated Rastafari in Ethiopia David Aarons A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2017 Reading Committee: Shannon Dudley, Chair Giulia Bonacci Katell Morand Christina Sunardi Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music i @Copyright 2017 David Aarons ii University of Washington Abstract Chanting up Zion: Reggae as Productive Mechanism for Repatriated Rastafari in Ethiopia David Aarons Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Shannon Dudley Ethnomusicology Since the 1960s, Rastafari from Jamaica and other countries have been “returning” to Ethiopia in the belief that it is their Promised Land, Zion. Based on extensive ethnographic research in Ethiopia between 2015 and 2017, this project examines the ways in which repatriated Rastafari use music to transform their Promised Land into a reality amidst various challenges. Since they are denied legal citizenship, Rastafari deploy reggae in creative and strategic ways to gain cultural citizenship and recognition in Ethiopia. This research examines how reggae music operates as a productive mechanism, that is, how human actors use music to produce social and tangible phenomena in the world. Combining theories on music’s productive capabilities with Rastafari ideologies on word-sound, this research further seeks to provide deeper insight into the ways Rastafari effect change through performative arts. I examine how Rastafari mobilize particular discourses that both challenge and reproduce hegemonic systems, creating space for themselves in Ethiopia through music. Rastafari use reggae in strategic ways to insert themselves into the contested national narratives of Ethiopia, and participate in the practice of space-making in Addis Ababa and Shashemene through sound projects. -

For Immediate Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Dr. Jonathan Greenland, Senior Director, the National Gallery of Jamaica, (876) 922 1561. [email protected]. – The untold half of how Jamaican music conquered the world. KINGSTON, JA. JAN 16, 2020: The Ministry of Culture, Gender and Sports, the National Gallery of Jamaica (NGJ) and the Jamaican Music Museum in association with La Philharmonie de Paris are pleased to present the exhibition Jamaica, Jamaica!, which opens on February 2, 2020 at11:00am and closes on June 28, 2020. Initially launched at Philharmonie de Paris in 2017 and titled after the eponymous 1985 hit song by Brigadier “The General” Jerry, Jamaica, Jamaica! examines how the tiny Caribbean island of Jamaica has become an extraordinary force in the world heritage and history of music. Jamaica, Jamaica! brings together rare memorabilia, photographs, visual art, audio recordings and footage unearthed from Jamaica's best museums and most elusive collectors and studios, while collaborating with legendary local visual artists to convey the essence of a true Jamaican music experience. Teeming with creativity and innovation, Jamaica has produced some of the major musical currents in today's popular music landscape; yet, its rich history and diversity is often overshadowed by its most famous icon, reggae superstar Bob Marley. This exhibition aims at showcasing a broader vision that has allowed the world to know the island's music, by digging deep into its past and present in search for the roots of "rebel music", beyond the cliché and the postcard. Page 1 of 6 The most ambitious exhibition ever staged on the topic, Jamaica, Jamaica! celebrates the musical innovations born on the island in its specific historic and social contexts, unveiling the story behind the musical genres of kumina, revival, mento, ska, rocksteady, reggae, dub and dancehall - as well as the impact of the local sound system culture, street culture, and visual arts on today's global pop culture. -

Jamaican Canadian Music in Toronto in the 1970S and 1980S

Jamaican Canadian Music in Toronto in the 1970s and 1980s: A Preliminary History by Keith McCuaig A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario May 18th, 2012 ©2012 Keith McCuaig Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-91556-1 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-91556-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Nhạc Lossless-Hiess Quốc Tế*********** ****************Classical

FITGEAR SHOP.VN - ALBUM NHẠC HI-RES STT TÊN ALBUM & THỂ LOẠI **********NHẠC LOSSLESS-HIESS QUỐC TẾ*********** ****************CLASSICAL (1.28T) ***************** (W.A.Mozart) Arcanto Quartett, Jorg Widmann - Clarinet Quintet K581 & String Quartet 1 K421 (2013) [Qobuz 24-96] 2 (W.A.Mozart) Ronald Brautigam - Piano Concertos Nos. 19 & 23 (2013) [eClassical 24-96] 3 (W.A.Mozart) Ronald Brautigam - Piano Concertos Nos. 20 & 27 (2013) [eClassical 24-96] Adams - The Gospel According To The Other Mary - Los Angeles Philharmonic, Gustavo 4 Dudamel (2014) [96-24] Alan Gilbert, New York Philharmonic, Thomas Hampson - Passion & Pain. Haydn, Adams, 5 Schubert & Berg (2010) 6 Albéniz - Iberia and other late piano music - Marc-André Hamelin (2005) [44.1-24] Alberto Rasi, Il Tempio Armonico; Davide Monti - Vivaldi. 4 Seasons Of Love (2010) 7 [HDTracks 24-96] 8 Alexandros Myrat - Eleni Karaindrou - Concert in Athens 9 Alexei Ogrintchouk - Mozart Oboe Concerto, Quartet, Sonata (2013) [Qobuz 24-96] 10 Alfred Schnittke - Complete String Quartets - Molinari Quartet (2011, Atma) [96-24] Alfred Schnittke - Piano Quartet & Quintet, String Trio - Molinari Quartet (2013) [96-24 11 ATMA Classique] Alfred Schnittke Edition Vol.23 - Violin Works - Quasi una sonata, Concerto Grosso No. 6 12 and other (2006, BIS-1437) [44.1-24] 13 Alice Coote - Handel Arias (2014) [Hyperion 24-96] 14 Alice Sara Ott - Wonderland (2016) [FLAC 24-48] 15 Alice Sara Ott - Chopin Complete Waltzes (2010) [24-96] Alina Ibragimova & Steven Osborne - Prokofiev. Violin Sonatas; Five Melodies -

1 Music and the Rise of Caribbean Nationalism: the Jamaican Case Gregory Freeland Department of Political Science California

1 Music and the Rise of Caribbean Nationalism: The Jamaican Case Gregory Freeland Department of Political Science California Lutheran University (805) 493-3477 [email protected] 2 Abstract Caribbean nationalism emerged in many ways, but music played a vital role in furnishing emotion and ideological cohesion, and fueled the excitement and sustainability of nationalist identification leading up and following independence. This study employs the musical form, ska, to exemplify how music generated a sense of nationalism in Jamaica during the late 1950s and early 1960s, and as such provided strength for independence stability and some of the courage and excitement that sustained it through its early manifestation. Music created metaphorical and emotional meanings as well as political meanings through lyrics and rhythms that helped frame independence as more than an image of freedom from colonial rule. This study utilizes interviews, music lyrics, and literature to conclude that a cultural force, like, music, created a stronger sense of nationalism among Jamaicans, which facilitated the rise of a cultural uniqueness and collective identity. 1 History has shown that music profoundly shapes the goals and objectives of a people moving toward collective identity, cultural nationalism, and political independence. Music also transmits ideologies and political demands to adherents and activists of political, cultural, and social movements. This musical effect played out dramatically in the rise of Caribbean nationalism.1 Caribbean nationalism emerged in many ways, but music played a vital role in furnishing emotion and ideological cohesion, and fueled the excitement and sustainability of nationalist identification. This effect is exemplified with, for example, merengue in the Dominican Republic, calypso in Trinidad-Tobago, and rumba in Cuba.