The Role of Education in Addressing the Challenges of the Twenty-First Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles Roberts Autograph Letters Collection MC.100

Charles Roberts Autograph Letters collection MC.100 Last updated on January 06, 2021. Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections Charles Roberts Autograph Letters collection Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................7 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 9 110.American poets................................................................................................................................. 9 115.British poets.................................................................................................................................... 16 120.Dramatists........................................................................................................................................23 130.American prose writers...................................................................................................................25 135.British Prose Writers...................................................................................................................... 33 140.American -

Download the Annual Review PDF 2016-17

Annual Review 2016/17 Pushing at the frontiers of Knowledge Portrait of Dr Henry Odili Nwume (Brasenose) by Sarah Jane Moon – see The Full Picture, page 17. FOREWORD 2016/17 has been a memorable year for the country and for our University. In the ever-changing and deeply uncertain world around us, the University of Oxford continues to attract the most talented students and the most talented academics from across the globe. They convene here, as they have always done, to learn, to push at the frontiers of knowledge and to improve the world in which we find ourselves. One of the highlights of the past twelve months was that for the second consecutive year we were named the top university in the world by the Times Higher Education Global Rankings. While it is reasonable to be sceptical of the precise placements in these rankings, it is incontrovertible that we are universally acknowledged to be one of the greatest universities in the world. This is a privilege, a responsibility and a challenge. Other highlights include the opening of the world’s largest health big data institute, the Li Ka Shing Centre for Health Information and Discovery, and the launch of OSCAR – the Oxford Suzhou Centre for Advanced Research – a major new research centre in Suzhou near Shanghai. In addition, the Ashmolean’s success in raising £1.35 million to purchase King Alfred’s coins, which included support from over 800 members of the public, was a cause for celebration. The pages that follow detail just some of the extraordinary research being conducted here on perovskite solar cells, indestructible tardigrades and driverless cars. -

Regulations of the University of Birmingham Section 3 2020-21

Regulations of the University of Birmingham Section 3 2020-21 REGULATIONS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF BIRMINGHAM SECTION 3 - HUMAN RESOURCE MATTERS Executive Brief Sets out the Regulations to be followed relating to academic appointments, promotions and conferment of titles; award of honorary academic titles; exceptional and study leave from a University post; and patents and intellectual property rights. Page 1 of 14 Regulations of the University of Birmingham Section 3 2020-21 Section 3: Human Resource Matters 3.1 Appointment to a Vacant Chair 3.1.1 An Electoral Board shall be established by the Promotions and Titles Committee in respect of each vacant Chair to make a recommendation to the Vice-Chancellor. Where there is a vacancy both for a Chair and the Headship of a Principal Academic Unit the Electoral Board shall advise the University Executive Board regarding the appointment to the Headship. 3.1.2 An Electoral Board shall be chaired by the Vice-Chancellor and Principal or, if absent, a Vice-Principal or a Pro Vice-Chancellor, except in circumstances prescribed by clauses 3.1.7 or 3.1.8 below. 3.1.3 The Head of College concerned shall be an ex-officio member of an Electoral Board except in circumstances prescribed by Sub-regulation 3.1.8 below. 3.1.4 (a) Unless he or she wishes to be considered for the vacant chair, the Head of College concerned shall recommend to the Promotions and Titles Committee three Professors, at least one of whom shall be from outside the Principal Academic Unit concerned. 3.1.4 (b) Where the Chair is established in a Principal Academic Unit the Head of which is a member of the non-Professorial staff, the Head of Principal Academic Unit may be nominated by the Head of College concerned for appointment to the Electoral Board in place of one of the Professors referred to in Regulation 3.1.4(1). -

125 Years of Women in Medicine

STRENGTH of MIND 125 Years of Women in Medicine Medical History Museum, University of Melbourne Kathleen Roberts Marjorie Thompson Margaret Ruth Sandland Muriel Denise Sturtevant Mary Jocelyn Gorman Fiona Kathleen Judd Ruth Geraldine Vine Arlene Chan Lilian Mary Johnstone Veda Margaret Chang Marli Ann Watt Jennifer Maree Wheelahan Min-Xia Wang Mary Louise Loughnan Alexandra Sophie Clinch Kate Suzannah Stone Bronwyn Melissa Dunbar King Nicole Claire Robins-Browne Davorka Anna Hemetek MaiAnh Hoang Nguyen Elissa Stafford Trisha Michelle Prentice Elizabeth Anne McCarthy Fay Audrey Elizabeth Williams Stephanie Lorraine Tasker Joyce Ellen Taylor Wendy Anne Hayes Veronika Marie Kirchner Jillian Louise Webster Catherine Seut Yhoke Choong Eva Kipen Sew Kee Chang Merryn Lee Wild Guineva Joan Protheroe Wilson Tamara Gitanjali Weerasinghe Shiau Tween Low Pieta Louise Collins Lin-Lin Su Bee Ngo Lau Katherine Adele Scott Man Yuk Ho Minh Ha Nguyen Alexandra Stanislavsky Sally Lynette Quill Ellisa Ann McFarlane Helen Wodak Julia Taub 1971 Mary Louise Holland Daina Jolanta Kirkland Judith Mary Williams Monica Esther Cooper Sara Kremer Min Li Chong Debra Anne Wilson Anita Estelle Wluka Julie Nayleen Whitehead Helen Maroulis Megan Ann Cooney Jane Rosita Tam Cynthia Siu Wai Lau Christine Sierakowski Ingrid Ruth Horner Gaurie Palnitkar Kate Amanda Stanton Nomathemba Raphaka Sarah Louise McGuinness Mary Elizabeth Xipell Elizabeth Ann Tomlinson Adrienne Ila Elizabeth Anderson Anne Margeret Howard Esther Maria Langenegger Jean Lee Woo Debra Anne Crouch Shanti -

Languages of Power in the Age of Richard Ii Staley, Languages of Power 10/15/04 12:03 PM Page Ii Staley, Languages of Power 10/15/04 12:03 PM Page Iii

Staley, Languages of Power 10/15/04 12:03 PM Page i languages of power in the age of richard ii Staley, Languages of Power 10/15/04 12:03 PM Page ii Staley, Languages of Power 10/15/04 12:03 PM Page iii Lynn Staley languages of power in the age of Richard II the pennsylvania state university press university park, pennsylvania Staley, Languages of Power 10/15/04 12:03 PM Page iv Disclaimer: Some images in the original version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Staley, Lynn, 1947– Languages of power in the age of Richard II / Lynn Staley. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0–271–02518–2 (alk. paper) 1. English literature—Middle English, 1100–1500—History and criticism. 2. Power (Social sciences) in literature. 3. Great Britain—History—Richard II, 1377–1399—Historiography. 4. Richard II, King of England, 1367–1400—In literature. 5. Politics and literature—Great Britain—History—To 1500. 6. Power (Social sciences)—Great Britain—History—To 1500. 7. Literature and history—Great Britain—History—To 1500. 8. Chaucer, Geoffrey, d. 1400—Political and social views. 9. Kings and rulers in literature. 10. Monarchy in literature. I. Title. pr275 .p67S73 2005 820.9'358—dc22 2004013330 Copyright © 2005 The Pennsylvania State University All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Published by The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, PA 16802-1003 The Pennsylvania State University Press is a member of the Association of American University Presses. -

List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007

Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007 A - J Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 A complete listing of all Fellows and Foreign Members since the foundation of the Society A - J July 2007 List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 The list contains the name, dates of birth and death (where known), membership type and date of election for all Fellows of the Royal Society since 1660, including the most recently elected Fellows (details correct at July 2007) and provides a quick reference to around 8,000 Fellows. It is produced from the Sackler Archive Resource, a biographical database of Fellows of the Royal Society since its foundation in 1660. Generously funded by Dr Raymond R Sackler, Hon KBE, and Mrs Beverly Sackler, the Resource offers access to information on all Fellows of the Royal Society since the seventeenth century, from key characters in the evolution of science to fascinating lesser- known figures. In addition to the information presented in this list, records include details of a Fellow’s education, career, participation in the Royal Society and membership of other societies. Citations and proposers have been transcribed from election certificates and added to the online archive catalogue and digital images of the certificates have been attached to the catalogue records. This list is also available in electronic form via the Library pages of the Royal Society web site: www.royalsoc.ac.uk/library Contributions of biographical details on any Fellow would be most welcome. -

TRAC Development Group

TRAC Development Group Chair Professor Neville Ford Pro-Vice-Chancellor, University of Chester Members from institutions Matthew Andrews University Secretary and Registrar, University of Gloucestershire Andrew Connolly Chief Financial Officer, University of Exeter Nicola Davies Director of Finance, University of Liverpool Stephen Forster Chief Financial Officer, Aberystwyth University Professor Richard Greene Pro Vice-Chancellor for Research & Knowledge Exchange, Manchester Metropolitan University Trevor Gabriele Chief Finance Officer, University of the West of Scotland Catherine Jones TRAC Accountant, University of York Professor Neal Juster Senior Vice-Principal and Deputy Vice-Chancellor, University of Glasgow Professor Jackie Labbe Pro Vice-Chancellor (Academic), De Montfort University Greg Langston Assistant Finance Director, Coventry University Professor Gordon Love Head of Department for Computer Science, Durham University Sarah Randall-Paley Director of Finance, Lancaster University Professor Jane Saffell Deputy Principal Education, St George's, University of London Ewa Szynkowska Head of Financial Accounting, Imperial College London Graham Willard Senior Finance Analyst (TRAC), University College London Members from funders and sector bodies Andrew Dicken Deputy Head of Funding Assurance, UK Research and Innovation Liz Furey Director of Finance, Harper Adams University; GuildHE Chris Hale Director of Policy, Universities UK Steve Keightley Senior Financial Analyst, Scottish Funding Council Caroline Low Director of Planning and Corporate Strategy, University of Lincoln; Higher Education Strategic Planners Association (HESPA) Diane Rowland Senior Financial Assurance Manager, Higher Education Funding Council for Wales Karen Sergiou Director Research Services, University College London; Association of Research Managers and Administrators (ARMA) Heather Williams Principal Analyst, Office for Students May 2020 For more information about TRAC and the TRAC Development Group, see www.trac.ac.uk . -

Court – Wednesday 18 April 2012 Principal's

Court – Wednesday 18 April 2012 Principal’s Report Items A: For Discussion 1. Restructuring Review – action plan At the last meeting, Court heard from Professor Nolan that the project team had started work on the seven main commitments arising from the review of restructuring. The full report and action plan is at Annex 1. Professor Nolan will brief Court. 2. Scottish Funding Council Grant, 2012/13 On 30 March, the SFC issued the University's grant letter for 2012/13. Much of the information was already provided to us in December 2011 in the Indicative Grant Letter. However, a number of items have been changed and others clarified. There are a significant number of grant lines that will come under review over the next 1-3 years. The main points to note are: Teaching 1. SFC have re-confirmed the full restoration of the 2010/11 Teaching Units of Resource and Funded places and then added a 2.6% uplift to the Teaching Units of Resource. However, the additional allocation for strategically important high cost areas is now £3.6M compared to £4.1M in the Indicative Grant Letter. 2. Our overall Teaching Funding for 2012/13 is £83.6M compared to the December 2011 forecast of £83.7M (reduction of £118k). 3. Of the additional 300 funded places in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) allocated in 2012/13, Glasgow has received 50 of these places. By 2015/16 this will rise to 200 additional STEM places for Glasgow. 4. An additional 15 Funded places have been made available for the Dumfries Campus in 2012/13. -

Vice-Chancellor and Principal Information Pack

DEPUTY VICE-CHANCELLOR (EDUCATION) Information pack sydney.edu.au The University of Sydney acknowledges that its campuses and facilities sit on the ancestral lands of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, who have for thousands of generations exchanged knowledge for the benefit of all. DEPUTY VICE-CHANCELLOR (EDUCATION) Information pack Welcome from the Vice-Chancellor ....3 About the University of Sydney .............4 Organisational structure .......................10 Strategic achievements .......................... 11 Higher education in Australia ...............12 Living and working in Sydney ................ 14 About the role ......................................... 16 How to apply ........................................... 20 Cover: Looking across Eastern Avenue from the New Law Building to the Anderson Stuart Building and the Quadrangle Left (and inside back cover): Spine 3, 2018, concrete, concrete oxide, hematite, artwork on the side of the Carslaw Building by Dale Harding, descendant of the Bidjara, Ghungalu and Garingbal peoples Page 2 Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Education) - Information Pack sydney.edu.au WELCOME FROM THE VICE-CHANCELLOR Thank you for expressing an interest in the key leadership role of Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Education) at the University of Sydney. The position oversees our whole-of-University Education Portfolio, the hallmarks of which are its deep commitment to continued innovation in teaching and learning and providing our students with an optimal University experience. continue to broaden our footprint -

SBH NL 2018 Aug V25.Pages

St Benet’s NewsAugust 2018 INSIDE THIS ISSUE Welcome to the latest issue of the St Benet’s newsletter. For this edition, we have followed the example of many of the other colleges in producing an annual, rather than a termly edition. We are therefore featuring a pictorial “Year in the Life of Benet’s”, giving a flavour of what has been happening here over the past academic year. Undoubtedly, the main event was the 120th Anniversary Gaudy, held in the House of Commons on Friday 3rd November 2017, hosted by alum, Damian Green MP. 176 Benetians and friends came together on that evening to celebrate the Hall’s history. It was particularly pleasing to have three Benet’s Masters together for the event. The present Master, Prof Werner G Jeanrond was joined by Fr Henry Wansbrough OSB (1990-2004) and Fr Felix Stephens OSB (2007-2012). As many of you will have heard, Prof Werner Jeanrond, will end his six-year term as Master of Benet’s at the end of August 2018 and will take up the Chair of Dogmatics at the University of Oslo. Under his leadership, Benet’s has successfully gone fully co-educational, has acquired a much-needed second building, has expanded its graduate numbers considerably, and is extremely well-regarded across the University — the Vice-Chancellor, Prof Louise Richardson has publicly stated: “Oxford needs St Benet’s”. Recruitment for Werner’s replacement will start in the autumn and news of the Interim Master will be announced shortly. I will also be leaving my role as Alumni Officer & PA to the Master at the end of August. -

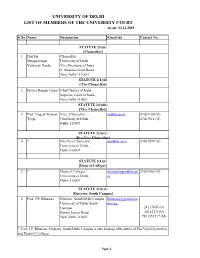

UNIVERSITY of DELHI LIST of MEMBERS of the UNIVERSITY COURT As On: 12.11.2018

UNIVERSITY OF DELHI LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE UNIVERSITY COURT As on: 12.11.2018 S.No Name Designation Email ids Contact No. STATUTE 2(1)(i) [Chancellor] 1 Hon'ble Chancellor Muppavarapu University of Delhi Venkaiah Naidu Vice-President of India 6, Maulana Azad Road, New Delhi - 110011 STATUTE 2(1)(ii) [ Pro-Chancellor] 2 Justice Ranjan Gogoi Chief Justice of India Supreme Court of India New Delhi-110001 STATUTE 2(1)(iii) [Vice-Chancellor] 3 Prof. Yogesh Kumar Vice -Chancellor [email protected] 27001100 (O) Tyagi University of Delhi, 27667011 (O) Delhi-110007 STATUTE 2(1)(iv) [Pro-Vice-Chancellor] 4 * Pro-Vice-Chancellor [email protected] 27667899 (O) University of Delhi, Delhi-110007 STATUTE 2(1)(v) [Dean of Colleges] 5 * Dean of Colleges [email protected]. 27667066 (O) University of Delhi, in Delhi-110007 STATUTE 2(1)(vi) [Director, South Campus] 6 Prof. J.P. Khurana Director, South Delhi Campus khuranaj@genomein University of Delhi South dia.org Campus 24117005 (O) Benito Jaurez Road 24112231(O) New Delhi-110021 9811351217 (M) * Prof. J.P. Khurana, Director, South Delhi Campus is also looking after duties of Pro-Vice-Chancellor and Dean of Colleges Page 1 STATUTE 2(1)(vii) [Tresurer] 7 Shri T.S. Kripanidhi Treasurer kripanidhits@yahoo. 9818928162 University of Delhi co.in Delhi-110007 STATUTE 2(1)(viii) [All Former Vice-Chancellor] 8 Prof. Upendra Baxi A-51, Law Appartments, [email protected] 8447944106 (M) Karkardoma, n Delhi-110092 baxiupendra@gmail. 9 Prof. Vrajendra Raj 5928, DLF Qutab Enclave, 9350292197 (M) Mehta Phase-IV, Gurgaon-122002 10 Prof. -

Vice-Principal & Pro Vice-Chancellor (Global Engagement)

Vice-Principal & Pro Vice-Chancellor (Global Engagement) // Appointment details // Overview of UWS 2016 June 2016 CONTENTS 03 Vice-Principal and Pro Vice-Chancellor – Key Result Areas 04 Planning and Organisation 04 Communications and Working Relationships 05 Most Challenging Part of Job 05 Person Specification 06 Terms and Conditions 07 Application 09 UWS – An Overview 10 Creating a 21st Century Learning Environment – UWS Campuses 13 UWS Truths 14 Research 15 Living and Working in the West of Scotland 17 National Recognition Vice Principal and Pro Vice-Chancellor JOB DESCRIPTION Job Title Vice-Principal & Pro Vice-Chancellor (Global Engagement) Reporting to Principal and Vice-Chancellor Job Summary As a key member of the Vice-Chancellor’s Executive Group, the Vice-Principal carries executive corporate responsibilities for the success of the University and specific executive responsibilities for internationalisation of the University’s activities and reputation. Dimensions Staffing: Overall responsibility for staff within the International Centre and close liaison with Assistant Deans (International), as agreed with the Principal. The total staffing is 16 FTEs. Financial: Directly accountable for the International Centre’s core budget and responsible for the achievement of financial targets across areas of responsibility. The total staffing and operational budgets for the Centre are circa £2m. Key Result Areas: Corporate Responsibilities 1. Participate in and accept shared executive responsibility for the corporate leadership, management and development of the University. 2. Represent the University as appropriate by chairing or serving on internal and external committees, working and advisory groups as required by the Principal and Vice-Chancellor. This will include the International Advisory Committee and the London Campus Leadership Group.