Strengthening Our Roots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Provincial Solidarities: a History of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour

provincial solidarities Working Canadians: Books from the cclh Series editors: Alvin Finkel and Greg Kealey The Canadian Committee on Labour History is Canada’s organization of historians and other scholars interested in the study of the lives and struggles of working people throughout Canada’s past. Since 1976, the cclh has published Labour / Le Travail, Canada’s pre-eminent scholarly journal of labour studies. It also publishes books, now in conjunction with AU Press, that focus on the history of Canada’s working people and their organizations. The emphasis in this series is on materials that are accessible to labour audiences as well as university audiences rather than simply on scholarly studies in the labour area. This includes documentary collections, oral histories, autobiographies, biographies, and provincial and local labour movement histories with a popular bent. series titles Champagne and Meatballs: Adventures of a Canadian Communist Bert Whyte, edited and with an introduction by Larry Hannant Working People in Alberta: A History Alvin Finkel, with contributions by Jason Foster, Winston Gereluk, Jennifer Kelly and Dan Cui, James Muir, Joan Schiebelbein, Jim Selby, and Eric Strikwerda Union Power: Solidarity and Struggle in Niagara Carmela Patrias and Larry Savage The Wages of Relief: Cities and the Unemployed in Prairie Canada, 1929–39 Eric Strikwerda Provincial Solidarities: A History of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour / Solidarités provinciales: Histoire de la Fédération des travailleurs et travailleuses du Nouveau-Brunswick David Frank A History of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour david fra nk canadian committee on labour history Copyright © 2013 David Frank Published by AU Press, Athabasca University 1200, 10011 – 109 Street, Edmonton, ab t5j 3s8 isbn 978-1-927356-23-4 (print) 978-1-927356-24-1 (pdf) 978-1-927356-25-8 (epub) A volume in Working Canadians: Books from the cclh issn 1925-1831 (print) 1925-184x (digital) Cover and interior design by Natalie Olsen, Kisscut Design. -

Legislative Assembly

JOURNALS OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE PROVINCE OF NEW BRUNSWICK From the 24th day of October to the 17th day of November, 2017 From the 5th day of December to the 21st day of December, 2017 From the 30th day of January to the 9th day of February, 2018 From the 13th day of March to the 16th day of March, 2018 Being the Fourth Session of the Fifty-Eighth Legislative Assembly Fredericton, N.B. 2017-2018 MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Fourth Session of the Fifty-Eighth Legislative Assembly Speaker: the Honourable Christopher Collins Constituency Member Residence Albert Brian Keirstead Lower Coverdale Bathurst East-Nepisiguit-Saint Isidore Hon. Denis Landry Trudel Bathurst West-Beresford Hon. Brian Kenny Beresford Campbellton-Dalhousie* Vacant Caraquet Hédard Albert Saint-Simon Carleton Stewart Fairgrieve Hartland Carleton-Victoria Hon. Andrew Harvey Florenceville-Bristol Carleton-York Carl Urquhart Upper Kingsclear Dieppe Hon. Roger Melanson Dieppe Edmundston-Madawaska Centre** 0DGHODLQH'XEp (GPXQGVWRQ Fredericton-Grand Lake Pam Lynch Fredericton Fredericton North Hon. Stephen Horsman Fredericton Fredericton South David Coon Fredericton Fredericton West-Hanwell Brian Macdonald Fredericton Fredericton-York Kirk MacDonald Stanley Fundy-The Isles-Saint John West Hon. Rick Doucet St. George Gagetown-Petitcodiac Ross Wetmore Gagetown Hampton Gary Crossman Hampton Kent North Bertrand LeBlanc Rogersville Kent South Hon. Benoît Bourque Bouctouche Kings Centre William (Bill) Oliver Keirsteadville Madawaska Les Lacs-Edmundston Hon. Francine Landry Edmundston Memramcook-Tantramar Bernard LeBlanc Memramcook Miramichi Hon. Bill Fraser Miramichi Miramichi Bay-Neguac Hon. Lisa Harris Miramichi Moncton Centre Hon. Christopher Collins Moncton Moncton East Monique A. LeBlanc Moncton Moncton Northwest Ernie Steeves Upper Coverdale Moncton South Hon. -

Legislative Assembly

JOURNALS OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE PROVINCE OF NEW BRUNSWICK From the 6th day of February to the 6th day of July, 2007 Being the First Session of the Fifty-Sixth Legislative Assembly Fredericton, N.B. 2007 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY First Session of the Fifty-Sixth Legislative Assembly Speaker: the Honourable Eugene McGinley, Q.C. Constituency Member Residence Albert Wayne Steeves Lower Coverdale Bathurst Brian Kenny Bathurst Campbellton-Restigouche Centre Roy Boudreau Campbellton Caraquet Hon. Hédard Albert Caraquet Carleton Dale Graham Centreville Centre-Péninsule–Saint-Sauveur Hon. Denis Landry Trudel Charlotte-Campobello Antoon (Tony) Huntjens St. Stephen Charlotte-The Isles Hon. Rick Doucet St. George Dalhousie-Restigouche East Hon. Donald Arseneault Black Point Dieppe Centre-Lewisville Cy (Richard) Leblanc Dieppe Edmundston–Saint-Basile Madeleine Dubé Edmundston Fredericton-Fort Nashwaak Hon. Kelly Lamrock Fredericton Fredericton-Lincoln Hon. Greg Byrne, Q.C. Fredericton Fredericton-Nashwaaksis Hon. Thomas J. (T.J.) Burke, Q.C. Fredericton Fredericton-Silverwood Richard (Rick) Miles Fredericton Fundy-River Valley Hon. Jack Keir Grand Bay-Westfield Grand Falls–Drummond–Saint-André Hon. Ronald Ouellette Grand Falls Grand Lake-Gagetown Hon. Eugene McGinley, Q.C. Chipman Hampton-Kings Bev Harrison Hampton Kent Hon. Shawn Graham Mundleville Kent South Claude Williams Saint-Antoine Kings East Bruce Northrup Sussex Lamèque-Shippagan-Miscou Paul Robichaud Pointe-Brûlé Madawaska-les-Lacs Jeannot Volpé Saint-Jacques Memramcook-Lakeville-Dieppe Bernard LeBlanc Memramcook Miramichi Bay-Neguac Hon. -

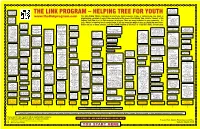

LINK Ptogram Decisional Tree English

School based Free legal advice programs / groups: clinic: Call Chimo Health action groups, 450-HELP (4357) THE LINK PROGRAM – HELPING TREE FOR YOUTH Teen mom groups, etc. or 1-800-667-5005 www.thelinkprogram.com This HELPING TREE is designed to inform you about resources. If you, or someone you care about, is Helplines: School based u Chimo 450-HELP (4357) programs/groups: experiencing a problem in any of the areas listed at the base of the Helping Tree, follow a "branch" of the or 1-800-667-5005 Antibullying, Peer Helping Tree (flow chart) to find resources to help you. There are many resources in your community – it's u Kids Help Phone Helpers, Making 1-800-668-6868 Waves, etc just a matter of knowing how to contact them. If you are uncertain where to turn, or would like more infor- www.kidshelpphone.ca u Telecare 811 Frontier College mation on any of these services, call the CHIMO Helpline at 450-4357 or 1-800-667-5005, 24 hours/day. (Talk to a nurse) (tutoring) Helplines: 450-7923 or School based Employment services/ Q Centre Commun- u Chimo programs/groups: programs for special 1-877-450-7923 autaire Sainte-Anne Helplines: 450-HELP (4357) or specific needs: 453-2731 Birthright 1-800-550-4900 School based Teens Against Tobacco u Chimo 450-HELP (4357) Other local services for grief: programs/groups: or 1-800-667-5005 Use (TATU) u Premier's Council on or 454-1890 u Other services to meet or 1-800-667-5005 Local churches & organizations Clubs, Peer helpers, Sports, Kids Help Phone the Status of Disabled u Sylvan Learning Teens Against Drinking basic needs: Kids Help Phone 1-800-668-6868 Helplines: Support Groups such as Youth Engagement, etc 1-800-668-6868 Persons 444-3000 or Q 1-866-363-6546 & Driving (TADD) Federation des Courthouses: www.kidshelpphone.ca u GriefShare, youth groups, etc. -

DYCD Sites for 8.12

DYCD Sites Operating BCO District 8/12 Address Zip Code Site Type team XFSC 7 X001 335 EAST 152 STREET 10451 DYCD Only Team 1 Bronx XFSC 7 X025 811 EAST 149 STREET 10455 DYCD Only Team 1 Bronx XFSC 10 X033 2424 JEROME AVENUE 10468 DYCD Only Team 1 Bronx XFSC 11 X041 3352 OLINVILLE AVENUE 10467 DYCD Only Team 1 Bronx XFSC 8 X048 1290 SPOFFORD AVENUE 10474 DYCD Only Team 1 Bronx XFSC 9 X058 459 EAST 176 STREET 10457 DYCD Only Team 1 Bronx XFSC 8 X071 3040 ROBERTS AVENUE 10461 DYCD Only Team 1 Bronx XFSC; Charter 8 X093 1535 STORY AVENUE 10473 DYCD Only Team 1 Bronx XFSC 10 X094 3530 KINGS COLLEGE PLACE 10467 DYCD Only Team 1 Bronx XFSC 11 X096 2385 OLINVILLE AVENUE 10467 DYCD Only Team 1 Bronx XFSC 11 X097 1375 MACE AVENUE 10469 DYCD Only Team 1 Bronx XFSC 8 X100 800 TAYLOR AVENUE 10473 DYCD Only Team 1 Bronx XFSC 9 X104 1449 SHAKESPEARE AVENUE 10452 DYCD Only Team 1 Bronx XFSC 11 X106 1514 OLMSTEAD AVENUE 10462 DYCD Only Team 1 Bronx XFSC 8 X107 1695 SEWARD AVENUE 10473 DYCD Only Team 1 Bronx XFSC 11 X121 2750 THROOP AVENUE 10469 DYCD Only Team 1 Bronx XFSC 9 X126 175 WEST 166 STREET 10452 DYCD Only Team 1 Bronx XFSC 8 X130 750 PROSPECT AVENUE 10455 DYCD Only Team 1 Bronx XFSC 12 X134 1330 BRISTOW STREET 10459 DYCD Only Team 1 Bronx XFSC 8 X140 916 EAGLE AVENUE 10456 DYCD Only Team 1 Bronx XFSC 12 X167 1970 WEST FARMS ROAD 10460 DYCD Only Team 1 Bronx XFSC 10 X206 2280 AQUEDUCT AVENUE 10468 DYCD Only Team 1 Bronx XFSC 10 X279 2100 WALTON AVENUE 10453 DYCD Only Team 1 Bronx XFSC 10 X843 2641 GRAND CONCOURSE 10468 DYCD Only Team 1 Bronx -

PO T of the CHIEF CTORAL O FCER DES ELECTIO

THIRTY-FIRST GENERAL EL£CTION OCTOBER 13. 1987 PO T OF THE CHIEF CTORAL o FCER PROVINCE OF NEW BRUNSWICK DES ELECTIO DU WIC SUR LE TRENTE ET UNIEMES ELECTIONS GENERALES TENUES LE 13 OCTOBRE 1987 TO THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF NEW BRUNSWICK MR. SPEAKER: I have the honour to submit to you the Return of the General Election held on October 13th, 1987. The Thirtieth Legislative Assembly was dissolved on August 29th, 1987 and Writs ordering a General Election for October 13th, 1987 were issued on August 29th, 1987, and made returnable on October 26th, 1987. Four By-Elections have been held since the General Election of 1982 and have been submitted under separate cover, plus being listed in this Report. This Office is proposing that consideration be given to having the Chief Electoral Officer and his or her staff come under the Legislature or a Committee appointed by the Legislature made up of all Parties represented in the House. The other proposal being that a specific period of time be attached to the appointments of Returning Officers as found in Section 9 of the Elections Act. Respectfully submitted, February 15, 1988 SCOVIL S. HOYT Acting Chief Electoral Officer A L'ASSEMBLEE LEGISLATIVE DU NOUVEAU-BRUNSWICK MONSIEUR LE PRESIDENT, J'ai I'honneur de vous presenter les resultats des elections generales qui se sont tenues Ie 13 octobre 1987. La trentieme Assemblee legislative a ete dissoute Ie 29 Staff of Chief Elec aoOt 1987 et les brefs ordonnant la tenue d'elections Personnel du bUrE generales Ie 13 octobre 1987 ont ete em is Ie 29 aout 1987 et Election Schedule rapportes Ie 260ctobre 1987. -

2018 Annual Report

Board of Directors The New York Cares Board of Directors are dedicated professionals who bring a wealth of public and private sector experience and are committed to driving community impact through volunteerism. President Board Members Paul J. Taubman James L. Amine, Head of Private Credit Chairman and CEO, PJT Partners Opportunities, Credit Suisse Rene Brinkley, Brand Marketing Manager, CNBC 2018 Vice President Audrey Choi, Chief Marketing Officer and Chief Kathy Behrens Sustainability Officer, Morgan Stanley Annual President, Social Responsibility and Player K. Don Cornwell, Partner, PJT Partners Programs, National Basketball Association Joyce Frost, Partner, Riverside Risk Advisors LLC Report Vice President Gail B. Harris, President Emeritus, John B. Ehrenkranz Board Director and Investor Chief Investment Officer, Julie Turaj Ehrenkranz Partners L.P. Robert Walsh, Chief Financial Officer, Evercore Partners Janet Zagorin, Principal, Opal Strategy LLC Vice President Adam Zotkow, Partner, Goldman Sachs Michael Graham Senior Managing Director & Country Honorary Board Members Head - USA, OMERS Private Equity USA Edward Adler, Partner, RLM Finsbury Richard Bilotti, Head of Technology, Media, Secretary and Telecommunications Research, Keith A. Grossman P. Schoenfeld Asset Management President, TIME Cheryl Cohen Effron Ken Giddon, President, Rothman’s We Co-Treasurer Union Square Neil K. Dhar Partner, Head of Financial Services, Sheldon Hirshon, ESQ, SIH PriceWaterhouseCoopers LLP Enterprises, a Division of MC Acquisitions LLC Co-Treasurer Robert Levitan, Chief Executive Jeanne Straus Officer, Pando Networks, Inc. President, Straus News, Our Town, West David Rabin, Partner, The Lambs Side Spirit, Our Town Downtown Club and Double Seven Michael Schlein, President and believe CEO, Accion International Rising Leaders Council The Rising Leaders Council is a group of 40 young professionals who spearhead volunteer projects and raise funds in support of New York Cares. -

Fredericton and Upper River Valley | Community Resources

PAGE 1 OF 6 NBBWCP | NEW BRUNSWICK BREAST & WOMEN'S CANCER PARTNERSHIP Fredericton and Upper River Valley | Community Resources SERVICE LOCATION CONTACT BREAST CANCER The program encourages women between the ages of 50-74 to SCREENING be screened every two years at one of the 16 mammography sites across the province. Women residing in NB who are 50 - 74 years of age and have no signs, symptoms or previous diagnosis of breast cancer can self- refer to breast cancer screening by contacting one of the screening sites. Women aged 40-49 or over 74 who have no signs, symptoms or previous diagnosis of breast cancer require a referral from a primary health-care provider. Breast cancer screening services are offered at a number of facilities: Breast Cancer Screening Perth-Andover Program Local: 506-273-7181 Hospital Hotel-Dieu of St. Joseph Breast Cancer Screening Waterville Program Toll free: 1-800-656-7575 Upper River Valley Hospital Breast Cancer Screening Oromocto Program, Local: 506-357-4747 Oromocto Public Hospital www.nbbwcp-pcscfnb.ca [email protected] November 01, 2018 10:14:20 AM AST PAGE 2 OF 6 NBBWCP | NEW BRUNSWICK BREAST & WOMEN'S CANCER PARTNERSHIP SERVICE LOCATION CONTACT CERVICAL CANCER Who can access this program? SCREENING Screening for cervical cancer using Pap tests are recommended for NB women aged 21-69 who have ever been sexually active with a partner of either gender: - Even after menopause (no longer having periods) - Even after having the HPV vaccine. Contact your primary health-care provider to discuss cervical cancer screening. Boiestown Health Centre Boiestown Local: 506-369-2700 Brunswick Community Health Fredericton Clinic Local: 506-452-6383 Central Miramichi Community Doaktown Health Centre Local: 506-365-6100 CFB Gagetown Medical Clinic Gagetown, Oromocto Local: 506-422-2000 #3270 Fredericton Junction Health Fredericton Junction Centre Local: 506-368-6501 Harvey Health Centre Harvey Local: 506-366-6400 Hotel Dieu St. -

Her Excellency, the Right Honourable Adrienne Clarkson, Governor General and Commander-In-Chief of Canada

Minister of Health Ministre de la Santé The Honourable/L'honorable Pierre S. Pettigrew Ottawa, Canada K1A 0K9 December, 2003 Her Excellency, the Right Honourable Adrienne Clarkson, Governor General and Commander-in-Chief of Canada May it please Your Excellency: The undersigned has the honour to present to Your Excellency the Annual Report on the administration and operation of the Canada Health Act for the fiscal year that ended March 31, 2003. Pierre S. Pettigrew Preface The late Justice Emmett M. Hall referred to Canada’s Medicare with the words: “Our proudest achievement in the well-being of Canadians has been in asserting that illness is burden enough in itself. Financial ruin must not compound it. That is why Medicare has been called a sacred trust and we must not allow that trust to be betrayed.” The adoption of the Canada Health Act is an important achievement in the evolution of Canada’s health care system. The Act puts into words our commitment to a universal, publicly funded health care system based on the needs of Canadians, not their ability to pay. The five principles of the Act are the cornerstone of the Canadian health care system, and they reflect the values that inspired our system. April 1, 2004, will mark the 20th anniversary of the Act. In 2003, the provincial premiers and territorial leaders reached a historic agreement with Canada’s former Prime Minister, the Right Honourable Jean Chrétien, to improve the quality, accessibility and sustainability of our public health care system. On this occasion, the first ministers reaffirmed their commitment to the five principles of public health insurance in Canada: universality, accessibility, portability, comprehensiveness and public administration. -

Provincial Legislatures

PROVINCIAL LEGISLATURES ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL LEGISLATORS ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL MINISTRIES ◆ COMPLETE CONTACT NUMBERS & ADDRESSES Completely updated with latest cabinet changes! 144 / PROVINCIAL RIDINGS PROVINCIAL RIDINGS British Columbia Surrey-Green Timbers ............................Sue Hammell ....................................154 Surrey-Newton........................................Harry Bains.......................................152 Total number of seats ................79 Surrey-Panorama Ridge..........................Jagrup Brar........................................153 Liberal..........................................46 Surrey-Tynehead.....................................Dave S. Hayer...................................154 New Democratic Party ...............33 Surrey-Whalley.......................................Bruce Ralston....................................156 Abbotsford-Clayburn..............................John van Dongen ..............................157 Surrey-White Rock .................................Gordon Hogg ....................................154 Abbotsford-Mount Lehman....................Michael de Jong................................153 Vancouver-Burrard.................................Lorne Mayencourt ............................155 Alberni-Qualicum...................................Scott Fraser .......................................154 Vancouver-Fairview ...............................Gregor Robertson..............................156 Bulkley Valley-Stikine ...........................Dennis -

49-Madawaska Les Lacs-Edmundston Madawaska-Les

KEDGWICK RIVER Legend / Légende Provincial Electoral Dsitricts / Circonscription Électorales Provinciales Polling Divisions / Section de votes Municipalities-Towns-Villages / Municipalités-Villes-Villages 1-Restigouche West Restigouche-Ouest F irs La t ke 37 SAINT-JOSEPH-DE-MADAWASKA 4949494949 36 S I O U Q O R I h c ch RUISSEAU RICHARD c h R L A E N S G S IN U T 8 O R R A h M ch RUISSEAU c c h T E DASTOU I R O Q 40 U O c R h I S A P U N E O G T T I S T A 6 D ch ch F BERNIER DSL DE ch BÉLONIE SAINT-JACQUES c h B E R L U c O IS h 39 N S R E E c A É A h N S ch McCoy S U 35 I G R O - O 6 B c ch LEVESQUE h h Q c B T U ch ROUSSEL ch DE A O I R S E I ET MARTIN L B S L'AÉROPORT E L Y A É J ch S h S S c A O IN B ch RUISSEAU- T ch ch DU BLOC M À-LUNTS ch CHAREST IC c H h E R H L A ch DUBÉ ch WALSH C N N G Y 6 L h c ch DES CHUTES H E ch DE LA PÉPINIÈRE P D E S R ch DEUXIÈME O U -J LO O SAULT T P U S h E ch c 39 L L E v T 34 a T ch E E T T T a O E v ru BELLEFLEUR U L S L ch LANDRY S E A U ch OLD NO 2 ch ROUSSEL IN O ch DEUXIÈME SAULT ch CASTONGUAY T ch TURGEON ch ch PARENT RA ch OLD POWER NG c 2 ch ST-ONGE h c h C B O c N h ³² A U I R T c I T h S O O H U M R 31 L h EP U c S R T S A E JO h N Y - I S R G ST E c c A I h À 4 R J IN O E T V U S U A SAINT-JACQUES S O E U IE r P S A ru MAXIME u S c L U I E M h E U D V D A R R O 0 A h D I S B 3 V S c h I A E c 8 I 38 U H 32 W È ch OLIVIER- R T 2 R E A c IT E 33 BOUCHER S h U E R R K IN c -T A ch ST-PIERRE IS h A A 27 c 26 O h R N L É V c - B ch ALBERT ch PARADIS D h G -À U 29 h P I V 48-Edmundston-Madawaska -

Restigouche West Gilles.Lepage@Gnb

Names (party) Riding E-Mail Gilles LePage (L) Restigouche West [email protected] Daniel Guitard (L) Restigouche-Chaleur [email protected] René Legacy (L) Bathurst West-Beresford [email protected] Lisa Harris (L) Miramichi Bay-Neguac [email protected] Michelle Conroy (PA) Miramichi [email protected] Jake Stewart (PC) Southwest Miramichi-Bay du Vin [email protected] Greg Turner (PC) Moncton South [email protected] Hon. Mike Holland (PC) Albert [email protected] Hon. Tammy Scott-Wallace (PC) Sussex-Fundy-St. Martins [email protected] Hon. Gary Crossman (PC) Hampton [email protected] Hon. Hugh J. A. (Ted) Flemming, Q.C. (PC) Rothesay [email protected] Hon. Trevor A. Holder (PC) Portland-Simonds [email protected] Hon. Arlene Dunn (PC) Saint John Harbour [email protected] Hon. Dorothy Shephard (PC) Saint John Lancaster [email protected] Hon. Bill Oliver (PC) Kings Centre [email protected] Kathy Bockus (PC) Saint Croix [email protected] Kris Austin (PA) Fredericton-Grand Lake [email protected] Jeff Carr (PC) New Maryland-Sunbury [email protected] Hon. Jill Green (PC) Fredericton North [email protected] Ryan P. Cullins (PC) Fredericton-York [email protected] Hon. Dominic Cardy (PC) Fredericton West-Hanwell [email protected] Gilles LePage (L) Restigouche West [email protected] Michelle Conroy (PA) Miramichi [email protected] Greg Turner (PC) Moncton South [email protected] Kathy Bockus (PC) Saint Croix [email protected] René Legacy (L) Bathurst West-Beresford [email protected] Lisa Harris (L) Miramichi Bay-Neguac [email protected] Ryan P.