Total Disaster and Total Justice: Responses to Man-Made Tragedy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Truman Fire Forum Report

Photo Courtesy of Harry S. Truman Library The 17th Annual President Harry S. Truman Legacy Symposium and the President Truman Fire Forum Key West, Florida May 5-7, 2019 ii “The serious losses in life and property resulting annually from fires cause me deep concern. I am sure that such unnecessary waste can be reduced. The substantial progress made in the science of fire prevention and fire protection in this country during the past forty years convinces me that the means are available for limiting this unnecessary destruction.” iii Introduction It is my pleasure to present the report of the 17th Annual Harry S. Truman Legacy Symposium and President Truman Fire Forum held in Key West, Florida, on May 5-7, 2019. The symposium is an annual educational event hosted by the Harry S. Truman Little White House and the Key West Harry S. Truman Foundation. This year’s theme, “Truman’s Legacy Toward Fire Prevention, Fire Safety, and Historic Preservation”, centered on the achievements of the 1947 President’s Conference on Fire Prevention and its follow-up reports (Appendix A). On May 6, 1947 President Truman, in response to a series of deadly fires, gathered the country’s best and brightest to convene the 1947 President’s National Conference on Fire Prevention. During the three-day event, those in attendance dedicated themselves to finding solutions to America’s deadly fire problem, the antithesis of an industrialized nation. Thus, fire prevention became a critical part of building a safer nation. Seventy-two years later, the National Fallen Firefighters Foundation is taking a page from President Truman’s playbook. -

Country Travel Risk Summaries

COUNTRY RISK SUMMARIES Powered by FocusPoint International, Inc. Report for Week Ending September 19, 2021 Latest Updates: Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, India, Israel, Mali, Mexico, Myanmar, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Turkey, Ukraine and Yemen. ▪ Afghanistan: On September 14, thousands held a protest in Kandahar during afternoon hours local time to denounce a Taliban decision to evict residents in Firqa area. No further details were immediately available. ▪ Burkina Faso: On September 13, at least four people were killed and several others ijured after suspected Islamist militants ambushed a gendarme patrol escorting mining workers between Sakoani and Matiacoali in Est Region. Several gendarmes were missing following the attack. ▪ Cameroon: On September 14, at least seven soldiers were killed in clashes with separatist fighters in kikaikelaki, Northwest region. Another two soldiers were killed in an ambush in Chounghi on September 11. ▪ India: On September 16, at least six people were killed, including one each in Kendrapara and Subarnapur districts, and around 20,522 others evacuated, while 7,500 houses were damaged across Odisha state over the last three days, due to floods triggered by heavy rainfall. Disaster teams were sent to Balasore, Bhadrak and Kendrapara districts. Further floods were expected along the Mahanadi River and its tributaries. ▪ Israel: On September 13, at least two people were injured after being stabbed near Jerusalem Central Bus Station during afternoon hours local time. No further details were immediately available, but the assailant was shot dead by security forces. ▪ Mali: On September 13, at least five government soldiers and three Islamist militants were killed in clashes near Manidje in Kolongo commune, Macina cercle, Segou region, during morning hours local time. -

COCOANUT GROVE FIRE November 28, 1942

COCOANUT GROVE FIRE November 28, 1942 List of Injured The following is the list of causalities as a result of the Cocoanut Grove Fire that occurred on November 28, 1942. The list of casualties is drawn from the official report of the Committee On Public Safety of the City of Boston. Although the report lists 489 fatalities and 166 injured, the generally accepted total of fatalities is 492. The total of 166 injured includes only those persons who were admitted to hospitals. Last Name First Name/M.I. Address City/Town State Additional Info Facility # Alweis Paul Harvard University Cambridge MA . Fort Banks 1 Anastos Leonede --- Gay Head MA U.S. Coast Guard Chelsea Naval Hospital 2 Arrivelle Adelaide 52 Avon St. Lawrence MA . Boston City Hospital 3 Balkan Estelle 113 Pleasant St. Winthrop MA . Boston City Hospital 4 Bean Robert 415 Somerville Ave. Somerville MA . Boston City Hospital 5 Bellinger Albert --- Whitinsville MA . Mass. General Hospital 6 Bouvier Louise 377 South St. Southbridge MA . Boston City Hospital 7 Bowen Kathleen 26 Gates St. South Boston MA . Boston City Hospital 8 Bowen Margaret 26 Gates St. South Boston MA . Mass. General Hospital 9 Bruck Fred 72 Foster St. Cambridge MA . Boston City Hospital 10 Burns Robert E. Jr. 21 Mellon Hall Cambridge MA Harvard University Fort Banks 11 Burns William G. Harvard University Cambridge MA Naval Supply School Peter Bent Brigham/Chelsea Naval Hospital 12 Byrne James 14 Longfellow St. Dorchester MA . Boston City Hospital 13 Campos Melissa Broadway Hotel Boston MA . Boston City Hospital 14 Canning Mary 22 Abbott St. -

Publication of ANA Massachusetts PO Box 285, Milton, MA 02186 617-990-2856 [email protected]

Massachusetts Report on Nursing The Official Publication of ANA Massachusetts PO Box 285, Milton, MA 02186 617-990-2856 [email protected] Quarterly Circulation 130,000 Do you know this nurse? See page 5 Vol. 12 No. 2 March 2018 Receiving this newsletter does not mean that you are an ANA Massachusetts member. Please join ANA Massachusetts today and help to promote the Nursing Profession. Go to: www.ANAMass.org Join ANA Massachusetts today! 2018: Year of Advocacy Join Us at Lobby/Advocacy Day Christina Saraf and Myra Cacace know our personal Co-Chairs of ANA MA Health Policy Committee representatives and senators, and The American Nurses Association has offering to be a resource to them Clio’s Corner: designated 2018 as the Year of Advocacy. In gives us a greater voice in policy formation. 75th Anniversary Memorial of concert with this initiative, ANA Massachusetts Hillary Clinton stated “If you believe you invites you to participate in our own Lobby Day, can make a difference, not just in politics, in the Cocoanut Grove Fire also known as Advocacy Day, on Tuesday, March public service, in advocacy around all these 20th. Massachusetts nurses from all disciplines important issues, then you have to be prepared Pages 4-5 will meet at the Massachusetts State House, in to accept that you are not going to get 100 percent the Great Hall of Flags, to learn about important approval.” These words teach us that we must issues for nurses and the patients and families be nurse advocates in order to gain support for we serve. -

Johnstown, Pennsylvania and Vicinity

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, DIRECTOR BULLETIN 447 MINERAL RESOURCES j . ' OF JOHNSTOWN, PENNSYLVANIA AND VICINITY BY W. C. PHALEN AND LAWRENCE MARTIN SURVEYED IN COOPERATION WITH THE TOPOGRAPHIC AND GEOLOGIC SURVEY COMMISSION OF PENNSYLVANIA WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1911 CONTENTS. Introduction.............................................................. 9 Geography............... ; .................................................. 9 Location.............................................................. 9 Commercial geography................................................... 9 Topography............................................................... 10 Relief...........................................................:.... 10 Surveys......... V.................................................... 11 Triangulation................................. fi. .................. 11 Spirit leveling.................................................... 13 Stratigraphy.............................................................. 14 General statement.................................................... 14 Quaternary system..................................................... 15 Recent river deposits (alluvium).................................... 15 Pleistocene deposits............................................... 15 Carboniferous system. r ............................................... 16 Pennsylvanian series ............................................... 16 Conemaugh formation......................................... -

Preakness Stakes .Fifty-Three Fillies Have Competed in the Preakness with Start in 1873: Rfive Crossing the Line First The

THE PREAKNESS Table of Contents (Preakness Section) History . .P-3 All-Time Starters . P-31. Owners . P-41 Trainers . P-45 Jockeys . P-55 Preakness Charts . P-63. Triple Crown . P-91. PREAKNESS HISTORY PREAKNESS FACTS & FIGURES RIDING & SADDLING: WOMEN & THE MIDDLE JEWEL: wo people have ridden and sad- dled Preakness winners . Louis J . RIDERS: Schaefer won the 1929 Preakness Patricia Cooksey 1985 Tajawa 6th T Andrea Seefeldt 1994 Looming 7th aboard Dr . Freeland and in 1939, ten years later saddled Challedon to victory . Rosie Napravnik 2013 Mylute 3rd John Longden duplicated the feat, win- TRAINERS: ning the 1943 Preakness astride Count Judy Johnson 1968 Sir Beau 7th Fleet and saddling Majestic Prince, the Judith Zouck 1980 Samoyed 6th victor in 1969 . Nancy Heil 1990 Fighting Notion 5th Shelly Riley 1992 Casual Lies 3rd AFRICAN-AMERICAN Dean Gaudet 1992 Speakerphone 14th RIDERS: Penny Lewis 1993 Hegar 9th Cynthia Reese 1996 In Contention 6th even African-American riders have Jean Rofe 1998 Silver’s Prospect 10th had Preakness mounts, including Jennifer Pederson 2001 Griffinite 5th two who visited the winners’ circle . S 2003 New York Hero 6th George “Spider” Anderson won the 1889 Preakness aboard Buddhist .Willie Simms 2004 Song of the Sword 9th had two mounts, including a victory in Nancy Alberts 2002 Magic Weisner 2nd the 1898 Preakness with Sly Fox “Pike”. Lisa Lewis 2003 Kissin Saint 10th Barnes was second with Philosophy in Kristin Mulhall 2004 Imperialism 5th 1890, while the third and fourth place Linda Albert 2004 Water Cannon 10th finishers in the 1896 Preakness were Kathy Ritvo 2011 Mucho Macho Man 6th ridden by African-Americans (Alonzo Clayton—3rd with Intermission & Tony Note: Penny Lewis is the mother of Lisa Lewis Hamilton—4th on Cassette) .The final two to ride in the middle jewel are Wayne Barnett (Sparrowvon, 8th in 1985) and MARYLAND MY Kevin Krigger (Goldencents, 5th in 2013) . -

Owners, Kentucky Derby (1875-2017)

OWNERS, KENTUCKY DERBY (1875-2017) Most Wins Owner Derby Span Sts. 1st 2nd 3rd Kentucky Derby Wins Calumet Farm 1935-2017 25 8 4 1 Whirlaway (1941), Pensive (’44), Citation (’48), Ponder (’49), Hill Gail (’52), Iron Liege (’57), Tim Tam (’58) & Forward Pass (’68) Col. E.R. Bradley 1920-1945 28 4 4 1 Behave Yourself (1921), Bubbling Over (’26), Burgoo King (’32) & Brokers Tip (’33) Belair Stud 1930-1955 8 3 1 0 Gallant Fox (1930), Omaha (’35) & Johnstown (’39) Bashford Manor Stable 1891-1912 11 2 2 1 Azra (1892) & Sir Huon (1906) Harry Payne Whitney 1915-1927 19 2 1 1 Regret (1915) & Whiskery (’27) Greentree Stable 1922-1981 19 2 2 1 Twenty Grand (1931) & Shut Out (’42) Mrs. John D. Hertz 1923-1943 3 2 0 0 Reigh Count (1928) & Count Fleet (’43) King Ranch 1941-1951 5 2 0 0 Assault (1946) & Middleground (’50) Darby Dan Farm 1963-1985 7 2 0 1 Chateaugay (1963) & Proud Clarion (’67) Meadow Stable 1950-1973 4 2 1 1 Riva Ridge (1972) & Secretariat (’73) Arthur B. Hancock III 1981-1999 6 2 2 0 Gato Del Sol (1982) & Sunday Silence (’89) William J. “Bill” Condren 1991-1995 4 2 0 0 Strike the Gold (1991) & Go for Gin (’94) Joseph M. “Joe” Cornacchia 1991-1996 3 2 0 0 Strike the Gold (1991) & Go for Gin (’94) Robert & Beverly Lewis 1995-2006 9 2 0 1 Silver Charm (1997) & Charismatic (’99) J. Paul Reddam 2003-2017 7 2 0 0 I’ll Have Another (2012) & Nyquist (’16) Most Starts Owner Derby Span Sts. -

1930S Greats Horses/Jockeys

1930s Greats Horses/Jockeys Year Horse Gender Age Year Jockeys Rating Year Jockeys Rating 1933 Cavalcade Colt 2 1933 Arcaro, E. 1 1939 Adams, J. 2 1933 Bazaar Filly 2 1933 Bellizzi, D. 1 1939 Arcaro, E. 2 1933 Mata Hari Filly 2 1933 Coucci, S. 1 1939 Dupuy, H. 1 1933 Brokers Tip Colt 3 1933 Fisher, H. 0 1939 Fallon, L. 0 1933 Head Play Colt 3 1933 Gilbert, J. 2 1939 James, B. 3 1933 War Glory Colt 3 1933 Horvath, K. 0 1939 Longden, J. 3 1933 Barn Swallow Filly 3 1933 Humphries, L. 1 1939 Meade, D. 3 1933 Gallant Sir Colt 4 1933 Jones, R. 2 1939 Neves, R. 1 1933 Equipoise Horse 5 1933 Longden, J. 1 1939 Peters, M. 1 1933 Tambour Mare 5 1933 Meade, D. 1 1939 Richards, H. 1 1934 Balladier Colt 2 1933 Mills, H. 1 1939 Robertson, A. 1 1934 Chance Sun Colt 2 1933 Pollard, J. 1 1939 Ryan, P. 1 1934 Nellie Flag Filly 2 1933 Porter, E. 2 1939 Seabo, G. 1 1934 Cavalcade Colt 3 1933 Robertson, A. 1 1939 Smith, F. A. 2 1934 Discovery Colt 3 1933 Saunders, W. 1 1939 Smith, G. 1 1934 Bazaar Filly 3 1933 Simmons, H. 1 1939 Stout, J. 1 1934 Mata Hari Filly 3 1933 Smith, J. 1 1939 Taylor, W. L. 1 1934 Advising Anna Filly 4 1933 Westrope, J. 4 1939 Wall, N. 1 1934 Faireno Horse 5 1933 Woolf, G. 1 1939 Westrope, J. 1 1934 Equipoise Horse 6 1933 Workman, R. -

A Brief History of the Charlotte Fire Department

A Brief History of the Charlotte Fire Department The Volunteers Early in the nineteenth century Charlotte was a bustling village with all the commercial and manufacturing establishments necessary to sustain an agrarian economy. The census of 1850, the first to enumerate the residents of Charlotte separately from Mecklenburg County, showed the population to be 1,065. Charlotte covered an area of 1.68 square miles and was certainly large enough that bucket brigades were inadequate for fire protection. The first mention of fire services in City records occurs in 1845, when the Board of Aldermen approved payment for repair of a fire engine. That engine was hand drawn, hand pumped, and manned by “Fire Masters” who were paid on an on-call basis. The fire bell hung on the Square at Trade and Tryon. When a fire broke out, the discoverer would run to the Square and ring the bell. Alerted by the ringing bell, the volunteers would assemble at the Square to find out where the fire was, and then run to its location while others would to go the station, located at North Church and West Fifth, to get the apparatus and pull it to the fire. With the nearby railroad, train engineers often spotted fires and used a special signal with steam whistles to alert the community. They were credited with saving many lives and much property. The original volunteers called themselves the Hornets and all their equipment was hand drawn. The Hornet Company purchased a hand pumper in 1866 built by William Jeffers & Company of Pawtucket, Rhode Island. -

2018 Media Guide NYRA.Com 1 FIRST RUNNING the First Running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park Took Place on a Thursday

2018 Media Guide NYRA.com 1 FIRST RUNNING The first running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park took place on a Thursday. The race was 1 5/8 miles long and the conditions included “$200 each; half forfeit, and $1,500-added. The second to receive $300, and an English racing saddle, made by Merry, of St. James TABLE OF Street, London, to be presented by Mr. Duncan.” OLDEST TRIPLE CROWN EVENT CONTENTS The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is the oldest of the Triple Crown events. It predates the Preakness Stakes (first run in 1873) by six years and the Kentucky Derby (first run in 1875) by eight. Aristides, the winner of the first Kentucky Derby, ran second in the 1875 Belmont behind winner Calvin. RECORDS AND TRADITIONS . 4 Preakness-Belmont Double . 9 FOURTH OLDEST IN NORTH AMERICA Oldest Triple Crown Race and Other Historical Events. 4 Belmont Stakes Tripped Up 19 Who Tried for Triple Crown . 9 The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is one of the oldest stakes races in North America. The Phoenix Stakes at Keeneland was Lowest/Highest Purses . .4 How Kentucky Derby/Preakness Winners Ran in the Belmont. .10 first run in 1831, the Queens Plate in Canada had its inaugural in 1860, and the Travers started at Saratoga in 1864. However, the Belmont, Smallest Winning Margins . 5 RUNNERS . .11 which will be run for the 150th time in 2018, is third to the Phoenix (166th running in 2018) and Queen’s Plate (159th running in 2018) in Largest Winning Margins . -

Four Historic Neighborhoods of Johnstown, Pennsylvania

HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY/HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD Clemson University 3 1604 019 774 159 The Character of a Steel Mill City: Four Historic Neighborhoods of Johnstown, Pennsylvania ol ,r DOCUMENTS fuBUC '., ITEM «•'\ pEPQS' m 20 1989 m clewson LIBRARY , j„. ft JL^s America's Industrial Heritage Project National Park Service Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/characterofsteelOOwall THE CHARACTER OF A STEEL MILL CITY: Four Historic Neighborhoods of Johnstown, Pennsylvania Kim E. Wallace, Editor, with contributions by Natalie Gillespie, Bernadette Goslin, Terri L. Hartman, Jeffrey Hickey, Cheryl Powell, and Kim E. Wallace Historic American Buildings Survey/ Historic American Engineering Record National Park Service Washington, D.C. 1989 The Character of a steel mill city: four historic neighborhoods of Johnstown, Pennsylvania / Kim E. Wallace, editor : with contributions by Natalie Gillespie . [et al.]. p. cm. "Prepared by the Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record ... at the request of America's Industrial Heritage Project"-P. Includes bibliographical references. 1. Historic buildings-Pennsylvania-Johnstown. 2. Architecture- Pennsylvania-Johnstown. 3. Johnstown (Pa.) --History. 4. Historic buildings-Pennsylvania-Johnstown-Pictorial works. 5. Architecture-Pennsylvania-Johnstown-Pictorial works. 6. Johnstown (Pa.) -Description-Views. I. Wallace, Kim E. (Kim Elaine), 1962- . II. Gillespie, Natalie. III. Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record. IV. America's Industrial Heritage Project. F159.J7C43 1989 974.877-dc20 89-24500 CIP Cover photograph by Jet Lowe, Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record staff photographer. The towers of St. Stephen 's Slovak Catholic Church are visible beyond the houses of Cambria City, Johnstown. -

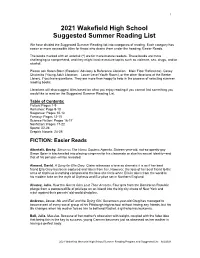

2021 Wakefield High School Suggested Summer Reading List

1 2021 Wakefield High School Suggested Summer Reading List We have divided the Suggested Summer Reading list into categories of reading. Each category has easier or more accessible titles for those who desire them under the heading: Easier Reads. The books marked with an asterisk (*) are for more mature readers. These books are more challenging to comprehend, and they might involve mature topics such as violence, sex, drugs, and/or alcohol. Please ask Karen Stern (Readers’ Advisory & Reference Librarian—Main Floor Reference), Casey Chwiecko (Young Adult Librarian—Lower Level Youth Room), or the other librarians at the Beebe Library, if you have questions. They are more than happy to help in the process of selecting summer reading books. Librarians will also suggest titles based on what you enjoy reading if you cannot find something you would like to read on the Suggested Summer Reading List. Table of Contents: Fiction: Pages 1-9 Romance: Page 9-10 Suspense: Pages 10-12 Fantasy: Pages 12-15 Science Fiction: Pages 16-17 Nonfiction: Pages 17-22 Sports: 22-24 Graphic Novels: 24-25 FICTION: Easier Reads Albertalli, Becky. Simon vs The Homo Sapiens Agenda. Sixteen-year-old, not-so-openly-gay Simon Spier is blackmailed into playing wingman for his classmate or else his sexual identity--and that of his pen pal--will be revealed. Almond, David. A Song for Ella Grey. Claire witnesses a love so dramatic it is as if her best friend Ella Grey has been captured and taken from her. However, the loss of her best friend to the arms of Orpheus is nothing compared to the loss she feels when Ella is taken from the world in his modern take on the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice set in Northern England.