Identifying the Exchange Rate Regime in the Republic of Moldova

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moldova: the Failing Champion of European Integration by Vladimir Soloviev Translated and Edited by Olga Khvostunova

TRANSITIONS FORUM GLOBAL TRANSITIONS | JULY 2014 Moldova: The Failing Champion of European Integration by Vladimir Soloviev translated and edited by Olga Khvostunova www.li.com www.prosperity.com TRANSITIONS FORUM ABOUT THE LEGATUM INSTITUTE The Legatum Institute is a charitable public policy think-tank whose mission is to help people lead more prosperous lives. The Institute defines prosperity as wellbeing, not just wealth. Its Legatum Prosperity Index™ assesses a wide range of indicators including education, health, social capital, entrepreneurship, and personal freedom to rank 142 countries. Published annually, the Index has become an essential tool for governments around the world. Through research programmes including The Culture of Prosperity, Transitions Forum, and the Economics of Prosperity, the Institute seeks to understand what drives and restrains national success and individual flourishing. The Institute co-publishes with Foreign Policy magazine, the Democracy Lab, whose on-the-ground journalists report on political transitions around the world. The Legatum Institute is based in London and an independent member of the Legatum Group, a private investment group with a 27-year heritage of global investment in businesses and programmes that promote sustainable human development. www.li.com www.prosperity.com http://democracylab.foreignpolicy.com TRANSITIONS FORUM CONTENTS Introduction 3 The EU-Moldova Relationship: Success in Theory 4 The Corruption Issue 7 Compromised Judiciary 9 System Failure 11 Challenges to the Free Media 13 Anchor of Separatism 15 Opposition without a Position 17 Conclusion 18 References 19 About the Author inside back About Our Partner inside back About the Legatum Institute inside front TRANSITIONS lecture series | 2 TRANSITIONS FORUM Introduction In 2014, the European Union signed an association agreement with Moldova and agreed to let Moldovans travel to the EU without visas. -

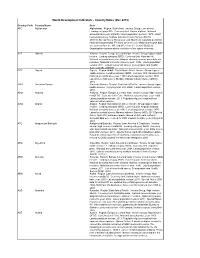

Euro Exchange Rates - 2019

Euro Exchange Rates - 2019 Α/Α COUNTRY CURRENCY CODE June 2019 1 Albania Leck ALL 122,90 2 Argentina Argentine Peso ARS 49,40 3 Armenia Armenian Dram AMD 537,70 4 Australia Australian Dollar AUD 1,61 5 Bahamas Bahamian Dollar BSD 1,12 6 Bahrain Bahraini Dinar BHD 0,42 7 Bangladesh Taka BDT 94,18 8 Barbados Barbados Dollar BBD 2,23 9 Belarus NEW Belarusian Ruble BYN 2,34 10 Bolivia Boliviano BOB 7,75 11 Bosnia Herzegovina Bosnia Marka BAM 1,96 12 Botswana Pula BWP 12,02 13 Brazil Brazilian Real BRL 4,45 14 Bulgaria Bulgarian Lev BGN 1,96 15 Burkina Faso CFA Franc BCEAO XOF 655,96 16 Burundi Burundi Franc BIF 2.042,95 17 Cameroon CFA Franc BEAC XAF 655,96 18 Canada Canadian Dollar CAD 1,50 19 Chad CFA Franc BEAC XAF 655,96 20 Chile Chilean Peso CLP 784,80 21 China Yuan Renminbi CNY 7,70 22 Colombia Colombian Peso COP 3.731,71 23 Congo (DemRep) Franc Congo CDF 1.844,65 24 Costa Rica Costa Rican Colon CRC 658,59 25 Croatia Kuna HRK 7,42 26 Cuba Cuban peso CUC 1,12 27 Czech Republic Czech Koruna CZK 25,63 28 Denmark Danish Krone DKK 7,46 29 Dominican Republic Dominican Peso DOP 56,35 30 Ecuador US Dollar USD 1,12 31 Egypt Egyptian pound EGP 18,82 32 Ethiopia Ethiopian Birr ETB 32,45 33 Gambia Dalasi GMD 55,34 34 Ghana Cedi GHS 5,90 35 Guinea Guinea Franc GNF 10.242,50 36 Hong Kong Hong Kong Dollar HKD 8,75 37 Hungary Forint HUF 325,85 38 Iceland Iceland Krona ISK 138,50 39 India Indian Rupee INR 77,80 40 Indonesia Rupiah IDR 15.945,22 41 Iran Iranian Rial IRR 47.061,38 42 Israel New Israeli Shekel ILS 4,05 43 Jamaica Jamaican Dollar JMD 151,84 44 Japan Japanese Yen JPY 122,12 45 Jordan Jordanian Dinar JOD 0,79 46 Kazakhstan Tenge KZT 424,24 47 Kenya Kenyan Shilling KES 113,83 48 Kuwait Kuwaiti Dinar KWD 0,34 49 Lebanon Lebanese Pound LBP 1.697,71 50 Libya Libyan Dinar LYD 1,57 51 Madagascar Malagasy Franc MGA 4.087,95 52 Malawi Kwacha MWK 803,79 53 Malaysia Malaysian Ringgit MYR 4,63 54 Maldive Is. -

Financial Crisis in Moldova - Causes and Consequences

Studia i Analizy Studies & Analyses Centrum Analiz Społeczno-Ekonomicznych CASE Center for Social and Economic Research Financial Crisis in Moldova - Causes and Consequences 192 Artur Radziwiłł, Octavian Şcerbaţchi, Constantin Zaman Warsaw, 1999 Studies & Analyses CASE No, 192: Financial Crisis in Moldova – Causes and Consequences CONTENTS MOLDOVA - BRIEF PRESENTATION..............................................................................................................3 I. MONETARY REFORM (1993-1997)...........................................................................................................6 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................................6 2. BUILDING-UP INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK .......................................................................................................6 Banking Environment ......................................................................................................................................6 Introduction of the National Currency.......................................................................................................7 The Development of Commercial Banking System ..............................................................................7 3. MONETARY POLICY.................................................................................................................................................9 Credit Allocation ................................................................................................................................................9 -

Currency List

Americas & Caribbean | Tradeable Currency Breakdown Currency Currency Name New currency/ Buy Spot Sell Spot Deliverable Non-Deliverable Special requirements/ Symbol Capability Forward Forward Restrictions ANG Netherland Antillean Guilder ARS Argentine Peso BBD Barbados Dollar BMD Bermudian Dollar BOB Bolivian Boliviano BRL Brazilian Real BSD Bahamian Dollar CAD Canadian Dollar CLP Chilean Peso CRC Costa Rica Colon DOP Dominican Peso GTQ Guatemalan Quetzal GYD Guyana Dollar HNL Honduran Lempira J MD J amaican Dollar KYD Cayman Islands MXN Mexican Peso NIO Nicaraguan Cordoba PEN Peruvian New Sol PYG Paraguay Guarani SRD Surinamese Dollar TTD Trinidad/Tobago Dollar USD US Dollar UYU Uruguay Peso XCD East Caribbean Dollar 130 Old Street, EC1V 9BD, London | t. +44 (0) 203 475 5301 | [email protected] sugarcanecapital.com Europe | Tradeable Currency Breakdown Currency Currency Name New currency/ Buy Spot Sell Spot Deliverable Non-Deliverable Special requirements/ Symbol Capability Forward Forward Restrictions ALL Albanian Lek BGN Bulgarian Lev CHF Swiss Franc CZK Czech Koruna DKK Danish Krone EUR Euro GBP Sterling Pound HRK Croatian Kuna HUF Hungarian Forint MDL Moldovan Leu NOK Norwegian Krone PLN Polish Zloty RON Romanian Leu RSD Serbian Dinar SEK Swedish Krona TRY Turkish Lira UAH Ukrainian Hryvnia 130 Old Street, EC1V 9BD, London | t. +44 (0) 203 475 5301 | [email protected] sugarcanecapital.com Middle East | Tradeable Currency Breakdown Currency Currency Name New currency/ Buy Spot Sell Spot Deliverabl Non-Deliverabl Special Symbol Capability e Forward e Forward requirements/ Restrictions AED Utd. Arab Emir. Dirham BHD Bahraini Dinar ILS Israeli New Shekel J OD J ordanian Dinar KWD Kuwaiti Dinar OMR Omani Rial QAR Qatar Rial SAR Saudi Riyal 130 Old Street, EC1V 9BD, London | t. -

The Translation Is Unofficial, for Information Purpose Only

Note: The translation is unofficial, for information purpose only Official Monitor of the Republic of Moldova No.27-29 of February 10, 2009, Art.100 REGISTERED: Minister of Justice of the Republic of Moldova Vitalie PÎRLOG No.646 of February 04, 2009 COUNCIL OF ADMINISTRATION OF THE NATIONAL BANK OF MOLDOVA DECISION No.3 of January 15, 2009 On the approval of the Regulation on the Setting of the Official Exchange Rate of Moldovan Leu against Foreign Currencies Pursuant to Art.11, 51 and 52 of the Law on the National Bank of Moldova No.548-XIII of July 21, 1995 (Official Monitor of the Republic of Moldova, 1995, No.56-57, Art.624), with further modifications and completions, Art.39 and 67 of the Law on Foreign Exchange Regulation No.62- XVI of March 21, 2008 (Official Monitor of the Republic of Moldova, 2008, No.127-130, Art.496), the Council of Administration of the National Bank of Moldova DECIDES: 1. To approve the Regulation on the Setting of the Official Exchange Rate of Moldovan Leu against Foreign Currencies (see attached). 2. To abrogate the Instruction on the Procedure of Formation, Distribution and Archiving of the Official Exchange Rate of Moldovan Leu, approved by the Decision of the Council of Administration of the National Bank of Moldova No.399 of December 23, 1999 (Official Monitor of the Republic of Moldova, 2000, No.1-4, Art.8), with further modifications and completions. Chairman of the Council of Administration Leonid TALMACI 1 APPROVED by the Decision of the Council of Administration of the National Bank of Moldova No.3 of January 15, 2009 Regulation on the Setting of the Official Exchange Rate of Moldovan Leu against Foreign Currencies (compiled version including modifications and completions as in accordance with the list*) amended and supplemented by: DEC of the NBM no. -

List of All European Countries, Capitals, Currencies & Population In

List of all European countries, capitals, currencies & population in 2019 Country Capital Population (2019) Currency Albania Tirana 2.880.917 Albanian lek Andorra Andorra la Vella 77.142 Euro Armenia Yerevan 2.958.900 Armenian dram Austria Vienna 8.955.102 Euro Azerbaijan Baku 10.067.060 Azerbaijani manat Belarus Minsk 9.452.411 Belarusian ruble Belgium Brussels 11.539.328 Euro Bosnia and Herzegovina Sarajevo 3.301.000 Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark Bulgaria Sofia 7.000.119 Bulgarian lev Croatia Zagreb 4.130.304 Croatian kuna Cyprus Nicosia 1.200.434 Euro Czechia Prague 10.689.209 Czech koruna Denmark Copenhagen 5.771.876 Danish krone Estonia Tallinn 1.325.648 Euro Finland Helsinki 5.532.156 Euro France Paris 65.129.728 Euro Georgia Tbilisi 1.200.434 Georgian lari Germany Berlin 83.517.045 Euro Greece Athens 10.473.455 Euro Hungary Budapest 9.684.679 Hungarian forint Iceland Reykjavik 339.031 Icelandic króna: second króna Ireland Dublin 4.882.495 Euro Italy Rome 60.550.075 Euro Latvia Riga 1.906.743 Euro Liechtenstein Vaduz 38.019 Swiss franc Lithuania Vilnius 2.759.627 Euro Luxembourg Luxembourg City 615.729 Euro Malta Valletta 440.372 Euro Moldova Chisinau 4.043.263 Moldovan leu Monaco Monaco 38.964 Euro Montenegro Podgorica 627.987 Euro Netherlands Amsterdam 17.097.130 Euro North Macedonia Skopje 2.083.441 Second Macedonian denar Norway Oslo 5.378.857 Norwegian krone Poland Warsaw 37.887.768 Polish złoty Portugal Lisbon 10.226.187 Euro Romania Bucharest 19.364.557 Romanian leu Russia Moscow 145.872.256 Russian ruble San Marino San Marino 33.860 Euro Serbia Belgrade 8.772.235 Serbian dinar Slovakia Bratislava 5.457.013 Euro Slovenia Ljubljana 2.078.654 Euro Spain Madrid 46.736.776 Euro Sweden Stockholm 10.036.379 Swedish krona Switzerland Bern 8.591.365 Swiss franc Turkey Ankara 83.621.817 Turkish lira Ukraine Kiev 43.993.638 Ukrainian hryvnia United Kingdom London 67.530.172 Pound sterling Vatican City Vatican City 799 Euro Source: https://197travelstamps.com/european-countries-and-capitals-list-alphabetical . -

1. Introduction

Purpose and Structure of This Report 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Purpose and Structure of This Report The purpose of this report is to highlight and analyse discrimination and in- equality in the Republic of Moldova (Moldova) and to recommend steps aimed at combating discrimination and promoting equality. The report explores long- recognised human rights problems, while also seeking to shed light upon less well-known patterns of discrimination in the country. The report brings to- and inequality in Moldova with an analysis of the laws, policies, practices and institutionsgether – for establishedthe first time to –address evidence them. of the lived experience of discrimination The report comprises four parts. Part 1 sets out its purpose and structure, the conceptual framework which has guided the work, and the research method- ology. It also provides basic information about Moldova, its history and the current political and economic situation. Part 2 presents patterns of discrimination and inequality, highlighting evidence of discrimination and inequality on the basis of a range of characteristics: race and ethnicity (with a focus on discrimination against Roma persons), disability, sexual orientation and gender identity, health status, gender, religion, language and age (with a focus on the disadvantages faced by older persons). Part 3 begins by reviewing the main international legal obligations of Mol- of the UN and Council of Europe human rights systems. It then discusses Mol- dovandova in national the field law of equalityrelated to and equality non-discrimination, and non-discrimination, within the starting frameworks with - tion and non-discrimination provisions in other legislation. Part 3 also re- viewsthe Constitution state policies before relevant examining to equality. -

Undata WDI Metadata 2015 01 23.Xlsx

World Development Indicators - Country Notes (Dec 2014) Country Code Country Name Note AFG Afghanistan Afghanistan. Region: South Asia. Income Group: Low income. Lending category: IDA. Currency Unit: Afghan afghani. National accounts base year: 2002/03 Latest population census: 1979. Latest household survey: Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS), 2010/11.Special Notes: Fiscal year end: March 20; reporting period for national accounts data: FY (from 2013 are CY). National accounts data are sourced from the IMF and differ from the Central Statistics Organization numbers due to exclusion of the opium economy. ALB Albania Albania. Region: Europe & Central Asia. Income Group: Upper middle income. Lending category: IBRD. Currency Unit: Albanian lek. National accounts base year: Original chained constant price data are rescaled. National accounts reference year: 1996. Latest population census: 2011. Latest household survey: Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), 2008/09. DZA Algeria Algeria. Region: Middle East & North Africa. Income Group: Upper middle income. Lending category: IBRD. Currency Unit: Algerian dinar. National accounts base year: 1980 Latest population census: 2008. Latest household survey: Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS), 2012. ASM American Samoa American Samoa. Region: East Asia & Pacific. Income Group: Upper middle income. Currency Unit: U.S. dollar. Latest population census: 2010. ADO Andorra Andorra. Region: Europe & Central Asia. Income Group: High income: nonOECD. Currency Unit: Euro. National accounts base year: 1990 Latest population census: 2011. Population figures compiled from administrative registers.. AGO Angola Angola. Region: Sub-Saharan Africa. Income Group: Upper middle income. Lending category: IBRD. Currency Unit: Angolan kwanza. National accounts base year: 2002 Latest population census: 1970. Latest household survey: Malaria Indicator Survey (MIS), 2011.Special Notes: April 2013 database update: Based on IMF data, national accounts data were revised for 2000 onward; the base year changed to 2002. -

Exchange Rate Statistics October 2019

Exchange rate statistics October 2019 Statistical Supplement 5 to the Monthly Report Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics October 2019 2 Deutsche Bundesbank Wilhelm-Epstein-Strasse 14 60431 Frankfurt am Main, Germany Postal address Postfach 10 06 02 60006 Frankfurt am Main The Exchange rate statistics supplement is released once Germany a month and published on the basis of Section 18 of the Tel.: +49 (0)69 9566 3512 Bundesbank Act (Gesetz über die Deutsche Bundesbank). Email: [email protected] Up-to-date information and time series are also available online at: Information pursuant to Section 5 of the German Tele- www.bundesbank.de/timeseries media Act (Telemediengesetz) can be found at: www.bundesbank.de/en/homepage/imprint Further statistics compiled by the Deutsche Bundesbank can also be accessed at: Reproduction permitted only if source is stated. www.bundesbank.de/statisticalpublications ISSN 2190–8990 A publication schedule for selected statistics can be viewed on the following page: Finalised on 8 October 2019. www.bundesbank.de/statisticalcalender Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics October 2019 3 Contents I. Euro area and exchange rate stability convergence criterion 1. Euro area countries and irrevoc able euro conversion rates in the third stage of Economic and Monetary Union .................................................................. 7 2. Central rates and intervention rates in Exchange Rate Mechanism II ............................... 7 II. Euro foreign exchange reference rates of the European Central Bank 1. Daily rates . 8 2. Monthly averages ..................................................................... 12 3. End-of-year rates and annual averages ..................................................... 15 4. Exchange rates of major currencies (chart) .................................................. 17 III. Effective exchange rates of the euro 1. Annual and monthly averages ........................................................... -

The Moldovan Leu Recent Developments and Assessment of the Equilibrium Exchange Rate

Policy Briefing Series [PB/10/2015] The Moldovan Leu Recent developments and assessment of the equilibrium exchange rate Enzo Weber, Jörg Radeke, Matthias Lücke German Economic Team Moldova Berlin/Chisinau, November 2015 German Economic Team Moldova Background and objective Background . Regional developments and worsening of domestic conditions in Moldova affected foreign exchange flows and in turn the exchange rate of the Moldovan Leu throughout 2014 and 2015 Objective of this policy briefing . Estimation of the equilibrium exchange rate in order to assess if the market rate is in line with underlying fundamentals German Economic Team Moldova 2 Structure Part 1: Recent developments affecting the exchange rate Part 2: Assessment of the equilibrium exchange rate Part 3: Conclusions and policy implications German Economic Team Moldova 3 1. Recent developments affecting the exchange rate Exchange rate and official reserves MDL/USD 3.0 USD bn 22 19 2.5 16 13 2.0 10 1.5 7 International Reserves (lhs) Exchange rate (rhs) Source: National Bank of Moldova . Moldovan Leu: gradual depreciation trend against the US dollar visible since 2013 . Depreciation accelerated during second half of 2014 turning into exchange rate crisis during mid of January and mid of February 2015 . Moldovan exchange rate crisis triggered by lack of confidence due to bank fraud, political uncertainty after elections and currency crises in Ukraine and Russia . In addition, signs of panic and speculation showed . National Bank raised interest rates, intervened in foreign exchange market, thus successfully stabilising the exchange rate and quenching panic and speculative attacks German Economic Team Moldova 4 i. Bilateral exchange rates against the USD 120 Index, Jan. -

Moldova RISK & COMPLIANCE REPORT DATE: March 2018

Moldova RISK & COMPLIANCE REPORT DATE: March 2018 KNOWYOURCOUNTRY.COM Executive Summary - Moldova Sanctions: None FAFT list of AML No Deficient Countries Not on EU White list equivalent jurisdictions Higher Risk Areas: Corruption Index (Transparency International & W.G.I.) Failed States Index (Political Issues)(Average Score) Non - Compliance with FATF 40 + 9 Recommendations Medium Risk Areas: US Dept of State Money Laundering Assessment Weakness in Government Legislation to combat Money Laundering World Governance Indicators (Average Score) Major Investment Areas: Agriculture - products: vegetables, fruits, grapes, grain, sugar beets, sunflower seed, tobacco; beef, milk; wine Industries: sugar, vegetable oil, food processing, agricultural machinery; foundry equipment, refrigerators and freezers, washing machines; hosiery, shoes, textiles Exports - commodities: foodstuffs, textiles, machinery Exports - partners: Russia 20.9%, Romania 19.8%, Italy 11.6%, Ukraine 6.6%, Turkey 6%, Germany 4.7% (2012) Imports - commodities: mineral products and fuel, machinery and equipment, chemicals, textiles Investment Restrictions: There are no economic or industrial strategies that have a discriminatory effect on foreign- owned investors in Moldova, and no limits on foreign ownership or control, except in the 1 right to purchase and sell agricultural and forest land, which is restricted to Moldovan citizens. The Law on Entrepreneurship and Enterprises has a list of activities restricted solely to state enterprises, which includes, among others, human -

Republic of Moldova Economic Review of Thetransnistria Region Public Disclosure Authorized

Report No. 17886-MD Republic of Moldova Economic Review of theTransnistria Region Public Disclosure Authorized June 1998 Europe and Central Asia Region Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized ] i t Public Disclosure Authorized Currency Equivalents Lei TR- Transnistria Ruble (local currency of the Transnistria region) 1995 (annual average) 1996 (annual average) US$1.00 = Lei 4.49 US$1.00 = Lei 4.60 US$1.00 = TR 61,300 US$1.00 = TR 410,083 1997 (annual average) January 1998 US$1.00 = Lei 4.62 US$1.00 = Lei 4.71 US$1.00 = TR 650,417 US$1.00 = TR 680,000 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS CIS Commonwealth of Independent States ECA Europe and Central Asia Region FSU Former Soviet Union GDP Gross domestic product GOM Government of Moldova NBM National Bank of Moldova OGRF Military contingent of the Russian Federation in Transnistria OSCE Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe PREM Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Unit at ECA PRM Parliament of the Republic of Moldova SME Small and medium-size enterprises TDS Transnistrian Department of Statistics TRB Transnistrian Republican Bank TSS Transnistrian Supreme Soviet (regional Parliament) FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 Vice President Johannes Linn, ECAVP Country Director Roger Grawe, ECCO7 Sector Leader Hafez Ghanem. ECSPE Responsible Staff James Parks, Resident Representative, ECCMD Elena Nikulina,Economist, ECCMD REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA: ECONOMIC REVIEW OF THE TRANSNISTRIA REGION TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY i CHAPTER I. BACKGROUND 1 A. History 1 B. Territory 2 C. Population 2 D. Economic Importance of the Transnistria Region in Soviet Times 3 E.