The Asean Charter: Asean Failure Or Member Failure?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

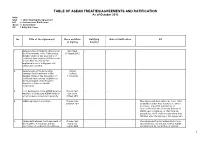

Table of Asean Treaties/Agreements And

TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. Title of the Agreement Place and Date Ratifying Date of Ratification EIF of Signing Country 1. Memorandum of Understanding among Siem Reap - - - the Governments of the Participating 29 August 2012 Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on the Second Pilot Project for the Implementation of a Regional Self- Certification System 2. Memorandum of Understanding Phuket - - - between the Government of the Thailand Member States of the Association of 6 July 2012 Southeast Asian nations (ASEAN) and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on Health Cooperation 3. Joint Declaration of the ASEAN Defence Phnom Penh - - - Ministers on Enhancing ASEAN Unity for Cambodia a Harmonised and Secure Community 29 May 2012 4. ASEAN Agreement on Custom Phnom Penh - - - This Agreement shall enter into force, after 30 March 2012 all Member States have notified or, where necessary, deposited instruments of ratifications with the Secretary General of ASEAN upon completion of their internal procedures, which shall not take more than 180 days after the signing of this Agreement 5. Agreement between the Government of Phnom Penh - - - The Agreement has not entered into force the Republic of Indonesia and the Cambodia since Indonesia has not yet notified ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations 2 April 2012 Secretariat of its completion of internal 1 TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. -

Asean Charter

THE ASEAN CHARTER THE ASEAN CHARTER Association of Southeast Asian Nations The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was established on 8 August 1967. The Member States of the Association are Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam. The ASEAN Secretariat is based in Jakarta, Indonesia. =or inquiries, contact: Public Affairs Office The ASEAN Secretariat 70A Jalan Sisingamangaraja Jakarta 12110 Indonesia Phone : (62 21) 724-3372, 726-2991 =ax : (62 21) 739-8234, 724-3504 E-mail: [email protected] General information on ASEAN appears on-line at the ASEAN Website: www.asean.org Catalogue-in-Publication Data The ASEAN Charter Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat, January 2008 ii, 54p, 10.5 x 15 cm. 341.3759 1. ASEAN - Organisation 2. ASEAN - Treaties - Charter ISBN 978-979-3496-62-7 =irst published: December 2007 1st Reprint: January 2008 Printed in Indonesia The text of this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted with proper acknowledgment. Copyright ASEAN Secretariat 2008 All rights reserved CHARTER O THE ASSOCIATION O SOUTHEAST ASIAN NATIONS PREAMBLE WE, THE PEOPLES of the Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), as represented by the Heads of State or Government of Brunei Darussalam, the Kingdom of Cambodia, the Republic of Indonesia, the Lao Peoples Democratic Republic, Malaysia, the Union of Myanmar, the Republic of the Philippines, the Republic of Singapore, the Kingdom of Thailand and the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam: NOTING -

ASEAN 2030 Toward a Borderless Economic Community ASEAN 2030 Toward a Borderless Economic Community

ASEAN 2030 Toward a Borderless Economic Community ASEAN 2030 Toward a Borderless Economic Community Asian Development Bank Institute © 2014 Asian Development Bank Institute All rights reserved. Published 2014. Printed in Japan. Printed using vegetable oil-based inks on recycled paper; manufactured through a totally chlorine-free process. ISBN 978-4-89974-051-3 (Print) ISBN 978-4-89974-052-0 (PDF) The views in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI), its Advisory Council, ADB’s Board of Governors, or the governments of ADB members. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” or other geographical names in this publication, ADBI does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Users are restricted from reselling, redistributing, or creating derivative works without the express, written consent of ADBI. Asian Development Bank Institute Kasumigaseki Building 8F 3-2-5, Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku Tokyo 100-6008, Japan www.adbi.org Contents List of Boxes, Figures, and Tables v Foreword ix Acknowledgments xi About the Study xiii Abbreviations xv Executive Summary xix Chapter 1: ASEAN Today 1 1.1 Evolution of Economic Cooperation 4 1.2 Global and Regional Economic Context 11 1.3 Progress of the ASEAN Economic Community -

The Struggle of Becoming the 11Th Member State of ASEAN: Timor Leste‘S Case

The Struggle of Becoming the 11th Member State of ASEAN: Timor Leste‘s Case Rr. Mutiara Windraskinasih, Arie Afriansyah 1 1 Faculty of Law, Universitas Indonesia E-mail : [email protected] Submitted : 2018-02-01 | Accepted : 2018-04-17 Abstract: In March 4, 2011, Timor Leste applied for membership in ASEAN through formal application conveying said intent. This is an intriguing case, as Timor Leste, is a Southeast Asian country that applied for ASEAN Membership after the shift of ASEAN to acknowledge ASEAN Charter as its constituent instrument. Therefore, this research paper aims to provide a descriptive overview upon the requisites of becoming ASEAN Member State under the prevailing regulations. The substantive requirements of Timor Leste to become the eleventh ASEAN Member State are also surveyed in the hopes that it will provide a comprehensive understanding as why Timor Leste has not been accepted into ASEAN. Through this, it is to be noted how the membership system in ASEAN will develop its own existence as a regional organization. This research begins with a brief introduction about ASEAN‘s rules on membership admission followed by the practice of ASEAN with regard to membership admission and then a discussion about the effort of Timor Leste to become one of ASEAN member states. Keywords: membership, ASEAN charter, timor leste, law of international and regional organization I. INTRODUCTION South East Asia countries outside the The 1967 Bangkok Conference founding father states to join ASEAN who produced the Declaration of Bangkok, which wish to bind to the aims, principles and led to the establishment of ASEAN in August purposes of ASEAN. -

The Rise and Decline of the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM)

LES CAHIERS EUROPEENS DE SCIENCES PO. > N° 04/2006 The Rise and Decline of the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM) Assymmetric Bilateralism and the Limitations of Interregionalism > David Camroux D. Camroux – The Rise and Decline of the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM) Les Cahiers européens de Sciences Po. n° 04/2006 DAVID CAMROUX The Rise and Decline of the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM): Assymmetric Bilateralism and the Limitations of Interregionalism1 David Camroux is Senior Research Associate at CERI-Sciences Po. Citation : David Camroux (2006), “The Rise and Decline of the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM): Assymmetric Bilateralism and the Limitations of Interregionalism”, Les Cahiers européens de Sciences Po, n° 04. 1 This is a significantly revised and much updated version of a previous article « Contemporary EU-East Asian Relations : An Assessment of the ASEM Process » in R.K. Jain (ed.) The European Union in a Changing World, New Delhi, Radiant Publishers, 2002, pp. 142-165. One of the problems in the analysis of ASEM is that many of the observers, including this author, are also participants, albeit minor ones, in the process by dint of their involvement in ASEM’s two track activities. This engenders both a problem of maintaining a critical distance and, also, an understandable tendency to give value to an object of research, in which one has invested so much time and energy and which provides so many opportunities for travel and networking between Europe and Asia. Such is the creative tension within which observers of ASEM are required to function Les Cahiers européens de Sciences Po. – n° 04/2006 Abstract East Asia’s economic dynamism attracted the attention of European political leaders in the 1980s leading to the publication of Asian strategy papers by most European governments. -

ASEAN' S Constitutionalization of International Law: Challenges to Evolution Under the New ASEAN Charter*

ASEAN' S Constitutionalization of International Law: Challenges to Evolution Under the New ASEAN Charter* DIANE A. DESIERTO** This Article discusses the normative trajectory of in- ternational obligations assumed by Southeast Asian countries (particularlythe Organizational Purposes that mandate compliance with international treaties, human rights and democraticfreedoms), and the inev- itable emergence of a body of discrete "ASEAN Law" arisingfrom the combined legislative functions of the ASEAN Summit and the ASEAN Political, Economic and Social Communities. I discuss several immediate and short-term challenges from the increased consti- tutionalization of international obligations, such as: 1) the problem of incorporation (or lack of direct ef- fect) and the remaining dependence of some Southeast Asian states on their respective constitutionalmecha- nisms to transform internationalobligations into bind- ing constitutional or statutory obligations; 2) the problem of hybridity and normative transplantation, which I illustrate in the interpretive issues regarding the final text of the ASEAN Comprehensive Investment Agreement, which draws some provisions from GATT 1994 and contains language similar to the U.S. and * Paper admitted for presentation at the "Non-State Actors" panel of the International Law Association (I.L.A.), British Branch Conference on Compliance, Oxford Brookes University, April 15-16, 2010. I gratefully acknowledge helpful research assistance from Johanna Aleria Lorenzo of the University of the Philippines (U.P.) College of Law and valuable exchanges on preliminary drafts with Alexander Aizenstatd, Andreas Th. Milller and Lorenz Langer. ** Law Reform Specialist and Professorial Lecturer, U.P. Institute of International Legal Studies, U.P. College of Law and Lyceum of the Philippines College of Law; J.S.D. -

ASEAN Charter

CHARTER OF THE ASSOCIATION OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN NATIONS PREAMBLE WE, THE PEOPLES of the Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), as represented by the Heads of State or Government of Brunei Darussalam, the Kingdom of Cambodia, the Republic of Indonesia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Malaysia, the Union of Myanmar, the Republic of the Philippines, the Republic of Singapore, the Kingdom of Thailand and the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam: NOTING with satisfaction the significant achievements and expansion of ASEAN since its establishment in Bangkok through the promulgation of The ASEAN Declaration; RECALLING the decisions to establish an ASEAN Charter in the Vientiane Action Programme, the Kuala Lumpur Declaration on the Establishment of the ASEAN Charter and the Cebu Declaration on the Blueprint of the ASEAN Charter; MINDFUL of the existence of mutual interests and interdependence among the peoples and Member States of ASEAN which are bound by geography, common objectives and shared destiny; INSPIRED by and united under One Vision, One Identity and One Caring and Sharing Community; UNITED by a common desire and collective will to live in a region of lasting peace, security and stability, sustained economic growth, shared prosperity and social progress, and to promote our vital interests, ideals and aspirations; RESPECTING the fundamental importance of amity and cooperation, and the principles of sovereignty, equality, territorial integrity, non-interference, consensus and unity in diversity; ADHERING to -

Charter of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations

CHARTER OF THE ASSOCIATION OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN NATIONS PREAMBLE WE, THE PEOPLES of the Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), as represented by the Heads of State or Government of Brunei Darussalam, the Kingdom of Cambodia, the Republic of Indonesia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Malaysia, the Union of Myanmar, the Republic of the Philippines, the Republic of Singapore, the Kingdom of Thailand and the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam: NOTING with satisfaction the significant achievements and expansion of ASEAN since its establishment in Bangkok through the promulgation of The ASEAN Declaration; RECALLING the decisions to establish an ASEAN Charter in the Vientiane Action Programme, the Kuala Lumpur Declaration on the Establishment of the ASEAN Charter and the Cebu Declaration on the Blueprint of the ASEAN Charter; MINDFUL of the existence of mutual interests and interdependence among the peoples and Member States of ASEAN which are bound by geography, common objectives and shared destiny; INSPIRED by and united under One Vision, One Identity and One Caring and Sharing Community; UNITED by a common desire and collective will to live in a region of lasting peace, security and stability, sustained economic growth, shared prosperity and social progress, and to promote our vital interests, ideals and aspirations; RESPECTING the fundamental importance of amity and cooperation, and the principles of sovereignty, equality, territorial integrity, non-interference, consensus and unity in diversity; ADHERING to -

Is Asean Still Relevant

CICP E-BOOK No. 1 ASEAN SECURITY AND ITS RELEVENCY Leng Thearith June 2009 Phnom Penh, Cambodia Table of Contents Chapter I: Discussion of “Criteria of Relevance” and the term “Regionalism” .. 1 1. Research Question ............................................................................................... 1 2. Criteria of Relevance ........................................................................................... 2 3. Discussion of the Term “Regionalism” ............................................................... 2 3.1. Classification of Regionalism ...................................................................... 3 3.2. Functions of Regionalism ............................................................................ 5 4. Chapter Breakdown ............................................................................................. 6 Chapter II: ASEAN’s Relevance Since Its Establishment until 1989 ................... 8 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 8 1. ASEAN‟s Relevance at Its Creation ................................................................... 8 1.1. The Association of Southeast Asia (ASA) ................................................ 12 1.2. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) ........................... 13 2. ASEAN‟s Relevance since Its Establishment till 1989 ..................................... 16 2.1. Definitions of “traditional security” and “non-traditional security”.......... 16 2.2. -

The EU's Group-To-Group Dialogue with The

EUC Working Paper No. 14 Working Paper No. 18, December 2013 The EU's Group-to-Group Dialogue with the Southern Mediterranean and ASEAN – How much have they achieved? A Comparative Analysis Dr Hong Wai Mun Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Humboldt University of Berlin Illustration: European Union (1997) ABSTRACT Four decades of the EU's group-to-group dialogues with the Southern Mediterranean grouping of countries and with ASEAN have produced different dynamics and outcomes, despite the EU’s common strategy to use economic soft power to achieve their goals for the partnerships. Diverging conditions in the two regions created inconsistency in the EU's application of the common approach. The EU's neighbourhood security concerns forced it to relax its political stand with their Southern Mediterranean partners. For ASEAN, geographical distance dilutes the EU’s security concerns it that region and has afforded the EU to be more ideological and assertive on democracy and human rights practices. These issues have provoked disagreements in EU-ASEAN dialogues, but both sides have also tried to remain pragmatic in order to achieve some progress in the partnership. In contrast, the protracted the Arab-Israeli conflict continues to hamper the Euro-Mediterranean dialogue, resulting in little progress. Social upheavals in the Southern Mediterranean also brought their partnership to a standstill. The EU's cooperation with former authoritarian regimes like Libya and Syria have only caused damage to its credibility in the Southern Mediterranean, and future Euro-Mediterranean dialogues are likely to be affected by it. The EU Centre in Singapore is a partnership of 13 EUC Working Paper No. -

IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS EU – ASEAN: Challenges Ahead

DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR EXTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS EU – ASEAN: Challenges ahead Author: Laurence VANDEWALLE Abstract The EU and ASEAN are both regional organisations created to manage countries' interdependence and answer regional security challenges. While the two have different histories and integration processes, they correlate as natural partners, with cooperation on integration the core of their relationship. The EU supports ASEAN not only financially but also through exchanges and projects aimed at sharing experiences and expertise. In light of the global shift towards Asia, relations with ASEAN are particularly important for the EU. The Union is seeking to increase dialogue and cooperation with ASEAN, as well as to pursue closer coordination on regional and international issues. The European Parliament can play a role in this by deepening the inter-parliamentary aspect of the relationship and scrutinising EU agreements negotiated with countries in the region. DG EXPO/B/PolDep/Note/2014_214 PE.536.426 December 2014 EN Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies This paper is an initiative of the Policy Department, DG EXPO AUTHORS: Laurence VANDEWALLE with contributions from Chiara DE SANTIS (intern) This paper contains extracts from Marika ARMANOVICA, ‘The ASEAN Inter-parliamentary assembly’, Policy Department, DG EXPO, November 2013. Directorate-General for External Policies of the Union Policy Department SQM 03 Y 064 Rue Wiertz 60 BE-1047 Brussels Editorial Assistant: Aysegul UNAL CONTACT: Feedback of all kinds is welcome. Please write to: [email protected]. To obtain paper copies, please send a request by e-mail to: [email protected]. -

ASEAN–ADB Cooperation Toward the Asean Community: Advancing Integration and Sustainable Development in Southeast Asia

ASEAN–ADB Cooperation toward the ASEAN Community Advancing Integration and Sustainable Development in Southeast Asia For the past 5 decades, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) have both supported poverty reduction, sustainable development, and regional cooperation and integration in Southeast Asia. This publication provides an overview of cooperation between ADB ASEAN–ADB COOPERATION and ASEAN, and how it has contributed to a more connected, competitive, and integrated region. Moving forward, the ASEAN–ADB partnership will continue to support greater development and prosperity in Southeast Asia to enhance the lives of all the region’s people. TOWARD THE ASEAN COMMUNITY Advancing Integration and Sustainable About the Asian Development Bank Development in Southeast Asia ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to the majority of the world’s poor. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by 67 members, including 48 from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines www.adb.org ASEAN–ADB COOPERATION TOWARD THE ASEAN COMMUNITY Advancing Integration and Sustainable Development in Southeast Asia April 2016 Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2016 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 4444; Fax +63 2 636 2444 www.adb.org; openaccess.adb.org [email protected]; [email protected] Some rights reserved.