The EU's Group-To-Group Dialogue with The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lao PDR's Way Into the ASEAN Single Market

Lao PDR’s Way into the ASEAN Single Market The ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) ‘AEC 2015’ – what does it mean? Towards the ASEAN Community: ASEAN has been founded in The year 2015 marks the formal establishment of the AEC. 1967, the ASEAN Free Trade Area has been established in 1992 ‘Launching the AEC’ is a major milestone that will allow ASEAN and Lao PDR became a member in 1997. The ASEAN integration to foster a common identity and create momentum for further process intensified since 2003: at the 9th ASEAN Summit, ASEAN economic integration, relying on strong regional frameworks. Member States (AMS) decided to establish the ASEAN communi- Declaring the AEC operational, however, is not the final culmina- ty, which includes the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), the tion of the ASEAN economic integration process: ASEAN integra- ASEAN Political-Security Community (ASPSC), and the ASEAN tion is an on-going, dynamic process that will continue beyond Socio-Cultural Community (ASCC). 2015, as emphasized in the new AEC Blueprint 2025. The ASEAN Economic Community (AEC): The AEC will be estab- Progress and Achievements in the Implemen- lished in 2015. The ASEAN Leaders adopted the AEC Blueprint at tation of the AEC the 13th ASEAN Summit in 2007 in Singapore, to serve as a coher- ent master plan guiding the establishment of the AEC. The AEC ASEAN has endorsed 3 main agreements in order to create the Blueprint 2015 envisions four pillars for economic integration: Single Market: the ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA) in 2010, the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Services (AFAS) in 1. -

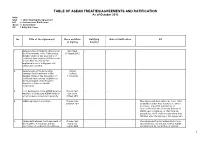

Table of Asean Treaties/Agreements And

TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. Title of the Agreement Place and Date Ratifying Date of Ratification EIF of Signing Country 1. Memorandum of Understanding among Siem Reap - - - the Governments of the Participating 29 August 2012 Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on the Second Pilot Project for the Implementation of a Regional Self- Certification System 2. Memorandum of Understanding Phuket - - - between the Government of the Thailand Member States of the Association of 6 July 2012 Southeast Asian nations (ASEAN) and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on Health Cooperation 3. Joint Declaration of the ASEAN Defence Phnom Penh - - - Ministers on Enhancing ASEAN Unity for Cambodia a Harmonised and Secure Community 29 May 2012 4. ASEAN Agreement on Custom Phnom Penh - - - This Agreement shall enter into force, after 30 March 2012 all Member States have notified or, where necessary, deposited instruments of ratifications with the Secretary General of ASEAN upon completion of their internal procedures, which shall not take more than 180 days after the signing of this Agreement 5. Agreement between the Government of Phnom Penh - - - The Agreement has not entered into force the Republic of Indonesia and the Cambodia since Indonesia has not yet notified ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations 2 April 2012 Secretariat of its completion of internal 1 TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. -

Asean Charter

THE ASEAN CHARTER THE ASEAN CHARTER Association of Southeast Asian Nations The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was established on 8 August 1967. The Member States of the Association are Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam. The ASEAN Secretariat is based in Jakarta, Indonesia. =or inquiries, contact: Public Affairs Office The ASEAN Secretariat 70A Jalan Sisingamangaraja Jakarta 12110 Indonesia Phone : (62 21) 724-3372, 726-2991 =ax : (62 21) 739-8234, 724-3504 E-mail: [email protected] General information on ASEAN appears on-line at the ASEAN Website: www.asean.org Catalogue-in-Publication Data The ASEAN Charter Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat, January 2008 ii, 54p, 10.5 x 15 cm. 341.3759 1. ASEAN - Organisation 2. ASEAN - Treaties - Charter ISBN 978-979-3496-62-7 =irst published: December 2007 1st Reprint: January 2008 Printed in Indonesia The text of this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted with proper acknowledgment. Copyright ASEAN Secretariat 2008 All rights reserved CHARTER O THE ASSOCIATION O SOUTHEAST ASIAN NATIONS PREAMBLE WE, THE PEOPLES of the Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), as represented by the Heads of State or Government of Brunei Darussalam, the Kingdom of Cambodia, the Republic of Indonesia, the Lao Peoples Democratic Republic, Malaysia, the Union of Myanmar, the Republic of the Philippines, the Republic of Singapore, the Kingdom of Thailand and the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam: NOTING -

ASEAN 2030 Toward a Borderless Economic Community ASEAN 2030 Toward a Borderless Economic Community

ASEAN 2030 Toward a Borderless Economic Community ASEAN 2030 Toward a Borderless Economic Community Asian Development Bank Institute © 2014 Asian Development Bank Institute All rights reserved. Published 2014. Printed in Japan. Printed using vegetable oil-based inks on recycled paper; manufactured through a totally chlorine-free process. ISBN 978-4-89974-051-3 (Print) ISBN 978-4-89974-052-0 (PDF) The views in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI), its Advisory Council, ADB’s Board of Governors, or the governments of ADB members. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” or other geographical names in this publication, ADBI does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Users are restricted from reselling, redistributing, or creating derivative works without the express, written consent of ADBI. Asian Development Bank Institute Kasumigaseki Building 8F 3-2-5, Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku Tokyo 100-6008, Japan www.adbi.org Contents List of Boxes, Figures, and Tables v Foreword ix Acknowledgments xi About the Study xiii Abbreviations xv Executive Summary xix Chapter 1: ASEAN Today 1 1.1 Evolution of Economic Cooperation 4 1.2 Global and Regional Economic Context 11 1.3 Progress of the ASEAN Economic Community -

4 at the 34'^^ ASEAN Summit Earlier This Year, Our Leaders Reiterated

STATEMENT ON BEHALF OF THE ASSOCIATION OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN NATIONS BY AMBASSADOR BURHAN GAFOOR, PERMANENT REPRESENTATIVE OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE TO THE UNITED NATIONS, AT THE THEMATIC DEBATE ON CLUSTER FIVE: OTHER DISARMAMENT MEASURES AND INTERNATIONAL SECURITY, FIRST COMMITTEE, 29 OCTOBER 2019 Thank you, Mr Chairman. 1 I have the honour to deliver this statement on behalf of the Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations(ASEAN). Our statement will focus on cybersecurity, on which I will make three points. 2 First, ASEAN's vision is for a peaceful, secure, and resilient cyberspace, which serves as an enabler of economic progress, enhanced regional connectivity and the betterment of living standards for all. Digital transformation will have tremendous benefits and opportunities for our region. At the same time, we are cognisant that pervasive, ever-evolving, and transboundary cyber threats have the potential to undemiine international peace and security. To this end, ASEAN believes that cybersecurity requires coordinated expertise from multiple stakeholders from across different domains, to effectively mitigate threats, build trust, and realise the benefits of technology. 3 Second, no govemment can deal with the growing sophistication and transboundary nature of cyber threats alone. Regional collaboration is imperative, and ASEAN has taken concrete and practical steps to this end. 4 At the 34'^^ ASEAN Summit earlier this year, our Leaders reiterated ASEAN's commitment to enhancing cybersecurity cooperation, and the building of an open, secure, stable, accessible, and resilient cyberspace supporting the digital economy of the ASEAN region. At the 3^^^ ASEAN Ministerial Conference on Cybersecurity(AMCC) in September 2018, ASEAN became the first and only regional group to subscribe to the 11 voluntaiy, non-binding norms recommended in the 2015 report of the UN Group of Governmental Experts on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security (UNGGE). -

The Struggle of Becoming the 11Th Member State of ASEAN: Timor Leste‘S Case

The Struggle of Becoming the 11th Member State of ASEAN: Timor Leste‘s Case Rr. Mutiara Windraskinasih, Arie Afriansyah 1 1 Faculty of Law, Universitas Indonesia E-mail : [email protected] Submitted : 2018-02-01 | Accepted : 2018-04-17 Abstract: In March 4, 2011, Timor Leste applied for membership in ASEAN through formal application conveying said intent. This is an intriguing case, as Timor Leste, is a Southeast Asian country that applied for ASEAN Membership after the shift of ASEAN to acknowledge ASEAN Charter as its constituent instrument. Therefore, this research paper aims to provide a descriptive overview upon the requisites of becoming ASEAN Member State under the prevailing regulations. The substantive requirements of Timor Leste to become the eleventh ASEAN Member State are also surveyed in the hopes that it will provide a comprehensive understanding as why Timor Leste has not been accepted into ASEAN. Through this, it is to be noted how the membership system in ASEAN will develop its own existence as a regional organization. This research begins with a brief introduction about ASEAN‘s rules on membership admission followed by the practice of ASEAN with regard to membership admission and then a discussion about the effort of Timor Leste to become one of ASEAN member states. Keywords: membership, ASEAN charter, timor leste, law of international and regional organization I. INTRODUCTION South East Asia countries outside the The 1967 Bangkok Conference founding father states to join ASEAN who produced the Declaration of Bangkok, which wish to bind to the aims, principles and led to the establishment of ASEAN in August purposes of ASEAN. -

ASEAN's Pattaya Problem by Donald K Emmerson

ASEAN's Pattaya problem By Donald K Emmerson The turmoil in Thailand is about domestic questions: who shall rule the kingdom, and what is the future of democracy there? But the crisis also raises questions for the larger region: who will lead the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and what is the future of democracy in Southeast Asia? In mid-2008, Thailand began its tenure as ASEAN's chair. The chair is expected, at a minimum, to host successfully the association's main events, most notably the ASEAN summit and multiple other summits between Southeast Asia's leaders and those of other countries. Accordingly, Thailand had planned to welcome the heads of ASEAN's other nine member government plus their counterparts from Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea in a series of meetings in the Thai resort town of Pattaya on April 10-12. (The other nine are Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Myanmar, Laos, Brunei, Cambodia and Indonesia.) Summitry called for decorum - serene images of Thai leaders greeting their distinguished guests. Bedlam came closer to describing the scene in Pattaya when Thai protesters opposed to the new government of Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva stormed the summit's venue and forced its cancellation. Heads of state and government who had already arrived at the seaside resort 150 kilometers southeast of Bangkok were evacuated by helicopter. Planes carrying other leaders to Thailand were turned back in mid-flight. No one blames ASEAN for Thailand's political travails. Because of it, however, the regional organization has lost major face. -

MODEL ASEAN MEETING: a GUIDEBOOK UNDERSTANDING ASEAN PROCESSES and MECHANISMS Model ASEAN Meeting: a Guidebook Copyright 2020

MODEL ASEAN MEETING: A GUIDEBOOK UNDERSTANDING ASEAN PROCESSES AND MECHANISMS Model ASEAN Meeting: A Guidebook Copyright 2020 ASEAN Foundation The ASEAN Secretariat Heritage Building 1st Floor Jl. Sisingamangaraja No. 70 Jakarta Selatan - 12110 Indonesia Phone: +62-21-3192-4833 Fax.: +62-21-3192-6078 E-mail: [email protected] General information on the ASEAN Foundation appears online at the ASEAN Foundation http://modelasean.aseanfoundation.org/ ASEAN Foundation Part of this publication may be quoted for the purpose of promoting ASEAN through the Model ASEAN Meeting activity provided that proper acknowledgement is given. Photo Credits: The ASEAN Foundation Published by the ASEAN Foundation, Jakarta, Indonesia. All rights reserved. The Model ASEAN Meeting is supported by the U.S. Government through the ASEAN - U.S. PROGRESS (Partnership for Good Governance, Equitable and Sustainable Development and Security). MODEL ASEAN MEETING: A GUIDEBOOK UNDERSTANDING ASEAN PROCESSES AND MECHANISMS Model ASEAN Meeting: A Guidebook FOREWORD The ASEAN Foundation Model ASEAN Meeting (AFMAM) is a unique platform that not only enables youth to learn about ASEAN and its decision-making process effectively through an authentic learning environment, but also encourages the creation of a peaceful commu- nity and tolerance towards different value and cultural background. Through AFMAM, we also wanted to produce a cohort of ASEAN youth that has the capabilities to create and run their own Model ASEAN Meeting (MAM) at their own universities, initiating a ripple effect that helps spread MAM movement across the region. One of the key instruments to achieve these objectives is the AFMAM Guidebook. First created in 2016, the AFMAM Guidebook plays an important role in outlining the mecha- nisms and structures in ASEAN that can be used as a reference for delegates to implement activities and have a broader understanding of ASEAN affairs. -

The Rise and Decline of the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM)

LES CAHIERS EUROPEENS DE SCIENCES PO. > N° 04/2006 The Rise and Decline of the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM) Assymmetric Bilateralism and the Limitations of Interregionalism > David Camroux D. Camroux – The Rise and Decline of the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM) Les Cahiers européens de Sciences Po. n° 04/2006 DAVID CAMROUX The Rise and Decline of the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM): Assymmetric Bilateralism and the Limitations of Interregionalism1 David Camroux is Senior Research Associate at CERI-Sciences Po. Citation : David Camroux (2006), “The Rise and Decline of the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM): Assymmetric Bilateralism and the Limitations of Interregionalism”, Les Cahiers européens de Sciences Po, n° 04. 1 This is a significantly revised and much updated version of a previous article « Contemporary EU-East Asian Relations : An Assessment of the ASEM Process » in R.K. Jain (ed.) The European Union in a Changing World, New Delhi, Radiant Publishers, 2002, pp. 142-165. One of the problems in the analysis of ASEM is that many of the observers, including this author, are also participants, albeit minor ones, in the process by dint of their involvement in ASEM’s two track activities. This engenders both a problem of maintaining a critical distance and, also, an understandable tendency to give value to an object of research, in which one has invested so much time and energy and which provides so many opportunities for travel and networking between Europe and Asia. Such is the creative tension within which observers of ASEM are required to function Les Cahiers européens de Sciences Po. – n° 04/2006 Abstract East Asia’s economic dynamism attracted the attention of European political leaders in the 1980s leading to the publication of Asian strategy papers by most European governments. -

East Asia Summit Documents Series, 2005-2014

East Asia Summit Documents Series 2005 Summit Documents Series Asia - 2014 East East Asia Summit Documents Series 2005-2014 www.asean.org ASEAN one vision @ASEAN one identity one community East Asia Summit (EAS) Documents Series 2005-2014 ASEAN Secretariat Jakarta The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was established on 8 August 1967. The Member States of the Association are Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam. The ASEAN Secretariat is based in Jakarta, Indonesia. For inquiries, contact: The ASEAN Secretariat Public Outreach and Civil Society Division 70A Jalan Sisingamangaraja Jakarta 12110 Indonesia Phone : (62 21) 724-3372, 726-2991 Fax : (62 21) 739-8234, 724-3504 E-mail : [email protected] Catalogue-in-Publication Data East Asia Summit (EAS) Documents Series 2005-2014 Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat, May 2015 327.59 1. A SEAN – East Asia 2. Declaration – Statement ISBN 978-602-0980-18-8 General information on ASEAN appears online at the ASEAN Website: www.asean.org The text of this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, provided proper acknowledgement is given and a copy containing the reprinted material is sent to Public Outreach and Civil Society Division of the ASEAN Secretariat, Jakarta Copyright Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) 2015. All rights reserved 2 (DVW$VLD6XPPLW'RFXPHQWV6HULHV East Asia Summit Documents Series 2005-2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS (Summit and Ministerial Levels Documents) 2005 Summit Chairman’s Statement of the First East Asia Summit, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 14 December 2005 .................................................................................... 9 Kuala Lumpur Declaration on the East Asia Summit, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 14 December 2005 ................................................................................... -

Don't Make Us Choose: Southeast Asia in the Throes of US-China Rivalry

THE NEW GEOPOLITICS OCTOBER 2019 ASIA DON’T MAKE US CHOOSE Southeast Asia in the throes of US-China rivalry JONATHAN STROMSETH DON’T MAKE US CHOOSE Southeast Asia in the throes of US-China rivalry JONATHAN STROMSETH EXECUTIVE SUMMARY U.S.-China rivalry has intensified significantly in Southeast Asia over the past year. This report chronicles the unfolding drama as it stretched across the major Asian summits in late 2018, the Second Belt and Road Forum in April 2019, the Shangri-La Dialogue in May-June, and the 34th summit of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in August. Focusing especially on geoeconomic aspects of U.S.-China competition, the report investigates the contending strategic visions of Washington and Beijing and closely examines the region’s response. In particular, it examines regional reactions to the Trump administration’s Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) strategy. FOIP singles out China for pursuing regional hegemony, says Beijing is leveraging “predatory economics” to coerce other nations, and poses a clear choice between “free” and “repressive” visions of world order in the Indo-Pacific region. China also presents a binary choice to Southeast Asia and almost certainly aims to create a sphere of influence through economic statecraft and military modernization. Many Southeast Asians are deeply worried about this possibility. Yet, what they are currently talking about isn’t China’s rising influence in the region, which they see as an inexorable trend that needs to be managed carefully, but the hard-edged rhetoric of the Trump administration that is casting the perception of a choice, even if that may not be the intent. -

Chapter 2: the Machinery of ASEAN

CHAPTER TWO THE MACHINERY OF ASEAN 2.1 Currently there are nine members in ASEAN - Brunei, Burma, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. ASEAN began with five members in 1967 - Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand. To this group, Burnei was added in 1984, Vietnam in 1995 and Burma and Laos in 1997. 2.2 ASEAN is a complex network of organisations. The 'alphabet soup' of acronyms is bewildering to anyone who approaches ASEAN for the first time. The following information about the structure and operation of ASEAN has been provided by the ASEAN secretariat via its Internet site1 and the submission provided by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. 2.3 All member states of ASEAN must be represented at all meetings as befits its consensus decision making style and debate can be lengthy and inconclusive. Given the number and extent of the meeting schedule, the expansion of ASEAN to include Vietnam, Myanmar and Laos is likely to be demanding on the resources of these new members and to exacerbate the difficulties of the organisation in achieving consensus. ASEAN has already modified its process to one of 'flexible consensus' in anticipation of this.2 ASEAN Heads of Government 2.4 The ASEAN Summit is the meeting of the ASEAN Heads of Government. These are now annual meetings but initially they were infrequent. The first summit was in 1976, the second in 1977 (the 10th anniversary), the third in 1987 (the 20th anniversary). In 1992, the fourth, in Singapore decided that the ASEAN Heads of Government would meet formally every three years and informally at least once in between to lay down directions and initiatives for ASEAN activities.