My Retrospective on ASEAN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lao PDR's Way Into the ASEAN Single Market

Lao PDR’s Way into the ASEAN Single Market The ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) ‘AEC 2015’ – what does it mean? Towards the ASEAN Community: ASEAN has been founded in The year 2015 marks the formal establishment of the AEC. 1967, the ASEAN Free Trade Area has been established in 1992 ‘Launching the AEC’ is a major milestone that will allow ASEAN and Lao PDR became a member in 1997. The ASEAN integration to foster a common identity and create momentum for further process intensified since 2003: at the 9th ASEAN Summit, ASEAN economic integration, relying on strong regional frameworks. Member States (AMS) decided to establish the ASEAN communi- Declaring the AEC operational, however, is not the final culmina- ty, which includes the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), the tion of the ASEAN economic integration process: ASEAN integra- ASEAN Political-Security Community (ASPSC), and the ASEAN tion is an on-going, dynamic process that will continue beyond Socio-Cultural Community (ASCC). 2015, as emphasized in the new AEC Blueprint 2025. The ASEAN Economic Community (AEC): The AEC will be estab- Progress and Achievements in the Implemen- lished in 2015. The ASEAN Leaders adopted the AEC Blueprint at tation of the AEC the 13th ASEAN Summit in 2007 in Singapore, to serve as a coher- ent master plan guiding the establishment of the AEC. The AEC ASEAN has endorsed 3 main agreements in order to create the Blueprint 2015 envisions four pillars for economic integration: Single Market: the ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA) in 2010, the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Services (AFAS) in 1. -

People Power II in the Philippines: the First E-Revolution?

People Power II in the Philippines: The First E-Revolution? Julius Court With the new Century over a year old, technology has now played critical yet very different roles in bringing two of the world’s leaders to power. Among others things, Florida will remembered for technological hitches that plagued the ballot counting and possibly pushed the outcome of the U.S. election in favor of George W. Bush. On the other hand, a new information and communications technology (ICT) - the mobile phone - was the symbol of the People Power II revolution in the Philippines. Arguably, the most lasting image of Ms Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo’s new Presidency was when, on being asked in a news conference whether a Lt. Gen. Espinosa was planning a coup, she called him up on her mobile phone. In moment of high drama she asked him directly if this was the case and after a brief conversation reported it wasn’t. But it was the use of cellphones for “texting” rather than calls that was the most intriguing part of People Power II and was also the key to its success. The lack of attention to the role of technology is surprising. People Power II was arguably the world’s first “E-revolution” - a change of government brought about by new forms of ICTs. “Texting” allowed information on former President Estrada’s corruption to be shared widely. It helped facilitate the protests at the EDSA shrine at a speed that was startling - it took only 88 hours after the collapse of impeachment to remove Estrada. -

Typhoon Haiyan

Emergency appeal Philippines: Typhoon Haiyan Emergency appeal n° MDRPH014 GLIDE n° TC-2013-000139-PHL 12 November 2013 This emergency appeal is launched on a preliminary basis for CHF 72,323,259 (about USD 78,600,372 or EUR 58,649,153) seeking cash, kind or services to cover the immediate needs of the people affected and support the Philippine Red Cross in delivering humanitarian assistance to 100,000 families (500,000 people) within 18 months. This includes CHF 761,688 to support its role in shelter cluster coordination. The IFRC is also soliciting support from National Societies in the deployment of emergency response units (ERUs) at an estimated value of CHF 3.5 million. The operation will be completed by the end of June 2015 and a final report will be made available by 30 September 2015, three months after the end Red Cross staff and volunteers were deployed as soon as safety conditions allowed, of the operation. to assess conditions and ensure that those affected by Typhoon Haiyan receive much-needed aid. Photo: Philippine Red Cross CHF 475,495 was allocated from the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) on 8 November 2013 to support the National Society in undertaking delivering immediate assistance to affected people and undertaking needs assessments. Un-earmarked funds to replenish DREF are encouraged. Summary Typhoon Haiyan (locally known as Yolanda) made landfall on 8 November 2013 with maximum sustained winds of 235 kph and gusts of up to 275 kph. The typhoon and subsequent storm surges have resulted in extensive damage to infrastructure, making access a challenge. -

The Rise to Power of Philippine President Joseph Estrada

International Bulletin of Political Psychology Volume 5 Issue 3 Article 1 7-17-1998 From the Movies to Malacañang: The Rise to Power of Philippine President Joseph Estrada IBPP Editor [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/ibpp Part of the International Relations Commons, Leadership Studies Commons, and the Other Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Editor, IBPP (1998) "From the Movies to Malacañang: The Rise to Power of Philippine President Joseph Estrada," International Bulletin of Political Psychology: Vol. 5 : Iss. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://commons.erau.edu/ibpp/vol5/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Bulletin of Political Psychology by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Editor: From the Movies to Malacañang: The Rise to Power of Philippine President Joseph Estrada International Bulletin of Political Psychology Title: From the Movies to Malacañang: The Rise to Power of Philippine President Joseph Estrada Author: Elizabeth J. Macapagal Volume: 5 Issue: 3 Date: 1998-07-17 Keywords: Elections, Estrada, Personality, Philippines Abstract. This article was written by Ma. Elizabeth J. Macapagal of Ateneo de Manila University, Republic of the Philippines. She brings at least three sources of expertise to her topic: formal training in the social sciences, a political intuition for the telling detail, and experiential/observational acumen and tradition as the granddaughter of former Philippine president, Diosdado Macapagal. (The article has undergone minor editing by IBPP). -

Asean Charter

THE ASEAN CHARTER THE ASEAN CHARTER Association of Southeast Asian Nations The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was established on 8 August 1967. The Member States of the Association are Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam. The ASEAN Secretariat is based in Jakarta, Indonesia. =or inquiries, contact: Public Affairs Office The ASEAN Secretariat 70A Jalan Sisingamangaraja Jakarta 12110 Indonesia Phone : (62 21) 724-3372, 726-2991 =ax : (62 21) 739-8234, 724-3504 E-mail: [email protected] General information on ASEAN appears on-line at the ASEAN Website: www.asean.org Catalogue-in-Publication Data The ASEAN Charter Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat, January 2008 ii, 54p, 10.5 x 15 cm. 341.3759 1. ASEAN - Organisation 2. ASEAN - Treaties - Charter ISBN 978-979-3496-62-7 =irst published: December 2007 1st Reprint: January 2008 Printed in Indonesia The text of this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted with proper acknowledgment. Copyright ASEAN Secretariat 2008 All rights reserved CHARTER O THE ASSOCIATION O SOUTHEAST ASIAN NATIONS PREAMBLE WE, THE PEOPLES of the Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), as represented by the Heads of State or Government of Brunei Darussalam, the Kingdom of Cambodia, the Republic of Indonesia, the Lao Peoples Democratic Republic, Malaysia, the Union of Myanmar, the Republic of the Philippines, the Republic of Singapore, the Kingdom of Thailand and the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam: NOTING -

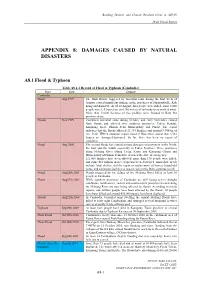

Appendix 8: Damages Caused by Natural Disasters

Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Draft Finnal Report APPENDIX 8: DAMAGES CAUSED BY NATURAL DISASTERS A8.1 Flood & Typhoon Table A8.1.1 Record of Flood & Typhoon (Cambodia) Place Date Damage Cambodia Flood Aug 1999 The flash floods, triggered by torrential rains during the first week of August, caused significant damage in the provinces of Sihanoukville, Koh Kong and Kam Pot. As of 10 August, four people were killed, some 8,000 people were left homeless, and 200 meters of railroads were washed away. More than 12,000 hectares of rice paddies were flooded in Kam Pot province alone. Floods Nov 1999 Continued torrential rains during October and early November caused flash floods and affected five southern provinces: Takeo, Kandal, Kampong Speu, Phnom Penh Municipality and Pursat. The report indicates that the floods affected 21,334 families and around 9,900 ha of rice field. IFRC's situation report dated 9 November stated that 3,561 houses are damaged/destroyed. So far, there has been no report of casualties. Flood Aug 2000 The second floods has caused serious damages on provinces in the North, the East and the South, especially in Takeo Province. Three provinces along Mekong River (Stung Treng, Kratie and Kompong Cham) and Municipality of Phnom Penh have declared the state of emergency. 121,000 families have been affected, more than 170 people were killed, and some $10 million in rice crops has been destroyed. Immediate needs include food, shelter, and the repair or replacement of homes, household items, and sanitation facilities as water levels in the Delta continue to fall. -

4 at the 34'^^ ASEAN Summit Earlier This Year, Our Leaders Reiterated

STATEMENT ON BEHALF OF THE ASSOCIATION OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN NATIONS BY AMBASSADOR BURHAN GAFOOR, PERMANENT REPRESENTATIVE OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE TO THE UNITED NATIONS, AT THE THEMATIC DEBATE ON CLUSTER FIVE: OTHER DISARMAMENT MEASURES AND INTERNATIONAL SECURITY, FIRST COMMITTEE, 29 OCTOBER 2019 Thank you, Mr Chairman. 1 I have the honour to deliver this statement on behalf of the Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations(ASEAN). Our statement will focus on cybersecurity, on which I will make three points. 2 First, ASEAN's vision is for a peaceful, secure, and resilient cyberspace, which serves as an enabler of economic progress, enhanced regional connectivity and the betterment of living standards for all. Digital transformation will have tremendous benefits and opportunities for our region. At the same time, we are cognisant that pervasive, ever-evolving, and transboundary cyber threats have the potential to undemiine international peace and security. To this end, ASEAN believes that cybersecurity requires coordinated expertise from multiple stakeholders from across different domains, to effectively mitigate threats, build trust, and realise the benefits of technology. 3 Second, no govemment can deal with the growing sophistication and transboundary nature of cyber threats alone. Regional collaboration is imperative, and ASEAN has taken concrete and practical steps to this end. 4 At the 34'^^ ASEAN Summit earlier this year, our Leaders reiterated ASEAN's commitment to enhancing cybersecurity cooperation, and the building of an open, secure, stable, accessible, and resilient cyberspace supporting the digital economy of the ASEAN region. At the 3^^^ ASEAN Ministerial Conference on Cybersecurity(AMCC) in September 2018, ASEAN became the first and only regional group to subscribe to the 11 voluntaiy, non-binding norms recommended in the 2015 report of the UN Group of Governmental Experts on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security (UNGGE). -

The Struggle of Becoming the 11Th Member State of ASEAN: Timor Leste‘S Case

The Struggle of Becoming the 11th Member State of ASEAN: Timor Leste‘s Case Rr. Mutiara Windraskinasih, Arie Afriansyah 1 1 Faculty of Law, Universitas Indonesia E-mail : [email protected] Submitted : 2018-02-01 | Accepted : 2018-04-17 Abstract: In March 4, 2011, Timor Leste applied for membership in ASEAN through formal application conveying said intent. This is an intriguing case, as Timor Leste, is a Southeast Asian country that applied for ASEAN Membership after the shift of ASEAN to acknowledge ASEAN Charter as its constituent instrument. Therefore, this research paper aims to provide a descriptive overview upon the requisites of becoming ASEAN Member State under the prevailing regulations. The substantive requirements of Timor Leste to become the eleventh ASEAN Member State are also surveyed in the hopes that it will provide a comprehensive understanding as why Timor Leste has not been accepted into ASEAN. Through this, it is to be noted how the membership system in ASEAN will develop its own existence as a regional organization. This research begins with a brief introduction about ASEAN‘s rules on membership admission followed by the practice of ASEAN with regard to membership admission and then a discussion about the effort of Timor Leste to become one of ASEAN member states. Keywords: membership, ASEAN charter, timor leste, law of international and regional organization I. INTRODUCTION South East Asia countries outside the The 1967 Bangkok Conference founding father states to join ASEAN who produced the Declaration of Bangkok, which wish to bind to the aims, principles and led to the establishment of ASEAN in August purposes of ASEAN. -

ASEAN's Pattaya Problem by Donald K Emmerson

ASEAN's Pattaya problem By Donald K Emmerson The turmoil in Thailand is about domestic questions: who shall rule the kingdom, and what is the future of democracy there? But the crisis also raises questions for the larger region: who will lead the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and what is the future of democracy in Southeast Asia? In mid-2008, Thailand began its tenure as ASEAN's chair. The chair is expected, at a minimum, to host successfully the association's main events, most notably the ASEAN summit and multiple other summits between Southeast Asia's leaders and those of other countries. Accordingly, Thailand had planned to welcome the heads of ASEAN's other nine member government plus their counterparts from Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea in a series of meetings in the Thai resort town of Pattaya on April 10-12. (The other nine are Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Myanmar, Laos, Brunei, Cambodia and Indonesia.) Summitry called for decorum - serene images of Thai leaders greeting their distinguished guests. Bedlam came closer to describing the scene in Pattaya when Thai protesters opposed to the new government of Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva stormed the summit's venue and forced its cancellation. Heads of state and government who had already arrived at the seaside resort 150 kilometers southeast of Bangkok were evacuated by helicopter. Planes carrying other leaders to Thailand were turned back in mid-flight. No one blames ASEAN for Thailand's political travails. Because of it, however, the regional organization has lost major face. -

2013 Major Water-Related Disasters in the World (Pt.1)

2013 Major Water-Related Disasters in the World (Pt.1) India. Nepal (Jun. 2013) Bangladesh (May. 2013) China (May. 2013) China (Aug. 2013) China (Aug. 2013) The Torrential rain by early Landed tropical cyclone Continuous heavy Continuous heavy rain caused The torrential rain by coming monsoon caused MAHASEN brought rain caused floods over-flow the river of border Typhoon Utor, hit China on floods, flash floods and torrential rain and storms. and landslide in area between China and Russia, Aug. 14, caused floods in landslides in northern India and The death toll was 17., and south China. and floods in Northeast China southern China. More than 8 Nepal. The Death toll was about 1.5 million people 55 were killed. and Far East Russia. The death million were affected and 88 6,054 across India, 76 in Nepal were affected. toll was 118 in China. were killed. India (Oct. 2013) The Tropical Cyclone PHAILIN China, Taiwan (Jul. 2013) landed at east coast of India, China (Jan. 2013) Torrential rain caused and killed 47 people. About 1.3 A landslide caused floods and landslides in million people were affected. by the continuous China. And Typhoon heavy rains buried SOULIK lashed Taiwan 16 families, killing India (Oct. 2013) and coastal area of China 46.* th The Flash floods in Odisha on 13 Jul. These killed and Andhra Pradesh, east 233. coast of India, killed 72 people. China, Viet Nam (Sep.2013) The rainstorm by Typhoon Saudi Arabia (Apr.2013) WUTIP caused floods and Continuous heavy rain for 2 Viet Nam (Nov.2013) killed 16 in Viet Nam and 74 weeks caused floods and The torrential rain by Tropical in China. -

MODEL ASEAN MEETING: a GUIDEBOOK UNDERSTANDING ASEAN PROCESSES and MECHANISMS Model ASEAN Meeting: a Guidebook Copyright 2020

MODEL ASEAN MEETING: A GUIDEBOOK UNDERSTANDING ASEAN PROCESSES AND MECHANISMS Model ASEAN Meeting: A Guidebook Copyright 2020 ASEAN Foundation The ASEAN Secretariat Heritage Building 1st Floor Jl. Sisingamangaraja No. 70 Jakarta Selatan - 12110 Indonesia Phone: +62-21-3192-4833 Fax.: +62-21-3192-6078 E-mail: [email protected] General information on the ASEAN Foundation appears online at the ASEAN Foundation http://modelasean.aseanfoundation.org/ ASEAN Foundation Part of this publication may be quoted for the purpose of promoting ASEAN through the Model ASEAN Meeting activity provided that proper acknowledgement is given. Photo Credits: The ASEAN Foundation Published by the ASEAN Foundation, Jakarta, Indonesia. All rights reserved. The Model ASEAN Meeting is supported by the U.S. Government through the ASEAN - U.S. PROGRESS (Partnership for Good Governance, Equitable and Sustainable Development and Security). MODEL ASEAN MEETING: A GUIDEBOOK UNDERSTANDING ASEAN PROCESSES AND MECHANISMS Model ASEAN Meeting: A Guidebook FOREWORD The ASEAN Foundation Model ASEAN Meeting (AFMAM) is a unique platform that not only enables youth to learn about ASEAN and its decision-making process effectively through an authentic learning environment, but also encourages the creation of a peaceful commu- nity and tolerance towards different value and cultural background. Through AFMAM, we also wanted to produce a cohort of ASEAN youth that has the capabilities to create and run their own Model ASEAN Meeting (MAM) at their own universities, initiating a ripple effect that helps spread MAM movement across the region. One of the key instruments to achieve these objectives is the AFMAM Guidebook. First created in 2016, the AFMAM Guidebook plays an important role in outlining the mecha- nisms and structures in ASEAN that can be used as a reference for delegates to implement activities and have a broader understanding of ASEAN affairs. -

Typhoon Haiyan

Information Bulletin Philippines: Typhoon Haiyan Information bulletin n° 1 7 November 2013 This bulletin is being issued for information only and reflects the current situation and details available at Text box for brief photo caption. Example: In February 2007, the this time. The Philippine Red Cross has placed its disaster response teams on standby for rapid Colombian Red Cross Society distributed urgently needed deployment and preparedness stocks ready for dispatch, if required. materials after the floods and slides in Cochabamba. IFRC (Arial 8/black colour) Summary: Typhoon Haiyan is currently making its way across the Pacific and has intensified into a category 5 typhoon (super typhoon). Forecasts indicate Typhoon Haiyan will make landfall in the Philippines on Friday, 8 November 2013. Known locally as Typhoon Yolanda, Haiyan is expected to track across Samar and Leyte provinces in Eastern Visayas region, packing maximum sustained winds of 240 kph (150 mph). It is expected to bring widespread torrential rain and damaging winds, and trigger life- threatening flash floods, as well as mudslides on higher terrain. The Philippine Red Cross (PRC) has been on highest alert since the Preparedness stocks – which include standard relief items – are being transferred typhoon was sighted. The PRC is from the Philippine Red Cross central warehouse in Manila to a regional maintaining close coordination with warehouse in Cebu for immediate dispatch to areas where they will be needed. disaster authorities and has alerted Photo: Joe Cropp/IFRC all its chapters in Visayas (Central, Eastern and Western Visayas) as well as in Bicol, Mindoro, and Caraga regions for immediate response, if required.