Hawickborders Mill Towns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Soils Round Jedburgh and Morebattle

DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOR SCOTLAND MEMOIRS OF THE SOIL SURVEY OF GREAT BRITAIN SCOTLAND THE SOILS OF THE COUNTRY ROUND JEDBURGH & MOREBATTLE [SHEETS 17 & 181 BY J. W. MUIR, B.Sc.(Agric.), A.R.I.C., N.D.A., N.D.D. The Macaulay Institute for Soil Research ED INB URGH HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE '956 Crown copyright reserved Published by HER MAJESTY’SSTATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased from 13~Castle Street, Edinburgh 2 York House, Kingsway, Lond6n w.c.2 423 Oxford Street, London W.I P.O. Box 569, London S.E. I 109 St. Mary Street, Cardiff 39 King Street, Manchester 2 . Tower Lane, Bristol I 2 Edmund Street, Birmingham 3 80 Chichester Street, Belfast or through any bookseller Price &I 10s. od. net. Printed in Great Britain under the authority of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Text and half-tone plates printed by Pickering & Inglis Ltd., Glasgow. Colour inset printed by Pillans & Ylson Ltd., Edinburgh. PREFACE The soils of the country round Jedburgh and Morebattle (Sheets 17 and 18) were surveyed during the years 1949-53. The principal surveyors were Mr. J. W. Muir (1949-52), Mr. M. J. Mulcahy (1952) and Mr. J. M. Ragg (1953). The memoir has been written and edited by Mr. Muir. Various members of staff of the Macaulay Institute for Soil Research have contributed to this memoir; Dr. R. L. Mitchell wrote the section on Trace Elements, Dr. R. Hart the section on Minerals in Fine Sand Fractions, Dr. R. C. Mackenzie and Mr. W. A. Mitchell the section on Minerals in Clay Fractions and Mr. -

SP Notice of Poll and Situation of Polling Stations

Scottish Parliamentary election – constituency contest Midlothian South, Tweeddale & Lauderdale Constituency Statement of Persons Nominated and Notice of Poll A poll will be held on 6 May 2021 between 7am and 10 pm The following people have been or stand nominated for election as a member of the Scottish Parliament for the above constituency. Those who no longer stand nominated are listed, but will have a comment in the right hand column. If candidate no longer nominated, reason Name of candidate Description of candidate (if any) why Dominic Ashmole Scottish Green Party Michael James Banks Vanguard Party Christine Grahame Scottish National Party (SNP) Shona Haslam Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party AC May Scottish Liberal Democrats Scottish Labour Party and Scottish Katherine Sangster Co-operative Party Printed and published by Netta Meadows, Constituency Returning Officer, Council Headquarters, Newtown St. Boswells, Melrose, TD6 0SA 31 March 2021 Scottish Parliamentary Constituency election: Midlothian South, Tweeddale & Lauderdale Constituency Situation of Polling Stations No. of Situation of polling station Description of persons entitled to polling vote station 1 Carlops Village Centre, Carlops, EH26 9FF 1A Whole Register 2 Graham Institute, Lower Green, West Linton, EH46 7EW 1B 1 – 946 3 Graham Institute, Lower Green, West Linton, EH46 7EW 1B 948 – 1836 4 Newlands Centre, Romanno Bridge, EH46 7BZ 1C Whole Register 5 Eddleston Village Hall, Eddleston, peebles, EH45 8QP 1D Whole Register 6 Skirling Village Hall, Skirling, Biggar, ML12 6HD 1E Whole Register 7 Stobo Village Hall, Stobo, Peebles, EH45 8NX 1F Whole Register 8 Broughton Village Hall, Main Street, Broughton, ML12 6HQ 1G Whole Register 9 Tweedsmuir Village Hall, Tweedsmuir, Biggar, ML12 6QN 1H Whole Register 10 Manor Village Hall, Kirkton Manor, Peebles. -

The Galashiels and Selkirk Almanac and Directory for 1898

UMBRELLAS Re-Covered in One Hour from 1/9 Upwards. All Kinds of Repairs Promptly Executed at J. R. FULTON'S Umbrella Ware- house, 51 HIGH STREET, Galashiels. *%\ TWENTIETH YEAR OF ISSUE. j?St masr Ok Galasbiels and Selkirk %•* Almanac and Directorp IFOIR, X898 Contains a Variety of Useful information, County Lists for Roxburgh and Selkirk, Local Institutions, and a Complete Trade Directory. Price, - - One Penny. PUBLISHED BY JOH3ST ZMZCQ-CTiEiE] INT, Proprietor of the "Scottish Border Record," LETTERPRESS and LITHOGRAPHIC PRINTER, 25 Channel Street, Galashiels. ADVERTISEMENT. NEW MODEL OF THE People's Cottage Piano —^~~t» fj i «y <kj»~ — PATERSON & SONS would draw Special Attention to this New Model, which is undoubtedly the Cheapest and Best Cottage Piano ever offered, and not only A CHEAP PIANO, but a Thoroughly Reliable Instrument, with P. & Sons' Guakantee. On the Hire System at 21s per Month till paid up. Descriptive Price-Lists on Application, or sent Free by Post. A Large Selection of Slightly-used Instruments returned from Hire will be Sold at Great Reductions. Sole Agents for the Steinway and Bechstein Pianofortes, the two Greatest Makers of the present century. Catalogues on Application. PATEESON <Sc SONS, Musicsellers to the Queen, 27 George Street, EDINBURGH. PATERSON & SONS' Tuners visit the Principal Districts of Scotland Quarterly, and can give every information as to the Purchase or Exchanne of Pianofortes. Orders left with John McQueen, "Border Record" Office, Galashiels, shall receive prompt attention. A life V'C WELLINGTON KNIFE POLISH. 1 *™ KKL f W % Prepared for Oakey's Knife-Boards and all Patent Knife- UfgWa^^""Kmm ^"it— I U Clea-iing Machines. -

Scottish Borders & the English Lake District

scotland.nordicvisitor.com SCOTTISH BORDERS & THE ENGLISH LAKE DISTRICT ITINERARY DAY 1 DAY 1: EDINBURGH, CAPITAL OF SCOTLAND Welcome to Edinburgh. For an easy and comfortable way to get from Edinburgh Airport to your hotel in the city centre, we are happy to arrange a private transfer for you (optional, at additional cost). After settling in, go out and explore the city. Edinburgh has a long and storied history, so there’s no shortage of UNESCO World Heritage Sites, museums and landmarks to visit. A stroll along the bustling Princes Street, with views over the gardens to the Edinburgh Castle, also makes a nice introduction to the city centre. Spend the night in Edinburgh. Attractions: Edinburgh DAY 2 DAY 2: CROSSING THE BORDER TO ENGLAND‘S LAKE DISTRICT Head for the scenic Scottish Borders area today with its charming old villages and gently rolling hills. On the way you can visit Glenkinchie Distillery and taste its 12-year-old single malt whisky, which was named Best Lowland Single Malt in the 2013 World Whiskies Awards. For a great photo opportunity, don‘t miss a stop at the scenic Scott‘s View, one of the best known lookouts in the southern Scotland! Another suggestion is to visit the area‘s historical abbeys. Perhaps the most famous is the St Mary’s Abbey, also called Melrose Abbey, a partly ruined monastery of the Cistercian order, the first of its kind in Scotland. The ruins make for a hauntingly beautiful sight, especially with moody clouds hanging low overhead. We also recommend a visit to Abbotsford House, the ancestral home of Sir Walter Scott, the famous 19th century novelist and poet, beautifully located on the banks of the River Tweed. -

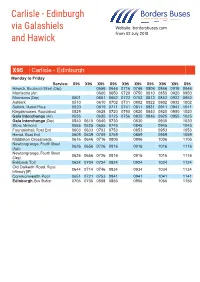

Carlisle - Edinburgh Via Galashiels Website: Bordersbuses.Com and Hawick from 02 July 2018

Carlisle - Edinburgh via Galashiels Website: bordersbuses.com and Hawick From 02 July 2018 X95 Carlisle - Edinburgh Monday to Friday Service: X95 X95 X95 X95 X95 X95 X95 X95 X95 X95 Hawick, Buccleuch Street (Dep) 0556 0646 0716 0746 0806 0846 0916 0946 Morrisons (Arr) 0600 0650 0720 0750 0810 0850 0920 0950 Morrisons (Dep) 0501 0601 0652 0722 0752 0812 0852 0922 0952 Ashkirk 0510 0610 0702 0731 0802 0822 0902 0932 1002 Selkirk, Market Place 0520 0619 0711 0741 0811 0831 0911 0941 1011 Kingsknowes, Roundabout 0529 0628 0720 0750 0820 0840 0920 0950 1020 Gala Interchange (Arr) 0535 0635 0725 0756 0825 0846 0925 0955 1025 Gala Interchange (Dep) 0540 0610 0640 0730 0830 0930 1030 Stow, Memorial 0555 0625 0655 0745 0845 0945 1045 Fountainhall, Road End 0603 0633 0703 0753 0853 0953 1053 Heriot, Road End 0609 0639 0709 0759 0859 0959 1059 Middleton Crossroads 0616 0646 0716 0806 0906 1006 1106 Newtongrange, Fourth Street 0626 0656 0726 0816 0916 1016 1116 (App) Newtongrange, Fourth Street 0626 0656 0726 0816 0916 1016 1116 (Dep) Eskbank Toll 0634 0704 0734 0824 0924 1024 1124 Old Dalkeith Road, Royal 0644 0714 0746 0834 0934 1034 1134 Infirmary [IF] Commonwealth Pool 0651 0721 0753 0841 0941 1041 1141 Edinburgh, Bus Station 0706 0736 0808 0856 0956 1056 1156 X95 Carlisle - Edinburgh Monday to Friday Service:Service: X95X95 X95X95 X95X95 X95X95 X95X95 X95X95 X95X95 X95X95 X95X95 X95X95 HawickCarlisle, Buccleuch, English St, Street The Courts(Dep) [A] 0855 05560955 0646 07161055 0746 08061155 0846 09161255 0946 MorrisonsKingstown (Arr) Road , -

The Snoot, Roberton, Hawick

The Snoot, Roberton, Hawick Viewing is essential to appreciate this substantial detached two storey property located in a rural location with lovely surrounding views. The building itself has much historical significance. Built as a presbyterian church in 1843, the building was then used as a youth hostel. In recent years it was home to acclaimed guitarist John Renbourn. In need of renovation, the property offers an abundance of possibilities and currently offers ground floor accommodation with a mezzanine level, and small garden to the side. • LARGE LIVING SPACE • OPEN PLAN KITCHEN DINING AREA • SHOWER ROOM • WC • MEZZANINE LEVEL • GARDEN • STUNNING VIEWS • EPC RATING G • OFFERS IN THE REGION OF £85,000 28 High Street, Hawick TD9 9BY T. 0800 1300 353 F. 01450 378 525 E. [email protected] The Town Known for many years as The Queen of the Borders, and situated at the confluence of the Rivers Slitrig and Teviot, Hawick is the largest of the Border towns. Frequent winners of national floral awards, and famous world-wide for its quality knitwear, Hawick is part of The Cashmere Trail and is the major centre for the industry in the Borders. There is a large range of major supermarkets in Sainsburys and Morrisons, a very recently re-built Lidl, an Aldi in construction, and a large Iceland and Farmfoods. A Homebase and Argos are also beneficial to the town, along with a large leisure centre facility for families and kids alike, with many other sports facilities throughout the town. Hawick boasts the award winning Wilton Lodge Park which lies on the River Teviot, and is currently enjoying a £3 million pound regeneration, which includes a new cafeteria and footbridge, together with a new external 3G sports pitch and tennis courts. -

Borders Family History Society Sales List February 2021

Borders Family History Society www.bordersfhs.org.uk Sales List February 2021 Berwickshire Roxburghshire Census Transcriptions 2 Census Transcriptions 8 Death Records 3 Death Records 9 Monumental Inscriptions 4 Monumental Inscriptions 10 Parish Records 5 Parish Records 11 Dumfriesshire Poor Law Records 11 Parish Records 5 Prison Records 11 Edinburghshire/Scottish Borders Selkirkshire Census Transcriptions 5 Census Transcriptions 12 Death Records 5 Death Records 12 Monumental Inscriptions 5 Monumental Inscriptions 13 Peeblesshire Parish Records 13 Census Transcriptions 6 Prison Records 13 Death Records 7 Other Publications 14 Monumental Inscriptions 7 Maps 17 Parish Records 7 Past Magazines 17 Prison Records 7 Postage Rates 18 Parish Map Diagrams 19 Borders FHS Monumental Inscriptions are recorded by a team of volunteer members of the Society and are compiled over several visits to ensure accuracy in the detail recorded. Additional information such as Militia Lists, Hearth Tax, transcriptions of Rolls of Honour and War Memorials are included. Wherever possible, other records are researched to provide insights into the lives of the families who lived in the Parish. Society members may receive a discount of £1.00 per BFHS monumental inscription volume. All publications can be ordered through: online : via the Contacts page on our website www.bordersfhs.org.uk/BFHSContacts.asp by selecting Contact type 'Order for Publications'. Sales Convenor, Borders Family History Society, 52 Overhaugh St, Galashiels, TD1 1DP, mail to : Scotland Postage, payment, and ordering information is available on page 17 NB Please note that many of the Census Transcriptions are on special offer and in many cases, we have only one copy of each for sale. -

Woodland Building Plot, Timberholme, Bedrule, Near Denholm

Hastings Property Shop 28 The Square Kelso TD5 7HH Telephone 01573 225999 Illustration WOODLAND BUILDING PLOT, TIMBERHOLME, BEDRULE, NEAR DENHOLM A Generous Woodland Plot with Full Planning Consent for Stylish House and Garage in Tucked Away Location Near The Village of Denholm in the Scottish Borders OFFERS AROUND £85,000 www.hastingslegal.co.uk BUILDING PLOT, TIMBERHOLME, BEDRULE, NEAR DENHOLM Prime location building plot extending to approximately ½ an acre with PRICE AND MARKETING POLICY full planning consent for a detached house and garage providing an ideal Offers around £85,000 are invited and should be submitted to the Selling opportunity for a buyer looking to self build in an attractive rural yet Agents, Hastings Property Shop, 28 The Square, Kelso, TD5 7HH, 01573 accessible location. This generous plot lies in a woodland setting on outskirts 225999, Fax 01573 229888. The seller reserves the right to sell at any time of Bedrule in a unique sheltered setting with stunning countryside. and interested parties will be expected to provide the Selling Agents with advice on the source of funds with suitable confirmation of their ability to LOCATION finance the purchase. The plot enjoys a sheltered location in the lee of Ruberslaw approximately a mile south of Bedrule and 3 miles from the much sought after village of Denholm located off the road from Bedrule to Bonchester Bridge. The area is renowned for its beauty with open countryside and excellent walking country on your doorstep. Denholm Village lies a few miles away and has good facilities including a much acclaimed primary school, a superb 18 hole golf course at Minto, good local shops and services and secondary schooling, main supermarkets and larger shops and facilities nearby at Hawick or Jedburgh about 8 miles distant. -

Kirkhouse TRAQUAIR • PEEBLESSHIRE

Kirkhouse TRAQUAIR • PEEBLESSHIRE Kirkhouse TRAQUAIR • PEEBLESSHIRE EH44 6PU An exceptional country house with lovely countryside views Reception hall • 3 reception rooms • 7 bedrooms 3 bathrooms • Study • Family kitchen • Pantry Utility room • Conservatory Self-contained annexe • 2 bedrooms • Large kitchen Conservatory • Sitting room • Bathroom 5 acres of beautiful gardens • Hard tennis court Greenhouse • Vegetable garden Grazing paddocks • Stabling consisting of 3 timber loose boxes Tack room • Hay store • Burn running through all paddocks Traditional range of outbuildings • Garaging Sheds • Summer house In all about 8.25 acres For sale as a whole Innerleithen 2 miles • Peebles 7 miles • Edinburgh 30 miles (Distances approximate) These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text. Historical Note Dating from the mid-18th century and with later additions, Kirkhouse was in the ownership of The Buccleuch Estate until 1902, when it was bought by Charles Tennant, Lord Glenconner. During the mid-20th century, Kirkhouse was occupied by Sir James Dundas, who is believed to have been responsible for much of the ornamental tree planting. Situation Kirkhouse is situated on the edge of Traquair, a beautiful and peaceful rural location with stunning views of the surrounding countryside. Approximately 7 miles south east of the historic Burgh and market town of Peebles and 2 miles from Innerleithen, both towns provide a full range of local shops and services including very good primary and secondary schools. Edinburgh with its international airport, is within easy commuting distance, approximately 30 miles to the north. -

Innerleithen

INTRODUCTION | CHALLENGES | VISION, AIMS AND SPATIAL STRATEGY POLICIES | APPENDICES | SETTLEMENTS SETTLEMENT PROFILE INNERLEITHEN This profile should be read in conjunction with the relevant settlement map. DESCRIPTION Innerleithen is located in the Western Development Area as defined in the Strategic Development Plan. The town is located in the Northern Housing Market Area. Innerleithen is located almost 7 miles east of Peebles. The 2001 Census population was 2619. PLACE MAKING CONSIDERATIONS Innerleithen sits on a significant bend in the River Tweed at a point where the valley floor opens out into wide haughland, and the majority of the built up area of the town lies on this haughland. The entrances into the town are generally quite pleasing and there is a good integration with the adjoining landscape to the north due to the mature landscape framework. The River Tweed and the flood plain dominate the southern side of the village. The town developed in the late 18th century on the development of the textile industry and the publication in the early 19th century of Sir Walter Scott’s St Ronan’s Wells, which extolled the restorative qualities of the spring waters. At this time the High Street was developed but it was not until the end of that century that the major expansion of the settlement occurred extending behind the High Street to the south and to the south east beyond the Leithen Water. Another major expansion also occurred after the 2nd World War with a major public housing scheme in the east towards the former Pirn House. Recently new residential development within the settlement has taken place to the north in the vicinity of Kirklands and it is in this area where future development is expected to take place. -

Scottish Borders Walking Festival: Innerleithen, Walkerburn And

Name Scottish BordersNo Date Walking GradeFestival:Distance Innerleithen,Ascent WalkerburnTime and ClovenfordsWalk Led 2013 by Requirements Description List of Walks (including duration transport time) Robert Mathison 1.1 Sunday 1st Harder 11¾ miles / 1770 feet / 9:20 - 17:10 7:30 Alastair Learmont and Full hill walking gear From Traquair Kirk our route takes us westwards up the Glen to Glenshiel Banks (minor road/farm tracks). By Walk 19 km 540 metres Kitty Bruce-Gardyne of and a packed lunch moorland track we climb southwards to Blackhouse Forest, and thence by forest tracks to Blackhouse Tower. We Learmont MacKenzie return to Traquair Kirk along the Southern Upland Way. This walk ties in with Alastair Learmont’s talk on “Robert Travel Mathison and the Innerleithen Alpine Club”. The Glen and 1.2 Sunday 1st Harder 9½ miles / 1560 9:20 - 15:10 5:30 Kevin McKinnon of East Full hill walking gear From Traquair Kirk we enter the beautiful Glen valley with its Baronial house frequented by the royals and the rich and Birkscairn Hill Moderate 15.5 km feet/475 Tweeddale Paths and a packed lunch famous. Past the manmade Loch Eddy, then upwards and onto Birkscairn Hill (a Donald) spectaculer views are gained metres over the Tweed and Traquair Valleys. We then skirt along the ridge before dropping down once more Kirnie Law and 1.3 Sunday 1st Moderate 8 miles / 1800 feet / 10:00 - 15:00 5 Colin Kerr of East Full hill walking gear A steep 150m ascent of Pirn Craig at the start of the walk onwards and upwards to the old mill reservoir on Kirna Law. -

Appraisal Report

Innerleithen Flood Study - Leithen Water & Chapman's Burn Appraisal Report Final Report December 2018 Council Headquarters Newtown St Boswells Melrose Scottish Borders TD6 0SA JBA Project Manager Angus Pettit Unit 2.1 Quantum Court Research Avenue South Heriot Watt Research Park Riccarton Edinburgh EH14 4AP UK Revision History Revision Ref / Date Issued Amendments Issued to S0-P01.01 / 2018 - Angus Pettit S0-P01 Minor amendments S4-P01 / October 2018 - Scottish Borders Council S4-P02 / December 2018 Post-council review and Scottish Borders Council amendments Contract This report describes work commissioned by Duncan Morrison, on behalf of Scottish Borders Council, by a letter dated 16 January 2017. Scottish Borders Council's representative for the contract was Duncan Morrison. Jonathan Garrett, Hannah Otton and Christina Kampanou of JBA Consulting carried out this work. Prepared by .................................................. Jonathan Garrett BEng Engineer Reviewed by ................................................. Angus Pettit BSc MSc CEnv CSci MCIWEM C.WEM Technical Director Purpose This document has been prepared as a Final Report for Scottish Borders Council. JBA Consulting accepts no responsibility or liability for any use that is made of this document other than by the Client for the purposes for which it was originally commissioned and prepared. JBA Consulting has no liability regarding the use of this report except to Scottish Borders Council. Our work has followed accepted procedure in providing the services but given the residual risk associated with any prediction and the variability which can be experienced in flood conditions, we can take no liability for the consequences of flooding in relation to items outside our control or agreed scope of service.