Notes Towards a History of Norfolk Cider

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Council Tax Rates 2020 - 2021

BRECKLAND COUNCIL NOTICE OF SETTING OF COUNCIL TAX Notice is hereby given that on the twenty seventh day of February 2020 Breckland Council, in accordance with Section 30 of the Local Government Finance Act 1992, approved and duly set for the financial year beginning 1st April 2020 and ending on 31st March 2021 the amounts as set out below as the amount of Council Tax for each category of dwelling in the parts of its area listed below. The amounts below for each parish will be the Council Tax payable for the forthcoming year. COUNCIL TAX RATES 2020 - 2021 A B C D E F G H A B C D E F G H NORFOLK COUNTY 944.34 1101.73 1259.12 1416.51 1731.29 2046.07 2360.85 2833.02 KENNINGHALL 1194.35 1393.40 1592.46 1791.52 2189.63 2587.75 2985.86 3583.04 NORFOLK POLICE & LEXHAM 1182.24 1379.28 1576.32 1773.36 2167.44 2561.52 2955.60 3546.72 175.38 204.61 233.84 263.07 321.53 379.99 438.45 526.14 CRIME COMMISSIONER BRECKLAND 62.52 72.94 83.36 93.78 114.62 135.46 156.30 187.56 LITCHAM 1214.50 1416.91 1619.33 1821.75 2226.58 2631.41 3036.25 3643.49 LONGHAM 1229.13 1433.99 1638.84 1843.70 2253.41 2663.12 3072.83 3687.40 ASHILL 1212.28 1414.33 1616.37 1818.42 2222.51 2626.61 3030.70 3636.84 LOPHAM NORTH 1192.57 1391.33 1590.09 1788.85 2186.37 2583.90 2981.42 3577.70 ATTLEBOROUGH 1284.23 1498.27 1712.31 1926.35 2354.42 2782.50 3210.58 3852.69 LOPHAM SOUTH 1197.11 1396.63 1596.15 1795.67 2194.71 2593.74 2992.78 3591.34 BANHAM 1204.41 1405.14 1605.87 1806.61 2208.08 2609.55 3011.01 3613.22 LYNFORD 1182.24 1379.28 1576.32 1773.36 2167.44 2561.52 2955.60 3546.72 -

Contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (Are Distinguished by Letter Code, Given Below) Those from 1801-13 Have Also Been Transcribed and Have No Code

Norfolk Family History Society Norfolk Marriages 1801-1837 The contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (are distinguished by letter code, given below) those from 1801-13 have also been transcribed and have no code. ASt All Saints Hel St. Helen’s MyM St. Mary in the S&J St. Simon & St. And St. Andrew’s Jam St. James’ Marsh Jude Aug St. Augustine’s Jma St. John McC St. Michael Coslany Ste St. Stephen’s Ben St. Benedict’s Maddermarket McP St. Michael at Plea Swi St. Swithen’s JSe St. John Sepulchre McT St. Michael at Thorn Cle St. Clement’s Erh Earlham St. Mary’s Edm St. Edmund’s JTi St. John Timberhill Pau St. Paul’s Etn Eaton St. Andrew’s Eth St. Etheldreda’s Jul St. Julian’s PHu St. Peter Hungate GCo St. George Colegate Law St. Lawrence’s PMa St. Peter Mancroft Hei Heigham St. GTo St. George Mgt St. Margaret’s PpM St. Peter per Bartholomew Tombland MtO St. Martin at Oak Mountergate Lak Lakenham St. John Gil St. Giles’ MtP St. Martin at Palace PSo St. Peter Southgate the Baptist and All Grg St. Gregory’s MyC St. Mary Coslany Sav St. Saviour’s Saints The 25 Suffolk parishes Ashby Burgh Castle (Nfk 1974) Gisleham Kessingland Mutford Barnby Carlton Colville Gorleston (Nfk 1889) Kirkley Oulton Belton (Nfk 1974) Corton Gunton Knettishall Pakefield Blundeston Cove, North Herringfleet Lound Rushmere Bradwell (Nfk 1974) Fritton (Nfk 1974) Hopton (Nfk 1974) Lowestoft Somerleyton The Norfolk parishes 1 Acle 36 Barton Bendish St Andrew 71 Bodham 106 Burlingham St Edmond 141 Colney 2 Alburgh 37 Barton Bendish St Mary 72 Bodney 107 Burlingham -

Norfolk Gardens 2011

Norfolk Gardens 2011 Sponsored by The National Gardens Scheme www.ngs.org.uk NATIONAL GARDENS SCHEME ! BAGTHORPE HALL $ BANK FARM 1 Bagthorpe PE31 6QY. Mr & Mrs D Morton. 3 /2 m N of Fallow Pipe Road, Saddlebow, Kings Lynn PE34 3AS. East Rudham, off A148. At King’s Lynn take A148 to Mr & Mrs Alan Kew. 3m S of Kings Lynn. Turn off Kings Fakenham. At East Rudham (approx 12m) turn L opp The Lynn southern bypass (A47) via slip rd signed St Germans. 1 Crown, 3 /2 m into hamlet of Bagthorpe. Farm buildings on Cross river in Saddlebow village. 1m fork R into Fallow 1 L, wood on R, white gates set back from road, at top of Pipe Rd. Farmhouse /4 m by River Great Ouse. Home- drive. Home-made teas. Adm £3.50, chd free. Sun 20 made teas. Adm £3, chd free. Sun 10 July (11-5). 3 Feb (11-4). /4 -acre windswept garden was created from a field in Snowdrops carpeting woodland walk. 1994. A low maintenance garden of contrasts, filled with f g a b trees, shrubs and newly planted perennials. Many features include large fish pond, small vegetable garden with greenhouse. Splashes of colour from annuals. Walks along the banks of Great Ouse. Dogs on leads. Wood turning demonstration by professional wood turner. Short gravel entrance. Cover garden: Dale Farm, Dereham e f g b Photographer: David M Jones # BANHAMS BARN Browick Road, Wymondham NR18 9RB. Mr C Cooper % 5 BATTERBY GREEN & Mrs J Harden. 1m E of Wymondham. A11 from Hempton, Fakenham NR21 7LY. -

Inmates 4 2012.XLS

Gressenhall Inmates Surname First Names Age Parish Date In Date Out Remarks Minute Book Census Source MH12 Image Abbs Ann 60 Billingford Oct 1836 3 Oct 1836 Abbs James North Elmham Oct 1863 born 27 Jan 1849 26 Oct 1863 1861BC Abbs Eliza North Elmham Sep 1863 14 Sep 1863 Abbs Ethel Lily and children 24 Feb 1908 Abbs OAP 5 Feb 1912 28 Abbs Susan mother of James Feb 1916 28 Abbs Robert died 19 May 1841 8476-642 Abel Arther 9 Nov 1913 To Royal Eastern Counties Inst, 10 Nov 1913 Colchester Abel Gertrude Sarah Gressenhall Sep 1945 08 Oct 1945 Abigail Hariett 11East Dereham Aug 1836 Bastard 15 Aug 1836 Abile Rose 31 Oct 1921 Adcock George 11 East Dereham Jul 1836 Bastard 25 Jul 1836 Adcock Maria 17 16 Oct 1837 Adcock Ann Bawdeswell Nov 1878 15 Jan 1872 20 Nov 1878 Adcock Annie 20 Oct 1914 Adcock Ethel Mary 8 born 11 Jan 1907 in Workhouse 04 Jan 1915 Child of Annie Adcock Elizabeth Mattishall Sep 1845 29 Sep 1845 1841 16 Jan 1847 26 Jan 1847 Adcock John Jul 1871 May 1871 15 May 1871 10 Jul 1871 Adcock Ellen Jul 1882 3 Jul 1882 Adcock Edgar 17 Nov 1930 Adcock William died 7 Feb 1837 8476-639 Adcock Maria died 24 May 1838 8476-640 Addison George Great Dunham 16 May 1859 Alcock Alfred Aug 1870 son of Elizabeth 15 Aug 1870 Alcock Sarah Longham 6 Nov 1882 13 Jul 1885 Alcock Martha Beeston 20 Jan 1868 Alcock John 19 Oct 1896 Alderton Emily 14 Jul 1941 Aldous Edward Pensioner 09 Aug 1909 Aldous Elizabeth 89 Yaxham died 2 Jul 1908 DC Alkinson Elizabeth died 11 Nov 1837 8476-639 Allen Arthur Robert Matishall 08 Jun 1931 Allgood May daughter Mary Kettle -

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office This list summarises the Norfolk Record Office’s (NRO’s) holdings of parish (Church of England) registers and of transcripts and other copies of them. Parish Registers The NRO holds registers of baptisms, marriages, burials and banns of marriage for most parishes in the Diocese of Norwich (including Suffolk parishes in and near Lowestoft in the deanery of Lothingland) and part of the Diocese of Ely in south-west Norfolk (parishes in the deanery of Fincham and Feltwell). Some Norfolk parish records remain in the churches, especially more recent registers, which may be still in use. In the extreme west of the county, records for parishes in the deanery of Wisbech Lynn Marshland are deposited in the Wisbech and Fenland Museum, whilst Welney parish records are at the Cambridgeshire Record Office. The covering dates of registers in the following list do not conceal any gaps of more than ten years; for the populous urban parishes (such as Great Yarmouth) smaller gaps are indicated. Whenever microfiche or microfilm copies are available they must be used in place of the original registers, some of which are unfit for production. A few parish registers have been digitally photographed and the images are available on computers in the NRO's searchroom. The digital images were produced as a result of partnership projects with other groups and organizations, so we are not able to supply copies of whole registers (either as hard copies or on CD or in any other digital format), although in most cases we have permission to provide printout copies of individual entries. -

The House of Industry Gressenhall Norfolk

House of Industry 2014 The House of Industry Gressenhall Norfolk Fig. 1. Façade. Showing former well house and weather vane to the cupola. Inset - detail of doorway CONSERVATION PLAN 1 House of Industry 2014 4.1 Executive Plan An architecturally magnificent building of 1777 with a continuous written record of life in the workhouse from 1777 until 1948. 4.2 Preamble This report is written by Stephen Heywood MA, FSA, an architectural historian and Historic Buildings Officer for Norfolk County Council. The report relies on the hard work of Stephen Pope on the copious records of the workhouse held by the Norfolk Record Office (NRO) and on the lives of its guardians and inmates. His published booklet on the workhouse is full of original research and a valuable resource (Pope). Also consulted are the authoritative account by Kathryn Morrison entitled The Workhouse: A Study of Poor-Law Buildings in England (Morrison) and the Norfolk Historical Atlas (NHA 2005) with its two chapters on Norfolk Workhouses. This account concentrates on the buildings, which have not been looked at in detail before with architectural history as a prime concern. It is intended that the work will inform exhibition designers as well architects involved with repair and enhancement. Also it is hoped that the report will stimulate activities for visitors and volunteers centred on discovering the building. 4.3 Understanding the Heritage 4.3.1 Describe the Heritage 4.3.1.1 Introduction The House of Industry, as it was originally conceived, was built in order to accommodate the poor of the Hundreds of Mitford and Launditch. -

LOST VILLAGES of BRECKLAND This Cycle Ride Starts from the Village of Gressenhall, Where a Former 18Th C

16 CYCLING DISCOVERY MAP Starting point: Gressenhall (nr. Dereham), Norfolk Distance: 23 miles/37 km (or with short cut 19 miles/31 km) Type of route: Day ride - moderate, circular; on roads THE LOST VILLAGES OF BRECKLAND This cycle ride starts from the village of Gressenhall, where a former 18th C. workhouse depicts rural life through the ages. From here the route heads north through attractive countryside and villages to the untouched valley of the River Nar, representing old Norfolk at its best. In between lie the abandoned medieval hamlets of Little Bittering and Godwick, where the church ruins stand as a timely reminder. Along this route you can stroll amongst the earthworks of a lost village, explore a Saxon church’s round tower and discover a memorial to a champion boxer. Godwick Key to Symbols & Abbreviations Essential information B Cycle Parking Starting point: Gressenhall - village green; or Gressenhall Farm and Workhouse 3 Places of Interest (Museum of Norfolk Life) (located 3/4 mile east of village Z Refreshments towards B1146). ; Children Welcome 4 Alternative Litcham Common Local Nature Reserve. Located 1/4 mile south Picnic Site starting point: of B1145 at Litcham. Join the route by leaving the car park and P Shop turning L onto the road. Then at the T-j, turn L again, w Toilets SP ‘Tittleshall 2, Fakenham 8’. Pass through the village centre, y Tourist Information and then take the next L onto Front Street. At the T-j with the E Caution/Take care B1145, turn L (NS). Start from ‘direction no. 14’. -

NORFOLK RECORDS COMMITTEE Date: Friday, 08 November 2019

NORFOLK RECORDS COMMITTEE Date: Friday, 08 November 2019 Time: 10:30am Venue: Green Room, Archive Centre, County Hall, Norwich Persons attending the meeting are requested to turn off mobile phones. Membership Cllr Michael Chenery of Horsbrugh Substitute: Cllr Brian Iles Norfolk County Council (Chairman) Cllr Robert Kybird (Vice-Chairman) Breckland District Council Cllr Sally Button Norwich City Council Cllr Barry Duffin Substitute: Cllr Libby Glover South Norfolk District Council Cllr Phillip Duigan Substitute: Cllr Brian Iles Norfolk County Council Cllr Virginia Gay North Norfolk District Council King's Lynn & West Norfolk Cllr Elizabeth Nockolds Borough Council Cllr Grant Nurden Substitute: Cllr David King Broadland District Council Cllr David Rowntree Substitute: Cllr Mike Sands Norfolk County Council Cllr Nigel Utton Norwich City Council Cllr Trevor Wainwright Great Yarmouth Borough Council Cllr Alan Waters Norwich City Council Non-Voting Members Mr Michael Begley Co-opted Member The Lady Dannatt MBE Custos Rotulorum Dr G. Alan Metters Representative of the Norfolk Record Society Dr Victor Morgan Observer Prof. Carole Rawcliffe Co-Opted Member Revd. Charles Read Representative of the Bishop of Norwich Mr Alan Steynor Co-opted Member For further details and general enquiries about this Agenda please contact the Committee Officer: Hollie Adams on 01603 223 029 or email [email protected] Under the Council’s protocol on the use of media equipment at meetings held in public, this meeting may be filmed, recorded or photographed. Anyone who wishes to do so must inform the Chairman and ensure that it is done in a manner clearly visible to anyone present. The wishes of any individual not to be recorded or filmed must be appropriately respected. -

NORFOLK. SMI 793 Dyball Alfred, West Raynham, Faken- Hales William Geo

TRADES DIRECTORY. J NORFOLK. SMI 793 Dyball Alfred, West Raynham, Faken- Hales William Geo. Ingham, Norwich Kitteringham John, Tilney St. Law- ham Hall P. Itteringham, Aylsham R.S.O rence, Lynn Dyball E. T. 24 Fuller's hill, Yarmouth Hammond F. Barroway Drove, Downhm Knights Edwd. H. London rd. Harleston Dye Henry Samuel, 39 Audley street & Hammond Richard, West Bilney, Lynn Knott Charles, Ten Mile Bank, Downhm North Market road, Yarmouth & at Pentney, Swaffham Kybird J ames, Croxton, Thetford Earl Uriah, Coltishall, Norwich Hammond Robert Edward Hazel, Lade Frederick Wacton, Long Stratton Easter Frederick, Mileham, Swaffham Gayton, Lynn Lake Thomas, Binham, Wighton R.S.O Easter George, Blofield, Norwich Hammond William, Stow Bridge, Stow Lambert William Claydon, Wiggenhall Ebbs William, Alburgh, Harleston Bardolph, Downham St. Mary Magdalen, Lynn Edward Alfred, Griston, Thetford Hanton J ames, W estEnd street, Norwich Langham Alfred, Martham, Yarmouth Edwards Edward, Wretham, Great Harbord P. Burgh St. Margaret, Yarmth Lansdell Brothers, Hempnall, Norwich Hockham, Thetford Hardy Harry, Lake's end, Wisbech Lansdell Albert, Stratton St. Mary, Eggleton W. Great Ryburgh, Fakenham Harper Robt. Alfd. Halvergate, Nrwch Long Stratton R.S.O Eglington & Gooch, Hackford, Norwich Harrold Samuel, Church end, West Larner Henry, Stoke Ferry ~.0 Eke Everett, Mulbarton, Norwich Walton, Wisbech Last F. B. 93 Sth. Market rd. Yarmouth Eke Everet, Bracon Ash, Norwich Harrowven Henry, Catton, Norwich Lawes Harry Wm. Cawshm, Norwich Eke James, Saham Ton.ey, Thetford Hawes A. Terrington St. John, Wisbech Laws .Jo~eph, Spixworth, Norwich Eke R. Drayton, Norwich Hawes Robert Hilton, Terrington St. Leader James, Po!'ltwick, Norwich Ellis Charles, Palling, Norwich Clement, Lynn Leak T. -

Norfolk Map Books

Scoulton Wicklewood Hingham Wymondham Division Arrangements for Deopham Little Ellingham Attleborough Morley Hingham County District Final Recommendations Spooners Row Yare & Necton Parish Great Ellingham Besthorpe Rocklands Attleborough Attleborough Bunwell Shropham The Brecks West Depwade Carleton Rode Old Buckenham Snetterton Guiltcross Quidenham 00.375 0.75 1.5 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016 © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OSGD New Buckenham 100049926 2016 Tibenham Bylaugh Beetley Mileham Division Arrangements for Dereham North & Scarning Swanton Morley Hoe Elsing County District Longham Beeston with Bittering Launditch Final Recommendations Parish Gressenhall North Tuddenham Wendling Dereham Fransham Dereham North & Scarning Dereham South Scarning Mattishall Elmham & Mattishall Necton Yaxham Whinburgh & Westfield Bradenham Yare & Necton Shipdham Garvestone 00.425 0.85 1.7 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016 © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OSGD Holme Hale 100049926 2016 Cranworth Gressenhall Dereham North & Scarning Launditch Division Arrangements for Dereham South County District Final Recommendations Parish Dereham Scarning Dereham South Yaxham Elmham & Mattishall Shipdham Whinburgh & Westfield 00.125 0.25 0.5 Yare & Necton Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016 © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OSGD 100049926 2016 Sculthorpe Fakenham Erpingham Kettlestone Fulmodeston Hindolveston Thurning Erpingham -

I T Tl Rrotluil 0R Ilo[F0lr Un

(} J t I ri 6R["TJL'HALL r . .l rAi Ft AttD h'0RrH00t[ I t tl rrotluil 0r ilo[f0lr un Gressenhall Farm & Workhouse, part of Norfolk Museums Service. Update for Gressenhall Parish Council May 2019 1. EvEnts & Activities This past year we have been busy delivering our broad programme of events, ranging from Days with a Difference - small scale themed events where additional activities are on offer alongside our permanent offer, to Special Event days - major events which attract a wider audience and significant additional activities on offer. We have also opened for specially programmed, pre-bookable & ticketed events outside our normal opening season - speciflcally Victorian Famity Christmason 20'n & 21't December 2018 and opening between 18'n & 22d February 2019 to coincide with the schools half term. The events programme, as always, has proven very popular attracting large audiences with our Vitlage at War 2018 event attracting circa 3000 visitors across the two-days. Special Event days for 2019 include: ' Retro Revivalon Monday 27'n May ' Viltage at Waron Sunday 25" & Monday 26th August t Appte Day on Sunday 13tn October Gressenhall Farm and Workhouse will also be participating in national programmes offering free admission in 2019: Open Farm Sunday in June, working with the County Farms team, and Heritage Open Day in September. Our 2019 event programme is already undenuay, with full details available on the museum website www. m u seu ms. norfolk. gov. u k/G resse n ha I I 2. Projects & Developments Following the successful grant award af f.1.47m (79o/o') from the Heritage Lottery Fund for the Voices from the Workhouse project, the redeveloped workhouse spaces were formally launched in July 2016 with the new final displays within the first floor Collections Gallery being formally launched on 10 March 2A18. -

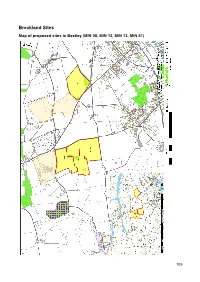

Breckland Sites Map of Proposed Sites in Beetley (MIN 08, MIN 12, MIN 13, MIN 51)

Breckland Sites Map of proposed sites in Beetley (MIN 08, MIN 12, MIN 13, MIN 51) 105 MIN 12 - land north of Chapel Lane, Beetley Site Characteristics • The 16.38 hectare site is within the parish of Beetley • The estimated sand and gravel resource at the site is 1,175,000 tonnes • The proposer of the site has given a potential start date of 2025 and estimated the extraction rate to be 80,000 tonnes per annum. Based on this information the full mineral resource at the site could be extracted within 15 years, therefore approximately 960,000 tonnes could be extracted within the plan period. • The site is proposed by Middleton Aggregates Ltd as an extension to an existing site. • The site is currently in agricultural use and the Agricultural Land Classification scheme classifies the land as being Grade 3. • The site is 3.7km from Dereham and 12km from Fakenham, which are the nearest towns. A reduced extraction area has been proposed of 14.9 hectares, which creates standoff areas to the south west of the site nearest to the buildings on Chapel Lane, and to the north west of the site nearest the dwellings on Church Lane. M12.1 Amenity: The nearest residential property is 11m from the site boundary. There are 22 sensitive receptors within 250m of the site boundary and six of these are within 100m of the site boundary. The settlement of Beetley is 260m away and Old Beetley is 380m away. However, land at the north-west and south-west corners is not proposed to be extracted.