Der Gerettete Alberich (Alberich Saved), Fantasy for Solo Percussion and Orchestra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

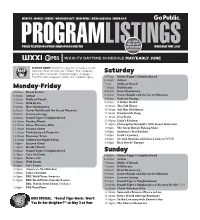

WXXI Program Guide | May 2021

WXXI-TV | WORLD | CREATE | WXXI KIDS 24/7 | WXXI NEWS | WXXI CLASSICAL | WRUR 88.5 SEE CENTER PAGES OF CITY PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER LISTINGSFOR WXXI SHOW MAY/EARLY JUNE 2021 HIGHLIGHTS! WXXI-TV DAYTIME SCHEDULE MAY/EARLY JUNE PLEASE NOTE: WXXI-TV’s daytime schedule listed here runs from 6:00am to 7:00pm. The complete prime time television schedule begins on page 2. Saturday The PBS Kids programs below are shaded in gray. 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 6:30am Arthur 7vam Molly of Denali Monday-Friday 7:30am Wild Kratts 6:00am Ready Jet Go! 8:00am Hero Elementary 6:30am Arthur 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 7:00am Molly of Denali 9:00am Curious George 7:30am Wild Kratts 9:30am A Wider World 8:00am Hero Elementary 10:00am This Old House 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 10:30am Ask This Old House 9:00am Curious George 11:00am Woodsmith Shop 9:30am Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood 11:30am Ciao Italia 10:00am Donkey Hodie 12:00pm Lidia’s Kitchen 10:30am Elinor Wonders Why 12:30pm Christopher Kimball’s Milk Street Television 11:00am Sesame Street 1:00pm The Great British Baking Show 11:30am Pinkalicious & Peterrific 2:00pm America’s Test Kitchen 12:00pm Dinosaur Train 2:30pm Cook’s Country 12:30pm Clifford the Big Red Dog 3:00pm Second Opinion with Joan Lunden (WXXI) 1:00pm Sesame Street 3:30pm Rick Steves’ Europe 1:30pm Donkey Hodie 2:00pm Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Sunday 2:30pm Let’s Go Luna! 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 3:00pm Nature Cat 6:30am Arthur 3:30pm Wild Kratts 7:00am Molly -

Juilliard Orchestra Marin Alsop, Conductor Daniel Ficarri, Organ Daniel Hass, Cello

Saturday Evening, January 25, 2020, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents Juilliard Orchestra Marin Alsop, Conductor Daniel Ficarri, Organ Daniel Hass, Cello SAMUEL BARBER (1910–81) Toccata Festiva (1960) DANIEL FICARRI, Organ DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–75) Cello Concerto No. 2 in G major, Op. 126 (1966) Largo Allegretto Allegretto DANIEL HASS, Cello Intermission CHRISTOPHER ROUSE (1949–2019) Processional (2014) JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833–97) Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73 (1877) Allegro non troppo Adagio non troppo Allegretto grazioso Allegro con spirito Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 50 minutes, including an intermission This performance is made possible with support from the Celia Ascher Fund for Juilliard. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. Juilliard About the Program the organ’s and the orchestra’s full ranges. A fluid approach to rhythm and meter By Jay Goodwin provides momentum and bite, and intricate passagework—including a dazzling cadenza Toccata Festiva for the pedals that sets the organist’s feet SAMUEL BARBER to dancing—calls to mind the great organ Born: March 9, 1910, in West Chester, music of the Baroque era. Pennsylvania Died: January 23, 1981, in New York City Cello Concerto No. 2 in G major, Op. 126 DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH In terms of scale, pipe organs are Born: September 25, 1906, in Saint Petersburg different from every other type of Died: August 9, 1975, in Moscow musical instrument, and designing and assembling a new one can be a challenge There are several reasons that of architecture and engineering as complex Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. -

Themenkatalog »Musik Verfolgter Und Exilierter Komponisten«

THEMENKATALOG »Musik verfolgter und exilierter Komponisten« 1. Alphabetisches Verzeichnis Babin, Victor Capriccio (1949) 12’30 3.3.3.3–4.3.3.1–timp–harp–strings 1908–1972 for orchestra Concerto No.2 (1956) 24’ 2(II=picc).2.2.2(II=dbn)–4.2.3.1–timp.perc(3)–strings for two pianos and orchestra Blech, Leo Das war ich 50’ 2S,A,T,Bar; 2(II=picc).2.corA.2.2–4.2.0.1–timp.perc–harp–strings 1871–1958 (That Was Me) (1902) Rural idyll in one act Libretto by Richard Batka after Johann Hutt (G) Strauß, Johann – Liebeswalzer 3’ 2(picc).1.2(bcl).1–3.2.0.0–timp.perc–harp–strings Blech, Leo / for coloratura soprano and orchestra Sandberg, Herbert Bloch, Ernest Concerto Symphonique (1947–48) 38’ 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn–4.3.3.1–timp.perc(3):cyms/tam-t/BD/SD 1880–1959 for piano and orchestra –cel–strings String Quartet No.2 (1945) 35’ Suite Symphonique (1944) 20’ 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn–4.3.3.1–timp.perc:cyms/BD–strings Violin Concerto (1937–38) 35’ 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn–4.3.3.1–timp.perc(2):cyms/tgl/BD/SD– harp–cel–strings Braunfels, Walter 3 Chinesische Gesänge op.19 (1914) 16’ 3(III=picc).2(II=corA).3.2–4.2.3.1–timp.perc–harp–cel–strings; 1882–1954 for high voice and orchestra reduced orchestraion by Axel Langmann: 1(=picc).1(=corA).1.1– Text: from Hans Bethge’s »Chinese Flute« (G) 2.1.1.0–timp.perc(1)–cel(=harmonium)–strings(2.2.2.2.1) 3 Goethe-Lieder op.29 (1916/17) 10’ for voice and piano Text: (G) 2 Lieder nach Hans Carossa op.44 (1932) 4’ for voice and piano Text: (G) Cello Concerto op.49 (c1933) 25’ 2.2(II=corA).2.2–4.2.0.0–timp–strings -

Assenet Inlays Cycle Ring Wagner OE

OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 1 An Introduction to... OPERAEXPLAINED WAGNER The Ring of the Nibelung Written and read by Stephen Johnson 2 CDs 8.558184–85 OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 2 An Introduction to... WAGNER The Ring of the Nibelung Written and read by Stephen Johnson CD 1 1 Introduction 1:11 2 The Stuff of Legends 6:29 3 Dark Power? 4:38 4 Revolution in Music 2:57 5 A New Kind of Song 6:45 6 The Role of the Orchestra 7:11 7 The Leitmotif 5:12 Das Rheingold 8 Prelude 4:29 9 Scene 1 4:43 10 Scene 2 6:20 11 Scene 3 4:09 12 Scene 4 8:42 2 OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 3 Die Walküre 13 Background 0:58 14 Act I 10:54 15 Act II 4:48 TT 79:34 CD 2 1 Act II cont. 3:37 2 Act III 3:53 3 The Final Scene: Wotan and Brünnhilde 6:51 Siegfried 4 Act I 9:05 5 Act II 7:25 6 Act III 12:16 Götterdämmerung 7 Background 2:05 8 Prologue 8:04 9 Act I 5:39 10 Act II 4:58 11 Act III 4:27 12 The Final Scene: The End of Everything? 11:09 TT 79:35 3 OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 4 Music taken from: Das Rheingold – 8.660170–71 Wotan ...............................................................Wolfgang Probst Froh...............................................................Bernhard Schneider Donner ....................................................................Motti Kastón Loge........................................................................Robert Künzli Fricka...............................................................Michaela -

Sound out Loud Ensemble New Arts Venture Challenge Grant Proposal

Sound Out Loud Ensemble New Arts Venture Challenge Grant Proposal April 5, 2016 Satoko Hayami DMA Candidate in Collaborative Piano, School of Music Executive Summary History and Makeup of Sound Out Loud Sound Out Loud (SOL) is a new music ensemble that recently launched in Madison. SOL is comprised of 7 forwardlooking, classically trained musicians, which includes 2 pianists, 1 percussionist, 1 flutist, 1 clarinetist, 1 violinist and 1 cellist. The group is lead by pianists Satoko Hayami and Kyle Johnson, a percussionist Garrett Mendelow. Mission SOL’s mission is to create a growing circle of musicians and audiences to share the excitement of the innovative, contemporary language of newly/recently composed classical music through a series of creative concerts and presentations primarily in the city of Madison. SOL also commissions works of young upcoming composers to enrich the repertoire of the genre. SOL believes that progressive new classical music expands the audience’s existing perspectives of music, and therefore further enhances their appreciation toward music in general. SOL also understands that new music’s relatable contemporary language helps the audience reconnect with conventional classical music, as inherited by contemporary classical music. Through commitment to contemporary classical music, SOL’s hope is to cultivate a sense of freedom toward classical music as well as toward other aspects of life, without the limitation of a conventional concept of music. Method SOL thrives to present highenergy performances of dynamic programs which are intellectually and emotionally inspirational for a wide array of audiences (including both classical music lovers and non classical music lovers). -

College Orchestra Director Programming Decisions Regarding Classical Twentieth-Century Music Mark D

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Dissertations The Graduate School Summer 2017 College orchestra director programming decisions regarding classical twentieth-century music Mark D. Taylor James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019 Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, Mark D., "College orchestra director programming decisions regarding classical twentieth-century music" (2017). Dissertations. 132. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019/132 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. College Orchestra Director Programming Decisions Regarding Classical Twentieth-Century Music Mark David Taylor A Doctor of Musical Arts Document submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music August 2017 FACULTY COMMITTEE Committee Chair: Dr. Eric Guinivan Committee Members/ Readers: Dr. Mary Jean Speare Mr. Foster Beyers Acknowledgments Dr. Robert McCashin, former Director of Orchestras and Professor of Orchestral Conducting at James Madison University (JMU) as well as a co-founder of College Orchestra Directors Association (CODA), served as an important sounding-board as the study emerged. Dr. McCashin was particularly helpful in pointing out the challenges of undertaking such a study. I would have been delighted to have Dr. McCashin serve as the chair of my doctoral committee, but he retired from JMU before my study was completed. -

Richard Danielpour

Rental orders, fee quotations, and manuscript editions: G. Schirmer/AMP Rental and Performance Department P.O. Box 572 Chester, NY 10918 RICHARD (845) 469-4699 — phone (845) 469-7544 — fax [email protected] DANIELPOUR For music in print, contact your local dealer. Hal Leonard Corporation is the exclusive print distributor for G. Schirmer, Inc. and Associated Music Publishers, Inc. PO Box 13819 Milwaukee, WI 53213 www.halleonard.com — web Perusal materials (when available): G. Schirmer/AMP Promotion Dept. 257 Park Avenue South 20th Floor New York, NY 10010 (212) 254-2100 — phone (212) 254-2013 — fax [email protected] Publisher and Agency Representation for the Music Sales Group of Companies: www.schirmer.com CHESTER MUSIC LTD NOVELLO & CO LTD 8/9 Frith Street London W1D 3JB, England CHESTER MUSIC FRANCE PREMIERE MUSIC GROUP SARL 10, rue de la Grange-Batelire 75009 Paris, France CHESTER SCHIRMER BERLIN Dorotheenstr. 3 D-10117 Berlin, Germany EDITION WILHELM HANSEN AS Bornholmsgade 1 DK-1266 Copenhagen K, Denmark KK MUSIC SALES c/o Shinko Music Publishing Co Ltd 2-1 Ogawa-machi, Kanda Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 101, Japan G. SCHIRMER, INC. ASSOCIATED MUSIC PUBLISHERS, INC. 257 Park Avenue South, 20th Floor New York, NY 10010, USA G. SCHIRMER PTY LTD 4th Floor, Lisgar House 32 Carrington St. Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia SHAWNEE PRESS 1221 17th Ave. South Nashville, TN 37212, USA UNIÓN MUSICAL EDICIONES SL C/ Marqués de la Ensenada 4, 3o. 28004 Madrid, Spain Photo: Mike Minehan RICHARD DANIELPOUR Richard Danielpour has established himself as one of the most gifted and sought-after composers of his generation. -

Prospero's Rooms

2020 FEB HADELICH PLAYS PAGANINI 2019-20 HAL & JEANETTE SEGERSTROM FAMILY FOUNDATION CLASSICAL SERIES Michael Francis, conductor Rouse PROSPERO’S ROOMS Augustin Hadelich, violin Paganini VIOLIN CONCERTO NO. 1 IN D MAJOR Allegro maestoso Adagio Rondo: Allegro spiritoso Augustin Hadelich Intermission Rachmaninoff SYMPHONY NO. 3 IN A MINOR Lento—Allegro moderato—Allegro Adagio ma non troppo—Allegro Allegro—Allegro vivace Thursday, February 27, 2020 @ 8 p.m. Friday, February 28, 2020 @ 8 p.m. The appearances of Augustin Hadelich and Saturday, February 29, 2020 @ 8 p.m. Michael Francis have been generously underwritten by Segerstrom Center for the Arts a gift from Sam and Lyndie Ersan. Renée and Henry Segerstrom Concert Hall OFFICIAL MEDIA SPONSOR This concert is being recorded for broadcast on Sunday, March 15, 2020, on Classical KUSC. PacificSymphony.org FEB 2020 5 PROGRAM NOTES in the world of atonality; yet he was also a influenced his compositional as well as rock’n’roll fan (Led Zeppelin was a favorite) his playing style. and taught a class on the history of rock None of this even begins to suggest Christopher Rouse: while on the faculty at the Eastman School the nature or extent of Paganini’s of Music. celebrity, which spread through Italy Prospero’s Rooms Regarding Prospero’s Rooms, Rouse and then took Europe by storm. After an Lovers of classical noted on his website: “In the days when I 1813 concert at Milan’s La Scala opera music lost one would have still contemplated composing house, he was spoken of in the same of their own in an opera, my preferred source was Edgar reverential tones as other great violinists, 2019 when the Allan Poe’s ‘Masque of the Red Death.’… including Charles Philippe Lafont and Pulitzer Prize- However… I decided to redirect my ideas Louis Spohr. -

Die Münchner Philharmoniker

Die Münchner Philharmoniker Die Münchner Philharmoniker wurden 1893 auf Privatinitiative von Franz Kaim, Sohn eines Klavierfabrikanten, gegründet und prägen seither das musikalische Leben Münchens. Bereits in den Anfangsjahren des Orchesters – zunächst unter dem Namen »Kaim-Orchester« – garantierten Dirigenten wie Hans Winderstein, Hermann Zumpe und der Bruckner-Schüler Ferdinand Löwe hohes spieltechnisches Niveau und setzten sich intensiv auch für das zeitgenössische Schaffen ein. Von Anbeginn an gehörte zum künstlerischen Konzept auch das Bestreben, durch Programm- und Preisgestaltung allen Bevölkerungs-schichten Zugang zu den Konzerten zu ermöglichen. Mit Felix Weingartner, der das Orchester von 1898 bis 1905 leitete, mehrte sich durch zahlreiche Auslandsreisen auch das internationale Ansehen. Gustav Mahler dirigierte das Orchester in den Jahren 1901 und 1910 bei den Uraufführungen seiner 4. und 8. Symphonie. Im November 1911 gelangte mit dem inzwischen in »Konzertvereins-Orchester« umbenannten Ensemble unter Bruno Walters Leitung Mahlers »Das Lied von der Erde« zur Uraufführung. Von 1908 bis 1914 übernahm Ferdinand Löwe das Orchester erneut. In Anknüpfung an das triumphale Wiener Gastspiel am 1. März 1898 mit Anton Bruckners 5. Symphonie leitete er die ersten großen Bruckner- Konzerte und begründete so die bis heute andauernde Bruckner-Tradition des Orchesters. In die Amtszeit von Siegmund von Hausegger, der dem Orchester von 1920 bis 1938 als Generalmusikdirektor vorstand, fielen u.a. die Uraufführungen zweier Symphonien Bruckners in ihren Originalfassungen sowie die Umbenennung in »Münchner Philharmoniker«. Von 1938 bis zum Sommer 1944 stand der österreichische Dirigent Oswald Kabasta an der Spitze des Orchesters. Eugen Jochum dirigierte das erste Konzert nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg. Mit Hans Rosbaud gewannen die Philharmoniker im Herbst 1945 einen herausragenden Orchesterleiter, der sich zudem leidenschaftlich für neue Musik einsetzte. -

WAGNER and the VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’S Works Is More Closely Linked with Old Norse, and More Especially Old Icelandic, Culture

WAGNER AND THE VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’s works is more closely linked with Old Norse, and more especially Old Icelandic, culture. It would be carrying coals to Newcastle if I tried to go further into the significance of the incom- parable eddic poems. I will just mention that on my first visit to Iceland I was allowed to gaze on the actual manuscript, even to leaf through it . It is worth noting that Richard Wagner possessed in his library the same Icelandic–German dictionary that is still used today. His copy bears clear signs of use. This also bears witness to his search for the meaning and essence of the genuinely mythical, its very foundation. Wolfgang Wagner Introduction to the program of the production of the Ring in Reykjavik, 1994 Selma Gu›mundsdóttir, president of Richard-Wagner-Félagi› á Íslandi, pre- senting Wolfgang Wagner with a facsimile edition of the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda on his eightieth birthday in Bayreuth, August 1999. Árni Björnsson Wagner and the Volsungs Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen Viking Society for Northern Research University College London 2003 © Árni Björnsson ISBN 978 0 903521 55 0 The cover illustration is of the eruption of Krafla, January 1981 (Photograph: Ómar Ragnarsson), and Wagner in 1871 (after an oil painting by Franz von Lenbach; cf. p. 51). Cover design by Augl‡singastofa Skaparans, Reykjavík. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 7 BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD WAGNER ............................ 17 CHRONOLOGY ............................................................................... 64 DEVELOPMENT OF GERMAN NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS ..68 ICELANDIC STUDIES IN GERMANY ......................................... -

“Voices of the People”

The UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music Department of Music Presents UCLA Symphonic Band Travis J. Cross Conductor Ian Richard Graduate Assistant Conductor UCLA Wind Ensemble Travis J. Cross Conductor “Voices of the People” Wednesday, May 27, 2015 8:00 p.m. Schoenberg Hall — PROGRAM — The Foundation ........................................................... Richard Franko Goldman Symphony No. 4 for Winds and Percussion ......................... Andrew Boysen, Jr. Fast Smooth and Flowing Scherzo and Trio Fast Salvation Is Created ................................................................. Pavel Chesnokov arranged by Bruce Houseknecht Fortress ........................................................................................... Frank Ticheli Undertow ........................................................................................ John Mackey — INTERMISSION — Momentum .................................................................................... Stephen Spies world premiere performance Vox Populi ........................................................................... Richard Danielpour transcribed by Jack Stamp Carmina Burana .................................................................................... Carl Orff transcribed by John Krance O Fortuna, velut Luna Fortune plango vulnera Ecce gratum Tanz—Uf dem anger Floret silva Were diu werlt alle min Amor volat undique Ego sum abbas In taberna quando sumus In trutina Dulcissime Ave formosissima Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi * * * Please join the members of the -

For Release: Tk, 2013

FOR RELEASE: January 23, 2013 SUPPLEMENT CHRISTOPHER ROUSE, The Marie-Josée Kravis COMPOSER-IN-RESIDENCE WORLD PREMIERE of SYMPHONY NO. 4 at the NY PHIL BIENNIAL New York Premiere of REQUIEM To Open Spring For Music Festival at Carnegie Hall New York Premiere of OBOE CONCERTO with Principal Oboe Liang Wang RAPTURE at Home and on ASIA / WINTER 2014 Tour Rouse To Advise on CONTACT!, the New-Music Series, Including New Partnership with 92nd Street Y ____________________________________ “What I’ve always loved most about the Philharmonic is that they play as though it’s a matter of life or death. The energy, excitement, commitment, and intensity are so exciting and wonderful for a composer. Some of the very best performances I’ve ever had have been by the Philharmonic.” — Christopher Rouse _______________________________________ American composer Christopher Rouse will return in the 2013–14 season to continue his two- year tenure as the Philharmonic’s Marie-Josée Kravis Composer-in-Residence. The second person to hold the Composer-in-Residence title since Alan Gilbert’s inaugural season, following Magnus Lindberg, Mr. Rouse’s compositions and musical insights will be highlighted on subscription programs; in the Philharmonic’s appearance at the Spring For Music festival; in the NY PHIL BIENNIAL; on CONTACT! events; and in the ASIA / WINTER 2014 tour. Mr. Rouse said: “Part of the experience of music should be an exposure to the pulsation of life as we know it, rather than as people in the 18th or 19th century might have known it. It is wonderful that Alan is so supportive of contemporary music and so involved in performing and programming it.” 2 Alan Gilbert said: “I’ve always said and long felt that Chris Rouse is one of the really important composers working today.