Richard Danielpour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Voices of the People”

The UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music Department of Music Presents UCLA Symphonic Band Travis J. Cross Conductor Ian Richard Graduate Assistant Conductor UCLA Wind Ensemble Travis J. Cross Conductor “Voices of the People” Wednesday, May 27, 2015 8:00 p.m. Schoenberg Hall — PROGRAM — The Foundation ........................................................... Richard Franko Goldman Symphony No. 4 for Winds and Percussion ......................... Andrew Boysen, Jr. Fast Smooth and Flowing Scherzo and Trio Fast Salvation Is Created ................................................................. Pavel Chesnokov arranged by Bruce Houseknecht Fortress ........................................................................................... Frank Ticheli Undertow ........................................................................................ John Mackey — INTERMISSION — Momentum .................................................................................... Stephen Spies world premiere performance Vox Populi ........................................................................... Richard Danielpour transcribed by Jack Stamp Carmina Burana .................................................................................... Carl Orff transcribed by John Krance O Fortuna, velut Luna Fortune plango vulnera Ecce gratum Tanz—Uf dem anger Floret silva Were diu werlt alle min Amor volat undique Ego sum abbas In taberna quando sumus In trutina Dulcissime Ave formosissima Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi * * * Please join the members of the -

LIVE from COLUMBIA Pop-Ups from Morningside Campus

VIEW THIS EMAIL IN YOUR BROWSER FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PRESS CONTACTS August 17, 2021 Aleba Gartner, 212/206-1450 millertheatre.com [email protected] Lauren Bailey Cognetti, [email protected] "Those thirty minutes number among the most intense I’ve experienced as a listener... The close-up, multiple angle and high resolution shots of the performance gave a view not even accessible to an audience member sitting in the front row.” — Elizabeth Lyon in The Hudson Review Miller Theatre at Columbia University School of the Arts announces LIVE FROM COLUMBIA Pop-Ups from Morningside Campus Co-presented with Columbia School of the Arts Miller Theatre continues its popular Pop-Up Concerts series, offering audiences a virtual front-row seat to three performances filmed on Columbia University's Morningside campus. Virtual • Free as always Featuring performances by Arturo O'Farrill & the Afro Latin Jazz Orchestra Filmed from the Miller Theatre stage Live Stream: Saturday, September 18 at 4pm Simone Dinnerstein, piano Filmed in Butler Library's famous reading room Video Premiere: Tuesday, October 12 at 7pm Yarn/Wire Filmed from the Miller Theatre stage Video Premiere: Tuesday. November 9 at 7pm Concerts in the Live from Columbia series are livestreamed or filmed live and premiered throughout the Fall 2021 season, with on-demand streaming available immediately after. millertheatre.com/live-from-columbia * Miller Theatre will announce its full 2021-22 season later this fall. From Melissa Smey, Executive Director Arts Initiative and Miller Theatre: "I am thrilled to continue our Live from Columbia series with the School of the Arts, welcoming a global audience to incredible, free performances. -

A Global Sampling of Piano Music from 1978 to 2005: a Recording Project

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: A GLOBAL SAMPLING OF PIANO MUSIC FROM 1978 TO 2005 Annalee Whitehead, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2011 Dissertation directed by: Professor Bradford Gowen Piano Division, School of Music Pianists of the twenty-first century have a wealth of repertoire at their fingertips. They busily study music from the different periods Baroque, Classical, Romantic, and some of the twentieth century trying to understand the culture and performance practice of the time and the stylistic traits of each composer so they can communicate their music effectively. Unfortunately, this leaves little time to notice the composers who are writing music today. Whether this neglect proceeds from lack of time or lack of curiosity, I feel we should be connected to music that was written in our own lifetime, when we already understand the culture and have knowledge of the different styles that preceded us. Therefore, in an attempt to promote today’s composers, I have selected piano music written during my lifetime, to show that contemporary music is effective and worthwhile and deserves as much attention as the music that preceded it. This dissertation showcases piano music composed from 1978 to 2005. A point of departure in selecting the pieces for this recording project is to represent the major genres in the piano repertoire in order to show a variety of styles, moods, lengths, and difficulties. Therefore, from these recordings, there is enough variety to successfully program a complete contemporary recital from the selected works, and there is enough variety to meet the demands of pianists with different skill levels and recital programming needs. -

A Performer's Guide to Richard Danielpour's a Woman's Life Carline Waugh Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2015 A Performer's Guide to Richard Danielpour's A Woman's Life Carline Waugh Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Waugh, Carline, "A Performer's Guide to Richard Danielpour's A Woman's Life" (2015). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2542. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2542 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO RICHARD DANIELPOUR’S A WOMAN’S LIFE A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Carline Waugh B.M Performance, Atlantic Union College, 2009 M.M, Performance, University of Mississippi, 2012 August 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Mr. Richard Danielpour for creating this wonderful work and for giving of his time throughout this project. I also would like to thank Ms. Angela Brown for her tremendous wisdom and insight. I would like to extend sincere thanks to the chair of my committee and major professor, Dr. Loraine Sims for her continuous guidance and kindness. You truly are an inspiration to me. -

Press Kit About the Nashville Symphony

Nashville Symphony 2019/2020 Press Kit About the Nashville Symphony ed by music director Giancarlo Guerrero, the Nashville Symphony has been professional orchestra careers. Currently, 20 participating students receive individual Lan integral part of the Music City sound since 1946. The 83-member ensemble instrument instruction, performance opportunities, and guidance on applying to performs more than 150 concerts annually, with a focus on contemporary American colleges and conservatories, all offered free of charge. orchestral music through collaborations with composers including Jennifer Higdon, Terry Riley, Joan Tower and Aaron Jay Kernis. The orchestra is equally renowned for Schermerhorn Symphony Center, the orchestra’s home since 2006, is considered one of its commissioning and recording projects with Nashville-based artists including bassist the world’s finest acoustical venues. Named in honor of former music director Kenneth Edgar Meyer, banjoist Béla Fleck, singer-songwriter Ben Folds and electric bassist Victor Schermerhorn and located in the heart of downtown Nashville, the building boasts Wooten. distinctive neo-Classical architecture incorporating motifs and design elements that pay homage to the history, culture and people of Middle Tennessee. Within its intimate An established leader in Nashville’s arts and cultural community, the Symphony has design, the 1,800-seat Laura Turner Hall contains several unique features, including facilitated several community collaborations and initiatives, most notably Violins soundproof windows, the 3,500-pipe Martin Foundation Concert Organ, and an of Hope Nashville, which spotlighted a historic collection of instruments played by innovative mechanical system that transforms the hall from theater-style seating to a Jewish musicians during the Holocaust. -

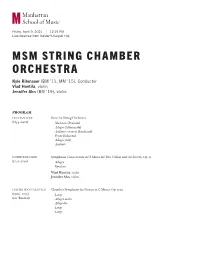

Msm String Chamber Orchestra

Friday, April 9, 2021 | 12:15 PM Livestreamed from Neidorff-Karpati Hall MSM STRING CHAMBER ORCHESTRA Kyle Ritenauer (BM ’11, MM ’15), Conductor Vlad Hontila, violin Jennifer Ahn (BM ’19), violin PROGRAM LEOS JANÁČEK Suite for String Orchestra (1854–1928) Moderato (Prelude) Adagio (Allemande) Andante con moto (Saraband) Presto (Scherzo) Adagio (Air) Andante JOSEPH BOLOGNE Symphonie Concertante in G Major for Two Violins and Orchestra, Op. 13 (1745–1799) Allegro Rondeau Vlad Hontila, violin Jennifer Ahn, violin DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Chamber Symphony for Strings in C Minor, Op. 110a (1906–1975) Largo (arr. Barshai) Allegro molto Allegretto Largo Largo MSM STRING CHAMBER ORCHESTRA VIOLIN 1 VIOLIN 2 VIOLA DOUBLE BASS HORN Corinne Au Selin Algoz Leah Glick Dylan Holly Emma Potter Short Hills, New Jersey Istanbul, Turkey Jerusalem, Israel Tucson, Arizona Surprise, Arizona Ally Cho Luxi Wang Dudley Raine Sophia Filippone Melbourne, Australia Sichuan, China Lynchburg, Virginia OBOE Glen Mills, Pennsylvania Messiah Ahmed Carolyn Carr Ellen O’Neill Dallas, Texas Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania CELLO New York, New York Edward Luengo Andres Ayola Miami, Florida New York, New York Pedro Bonet Madrid, Spain Students in this performance are supported by the L. John Twiford Music Scholarship, and the Herbert R. and Evelyn Axelrod Scholarship. We are grateful to the generous donors who made these scholarships possible. For information on establishing a named scholarship at Manhattan School of Music, please contact Susan Madden, Vice President for Advancement, at 917-493-4115 or [email protected]. ABOUT THE ARTISTS Kyle Ritenauer, Conductor Acclaimed New York-based conductor Kyle Ritenauer is establishing himself as one of classical and contemporary music’s singular artistic leaders. -

Music Director/Conductor

Inspired Tradition Program Notes Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 1, in G Major, Op. 78 Johannes Brahms Born May 7, 1833, in Hamburg Died April 3, 1897, in Vienna In his first twenty years, Johannes Brahms made an astonishing leap, from a miserable childhood in the downtrodden harbor area of Hamburg to an eminent position as a distinguished young composer. He began his career as a musician at the age of twelve by giving piano lessons for pennies, and at thirteen, he was playing in the harbor-side sailors’ bars. By the age of sixteen, however, he had progressed to playing Beethoven’s Waldstein Sonata as well as one of his own compositions in a public concert. In April 1853, just before his twentieth birthday, he set out from Hamburg on a modest concert tour, traveling mostly on foot. In Hanover, he called on the violinist Joseph Joachim, who at twenty-two had just become the head of the royal court orchestra there and who was one of the finest violinists of the time. Joachim was so impressed by Brahms that he gave him a letter of introduction to Liszt in Weimar and sent him to see Schumann in Düsseldorf. Robert Schumann was then Germany’s leading composer, and his wife, Clara, was one of Europe’s greatest pianists. When they heard Brahms play, they took him into their home. Although this sonata purports to be Brahms’s Violin Sonata No. 1, according to the reflections of a student of Brahms, the composer had presumably discarded five violin sonatas that he had composed before he wrote this one, the first that he thought good enough to preserve and present to the world. -

Composer, Music Instructor, Choral Conductor

Dr. Joshua Fishbein, Ph.D. Composer, Music Instructor, Choral Conductor www.fishbeinmusic.com (412) 913-6584 [email protected] Education University of California, Los Angeles Graduated 2014 PhD in Music Composition Teachers: Roger Bourland, GPA: 4.0 overall Paul Chihara, Richard Danielpour, Graduate Assistantship Recipient Ian Krouse, and David Lefkowitz Dissertation: Leonard Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms: Assistantship/Fellowship Recipient an Analysis and Companion Piece Elaine Krown Klein Scholarship San Francisco Conservatory of Music Graduated 2009 Master of Music in Composition Teacher: Prof. David Conte GPA: 3.98 overall Scholarship/Assistantship Recipient University of Maryland, College Park, MD Fall 2006 – Spring 2007 (transferred) Graduate Study in Music Composition Teacher: Prof. Lawrence Moss GPA: 3.85 overall Graduate Assistantship Recipient Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA Graduated 2006 Bachelor of Fine Arts in Music (Composition) Teacher: Prof. Nancy Galbraith Bachelor of Science in Psychology Advisor: Prof. Lori Holt GPA: 3.9 overall, 4.0 within major. Science and Humanities Scholar Senior Project: Shoreside Melody for Orchestra (Winner, Harry G. Archer Prize in Orch. Comp.) Senior Honors Thesis: “Auditory Category Learning in Two Dimensions Across Time” Johns Hopkins Peabody Institute: The Preparatory Sept. 1999 – May 2002 Piano Performance, Music Theory Three Achievement Awards in Theory Piano Teacher: Carol Prochazka Music Theory Teacher: Stephen Coxe Teaching Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University Adjunct Faculty, Music Theory Arranging Spring 2019, Peabody at Homewood A newly designed course in arranging for vocal ensembles. Music Theory II Spring 2018, Peabody at Homewood A continuation of the study of melody, counterpoint and figured bass from Theory I, with special focus on chromatic harmony. -

A Note to BPO Patrons About the Passion of Yeshua

A Note to BPO Patrons about The Passion of Yeshua This coming weekend, April 13 and 14, the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra will present the east coast premiere of esteemed American composer Richard Danielpour’s new work, The Passion of Yeshua, following performances in Oregon and California. Mr. Danielpour is often lauded among the most gifted composers of his generation. His catalog is distinguished by more than forty commissions from a variety of major institutions, including the New York Philharmonic, the San Francisco Symphony, and the Philadelphia Orchestra, as well as for renowned performers such as Emanuel Ax, Yo-Yo Ma and Jessye Norman. Mr. Danielpour's honors include awards from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, a Guggenheim Award, the Bearns Prize from Columbia University, and two Rockefeller Fellowships. He currently serves as professor of composition at UCLA. A Passion is a musical setting of the suffering and death of Jesus of Nazareth, based upon Biblical texts which began to be composed in the 4th century and continue into modern times. Composers writing Passions include Alessandro Scarlatti, Marc-Antoine Charpentier, G.F. Handel, J.S. Bach, Krzysztof Penderecki among others. The BPO has performed the J.S. Bach St. Matthew Passion six times over the years, dating back to 1948 and his St. John Passion in 1964. However, there are concerns inherent in the presentation of such works due to differing views of history, beliefs and interpretation, so there is concern that such works can be viewed as anti-Semitic. The composer is well aware of history of Passions being used as weapons against the Jewish people but decided to use this musical form for the exact opposite reason. -

A Study of the Quintet for Piano and Strings by Richard Danielpour

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2004 A study of the Quintet for Piano and Strings by Richard Danielpour Myung Jin Kuh Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Kuh, Myung Jin, "A study of the Quintet for Piano and Strings by Richard Danielpour" (2004). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1093. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1093 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A STUDY OF THE QUINTET FOR PIANO AND STRINGS BY RICHARD DANIELPOUR A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Myung Jin Kuh B.M., Folkwang-Hochschule Essen (Germany), 1996 M.M., University of Missouri, 2000 August 2004 © Copyright 2004 Myung Jin Kuh All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my parents, Ja Ock Kuh and Won Young Yang, who have always encouraged and supported me throughout my years abroad. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my advisor, Professor Constance Carroll, for her guidance, patience, and encouragement throughout my doctoral studies with her. I also would like to thank the members of my committee, Professors David Smyth, Jennifer Hayghe, and Robert Peck for their valuable insights, suggestions, and corrections. -

Camerata Nova

Monday, October 5, 2020 | 12:15 PM Neidorff-Karpati Hall Live Streamed CAMERATA NOVA Kyle Ritenauer (BM ’11, MM ’15), Conductor PROGRAM TEXU KIM Dub-Stravinsky (2017) (b. 1980) IGOR ST R AVINSKY Suite from The Soldier’s Tale (L’Histoire du soldat) (1918) (1882–1971) The Soldier’s March Airs by a Stream Pastorale Royal March The Little Concert Three Dances: Tango – Waltz – Ragtime Dance of the Devil Grand Chorale Triumphal March of the Devil VALERIE COLEMAN Freedmen (of the Five Civilized Tribes) (2015) (b. 1970) REIKO FÜTING Weg, Lied der Schwäne (2015) (b. 1970) Der Weg Das Lied (Jacob Arcadelt: Il bianco e dolce cingo) CAMERATA NOVA FLUTE TRUMPET VIOLA PIANO Hyun Jo Lee Sean Alexander Sara Dudley Tamar Kutsnashvili Seong Nam, Korea Washington, D.C. New York, New York Tbilisi, Georgia CLARINET TROMBONE CELLO PERCUSSION Ki-Deok Park Eric Coughlin Somyong Shin Tarun Bellur* Chicago, Illinois Northborough, Massachusetts Gwanak-Gu, Korea Plano, Texas Arthur BASSOON VIOLIN DOUBLE BASS Dhuique-Mayer^+ Hunter Lorelli Xiaoxuan Shi Julian Barrera Paris, France Washington, D.C. Shanghai, China Fairview, New Jersey Percussion Principals *KIM Dub-Stravinsky ^ST R AVINSKY Suite from The Soldier’s Tale (L’Histoire du soldat) +FÜTING Weg, Lied der Schwäne ABOUT THE CONDUCTOR Kyle Ritenauer is a New York City-based conductor currently pursuing a degree at the Juilliard School as a student of David Robertson. Appearing regularly as a guest conductor in the area, Kyle recently led two performances with Carnegie Hall’s Ensemble Connect as a part of the Rite of Summer Festival. Kyle has also led multiple performances with the Norwalk Symphony Orchestra, the New Amsterdam Symphony Orchestra, Camerata Notturna, RIOULT Dance NY, and Manhattan School of Music. -

Juilliard Orchestra Jeffrey Milarsky , Conductor Brenden Zak , Violin

Thursday Evening, November 8, 2018, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents Juilliard Orchestra Jeffrey Milarsky , Conductor Brenden Zak , Violin AUGUSTA READ THOMAS (b. 1964) Prayer Bells LEONARD BERNSTEIN (1918 –90) Serenade (After Plato’s “Symposium”) Phaedras - Pausanias: Lento - Allegro Aristophanes: Allegretto Eryximachus: Presto Agathon: Adagio Socrates - Alcibiades: Molto tenuto - Allegro molto BRENDEN ZAK , Violin Intermission SERGEI PROKOFIEV (1891 –1953) Suite from Romeo and Juliet Montagues and Capulets The Young Juliet Romeo and Juliet Before Parting Romeo at Juliet’s Tomb Masks Balcony Scene Death of Tybalt Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 45 minutes, including one intermission The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. Notes on the Program Thomas composed Prayer Bells in 2001 on commission from the Pittsburgh Symphony by James M. Keller Orchestra and its conductor, Mariss Jansons, who presented its premiere on May 4 of Prayer Bells that year. She provided this comment AUGUSTA READ THOMAS about the piece: Born April 24, 1964, in Glen Cove, New York Currently residing in Chicago There is an indisputable journey taking place during the 12-minute composition. Augusta Read Thomas, who began com - In general the score falls into a three-part posing as a child, has become one of the form: a slow-growing introduction of 90 most admired and fêted of her generation seconds (which is a section of music I of American composers.