Scene on Radio on Crazy We Built a Nation (Seeing White, Part 4) Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20 Thomas Jefferson.Pdf

d WHAT WE THINK ABOUT WHEN WE THINK ABOUT THOMAS JEFFERSON Todd Estes Thomas Jefferson is America’s most protean historical figure. His meaning is ever-changing and ever-changeable. And in the years since his death in 1826, his symbolic legacy has varied greatly. Because he was literally present at the creation of the Declaration of Independence that is forever linked with him, so many elements of subsequent American life—good and bad—have always attached to Jefferson as well. For a quarter of a century—as an undergraduate, then a graduate student, and now as a professor of early American his- tory—I have grappled with understanding Jefferson. If I have a pretty good handle on the other prominent founders and can grasp the essence of Washington, Madison, Hamilton, Adams and others (even the famously opaque Franklin), I have never been able to say the same of Jefferson. But at least I am in good company. Jefferson biographer Merrill Peterson, who spent a scholarly lifetime devoted to studying him, noted that of his contemporaries Jefferson was “the hardest to sound to the depths of being,” and conceded, famously, “It is a mortifying confession but he remains for me, finally, an impenetrable man.” This in the preface to a thousand page biography! Pe- terson’s successor as Thomas Jefferson Foundation Professor at Mr. Jefferson’s University of Virginia, Peter S. Onuf, has noted the difficulty of knowing how to think about Jefferson 21 once we sift through the reams of evidence and confesses “as I always do when pressed, that I am ‘deeply conflicted.’”1 The more I read, learn, write, and teach about Jefferson, the more puzzled and conflicted I remain, too. -

Thomas Jefferson and the Ideology of Democratic Schooling

Thomas Jefferson and the Ideology of Democratic Schooling James Carpenter (Binghamton University) Abstract I challenge the traditional argument that Jefferson’s educational plans for Virginia were built on mod- ern democratic understandings. While containing some democratic features, especially for the founding decades, Jefferson’s concern was narrowly political, designed to ensure the survival of the new republic. The significance of this piece is to add to the more accurate portrayal of Jefferson’s impact on American institutions. Submit your own response to this article Submit online at democracyeducationjournal.org/home Read responses to this article online http://democracyeducationjournal.org/home/vol21/iss2/5 ew historical figures have undergone as much advocate of public education in the early United States” (p. 280). scrutiny in the last two decades as has Thomas Heslep (1969) has suggested that Jefferson provided “a general Jefferson. His relationship with Sally Hemings, his statement on education in republican, or democratic society” views on Native Americans, his expansionist ideology and his (p. 113), without distinguishing between the two. Others have opted suppressionF of individual liberties are just some of the areas of specifically to connect his ideas to being democratic. Williams Jefferson’s life and thinking that historians and others have reexam- (1967) argued that Jefferson’s impact on our schools is pronounced ined (Finkelman, 1995; Gordon- Reed, 1997; Kaplan, 1998). because “democracy and education are interdependent” and But his views on education have been unchallenged. While his therefore with “education being necessary to its [democracy’s] reputation as a founding father of the American republic has been success, a successful democracy must provide it” (p. -

Sovereignty of the Living Individual: Emerson and James on Politics and Religion

religions Article Sovereignty of the Living Individual: Emerson and James on Politics and Religion Stephen S. Bush Department of Religious Studies, Brown University, 59 George Street, Providence, RI 02912, USA; [email protected] Received: 20 July 2017; Accepted: 20 August 2017; Published: 25 August 2017 Abstract: William James and Ralph Waldo Emerson are both committed individualists. However, in what do their individualisms consist and to what degree do they resemble each other? This essay demonstrates that James’s individualism is strikingly similar to Emerson’s. By taking James’s own understanding of Emerson’s philosophy as a touchstone, I argue that both see individualism to consist principally in self-reliance, receptivity, and vocation. Putting these two figures’ understandings of individualism in comparison illuminates under-appreciated aspects of each figure, for example, the political implications of their individualism, the way that their religious individuality is politically engaged, and the importance of exemplarity to the politics and ethics of both of them. Keywords: Ralph Waldo Emerson; William James; transcendentalism; individualism; religious experience 1. Emersonian Individuality, According to James William James had Ralph Waldo Emerson in his bones.1 He consumed the words of the Concord sage, practically from birth. Emerson was a family friend who visited the infant James to bless him. James’s father read Emerson’s essays out loud to him and the rest of the family, and James himself worked carefully through Emerson’s corpus in the 1870’s and then again around 1903, when he gave a speech on Emerson (Carpenter 1939, p. 41; James 1982, p. 241). -

The Causes of the American Revolution

Page 50 Chapter 12 By What Right Thomas Hobbes John Locke n their struggle for freedom, the colonists raised some age-old questions: By what right does government rule? When may men break the law? I "Obedience to government," a Tory minister told his congregation, "is every man's duty." But the Reverend Jonathan Boucher was forced to preach his sermon with loaded pistols lying across his pulpit, and he fled to England in September 1775. Thomas Jefferson wrote in the Declaration of Independence that when people are governed "under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such a Government." Both Boucher and Jefferson spoke to the question of whether citizens owe obedience to government. In an age when kings held near absolute power, people were told that their kings ruled by divine right. Disobedience to the king was therefore disobedience to God. During the seventeenth century, however, the English beheaded one King (King Charles I in 1649) and drove another (King James II in 1688) out of England. Philosophers quickly developed theories of government other than the divine right of kings to justify these actions. In order to understand the sources of society's authority, philosophers tried to imagine what people were like before they were restrained by government, rules, or law. This theoretical condition was called the state of nature. In his portrait of the natural state, Jonathan Boucher adopted the opinions of a well- known English philosopher, Thomas Hobbes. Hobbes believed that humankind was basically evil and that the state of nature was therefore one of perpetual war and conflict. -

Life, Liberty, and . . .: Jefferson on Property Rights

Journal of Libertarian Studies Volume 18, no. 1 (Winter 2004), pp. 31–87 2004 Ludwig von Mises Institute www.mises.org LIFE, LIBERTY, AND . : JEFFERSON ON PROPERTY RIGHTS Luigi Marco Bassani* Property does not exist because there are laws, but laws exist because there is property.1 Surveys of libertarian-leaning individuals in America show that the intellectual champions they venerate the most are Thomas Jeffer- son and Ayn Rand.2 The author of the Declaration of Independence is an inspiring source for individuals longing for liberty all around the world, since he was a devotee of individual rights, freedom of choice, limited government, and, above all, the natural origin, and thus the inalienable character, of a personal right to property. However, such libertarian-leaning individuals might be surprised to learn that, in academic circles, Jefferson is depicted as a proto-soc- ialist, the advocate of simple majority rule, and a powerful enemy of the wicked “possessive individualism” that permeated the revolution- ary period and the early republic. *Department Giuridico-Politico, Università di Milano, Italy. This article was completed in the summer of 2003 during a fellowship at the International Center for Jefferson Studies, Monticello, Va. I gladly acknowl- edge financial support and help from such a fine institution. luigi.bassani@ unimi.it. 1Frédéric Bastiat, “Property and Law,” in Selected Essays on Political Econ- omy, trans. Seymour Cain, ed. George B. de Huszar (Irvington-on-Hudson, N.Y.: Foundation for Economic Education, 1964), p. 97. 2E.g., “The Liberty Poll,” Liberty 13, no. 2 (February 1999), p. 26: “The thinker who most influenced our respondents’ intellectual development was Ayn Rand. -

JACQUES ROUSSEAU's EMILE By

TOWARD AN UNDERSTANDING OF THE NOVELISTIC DIMENSION OF JEAN- JACQUES ROUSSEAU’S EMILE by Stephanie Miranda Murphy A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science University of Toronto © Copyright by Stephanie Miranda Murphy 2020 Toward an Understanding of the Novelistic Dimension of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Emile Stephanie Miranda Murphy Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science ABSTRACT The multi-genre combination of philosophic and literary expression in Rousseau’s Emile provides an opportunity to explore the relationship between the novelistic structure of this work and the substance of its philosophical teachings. This dissertation explores this matter through a textual analysis of the role of the novelistic dimension of the Emile. Despite the vast literature on Rousseau’s manner of writing, critical aspects of the novelistic form of the Emile remain either misunderstood or overlooked. This study challenges the prevailing image in the existing scholarship by arguing that Rousseau’s Emile is a prime example of how form and content can fortify each other. The novelistic structure of the Emile is inseparable from Rousseau’s conception and communication of his philosophy. That is, the novelistic form of the Emile is not simply harmonious with the substance of its philosophical content, but its form and content also merge to reinforce Rousseau’s capacity to express his teachings. This dissertation thus proposes to demonstrate how and why the novelistic -

Political Legacy: John Locke and the American Government

POLITICAL LEGACY: JOHN LOCKE AND THE AMERICAN GOVERNMENT by MATTHEW MIYAMOTO A THESIS Presented to the Department of Political Science and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science January 2016 An Abstract of the Thesis of Matthew Miyamoto for the degree of Bachelor of Science in the Department of Political Science to be taken January, 2016 Title: Political Legacy: John Locke and the American Government Professor Dan Tichenor John Locke, commonly known as the father of classical liberalism, has arguably influenced the United States government more than any other political philosopher in history. His political theories include the quintessential American ideals of a right to life, liberty, and property, as well as the notion that the government is legitimized through the consent of the governed. Locke's theories guided the founding fathers through the creation of the American government and form the political backbone upon which this nation was founded. His theories form the foundation of principal American documents such as the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights, and they permeate the speeches, writings, and letters of our founding fathers. Locke's ideas define our world so thoroughly that we take them axiomatically. Locke's ideas are our tradition. They are our right. This thesis seeks to understand John Locke's political philosophy and the role that he played in the creation of the United States government. .. 11 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professor Dan Tichenor for helping me to fully examine this topic and guiding me through my research and writing. -

The Abolition of Emerson: the Secularization of America’S Poet-Priest and the New Social Tyranny It Signals

THE ABOLITION OF EMERSON: THE SECULARIZATION OF AMERICA’S POET-PRIEST AND THE NEW SOCIAL TYRANNY IT SIGNALS A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government By Justin James Pinkerman, M.A. Washington, DC February 1, 2019 Copyright 2019 by Justin James Pinkerman All Rights Reserved ii THE ABOLITION OF EMERSON: THE SECULARIZATION OF AMERICA’S POET-PRIEST AND THE NEW SOCIAL TYRANNY IT SIGNALS Justin James Pinkerman, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Dr. Richard Boyd, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Motivated by the present climate of polarization in US public life, this project examines factional discord as a threat to the health of a democratic-republic. Specifically, it addresses the problem of social tyranny, whereby prevailing cultural-political groups seek to establish their opinions/sentiments as sacrosanct and to immunize them from criticism by inflicting non-legal penalties on dissenters. Having theorized the complexion of factionalism in American democracy, I then recommend the political thought of Ralph Waldo Emerson as containing intellectual and moral insights beneficial to the counteraction of social tyranny. In doing so, I directly challenge two leading interpretations of Emerson, by Richard Rorty and George Kateb, both of which filter his thought through Friedrich Nietzsche and Walt Whitman and assimilate him to a secular-progressive outlook. I argue that Rorty and Kateb’s political theories undercut Emerson’s theory of self-reliance by rejecting his ethic of humility and betraying his classically liberal disposition, thereby squandering a valuable resource to equip individuals both to refrain from and resist social tyranny. -

More- EXHIBITION HIGHLIGHTS ICONIC IMAGES of AMERICANS: Houdon's Portraits of Great American Leaders and Thinkers of the Enli

EXHIBITION HIGHLIGHTS ICONIC IMAGES OF AMERICANS: Houdon’s portraits of great American leaders and thinkers of the Enlightenment reflect the close ties between France and the United States during and after the Revolutionary War. His depictions of America’s founders created lasting images that are widely reproduced to this day. • Thomas Jefferson (1789) is a marble bust that has literally shaped the world’s image of Jefferson, portraying him as a sensitive, intellectual, aristocratic statesman with a resolute, determined gaze. This sculpture has served as the model for numerous other portraits of Jefferson, including the profile on the modern American nickel. Jefferson considered Houdon the finest sculptor of his day, and acquired several of the artist’s busts of famous men—including Washington, Franklin, John Paul Jones, Lafayette, and Voltaire—to create a “gallery of worthies” at his home, Monticello, in Virginia. He sat for his own portrait at Houdon’s studio in Paris in 1789 at the age of 46. This piece is on loan from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. • George Washington (late 1780s), a portrait of America’s first president, is a marble bust, one of several Washington portraits created by Houdon. The most famous, and considered by Houdon to be the most important commission of his career, is the full-length statue of Washington that commands the rotunda of the capitol building of the State of Virginia. Both Jefferson and Franklin recommended Houdon for the commission, and the sculptor traveled with Franklin from Paris to Mount Vernon in 1785 to visit Washington, make a life mask, and take careful measurements. -

The Jeffersonian Jurist? a R Econsideration of Justice Louis Brandeis and the Libertarian Legal Tradition in the United States I

MENDENHALL_APPRVD.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 5/14/17 3:27 PM THE JEFFERSONIAN JURIST? A RECONSIDERATION OF JUSTICE LOUIS BRANDEIS AND THE LIBERTARIAN LEGAL TRADITION IN THE UNITED STATES * BY ALLEN MENDENHALL I. BRANDEIS AND LIBERTARIANISM ..................................................... 285 II. IMPLICATIONS AND EFFECTS OF CLASSIFYING BRANDEIS AS A LIBERTARIAN .............................................................................. 293 III. CONCLUSION ................................................................................... 306 The prevailing consensus seems to be that Justice Louis D. Brandeis was not a libertarian even though he has long been designated a “civil libertarian.”1 A more hardline position maintains that Brandeis was not just non-libertarian, but an outright opponent of “laissez-faire jurisprudence.”2 Jeffrey Rosen’s new biography, Louis D. Brandeis: American Prophet, challenges these common understandings by portraying Brandeis as “the most important American critic of what he called ‘the curse of bigness’ in government and business since Thomas Jefferson,”3 who was a “liberty-loving” man preaching “vigilance against * Allen Mendenhall is Associate Dean at Faulkner University Thomas Goode Jones School of Law and Executive Director of the Blackstone & Burke Center for Law & Liberty. Visit his website at AllenMendenhall.com. He thanks Ilya Shapiro and Josh Blackman for advice and Alexandra SoloRio for research assistance. Any mistakes are his alone. 1 E.g., KEN L. KERSCH, CONSTRUCTING CIVIL LIBERTIES: DISCONTINUITIES IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF AMERICAN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 112 (Cambridge Univ. Press 2004); LOUIS MENAND, THE METAPHYSICAL CLUB: A STORY OF IDEAS IN AMERICA 66 (Farrar, Straus & Giroux 2001); David M. Rabban, The Emergence of Modern First Amendment Doctrine, 50 U. CHI. L. REV. 1205, 1212 (1983); Howard Gillman, Regime Politics, Jurisprudential Regimes, and Unenumerated Rights, 9 U. -

Lesson Plan Template

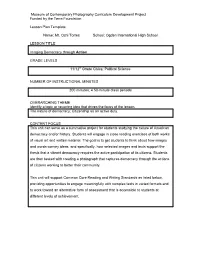

Museum of Contemporary Photography Curriculum Development Project Funded by the Terra Foundation Lesson Plan Template Name: Mr. Ozni Torres School: Ogden International High School LESSON TITLE Imaging Democracy through Action GRADE LEVELS 11/12th Grade Civics; Political Science NUMBER OF INSTRUCTIONAL MINUTES 200 minutes; 4 50-minute class periods OVERARCHING THEME Identify a topic or recurring idea that drives the focus of the lesson. The nature of democracy; Citizenship as an active duty. CONTENT FOCUS This unit can serve as a summative project for students studying the nature of American democracy and/or history. Students will engage in close reading exercises of both works of visual art and written material. The goal is to get students to think about how images and words convey ideas, and specifically, how selected images and texts support the thesis that a vibrant democracy requires the active participation of its citizens. Students are then tasked with creating a photograph that captures democracy through the actions of citizens working to better their community. This unit will support Common Core Reading and Writing Standards as listed below, providing opportunities to engage meaningfully with complex texts in varied formats and to work toward an alternative form of assessment that is accessible to students at different levels of achievement. Museum of Contemporary Photography Curriculum Development Project Funded by the Terra Foundation ART ANALYSIS List the names of artist(s) and titles of their artwork that students will do close reading exercises on. Artist Work of Art John Trumbull 12’ X 18’ 1818 Rotunda; U.S. Capitol D eclaration of Independence Paul Shambroom 2’9” X 5’6” 1999 Museum of Contemporary Photography Markl e, IN (pop. -

ED331751.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 331 751 SO 020 969 AUTHOR Brooks, B. David TITLE Success through Accepting Responsibility. Principal's Handbook: Creating a School Climate of Responsibility. Revised Edition. INSTITUTION Thomas Jefferson Research Center, Pasadena, Calif. PUB DATE 89 NOTE 130p. AVAILABLE FROM Thomas Jefferson Research Center, 202 South Lake Avenue, Suite 240, Pasadena, CA 91101. PUB TYPE Guides - Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Administrator Guides; *Administrator Role; Citizenship Education; *Educational Environment; Educational Planning; Elementary Secondary Education; Ethics; *pri4cipals; School Activities; Self Esteem; Skill Development; Social Responsibility; Social Studies; *Student Educational Objectives; *Student Responsibility; *Success; Values; Vocabulary Development ABSTRACT Success Through Accepting Responsibility (STAR)is primarily a language program, although the valueshave a relationship to social studies topics. Through language developmentthe words, concepts, and skills of personal responsibilitymay be taught. This principal's handbook outlines a school-wide systematicapproach for building a positive school climate around self-esteemand personal responsibility. Following an introduction, the handbookis organized into eight sections: planning and implementation;kick-off activities; year-long activities; sustainingevents and activities; end-of-year activities; parent and communityinvolvement; evaluations and reports; and principal's memos. (DB) ** ***** ****************************************************************