ODIFE, Ikenna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interim Capacity Building for Operators of Microfinance Banks

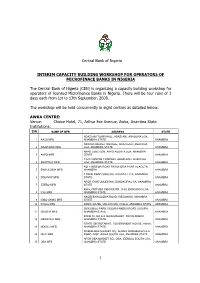

Central Bank of Nigeria INTERIM CAPACITY BUILDING WORKSHOP FOR OPERATORS OF MICROFINACE BANKS IN NIGERIA The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) is organizing a capacity building workshop for operators of licensed Microfinance Banks in Nigeria. There will be four runs of 3 days each from 1st to 13th September, 2008. The workshop will be held concurrently in eight centres as detailed below: AWKA CENTRE: Venue: Choice Hotel, 71, Arthur Eze Avenue, Awka, Anambra State. Institutions: S/N NAME OF MFB ADDRESS STATE ADAZI ANI TOWN HALL, ADAZI ANI, ANAOCHA LGA, 1 AACB MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NKWOR MARKET SQUARE, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 2 ADAZI-ENU MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA AKPO JUNCTION, AKPO AGUATA LGA, ANAMBRA 3 AKPO MFB STATE ANAMBRA CIVIC CENTRE COMPLEX, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 4 BESTWAY MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NO 1 MISSION ROAD EKWULOBIA P.M.B.24 AGUTA, 5 EKWULOBIA MFB ANAMBRA ANAMBRA 1 BANK ROAD UMUCHU, AGUATA L.G.A, ANAMBRA 6 EQUINOX MFB STATE ANAMBRA AFOR IGWE UMUDIOKA, DUNUKOFIA LGA, ANAMBRA 7 EZEBO MFB STATE ANAMBRA KM 6, ONITHSA OKIGWE RD., ICHI, EKWUSIGO LGA, 8 ICHI MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NNOBI/EKWULOBIA ROAD, IGBOUKWU, ANAMBRA 9 IGBO-UKWU MFB STATE ANAMBRA 10 IHIALA MFB BANK HOUSE, ORLU ROAD, IHIALA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA EKWUSIGO PARK, ISUOFIA-NNEWI ROAD, ISUOFIA, 11 ISUOFIA MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA ZONE 16, NO.6-9, MAIN MARKET, NKWO-NNEWI, 12 MBAWULU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA STATE SECRETARIAT, GOVERNMENT HOUSE, AWKA, 13 NDIOLU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NGENE-OKA MARKET SQ., ALONG AMAWBIA/AGULU 14 NICE MFB ROAD, NISE, AWKA SOUTH -

Research Report

1.1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Soil erosion is the systematic removal of soil, including plant nutrients, from the land surface by various agents of denudation (Ofomata, 1985). Water being the dominant agent of denudation initiates erosion by rain splash impact, drag and tractive force acting on individual particles of the surface soil. These are consequently transported seizing slope advantage for deposition elsewhere. Soil erosion is generally created by initial incision into the subsurface by concentrated runoff water along lines or zones of weakness such as tension and desiccation fractures. As these deepen, the sides give in or slide with the erosion of the side walls forming gullies. During the Stone Age, soil erosion was counted as a blessing because it unearths valuable treasures which lie hidden below the earth strata like gold, diamond and archaeological remains. Today, soil erosion has become an endemic global problem, In the South eastern Nigeria, mostly in Anambra State, it is an age long one that has attained a catastrophic dimension. This environmental hazard, because of the striking imprints on the landscape, has sparked off serious attention of researchers and government organisations for sometime now. Grove(1951); Carter(1958); Floyd(1965); Ofomata (1964,1965,1967,1973,and 1981); all made significant and refreshing contributions on the processes and measures to combat soil erosion. Gully Erosion is however the prominent feature in the landscape of Anambra State. The topography of the area as well as the nature of the soil contributes to speedy formation and spreading of gullies in the area (Ofomata, 2000);. 1.2 Erosion Types There are various types of erosion which occur these include Soil Erosion Rill Erosion Gully Erosion Sheet Erosion 1.2.1 Soil Erosion: This has been occurring for some 450 million years, since the first land plants formed the first soil. -

New Projects Inserted by Nass

NEW PROJECTS INSERTED BY NASS CODE MDA/PROJECT 2018 Proposed Budget 2018 Approved Budget FEDERAL MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL SUPPLYFEDERAL AND MINISTRY INSTALLATION OF AGRICULTURE OF LIGHT AND UP COMMUNITYRURAL DEVELOPMENT (ALL-IN- ONE) HQTRS SOLAR 1 ERGP4145301 STREET LIGHTS WITH LITHIUM BATTERY 3000/5000 LUMENS WITH PIR FOR 0 100,000,000 2 ERGP4145302 PROVISIONCONSTRUCTION OF SOLAR AND INSTALLATION POWERED BOREHOLES OF SOLAR IN BORHEOLEOYO EAST HOSPITALFOR KOGI STATEROAD, 0 100,000,000 3 ERGP4145303 OYOCONSTRUCTION STATE OF 1.3KM ROAD, TOYIN SURVEYO B/SHOP, GBONGUDU, AKOBO 0 50,000,000 4 ERGP4145304 IBADAN,CONSTRUCTION OYO STATE OF BAGUDU WAZIRI ROAD (1.5KM) AND EFU MADAMI ROAD 0 50,000,000 5 ERGP4145305 CONSTRUCTION(1.7KM), NIGER STATEAND PROVISION OF BOREHOLES IN IDEATO NORTH/SOUTH 0 100,000,000 6 ERGP445000690 SUPPLYFEDERAL AND CONSTITUENCY, INSTALLATION IMO OF STATE SOLAR STREET LIGHTS IN NNEWI SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 7 ERGP445000691 TOPROVISION THE FOLLOWING OF SOLAR LOCATIONS: STREET LIGHTS ODIKPI IN GARKUWARI,(100M), AMAKOM SABON (100M), GARIN OKOFIAKANURI 0 400,000,000 8 ERGP21500101 SUPPLYNGURU, YOBEAND INSTALLATION STATE (UNDER OF RURAL SOLAR ACCESS STREET MOBILITY LIGHTS INPROJECT NNEWI (RAMP)SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 9 ERGP445000692 TOSUPPLY THE FOLLOWINGAND INSTALLATION LOCATIONS: OF SOLAR AKABO STREET (100M), LIGHTS UHUEBE IN AKOWAVILLAGE, (100M) UTUH 0 500,000,000 10 ERGP445000693 ANDEROSION ARONDIZUOGU CONTROL IN(100M), AMOSO IDEATO - NCHARA NORTH ROAD, LGA, ETITI IMO EDDA, STATE AKIPO SOUTH LGA 0 200,000,000 11 ERGP445000694 -

List of Coded Health Facilities in Anambra State.Pdf

Anambra State Health Facility Listing LGA WARD NAME OF HEALTH FACILITY FACILITY TYPE OWERSHIP CODE (PUBLIC/ PRIVATE) LGA STATE OWERSHIP FACILITYTYPE FACILITYNUMBER Primary Health Centre Oraeri Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0001 Primary Health Centre Akpo Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0002 Ebele Achina PHC Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0003 Primary Health Centre Aguata Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0004 Primary Health Centre Ozala Isuofia Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0005 Primary Health Centre Uga Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0006 Primary Health Centre Mkpologwu Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0007 Primary Health Centre Ikenga Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0008 Health Centre Ekwusigo Isuofia Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0009 Primary Health Centre Amihie Umuchu Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0010 Obimkpa Achina Health Centre Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0011 Primary Health Centre Amesi Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0012 Primary Health Centre Ezinifite Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0013 Primary Health Centre Ifite Igboukwu Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0014 Health Post Amesi Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0015 Isiaku Health Post Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0016 Analasi Uga Health Post Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0017 Ugwuakwu Umuchu Health Post Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0018 Aguluezechukwu Health Post Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0019 Health Centre Umuona Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0020 Health Post Akpo Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0021 Health Center, Awa Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0022 General Hospital Ekwuluobia Secondary Public 04 01 1 1 0023 General Hospital Umuchu Secondary Public 04 01 2 1 0024 Comprehensive Health Centre Achina Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0025 Catholic Visitation Hospital, Umuchu Secondary Private 04 01 2 2 0026 Continental Hospital Ekwulobia Primary Private 04 01 1 2 0027 Niger Hospital Igboukwu Primary Private 04 01 1 2 0028 Dr. -

State: Anambra Code: 04

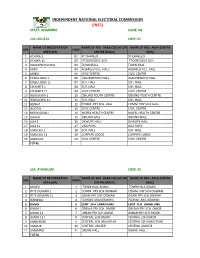

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: ANAMBRA CODE: 04 LGA :AGUATA CODE: 01 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ACHINA 1 01 ST CHARLED ST CHARLED 2 ACHINA 11 02 PTOGRESSIVE SCH. PTOGRESSIVE SCH. 3 AGULEZECHUKWU 03 TOWN HALL TOWN HALL 4 AKPO 04 AGBAELU VILL. HALL AGBAELU VILL. HALL 5 AMESI 05 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE 6 EKWULOBIA 1 06 UMUEZENOFO HALL. UMUEZENOFO HALL. 7 EKWULOBIA 11 07 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 8 EZENIFITE 1 08 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 9 EZENIFITE 11 09 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE 10 IGBOUKWU 1 10 OBIUNO YOUTH CENTRE OBIUNO YOUTH CENTRE 11 IGBOUKWU 11 11 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 12 IKENGA 12 COMM. PRY SCH. HALL COMM. PRY SCH. HALL 13 ISUOFIA 13 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE 14 NKPOLOGWU 14 MOFEL HEALTH CENTRE MOFEL HEALTH CENTRE 15 ORAERI 15 OBIUNO HALL OBIUNO HALL 16 UGA 1 16 OKWUTE HALL OKWUTE HALL 17 UGA 11 17 UGA BOYS UGA BOYS 18 UMUCHU 1 18 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 19 UMUCHU 11 19 CORPERS LODGE CORPERS LODGE 20 UMOUNA 20 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE TOTAL LGA: AYAMELUM CODE: 02 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ANAKU 1 TOWN HALL ANAKU TOWN HALL ANAKU 2 IFITE OGWARI 1 2 COMM. PRY SCH.OGWARI COMM. PRY SCH.OGWARI 3 IFITE OGWARI 11 3 OGARI PRY SCH.OGWARI OGARI PRY SCH.OGWARI 4 IGBAKWU 4 ISIOKWE ARA,IGBAKWU ISIOKWE ARA,IGBAKWU 5 OMASI 5 CENT. -

Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No

LICENSED MICROFINANCE BANKS (MFBs) IN NIGERIA AS AT SEPTEMBER 22, 2017 # Name Category Address State Description 1 AACB Microfinance Bank Limited State Nnewi/ Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No. 9 Oba Akran Avenue, Ikeja Lagos State. LAGOS 3 Abatete Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Abatete Town, Idemili Local Govt Area, Anambra State ANAMBRA 4 ABC Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Mission Road, Okada, Edo State EDO 5 Abestone Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Commerce House, Beside Government House, Oke Igbein, Abeokuta, Ogun State OGUN 6 Abia State University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Uturu, Isuikwuato LGA, Abia State ABIA 7 Abigi Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 28, Moborode Odofin Street, Ijebu Waterside, Ogun State OGUN 8 Abokie Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Plot 2, Murtala Mohammed Square, By Independence Way, Kaduna State. KADUNA 9 Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University (ATBU), Yelwa Road, Bauchi Bauchi 10 Abucoop Microfinance Bank Limited State Plot 251, Millenium Builder's Plaza, Hebert Macaulay Way, Central Business District, Garki, Abuja ABUJA 11 Accion Microfinance Bank Limited National 4th Floor, Elizade Plaza, 322A, Ikorodu Road, Beside LASU Mini Campus, Anthony, Lagos LAGOS 12 ACE Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 3, Daniel Aliyu Street, Kwali, Abuja ABUJA 13 Acheajebwa Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Sarkin Pawa Town, Muya L.G.A Niger State NIGER 14 Achina Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Achina Aguata LGA, Anambra State ANAMBRA 15 Active Point Microfinance Bank Limited State 18A Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State AKWA IBOM 16 Acuity Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 167, Adeniji Adele Road, Lagos LAGOS 17 Ada Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Agwada Town, Kokona Local Govt. -

Eastern Anambra Basin and Underlain by the Coastal Plain Sands (Miocene to Pleistocene), Ameki Formation (Eocene), and Ogwashi Asaba Formation (Oligocene to Miocene)

CJPS COOU Journal of Physical sciences 2(8),2019 COOU RESERVE ESTIMATIONS AND ECONOMIC POTENTIALS OF EXPOSED KAOLIN OUTCROPS IN PARTS OF SOUTH- EASTERNANAMBRA BASIN, ANAMBRA STATE, NIGERIA OBINEGBU, I.R, AND CHIAGHANAM, O.I Department of Geology, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Uli, Anambra State ABSTRACT: The study area covers parts of Ukpor, Okija, Ozubulu, Orsumoghu, Lilu, Ihiala and environs. The area is located in the Southeastern Anambra Basin and underlain by the Coastal Plain Sands (Miocene to Pleistocene), Ameki Formation (Eocene), and Ogwashi Asaba Formation (Oligocene to Miocene). In this research, the reserve estimations and economic potentials of the exposed kaolin deposits in parts of Southeastern Anambra Basin in Anambra State of Nigeria with that of Nothern Benue Trough kaolin deposits used for comparison were studied. All the Kaolin deposits in the study area, were hosted in Ogwashi-Asaba Formation. The Kaolin samples were collected from the exposed outcrops in the study area. They were using Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy. The oxides detected from the analysis include: SiO2, Al2O3, Fe2O3, TiO2, CaO, MgO, Na2O, K2O, MnO, CuO, ZnO, Cr2O5, V205 and the major oxides of Kaolins from the study areas shows that Si02 (50.74% to 58.24%) and Al203 (23.48% to 32.21%) constitute over 75% of the bulk chemical compositions. The high content of Si02 shows that the source rocks are silica rich minerals resulting in the grittiness of the kaolin, while other oxides are present in relatively very small amounts. The occurrence of Ca0, Na0 and K20 which are the major components of feldspars in clay suggest the kaolin to be of granitic origin, possibly from Oban massif, east of the Anambra Basin. -

Geotechnical Characterization of Lateritic Soils of Parts of Anambra State Southeast, Nigeria As Base Materials

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 10, Issue 8, August-2019 68 ISSN 2229-5518 GEOTECHNICAL CHARACTERIZATION OF LATERITIC SOILS OF PARTS OF ANAMBRA STATE SOUTHEAST, NIGERIA AS BASE MATERIALS. By *Ogechukwu Ben-Owope, *Elizabeth Okoyeh, **Eunice Okeke, **Florence Ilechukwu *Dept. of Geological Sciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe University Awka, Nigeria. **Anambra State Materials Testing Laboratory Awka, Nigeria. Email: [email protected] , [email protected] Abstract Twelve samples were collected from different locations in Anambra State for evaluation as base material for road construction. The samples were tested for specific gravity, particle size distribution, atteberg limit, linear shrinkage, compaction and california bearing capacity. The result of the specific gravity test ranges from 2.35Mg/m3 - 2.63Mg/m3 while the values of the particle size distribution test ranges from 13% and 36% making only sample S8 unsuitable for use as base material. The samples revealed the following range of values for atterberg limit properties: Liquid Limit 22% to 44%; Plastic Limit 10% to23%; Plasticity Index 12% to 24%; Linear Shrinkage 7% to 11%. AASHTO soil classification system identified S8 as A-7(poor), S9 and S12 as A-2-7 (good) while others are A-2-6(good) samples. M.D.D values obtained from compaction parameters range from 1.96 Mg/m3 to 2.24 Mg/m3 and O.M.C as 7.44% to 14.67% while the California Bearing Ratio (unsoaked) ranges from 76% to 113%. Based on the Nigerian Federal Ministry of Works and Housing specification (NFMWH), samples S1, S6 and S8 are only suitable for sub-base while samples S2, S3, S4, S5, S7, S9, S10, S11 and S12 are suitable for both sub- base and base- course. -

Praise Names and Power De/Constructions in Contemporary Igbo Chiefship O B O D O D I M M a O H a U N I V E R S I T Y O F I B a D a N

CULTURA, LENGUAJE Y REPRESENTACIÓN / CULTURE, LANGUAGE AND REPRESENTATION ˙ ISSN 1697-7750 · VOL VII \ 2009, pp. 101-116 REVISTA DE ESTUDIOS CULTURALES DE LA UNIVERSITAT JAUME I / CULTURAL STUDIES JOURNAL OF UNIVERSITAT JAUME I Praise Names and Power De/constructions in Contemporary Igbo Chiefship OBODODIMMA OHA UNIVER S ITY OF IBADAN ABSTRACT: Praise names are very important means through which individuals in the Igbo society generally articulate and express their ideologies, boast about their abilities and accomplishments, as well as criticize and subvert the visions of the Other. With particular reference to chieftaincy in the Igbo society, praise-naming as a pragma-semiotic act ties up with constructions and deconstructions of power, and so does have serious implications for the meanings attached to chieftaincy, as well as the roles of the chief in the postcolonial democratic system. The present paper therefore discusses the semiotics of praise names in the contemporary Igbo society, drawing data from popular culture and chieftaincy discourses. It addresses the interface between signification and politics (and the politics of signification) in Africa, arguing that change in the understanding and relevance of chieftaincy in postcolonial Africa calls for attention to how chieftaincy is (re)staged at the site of the sign. Keywords: Praise name, Chief, politics, power, Igbo. RESUMEN: Los nombres laudatorios constituyen un importante medio a través del cual los individuos de la sociedad Igbo articulan y expresan sus ideologías, se vanaglorian de sus logros y critican, así como subvierten las representaciones del Otro. En referencia a la figura del jefe tribal, los nombres laudatorios, en cuanto acto pragma-semiótico, se relacionan con la construcción y deconstrucción del poder, de lo que se derivan importantes implicaciones para el significado endosado al jefe tribal y sus roles en el sistema democrático poscolonial. -

A History of the Republic of Biafra

A History of the Republic of Biafra The Republic of Biafra lasted for less than three years, but the war over its secession would contort Nigeria for decades to come. Samuel Fury Childs Daly examines the history of the Nigerian Civil War and its aftermath from an uncommon vantage point – the courtroom. Wartime Biafra was glutted with firearms, wracked by famine, and administered by a government that buckled under the weight of the conflict. In these dangerous conditions, many people survived by engaging in fraud, extortion, and armed violence. When the fighting ended in 1970, these survival tactics endured, even though Biafra itself disappeared from the map. Based on research using an original archive of legal records and oral histories, Daly catalogues how people navigated conditions of extreme hardship on the war front and shows how the conditions of the Nigerian Civil War paved the way for the long experience of crime that followed. samuel fury childs daly is Assistant Professor of African and African American Studies, History, and International Comparative Studies at Duke University. A historian of twentieth-century Africa, he is the author of articles in journals including Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, African Studies Review, and African Affairs. A History of the Republic of Biafra Law, Crime, and the Nigerian Civil War samuel fury childs daly Duke University University Printing House, Cambridge CB2 8BS, United Kingdom One Liberty Plaza, 20th Floor, New York, NY 10006, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia 314 321, 3rd Floor, Plot 3, Splendor Forum, Jasola District Centre, New Delhi 110025, India 79 Anson Road, #06 04/06, Singapore 079906 Cambridge University Press is part of the University of Cambridge. -

List of First Bank Branches Nationwide

LIST OF FIRST BANK BRANCHES NATIONWIDE ABUJA FCT Abaji Branch Address 1: 1, Toto Road, Abaji Abuja FCT Abuja TelePhone : 09-7831250, 08130474233 Services : ATM, EWB, OB, MT Email : [email protected] Abuja Asokoro Branch Address 1: 85, Yakubu Gowon Crescent Asokoro, Abuja FCT Abuja TelePhone : 09-8723270-1, 87232, 08033326299, 080332 Services : ATM, ATM(24 Hrs), MT Email : Abuja Banex Plaza Branch Address 1: Banex Plaza, Plot 750 Aminu Kano Crescent, Wuse II Abuja FCT Abuja TelePhone : 09-4619600 , 46196, 08033355156, 08053 Services : ATM, ATM(24 Hrs), MT Email : Abuja Bwari Branch Address 1: Suleja Road, Bwari FCT Abuja TelePhone : 09-87238991, 09-870 Services : ATM, ATM(24 Hrs), MT Email : Abuja Dei Dei Market Branch Address 1: Abuja Regional Market FCT Abuja TelePhone : 09-7819704-6, 08060553885, 08025 Services : ATM, ATM(24 Hrs), MT Email : Abuja Garki Branch Address 1: Abuja Festival Road, Area 3, Garki FCT Abuja TelePhone : 09-2341070-3, 23446 Fax : 09-2341071 Services : ATM, ATM(24 Hrs), MT Email : Abuja Garki Modern Mkt Branch Address 1: Abuja Garki Modern Market, Garki, Abuja FCT Abuja TelePhone : 09- 7805724, 234013, 08052733252, 08023 Services : ATM, ATM(24 Hrs), MT Email : Abuja,Gwagwalada Branch Address 1: 5, Park Road, Off Abuja/Abaji Road, Gwagwalada, FCT, Abuja FCT Abuja TelePhone : 09-8820015, 8820033, 08027613509, 080553 Services : ATM, ATM(24 Hrs), MT Email : Abuja Jos Street Branch Address 1: Plot 451, Jos Street, Area 3, Garki FCT Abuja TelePhone : 09-2344724, 2343889, 08051000106, 08028 Services : ATM, ATM(24 Hrs), MT Email : Abuja, Karu Branch Address 1: Abuja-Keffi Road, Mararaba, Karu LGA, FCT, Abuja FCT Abuja TelePhone : 09 – 6703827, 67036, 08065303571, 080749 Services : ATM, ATM(24 Hrs), MT Email : Abuja Kubwa Branch Address 1: Plot B3, Gada Nasko Road, Opp. -

Spatial Statistics of Poultry Production in Anambra State of Nigeria: a Preliminary for Bio-Energy Plant Location Modelling

Nigerian Journal of Technology (NIJOTECH) Vol. 35, No. 4, October 2016, pp. 940 – 948 Copyright© Faculty of Engineering, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Print ISSN: 0331-8443, Electronic ISSN: 2467-8821 www.nijotech.com http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/njt.v35i4.32 SPATIAL STATISTICS OF POULTRY PRODUCTION IN ANAMBRA STATE OF NIGERIA: A PRELIMINARY FOR BIO-ENERGY PLANT LOCATION MODELLING E. C. Chukwuma1,*, L. C. Orakwe2, D. C. Anizoba3 and A. I. Manumehe4 1,2,3 DEPT. OF AGRIC. & BIORESOURCES ENGINEERING NNAMDI AZIKIWE UNIVERSITY, AWKA, ANAMBRA STATE, NIGERIA 4 NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL STANDARDS & REGULATIONS ENFORCEMENT AGENCY, AWKA, ANAMBRA STATE, NIGERIA E-mail addresses: 1 [email protected], 2 [email protected], 3 [email protected], 4 [email protected] ABSTRACT Consequent on the need to utilize bio-wastes for energy generation, a preliminary study for bio-energy plant location modelling was carried out in this work using spatial statistics technique in Anambra State of Nigeria as a case study. Spatial statistics toolbox in ArcGIS was used to generate point density map which reveal the regional patterns of biomass distribution and to generate hotspot analysis of zones of poultry production sites in the study area. The result of the study indicates that the central regions of the state is characterised with high point density poultry production sites, some of the locations with high point density poultry production values include: Ogbaru town which has the highest point density value of above 4,362,480kg of poultry droppings. This is followed by Umuchu, Onitsha, Nise, Nibo and Amawbia, with point density value that ranges from 2,210,250kg to 4,362,480kg.