Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders Hi, My Name Is Geraldine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOMATIC SYMPTOM, BODILY DISTRESS and RELATED DISORDERS in CHILDREN and ADOLESCENTS 2019 Edition

IACAPAP Textbook of Child and Adolescent Mental Health Chapter CHILD PSYCHIATRY & PEDIATRICS I.1 SOMATIC SYMPTOM, BODILY DISTRESS AND RELATED DISORDERS IN CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS 2019 edition Olivia Fiertag, Sharon Taylor, Amina Tareen & Elena Garralda Olivia Fiertag MBChB, MRCPsych, PGDip CBT Consultant Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist. Honorary Clinical Researcher, HPFT NHS Trust & collaboration with Imperial College London, UK Conflict of interest: none declared Sharon Taylor BSc, MBBS, MRCP, MRCPsych, CASLAT, PGDip Consultant Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist CNWL Foundation NHS Trust & Honorary Senior Clinical Lecturer Imperial College London, UK. Joint Program Director, St Mary’s Child Sick Girl. Psychiatry Training Scheme Christian Krogh, Conflict of interest: none (1880/1881) National declared Gallery of Norway This publication is intended for professionals training or practicing in mental health and not for the general public. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Editor or IACAPAP. This publication seeks to describe the best treatments and practices based on the scientific evidence available at the time of writing as evaluated by the authors and may change as a result of new research. Readers need to apply this knowledge to patients in accordance with the guidelines and laws of their country of practice. Some medications may not be available in some countries and readers should consult the specific drug information since not all dosages and unwanted effects are mentioned. Organizations, publications and websites are cited or linked to illustrate issues or as a source of further information. This does not mean that authors, the Editor or IACAPAP endorse their content or recommendations, which should be critically assessed by the reader. -

Somatoform Disorders – September 2017

CrackCast Show Notes – Somatoform Disorders – September 2017 www.canadiem.org/crackcast Chapter 103 – Somatoform disorders Episode overview 1. List 5 somatic symptom and related disorders 2. List 5 common presentations of conversion disorders 3. List 6 ddx of somatic symptom disorder Wisecracks 1. List 6 organic diseases that may be mistaken for somatoform disorders 2. Describe the treatment goals of somatoform disorders Somatoform disorders as a diagnosis has been eliminated from the DSM-5! The patient with functional neurological symptom disorder, what was termed conversion disorder previously, requires a careful and complete neurological examination. Rather than miss the subtle presentation of a neurological disorder, it may be appropriate to perform imaging and obtain neurological and psychiatric consultation. Do not assume that the patient with neurological deficits has a psychiatric disorder. Success with the SSD patient depends on establishing rapport with the patient and legitimizing their complaints to avoid a dysfunctional physician-patient interaction. • Avoid telling the SSD patient “it is all in your head” or “there is nothing wrong with you.” These patients are very sensitive to the idea that their suffering is being dismissed. • A useful approach is to discuss recent stressors with the patient and suggest to them that at times our bodies can be smarter than we are, telling us with physical symptoms that we need assistance. This approach alone may transform the ED visit from a standoff between physician and patient, to a grateful patient who develops greater insight and is amenable to referral. • Avoid prescribing unnecessary or addictive medications to the SSD patient. • If you suspect a diagnosis of SSD, refer the patient to primary care or psychiatry for further evaluation and treatment. -

Psychopathology and Somatic Complaints: a Cross-Sectional Study with Portuguese Adults

healthcare Article Psychopathology and Somatic Complaints: A Cross-Sectional Study with Portuguese Adults Joana Proença Becker 1,*, Rui Paixão 1 and Manuel João Quartilho 2 1 Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences, University of Coimbra, 3000-115 Coimbra, Portugal; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Medicine, University of Coimbra, 3000-548 Coimbra, Portugal; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +351-910741887 Abstract: (1) Background: Functional somatic symptoms (FSS) are physical symptoms that cannot be fully explained by medical diagnosis, injuries, and medication intake. More than the presence of unexplained symptoms, this condition is associated with functional disabilities, psychological distress, increased use of health services, and it has been linked to depressive and anxiety disorders. Recognizing the difficulty of diagnosing individuals with FSS and the impact on public health systems, this study aimed to verify the concomitant incidence of psychopathological symptoms and FSS in Portugal. (2) Methods: For this purpose, 93 psychosomatic outpatients (91.4% women with a mean age of 53.9 years old) and 101 subjects from the general population (74.3% women with 37.8 years old) were evaluated. The survey questionnaire included the 15-item Patient Health Questionnaire, the 20-Item Short Form Survey, the Brief Symptom Inventory, the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale, and questions on sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. (3) Results: Increases in FSS severity were correlated with higher rates of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms. The findings also suggest that increased rates of FSS are associated with lower educational level and Citation: Becker, J.P.; Paixão, R.; female gender. -

Days out of Role and Somatic, Anxious-Depressive, Hypo-Manic, and Psychotic-Like Symptom Dimensions in a Community Sample of Young Adults Jacob J

Crouse et al. Translational Psychiatry (2021) 11:285 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01390-y Translational Psychiatry ARTICLE Open Access Days out of role and somatic, anxious-depressive, hypo-manic, and psychotic-like symptom dimensions in a community sample of young adults Jacob J. Crouse 1, Nicholas Ho 1,JanScott 1,2,3,4, Nicholas G. Martin 5, Baptiste Couvy-Duchesne 5,6,7, Daniel F. Hermens 8,RichardParker 5, Nathan A. Gillespie 9, Sarah E. Medland 5 and Ian B. Hickie 1 Abstract Improving our understanding of the causes of functional impairment in young people is a major global challenge. Here, we investigated the relationships between self-reported days out of role and the total quantity and different patterns of self-reported somatic, anxious-depressive, psychotic-like, and hypomanic symptoms in a community-based cohort of young adults. We examined self-ratings of 23 symptoms ranging across the four dimensions and days out of role in >1900 young adult twins and non-twin siblings participating in the “19Up” wave of the Brisbane Longitudinal Twin Study. Adjusted prevalence ratios (APR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) quantified associations between impairment and different symptom patterns. Three individual symptoms showed significant associations with days out of role, with the largest association for impaired concentration. When impairment was assessed according to each symptom dimension, there was a clear stepwise relationship between the total number of somatic symptoms and the 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; likelihood of impairment, while individuals reporting ≥4 anxious-depressive symptoms or five hypomanic symptoms had greater likelihood of reporting days out of role. -

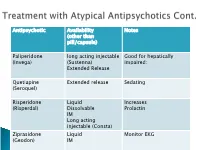

Antipsychotic Availability (Other Than Pill/Capsule) Notes Paliperidone

Antipsychotic Availability Notes (other than pill/capsule) Paliperidone long acting injectable Good for hepatically (Invega) (Sustenna) impaired; Extended Release Quetiapine Extended release Sedating (Seroquel) Risperidone Liquid Increases (Risperdal) Dissolvable Prolactin IM Long acting injectable (Consta) Ziprasidone Liquid Monitor EKG (Geodon) IM Supportive Psychotherapy Club House ACT services NAMI Vocational Rehab Nicotine counseling 1 (or more ) delusions Duration: 1 month or longer Criterion A for Schizophrenia has never been met. Functioning is not markedly impaired Behavior is not obviously odd or bizarre Features: Differential Diagnosis Prevalence: Obsessive-compulsive and ◦ lifetime 0.2 % related disorders ◦ Most frequent is persecutory Delirium • Males > females for Jealous major neurocognitive d/o type psychotic disorder due to • Function is generally better another medical condition than in schizophrenia substance-medication- • Familiar relationship with induced psychotic disorder schizophrenia and Schizophrenia & schizotypal Schizophreniform Depressive and bipolar d/o Schizoaffective Disorder Delusion types Erotomanic Grandiose Jealous Persecutory Somatic Mixed Unspecified • Substance Abuse • Dependence • Withdrawal ◦ Alcohol Divided into 2 ◦ Caffeine groups: ◦ Cannabis ◦ Hallucinogens (with separate ◦ Substance use categories for phencyclidine and other disorders hallucinogens) ◦ Substance-induced ◦ Inhalants disorders ◦ Opioids ◦ Sedatives, hypnotics, and anxiolytics ◦ Stimulants (amphetamine-type -

Olanzapine in Somatic Symptom Disorder

e-Poster number EP.1062 Olanzapine in Somatic Symptom Disorder Chioccioli M*, Crapanzano C*, Politano A*, Beccarini Crescenzi B*, Fagiolini A* * AOUS Siena, Department of Molecular Medicine and Development – Psychiatry Section, Siena, Italy. Introduction: Results: Somatic symptom and related disorders (SSD formerly known as Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test indicates a statistically significant "somatoform disorder" or "somatization disorder") include a (p<0.005) improvement in scores on CGI from T0 (6.14 ± 0.53) group of psychiatric disorders where patients present a wide to T1 (2.00 ± 0.87). Olanzapine average daily dosage per patient range of physical symptoms that are partially or completely was 5.25 mg. Paroxetine was prescribed in 3 patients for consistent with any underlying general medical or neurologic depressive symptoms, with a reduction of olanzapine dose, condition. DSM 5 includes in this category five different owing to the increased blood concentration of olanzapine (up to syndromes: somatic symptom disorder, illness anxiety disorder, 40%) that has been described when this medication is conversion disorder, psychological factors affecting other prescribed in combination with strong inhibitors of CYP2D6 [5]. medical conditions and factitious disorder [1]. Tolerability was good and side effects rated were generally mild Clinical studies and treatment trials for these diseases are (sedation), with no patient that was withdrawn because of it. scarce, with most trials/reports that have focused on antidepressants [2-3]. Other pharmacological -

Hypochondriasis: Considerations for ICD-11 Odile A

Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria. 2014;36:S21–S27 ß 2014 Associac¸a˜ o Brasileira de Psiquiatria doi:10.1590/1516-4446-2013-1218 UPDATE ARTICLE Hypochondriasis: considerations for ICD-11 Odile A. van den Heuvel,1,2 David Veale,3,4 Dan J. Stein5 1Department of Psychiatry, VU University Medical Center (VUmc), Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 2Department of Anatomy & Neurosciences, VUmc, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 3Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London, London, UK. 4Center for Anxiety Disorders and Trauma, South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK. 5Department of Psychiatry, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa. The World Health Organization (WHO) is currently revisiting the ICD. In the 10th version of the ICD, approved in 1990, hypochondriacal symptoms are described in the context of both the primary condition hypochondriacal disorder and as secondary symptoms within a range of other mental disorders. Expansion of the research base since 1990 makes a critical evaluation and revision of both the definition and classification of hypochondriacal disorder timely. This article addresses the considerations reviewed by members of the WHO ICD-11 Working Group on the Classification of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders in their proposal for the description and classification of hypochondriasis. The proposed revision emphasizes the phenomenological overlap with both anxiety disorders (e.g., fear, hypervigilance to bodily symptoms, and avoidance) and obsessive-compulsive and related disorders (e.g., preoccupation and repetitive behaviors) and the distinction from the somatoform disorders (presence of somatic symptom is not a critical characteristic). This revision aims to improve clinical utility by enabling better recognition and treatment of patients with hypochondriasis within the broad range of global health care settings. -

Functional Symptoms Information for Families Functional Symptoms Are Physical Symptoms Without an Obvious Cause

Functional symptoms Information for families Functional symptoms are physical symptoms without an obvious cause. They can also be called Medically Unexplained Symptoms, Somatic Symptom Disorder, Somatoform Disorder or Functional Neurological Disorder. This information sheet from Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) explains about functional symptoms in children and young people and how they can be managed. An Easy Read information sheet is also included within this leaflet. What causes functional symptoms? 3 Can functional symptoms 7 get worse? What sort of issues and stresses 3 can lead to functional symptoms? What can parents do to help? 7 How are functional symptoms 4 Reducing the focus on symptoms 8 diagnosed? Boom and bust 8 What happens next? 4 Will my child always have 9 Why does my child have 5 functional symptoms? functional symptoms? Final words 9 Predisposing factors 5 Further information 9 Precipitating factors 5 and support Perpetuating factors 6 All about symptoms 10 Protective factors 6 with no physical cause Functional symptoms 2 Information for families 20F02324 What sort of issues and Everyone can have physical symptoms such as painful or uncomfortable stresses can lead to feelings inside the body. Usually they functional symptoms? get better on their own, and if they Functional symptoms often occur at times do not, we might ask the doctor of stress. During stressful situations our about them. bodies might react in different ways. Often a reason for them can be found, Some common stressful events may but sometimes it cannot, even after include the doctor has done a range of tests. Starting a new school If the symptoms continue and get in Being bullied the way of everyday life we call these Being stressed at school (for example Functional Symptoms (FS) or Medically exams, friendship difficulties) Unexplained Symptoms (MUS). -

A New Somatic-Type Delusional Disorder Subtype: Delusion Inversus

Volume 25 Number 10| October 2019| Dermatology Online Journal || Commentary 25(10):3 A new somatic-type delusional disorder subtype: delusion inversus Brianna De Souza MD, Amy McMichael MD Affiliations: Department of Dermatology, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA Corresponding Author: Amy McMichael MD, Department of Dermatology, Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center, 1 Medical Center Boulevard, Winston-Salem, NC 27157, Tel: 336-716-7882, Email: [email protected] existence is not only a testament to the complex Abstract interplay between the two disciplines but a reminder The interplay between psychiatric and dermatologic to consider the associated psychiatric or conditions has been recognized for decades as dermatologic sequelae when making a primary evidenced by the widely accepted classification diagnosis. Among the many psychocutaneous system of psychocutaneous disorders: (1) primary disorders seen by dermatologists, one that is not dermatologic disorder with psychiatric sequelae, (2) primary dermatologic disorder exacerbated by stress, often described is the situation in which a patient (3) primary psychiatric disorder with dermatologic presents with a minor, treatable skin disorder that sequelae, and (4) miscellaneous. However, there is the patient perceives as severe or incurable. To our minimal literature regarding dermatologic patients knowledge, there is no mention in the literature of who demonstrate a preoccupation with a more this clinical presentation or an associated diagnosis. severe cutaneous disorder despite evidence In this review, we present a case of one such patient confirming a diagnosis of a minor, treatable skin and propose the need for a new subcategory of condition. These patients are a hybrid of the first and psychocutaneous disorders, named delusion fourth categories and should be classified under a new entity known as delusion inversus. -

Working with DSM 5

Working with DSM 5 Jeff Dunn, MD UNM Center for Rural and Community Behavioral Health Criticisms/Controversies Lack of transparency? (non-disclosure agreements) Low reliability (kappa) in field trials Ties to pharmaceutical industry? (70 % of task force members) “Medicalization” of normal responses or normal individual variation? (dropping of bereavement exclusion from MDD; binge eating d/o; DMDD; mild neurocognitive disorder) Elimination of Multi-axial System “To remove artificial distinctions between medical and mental disorders” Axis IV: a number of psychosocial and environmental conditions can be coded as V Codes Axis V (GAF): replaced by WHO Disability Assessment Schedule and other assessment measures: http://www.psychiatry.org/practice/dsm/dsm5/online- assessment-measures NEURODEVELOPMENTAL DISORDERS Intellectual Disability Intellectual Disability (Intellectual Developmental Disorder) replaces the term Mental Retardation Severity is determined by adaptive functioning rather than cognitive capacity (IQ) Autism Spectrum Disorder Encompasses autism, Asperger’s disorder, childhood disintegrative disorder and pervasive developmental disorder NOS (aside: NOS replaced with other specified disorder or unspecified disorder) Characterized by 1) deficits in social communication and social interaction and 2) restricted repetitive behaviors ADHD For children, onset has been changed from before 7 years of age to before 12 years of age for adults, symptom cutoff is 5 symptoms instead of 6 symptoms Symptoms continue to be drawn from -

Somatization in Primary Care

Michael Kennedy, MFT – Division Director Somatization in Primary Care Michael Kozart, MD, PhD • Setting the Stage • In the most general sense, somatization refers to the presence of medical complaints that appear to be driven by psychological processes more than physical processes. • In a dynamic sense, somatization represents experiential avoidance: turning away from painful thoughts or feelings, and redirecting focus onto physical complaints. • Setting the Stage • PCPs encounter ‘perplexing complaints’ in up to 40% of their patients (McCarron 2006). • There is a huge overlap in symptoms between patients who are primary depressed, anxious, and somatic. • There has been a common misconception that the diagnosis requires somatic symptoms without a known medical cause. In actuality, what matters is not the absence of a medical disorder, but rather the presence of overwhelming and/or disproportionately intense medical complaints—there can be a root medical cause. • Setting the Stage—continued. • Identification is important not only to minimize patient distress, but to prevent exposure to unnecessary and/or dangerous health care interventions. • The DSM 5 Drastically changed the layout for Somatic disorders: • Elimination of antiquated and confusing labels under the heading, Somatiform Disorders: somatization d/o, hypochondriasis, somatic pain disorder, body dysmorphic disorder. Substitution of the simpler, Somatic Symptom Disorder. • Aforementioned emphasis on positive symptoms. • The Categorical View: • DSM 5: Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders • Somatic Symptom Disorder (F45.1) • One or more somatic symptoms that are distressing or result in significant disruption of daily life, usually 6 mnths. • Excessive thoughts, feelings, behaviors related to these symptoms as manifested by: • Preoccupation with medical complaints • Anxiety • Excessive time/energy devoted to medical symptoms • The priority is not the absence of a medical explanation for physical symptoms, but rather the presence of overwhelming physical symptoms—a departure from DSM-IV. -

Chapter 4.Pmd

PSYPSYPSYPSYCHOLOGICALCHOLOGICAL DISORDERSDISORDERS After reading this chapter, you would be able to: understand the basic issues in abnormal behaviour and the criteria used to identify such behaviours, appreciate the factors which cause abnormal behaviour, explain the different models of abnormal behaviour, and describe the major psychological disorders. Introduction Concepts of Abnormality and Psychological Disorders Classification of Psychological Disorders Factors Underlying Abnormal Behaviour Major Psychological Disorders Anxiety Disorders Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders Dissociative Disorders Salient Features of Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders CONTENTS and Dissociative Disorders (Box 4.1) Depressive Disorders Bipolar and Related Disorders Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Key Terms Psychotic Disorders Summary Neurodevelopmental Disorders Review Questions Disruptive, Impulse-Control and Conduct Disorders Project Ideas Feeding and Eating Disorders Weblinks Substance - Related and Addictive Disorders Pedagogical Hints Effects of Alcohol : Some Facts (Box 4.2) Commonly Abused Substances (Box 4.3) 69 Chapter 4 • Psychological Disorders 2021–22 You must have come across people who are unhappy, troubled and dissatisfied. Their minds and hearts are filled with sorrow, unrest and tension and they feel that they are unable to move ahead in their lives; they feel life is a painful, uphill struggle, sometimes not worth living. Famous analytical psychologist Carl Jung has quite remarkably said, “How can I be substantial without casting a shadow? I must have a dark side, too, if I am to be whole and by becoming conscious of my shadow, I remember once more that I am a human being like any other”. At times, some of you Introduction may have felt nervous before an important examination, tense and concerned about your future career or anxious when someone close to you was unwell.