Somatization in Primary Care

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOMATIC SYMPTOM, BODILY DISTRESS and RELATED DISORDERS in CHILDREN and ADOLESCENTS 2019 Edition

IACAPAP Textbook of Child and Adolescent Mental Health Chapter CHILD PSYCHIATRY & PEDIATRICS I.1 SOMATIC SYMPTOM, BODILY DISTRESS AND RELATED DISORDERS IN CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS 2019 edition Olivia Fiertag, Sharon Taylor, Amina Tareen & Elena Garralda Olivia Fiertag MBChB, MRCPsych, PGDip CBT Consultant Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist. Honorary Clinical Researcher, HPFT NHS Trust & collaboration with Imperial College London, UK Conflict of interest: none declared Sharon Taylor BSc, MBBS, MRCP, MRCPsych, CASLAT, PGDip Consultant Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist CNWL Foundation NHS Trust & Honorary Senior Clinical Lecturer Imperial College London, UK. Joint Program Director, St Mary’s Child Sick Girl. Psychiatry Training Scheme Christian Krogh, Conflict of interest: none (1880/1881) National declared Gallery of Norway This publication is intended for professionals training or practicing in mental health and not for the general public. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Editor or IACAPAP. This publication seeks to describe the best treatments and practices based on the scientific evidence available at the time of writing as evaluated by the authors and may change as a result of new research. Readers need to apply this knowledge to patients in accordance with the guidelines and laws of their country of practice. Some medications may not be available in some countries and readers should consult the specific drug information since not all dosages and unwanted effects are mentioned. Organizations, publications and websites are cited or linked to illustrate issues or as a source of further information. This does not mean that authors, the Editor or IACAPAP endorse their content or recommendations, which should be critically assessed by the reader. -

Somatoform Disorders – September 2017

CrackCast Show Notes – Somatoform Disorders – September 2017 www.canadiem.org/crackcast Chapter 103 – Somatoform disorders Episode overview 1. List 5 somatic symptom and related disorders 2. List 5 common presentations of conversion disorders 3. List 6 ddx of somatic symptom disorder Wisecracks 1. List 6 organic diseases that may be mistaken for somatoform disorders 2. Describe the treatment goals of somatoform disorders Somatoform disorders as a diagnosis has been eliminated from the DSM-5! The patient with functional neurological symptom disorder, what was termed conversion disorder previously, requires a careful and complete neurological examination. Rather than miss the subtle presentation of a neurological disorder, it may be appropriate to perform imaging and obtain neurological and psychiatric consultation. Do not assume that the patient with neurological deficits has a psychiatric disorder. Success with the SSD patient depends on establishing rapport with the patient and legitimizing their complaints to avoid a dysfunctional physician-patient interaction. • Avoid telling the SSD patient “it is all in your head” or “there is nothing wrong with you.” These patients are very sensitive to the idea that their suffering is being dismissed. • A useful approach is to discuss recent stressors with the patient and suggest to them that at times our bodies can be smarter than we are, telling us with physical symptoms that we need assistance. This approach alone may transform the ED visit from a standoff between physician and patient, to a grateful patient who develops greater insight and is amenable to referral. • Avoid prescribing unnecessary or addictive medications to the SSD patient. • If you suspect a diagnosis of SSD, refer the patient to primary care or psychiatry for further evaluation and treatment. -

Psychopathology and Somatic Complaints: a Cross-Sectional Study with Portuguese Adults

healthcare Article Psychopathology and Somatic Complaints: A Cross-Sectional Study with Portuguese Adults Joana Proença Becker 1,*, Rui Paixão 1 and Manuel João Quartilho 2 1 Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences, University of Coimbra, 3000-115 Coimbra, Portugal; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Medicine, University of Coimbra, 3000-548 Coimbra, Portugal; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +351-910741887 Abstract: (1) Background: Functional somatic symptoms (FSS) are physical symptoms that cannot be fully explained by medical diagnosis, injuries, and medication intake. More than the presence of unexplained symptoms, this condition is associated with functional disabilities, psychological distress, increased use of health services, and it has been linked to depressive and anxiety disorders. Recognizing the difficulty of diagnosing individuals with FSS and the impact on public health systems, this study aimed to verify the concomitant incidence of psychopathological symptoms and FSS in Portugal. (2) Methods: For this purpose, 93 psychosomatic outpatients (91.4% women with a mean age of 53.9 years old) and 101 subjects from the general population (74.3% women with 37.8 years old) were evaluated. The survey questionnaire included the 15-item Patient Health Questionnaire, the 20-Item Short Form Survey, the Brief Symptom Inventory, the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale, and questions on sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. (3) Results: Increases in FSS severity were correlated with higher rates of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms. The findings also suggest that increased rates of FSS are associated with lower educational level and Citation: Becker, J.P.; Paixão, R.; female gender. -

Treating Somatization

TREATING SOMATIZATION TREATING SOMATIZATION A Cognitive-Behavioral Approach Robert L. Woolfolk Lesley A. Allen THE GUILFORD PRESS New York London © 2007 The Guilford Press A Division of Guilford Publications, Inc. 72 Spring Street, New York, NY 10012 www.guilford.com All rights reserved Except as indicated, no part of this book may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the Publisher. Printed in the United States of America This book is printed on acid-free paper. Last digit is print number:987654321 LIMITED PHOTOCOPY LICENSE These materials are intended for use only by qualified mental health profes- sionals. The Publisher grants to individual purchasers of this book nonassignable permission to reproduce all materials for which photocopying permission is specifically granted in a footnote. This license is limited to you, the individ- ual purchaser, for use with your own clients and patients. It does not extend to additional clinicians or practice settings, nor does purchase by an institu- tion constitute a site license. This license does not grant the right to reproduce these materials for resale, redistribution, or any other purposes (including but not limited to books, pamphlets, articles, video- or audiotapes, and hand- outs or slides for lectures or workshops). Permission to reproduce these materials for these and any other purposes must be obtained in writing from the Permissions Department of Guilford Publications. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Woolfolk, Robert L. Treating somatization : a cognitive-behavioral approach / by Robert L. -

Investigating Correlations Between Defence Mechanisms and Pathological Personality Characteristics

rev colomb psiquiat. 2019;48(4):232–243 www.elsevier.es/rcp Artículo original Investigating Correlations Between Defence Mechanisms and Pathological Personality Characteristics Lucas de Francisco Carvalho ∗, Ana Maria Reis, Giselle Pianowski Department of Psicology, Universidade São Francisco, Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil article info abstract Article history: Introduction: The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between defence Received 4 October 2017 mechanisms and pathological personality traits. Accepted 10 January 2018 Material and methods: We analysed 320 participants aged from 18 to 64 years (70.6% women, Available online 10 February 2018 87.5% university students) who completed the Dimensional Clinical Personality Inventory (IDCP) and the Defence Style Questionnaire (DSQ-40). We conducted comparisons and cor- Keywords: relations and a regression analysis. Personality disorders Results: The results showed expressive differences (d>1.0) between mature, neurotic and Defence mechanisms immature defence mechanism groups, and it was observed that pathological personality Self-assessment traits are more typical in people who use less mature defence mechanisms (i.e., neurotic and immature), which comprises marked personality profiles for each group, according to the IDCP. We also found correlations between some of the 40 specific mechanisms of the DSQ-40 and the 12 dimensions of pathological personality traits from the IDCP (r ≥ 0.30 to r ≤ 0.43), partially supported by the literature. In addition, we used regression analysis to verify the potential of the IDCP dimension clusters (related to personality disorders) to predict defence mechanisms, revealing some minimally expressive predictive values (between 20% and 35%). Discussion: The results indicate that those who tend to use immature defence mechanisms are also those most likely to present pathological personality traits. -

Days out of Role and Somatic, Anxious-Depressive, Hypo-Manic, and Psychotic-Like Symptom Dimensions in a Community Sample of Young Adults Jacob J

Crouse et al. Translational Psychiatry (2021) 11:285 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01390-y Translational Psychiatry ARTICLE Open Access Days out of role and somatic, anxious-depressive, hypo-manic, and psychotic-like symptom dimensions in a community sample of young adults Jacob J. Crouse 1, Nicholas Ho 1,JanScott 1,2,3,4, Nicholas G. Martin 5, Baptiste Couvy-Duchesne 5,6,7, Daniel F. Hermens 8,RichardParker 5, Nathan A. Gillespie 9, Sarah E. Medland 5 and Ian B. Hickie 1 Abstract Improving our understanding of the causes of functional impairment in young people is a major global challenge. Here, we investigated the relationships between self-reported days out of role and the total quantity and different patterns of self-reported somatic, anxious-depressive, psychotic-like, and hypomanic symptoms in a community-based cohort of young adults. We examined self-ratings of 23 symptoms ranging across the four dimensions and days out of role in >1900 young adult twins and non-twin siblings participating in the “19Up” wave of the Brisbane Longitudinal Twin Study. Adjusted prevalence ratios (APR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) quantified associations between impairment and different symptom patterns. Three individual symptoms showed significant associations with days out of role, with the largest association for impaired concentration. When impairment was assessed according to each symptom dimension, there was a clear stepwise relationship between the total number of somatic symptoms and the 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; likelihood of impairment, while individuals reporting ≥4 anxious-depressive symptoms or five hypomanic symptoms had greater likelihood of reporting days out of role. -

Defense Mechanisms.Pdf

Defense Mechanisms According to Sigmund Freud, who originated the Defense Mechanism theory, Defense Mechanisms occur when our ego cannot meet the demands of reality. They are psychological strategies brought into play by the unconscious mind to manipulate, deny or distort reality so as to maintain a socially acceptable self-image. Healthy people normally use these mechanisms throughout life. it becomes pathological only when its persistent use leads to maladaptive behavior such that the physical and/or mental health of the individual is adversely affected. The purpose of ego defense mechanisms is to protect the mind/self/ego from anxiety and/or social sanctions and/or to provide a refuge from a situation with which one cannot currently cope. Defense mechanisms are unconscious coping mechanisms that reduce anxiety generated by threats from unacceptable impulses In 1977, psychologist George Vaillant took Freud’s theory and built upon it by categorizing them, placing Freud’s mechanisms on a continuum related to their psychoanalytical developmental level. Level 1: Pathological Defenses The mechanisms on this level, when predominating, almost always are severely pathological. These six defense’s, in conjunction, permit one to effectively rearrange external experiences to eliminate the need to cope with reality. The pathological users of these mechanisms frequently appear irrational or insane to others. These are the "psychotic" defense’s, common in overt psychosis. However, they are found in dreams and throughout childhood as well. They include: Delusional Projection: Delusions about external reality, usually of a persecutory nature. Conversion: the expression of an intra-psychic conflict as a physical symptom; some examples include blindness, deafness, paralysis, or numbness. -

Hypochondriasis and Somatization Disorder

Ch14.qxd 28/6/07 1:36 PM Page 152 14 Hypochondriasis and Somatization Disorder Don R. Lipsitt CONTENTS 14.1 The Concept of Somatization . 153 14.2 Classification . 154 14.2.1 From DSM-I to DSM-III . 154 14.2.2 Case History (Part 1). 155 14.3 Diagnosis . 156 14.3.1 Hypochondriasis . 156 14.3.2 Somatization Disorder . 160 14.3.3 Case History (Part 2). 163 14.4 The Consultation-Liaison Psychiatrist’s Role in Somatization . 163 14.5 Conclusion . 164 On a busy day in a general physician’s office, perhaps 50% or more of the patients with physical complaints will have no definitive explanation for their ailment (Kroenke and Mangelsdorff, 1989). The patients present with distress from fatigue, chest pain, cough, back pain, shortness of breath, and a host of other painful or worrisome bodily concerns. For most, the physician’s expressing interest, taking a thorough history, doing a physical examination, and offering reassurance, a mod- est intervention, or a pharmacologic prescription suffices to assuage the patient’s pain, anxiety, and physical distress. But for some, these simple measures fall short of their expected result, marking the beginning of what may become a chronic search for relief, including frequent anxiety-filled visits to more than one physician, and in extreme cases even multiple hospitalizations and possibly surgery. The longer and more persistently this pattern appears, the more likely it will generate referrals to specialists for expert consultation, greater frustration in both the primary physician and the patient, and ultimately dysfunctional patient–physician relationships with inappropriate labeling of the patient as a “problem” or “difficult” patient, and perhaps even worse (Lipsitt, 1970). -

O-P 28 Fares Srouji

psychological factors in noncompliance among hemodialysis patients Srouji Fares Department of Nephrology, The Nazareth Hospital EMMS, Nazareth, Israel Noncompliance among HD patients • None-adherence is universally recognized as one of the major clinical issues in the management of ESRD among Hemodialysis patient. None Adherence Country Fluid Nutrition Medication ↓ intake Germany & U.S.A 72.3% 80.4% (N=456)1 Iran (N=237)2 45.2% 41.1% Turkey (N=154)3 95% 98.3% Italy (N=1238)4 52% India (N=150)5 37% The psychological impact of HD • Hemodialysis heavily violates the bio-psychosocial balance of the patient. • HD patient tend to use neurotic and immature defense mechanisms (i.e. reversal reaction, denial, dissociation, projection, somatization and Splitting)6-8 • Anxiety & Depression are the most common psychological issues among HD patient9 + Change in body image10,11 Low self-esteem12,13 10,14-15 + Dependence on the machine & clinical team Loss Hopelessness10,16 + Numerous restrictions 17-19 + Anxiety & Depression Ineffective psychological6-8 Defense/coping mechanisms Noncompliance20,21 Vaillant’s Levels of Defense Immature defenses Passive aggression, Acting out, Dissociation, Projection Autistic fantasy: Devaluation, Idealization, Splitting Neurotic (intermediate) defenses Intellectualization, Isolation, Repression, Reaction formation, Displacement, Somatization, Undoing, Rationalization Mature defenses Suppression, Altruism, Humor, Sublimation 4 The psychological impact of HD • Hemodialysis heavily violates the bio-psychosocial balance -

Antipsychotic Availability (Other Than Pill/Capsule) Notes Paliperidone

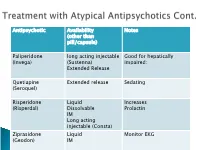

Antipsychotic Availability Notes (other than pill/capsule) Paliperidone long acting injectable Good for hepatically (Invega) (Sustenna) impaired; Extended Release Quetiapine Extended release Sedating (Seroquel) Risperidone Liquid Increases (Risperdal) Dissolvable Prolactin IM Long acting injectable (Consta) Ziprasidone Liquid Monitor EKG (Geodon) IM Supportive Psychotherapy Club House ACT services NAMI Vocational Rehab Nicotine counseling 1 (or more ) delusions Duration: 1 month or longer Criterion A for Schizophrenia has never been met. Functioning is not markedly impaired Behavior is not obviously odd or bizarre Features: Differential Diagnosis Prevalence: Obsessive-compulsive and ◦ lifetime 0.2 % related disorders ◦ Most frequent is persecutory Delirium • Males > females for Jealous major neurocognitive d/o type psychotic disorder due to • Function is generally better another medical condition than in schizophrenia substance-medication- • Familiar relationship with induced psychotic disorder schizophrenia and Schizophrenia & schizotypal Schizophreniform Depressive and bipolar d/o Schizoaffective Disorder Delusion types Erotomanic Grandiose Jealous Persecutory Somatic Mixed Unspecified • Substance Abuse • Dependence • Withdrawal ◦ Alcohol Divided into 2 ◦ Caffeine groups: ◦ Cannabis ◦ Hallucinogens (with separate ◦ Substance use categories for phencyclidine and other disorders hallucinogens) ◦ Substance-induced ◦ Inhalants disorders ◦ Opioids ◦ Sedatives, hypnotics, and anxiolytics ◦ Stimulants (amphetamine-type -

Psychopathic Personality Traits and Somatization: Sex Differences and the Mediating Role of Negative Emotionality

P1: MRM/SPH P2: MRM/RKP QC: MRM Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment (JOBA) PP099-298982-03 March 13, 2001 10:23 Style file version Nov. 07, 2000 Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, Vol. 23, No. 1, 2001 Psychopathic Personality Traits and Somatization: Sex Differences and the Mediating Role of Negative Emotionality Scott O. Lilienfeld1,2 and Tanya H. Hess1 Although a number of investigations have provided evidence for an association between antisocial per- sonality disorder and somatization disorder, the variables underlying this association remain unknown. We examined the relations among measures of primary and secondary psychopathy, somatization, and negative emotionality (NE) in 150 undergraduates. Somatization was positively and significantly cor- related with measures of secondary, but not primary, psychopathy, and the relations between secondary psychopathy indices and somatization tended to be significantly stronger in females than in males. Some support was found for the hypothesis that the association between secondary psychopathy and somatization is mediated by NE, but not for the hypothesis that low levels of behavioral inhibition lead to somatization. Although the present findings are consistent with the possibility that somatization is a sex-differentiated manifestation of secondary psychopathic traits, replication of these findings in clinical samples will be necessary. KEY WORDS: psychopathy; antisocial personality disorder; somatization disorder; sex differences; negative emotionality. The phenomenon of “comorbidity,” or diagnostic mer syndrome is characterized by a chronic history of covariation, represents one of the foremost challenges antisocial and criminal behavior, whereas the latter is to contemporary psychopathology researchers (Caron & characterized by a chronic history of unexplained physi- Rutter, 1991; Frances et al., 1992). -

Symptomatology and Comorbidity of Somatization Disorder Amongst General Outpatients Attending a Family Medicine Clinic in South West Nigeria

Ann Ibd. Pg. Med 2014. Vol.12, No.2 96-102 SYMPTOMATOLOGY AND COMORBIDITY OF SOMATIZATION DISORDER AMONGST GENERAL OUTPATIENTS ATTENDING A FAMILY MEDICINE CLINIC IN SOUTH WEST NIGERIA. A.M. Obimakinde1, M.M. Ladipo2 and A.E. Irabor3 1. General Outpatients Department, Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, Ekiti State, Nigeria. 2. General Outpatients Department, University College Hospital, Ibadan. 3. Family Physician Department, University College Hospital, Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria. Correspondence: ABSTRACT Dr. Abimbola M. Obimakinde Background: Individuals with somatization may be the most difficult to Family Medicine Department. manage because of the diverse and frequent complaints across many organ Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, systems. They often use impressionistic language to describe circumstantial Ekiti State. symptoms which though bizarre, may resemble genuine diseases. The E-mail: [email protected]. disorder is best understood in the context “illness” behaviour, masking Phone No.: 08028406568. underlying mental disorder, manifesting solely as somatic symptoms or with comorbidity. Objective: To evaluate somatization symptoms and explore its comorbidity in order to improve the management of these patients. Methods: A cross-sectional survey of 60 somatizing patients who were part of a case-control study, selected by consecutive sampling of 2668 patients who presented at the Family Medicine Clinic of University College Hospital Ibadan, Nigeria between May-August 2009. Data was collected using the ICPC-2, WHO- Screener and Diagnostic Schedule and analysed with SPSS 16. Results: There were at least 5 symptoms of somatization in 93.3% of the patients who were mostly females. Majority had crawling sensation, “headache”, unexplained limb ache, pounding heart, lump in the throat and insomnia.