Groundwater Irrigation and Its Implications for Water Policy in Semiarid Countries: the Spanish Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluating Vapor Intrusion Pathways

Evaluating Vapor Intrusion Pathways Guidance for ATSDR’s Division of Community Health Investigations October 31, 2016 Contents Acronym List ........................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................... 2 What are the potential health risks from the vapor intrusion pathway? ............................................................................... 2 When should a vapor intrusion pathway be evaluated? ........................................................................................................ 3 Why is it so difficult to assess the public health hazard posed by the vapor intrusion pathway? .......................................... 3 What is the best approach for a public health evaluation of the vapor intrusion pathway? ................................................. 5 Public health evaluation.......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Vapor intrusion evaluation process outline ............................................................................................................................ 8 References… …...................................................................................................................................................................... -

Sediment Transport Model for a Surface Irrigation System

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Applied and Environmental Soil Science Volume 2013, Article ID 957956, 10 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/957956 Research Article Sediment Transport Model for a Surface Irrigation System Damodhara R. Mailapalli,1 Narendra S. Raghuwanshi,2 and Rajendra Singh2 1 BiologicalSystemsEngineering,UniversityofWisconsin,Madison,WI53706,USA 2 Agricultural and Food Engineering Department, Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur 721302, India Correspondence should be addressed to Damodhara R. Mailapalli; [email protected] Received 16 March 2013; Revised 25 June 2013; Accepted 11 July 2013 Academic Editor: Keith Smettem Copyright © 2013 Damodhara R. Mailapalli et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Controlling irrigation-induced soil erosion is one of the important issues of irrigation management and surface water impairment. Irrigation models are useful in managing the irrigation and the associated ill effects on agricultural environment. In this paper, a physically based surface irrigation model was developed to predict sediment transport in irrigated furrows by integrating an irrigation hydraulic model with a quasi-steady state sediment transport model to predict sediment load in furrow irrigation. The irrigation hydraulic model simulates flow in a furrow irrigation system using the analytically solved zero-inertial overland flow equations and 1D-Green-Ampt, 2D-Fok, and Kostiakov-Lewis infiltration equations. Performance of the sediment transport model wasevaluatedforbareandcroppedfurrowfields.Theresultsindicated that the sediment transport model can predict the initial sediment rate adequately, but the simulated sediment rate was less accurate for the later part of the irrigation event. -

Subsurface Drip Irrigation (Sdi) Systems

NETAFIM USA SUBSURFACE DRIP IRRIGATION (SDI) SYSTEMS ADVANCED DRIP/MICRO IRRIGATION TECHNOLOGIES SUBSURFACE DRIP IRRIGATION QUALITY AND DEPENDABILITY FROM THE LEADERS IN DRIP IRRIGATION For over 50 years, growers world-wide have counted on Netafim for the most reliable, cost-effective and efficient ways to deliver water, nutrients and chemicals to their crops. This tradition continues with subsurface drip irrigation (SDI), the most advanced method for irrigating agricultural crops. With proper management of water and nutrients, a subsurface drip irrigation system can deliver maximum yields and optimal water use efficiencies. Drip irrigation, whether surface or subsurface, often results in increased production and yields as well as increased quality and uniformity. It provides more efficient use of the applied water resulting in substantial water savings. The flexibility of drip irrigation increases a grower’s ability to farm marginal land. WHAT IS SUBSURFACE DRIP IRRIGATION (SDI)? Subsurface drip irrigation is a variation on traditional drip irrigation where the dripline (tubing and drippers) is buried beneath the soil surface, rather than laid on the ground, supplying water directly to the roots. The depth and distance the dripline is placed depends on the soil type and the plant’s root structure. SDI is more than an irrigation system, it is a root zone management tool. Fertilizer can be applied to the root zone in a quantity when it will be most beneficial - resulting in greater use efficiencies and better crop performance. SUBSURFACE DRIP IRRIGATION (SDI) ADVANTAGES The key benefit of a surface micro-irrigation system is to apply low volumes of water and nutrients uniformly to every plant across the entire field. -

Groundwater Overdraft, Electricity, and Wrong Incentives : Evidence from Mexico

Groundwater Overdraft, Electricity, and Wrong Incentives : Evidence from Mexico Vincente Ruiz WP 2016.05 Suggested citation: V. Ruiz (2016). Groundwater Overdraft, Electricity, and Wrong Incentives : Evidence from Mexico. FAERE Working Paper, 2016.05. ISSN number: 2274-5556 www.faere.fr Groundwater Overdraft, Electricity, and Wrong Incentives: Evidence from Mexico by Vicente Ruiz⇤ Last version: January 2016 Abstract Groundwater overdraft is threatening the sustainability of an increasing number of aquifers in Mexico. The excessive amount of groundwater ex- tracted by irrigation farming has significantly contributed to this problem. The objective of this paper is to analyse the effect of changes in ground- water price over the allocation of different production inputs. I model the technology of producers facing groundwater overdraft through a Translog cost function and using a combination of multiple micro-data sources. My results show that groundwater demand is inelastic, -0.54. Moreover, these results also show that both labour and fertiliser can act as substitutes for groundwater, further reacting to changes in groundwater price. JEL codes:Q12,Q25 Key words: Groundwater, Electricity, Subsidies, Mexico, Translog Cost ⇤Université Paris 1 - Panthéon Sorbonne, Paris School of Economics (PSE). Centre d’Économie de la Sorbonne, 106-112 Boulevard de l’Hopital, 75647, Paris Cedex 13, France. Email: [email protected] Introduction The high rate of groundwater extraction in Mexico is threatening the sustainability of an increasing number of aquifers in the country. Today in Mexico 1 out of 6aquifersisconsideredtobeoverexploited(CONAGUA, 2010). Groundwater overdraft is not only an important cause of major environmental problems, but it also has a direct impact on economic activities and the wellbeing of a high share of the population. -

Reference: Groundwater Quality and Groundwater Pollution

PUBLICATION 8084 FWQP REFERENCE SHEET 11.2 Reference: Groundwater Quality and Groundwater Pollution THOMAS HARTER is UC Cooperative Extension Hydrogeology Specialist, University of California, Davis, and Kearney Agricultural Center. roundwater quality comprises the physical, chemical, and biological qualities of UNIVERSITY OF G ground water. Temperature, turbidity, color, taste, and odor make up the list of physi- CALIFORNIA cal water quality parameters. Since most ground water is colorless, odorless, and Division of Agriculture without specific taste, we are typically most concerned with its chemical and biologi- and Natural Resources cal qualities. Although spring water or groundwater products are often sold as “pure,” http://anrcatalog.ucdavis.edu their water quality is different from that of pure water. In partnership with Naturally, ground water contains mineral ions. These ions slowly dissolve from soil particles, sediments, and rocks as the water travels along mineral surfaces in the pores or fractures of the unsaturated zone and the aquifer. They are referred to as dis- solved solids. Some dissolved solids may have originated in the precipitation water or river water that recharges the aquifer. A list of the dissolved solids in any water is long, but it can be divided into three groups: major constituents, minor constituents, and trace elements (Table 1). The http://www.nrcs.usda.gov total mass of dissolved constituents is referred to as the total dissolved solids (TDS) concentration. In water, all of the dissolved solids are either positively charged ions Farm Water (cations) or negatively charged ions (anions). The total negative charge of the anions always equals the total positive charge of the cations. -

4. Drainage of Irrigated Lands

ARBA MINCH UNIVERSITY Water Technology Institute Faculty of Meteorology and Hydrology Course Name:-Irrigated Lands Hydrology Course Code:- MHH1403 CHAPTER FOUR DRAINAGE OF IRRIGATED LANDS Prepared by: Tegegn T.(MSc.) Hydrology Objectives of the chapter • By the end of the session, the student will able to: – Understand what we mean by Agricultural drainage – Understand causes of excess water in agricultural lands – Know Problems and effects of poor drainage – Understand need of drainage – Know different types of drainage 4/21/2020 2 4.1 Definition of Drainage • Good water management of an irrigation scheme not only requires proper water application but also a proper drainage system. • Agricultural drainage can be defined as the removal of excess surface water and/or the lowering of the groundwater table below the root zone in order to improve plant growth. 4/21/2020 3 Cont… Class activity • Be in group and discuss on following topics – Causes of excess water or rise of water table – What are the effects of poor drainage – Why drainage is needed? 4/21/2020 4 Causes of excess water or rise of WT: • Natural Causes: – Poor natural drainage of the subsoil – Submergence under floods – Deep percolation from rainfall – Drainage water coming from adjacent areas. • Artificial Causes: – High intensity of irrigated agriculture irrespective of the soil or subsoil – Heavy seepage losses from unlined canals – Enclosing irrigated fields with embankments – Non-maintenance of natural drainages or blocking of natural drainages channels by roads. – the extra water applied for the flushing away of 4/21/2020 salts from the root zone. 5 4.2 Problems and effects of poor drainage • Drainage problem could be: – Surface drainage problem ---- when excess water builds up the water table and reaches to the ground level (i.e. -

Surface Water and Groundwater Interactions in Traditionally Irrigated Fields in Northern New Mexico, U.S.A

water Article Surface Water and Groundwater Interactions in Traditionally Irrigated Fields in Northern New Mexico, U.S.A. Karina Y. Gutiérrez-Jurado 1, Alexander G. Fernald 2, Steven J. Guldan 3 and Carlos G. Ochoa 4,* 1 School of the Environment, Flinders University, Bedford Park, SA 5042, Australia; karina.gutierrez@flinders.edu.au 2 Water Resources Research Institute, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM 88003, USA; [email protected] 3 Sustainable Agriculture Science Center, New Mexico State University, Alcalde, NM 87511, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Animal and Rangeland Sciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-541-737-0933 Academic Editor: Ashok K. Chapagain Received: 18 December 2016; Accepted: 3 February 2017; Published: 10 February 2017 Abstract: Better understanding of surface water (SW) and groundwater (GW) interactions and water balances has become indispensable for water management decisions. This study sought to characterize SW-GW interactions in three crop fields located in three different irrigated valleys in northern New Mexico by (1) estimating deep percolation (DP) below the root zone in flood-irrigated crop fields; and (2) characterizing shallow aquifer response to inputs from DP associated with irrigation. Detailed measurements of irrigation water application, soil water content fluctuations, crop field runoff, and weather data were used in the water budget calculations for each field. Shallow wells were used to monitor groundwater level response to DP inputs. The amount of DP was positively and significantly related to the total amount of irrigation water applied for the Rio Hondo and Alcalde sites, but not for the El Rito site. -

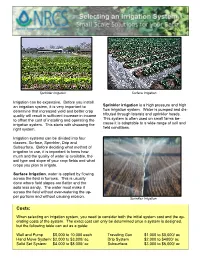

Selecting an Irrigation System, You Need to Consider Both the Initial System Cost and the Op- Erating Costs of the System

Sprinkler Irrigation Surface Irrigation Irrigation can be expensive. Before you install an irrigation system, it is very important to Sprinkler irrigation is a high pressure and high determine that increased yield and better crop flow irrigation system. Water is pumped and dis- quality will result in sufficient increase in income tributed through laterals and sprinkler heads. to offset the cost of installing and operating the This system is often used on small farms be- irrigation system. This starts with choosing the cause it is adaptable to a wide range of soil and right system. field conditions. Irrigation systems can be divided into four classes: Surface, Sprinkler, Drip and Subsurface. Before deciding what method of irrigation to use, it is important to know how much and the quality of water is available, the soil type and slope of your crop fields and what crops you plan to irrigate. Surface Irrigation, water is applied by flowing across the field in furrows. This is usually done where field slopes are flatter and the soils less sandy. The water must make it across the field without over-watering the up- per portions and without causing erosion. Sprinkler Irrigation Costs: When selecting an irrigation system, you need to consider both the initial system cost and the op- erating costs of the system. The exact cost can only be determined once a system is designed, but the following table can act as a guide: Well and Pump $5,000 to 10,000 each Traveling Gun $1,000 to $8,000/ ac Hand Move System: $2,000 to $3,000/ ac Drip System $2,000 to $4000/ ac Solid Set System: $4,000 to $8,000/ ac Subsurface $3,000 to $6,000/ ac Selecting an Irrigation System Selecting a System. -

Dissertation Simulating the Fate And

DISSERTATION SIMULATING THE FATE AND TRANSPORT OF SALINITY SPECIES IN A SEMI- ARID AGRICULTURAL GROUNDWATER SYSTEM: MODEL DEVELOPMENT AND APPLICATION Submitted by Saman Tavakoli Kivi Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 2018 Doctoral Committee: Advisor: Ryan T. Bailey Co-Advisor: Timothy K. Gates Michael J. Ronayne Aditi Bhaskar Copyright by Saman Tavakoli Kivi 2018 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT SIMULATING THE FATE AND TRANSPORT OF SALINITY SPECIES IN A SEMI- ARID AGRICULTURAL GROUNDWATER SYSTEM: MODEL DEVELOPMENT AND APPLICATION Many irrigated agricultural areas worldwide suffer from salinization of soil, groundwater, and nearby river systems. Increased salinity concentrations, which can lead to decreased crop yield, are due principally to the presence of salt minerals and high rates of evapotranspiration. High groundwater salt loading to nearby river systems also affects downstream areas when saline river water is diverted for additional uses. Irrigation-induced salinity is the principal water quality problem in the semi-arid region of the western United States due to the extensive background quantities of salt in rocks and soils. Due to the importance of the problem and the complex hydro-chemical processes involved in salinity fate and transport, a physically-based spatially-distributed numerical model is needed to assess soil and groundwater salinity at the regional scale. Although several salinity transport models have been developed in recent decades, these models focus on salt species at the small scale (i.e. soil profile or field), and no attempts thus far have been made at simulating the fate, storage, and transport of individual interacting salt ions at the regional scale within a river basin. -

Effects of Irrigation Performance on Water Balance: Krueng Baro Irri- Gation Scheme (Aceh-Indonesia) As a Case Study

DOI: 10.2478/jwld-2019-0040 © Polish Academy of Sciences (PAN), Committee on Agronomic Sciences JOURNAL OF WATER AND LAND DEVELOPMENT Section of Land Reclamation and Environmental Engineering in Agriculture, 2019 2019, No. 42 (VII–IX): 12–20 © Institute of Technology and Life Sciences (ITP), 2019 PL ISSN 1429–7426, e-ISSN 2083-4535 Available (PDF): http://www.itp.edu.pl/wydawnictwo/journal; http://www.degruyter.com/view/j/jwld; http://journals.pan.pl/jwld Received 07.12.2018 Reviewed 05.03.2019 Accepted 07.03.2019 Effects of irrigation performance on water balance: A – study design B – data collection Krueng Baro Irrigation Scheme (Aceh-Indonesia) C – statistical analysis D – data interpretation E – manuscript preparation as a case study F – literature search Azmeri AZMERI1) ABCDEF , Alfiansyah YULIANUR2) AD, Uli ZAHRATI3) BC, Imam FAUDLI4) BC 1) orcid.org/0000-0002-3552-036X; Universitas Syiah Kuala, Faculty of Engineering, Civil Engineering Department Jl. Tgk. Syeh Abdul Rauf No. 7, Darussalam – Banda Aceh 23111, Indonesia; e-mail: [email protected] 2) orcid.org/0000-0002-8679-1792; Universitas Syiah Kuala, Faculty of Engineering, Civil Engineering Department, Banda Aceh, Indonesia; e-mail: [email protected] 3) orcid.org/0000-0001-8665-8193; Office of River Region of Sumatra-I, Lueng Bata, Banda Aceh, Indonesia; e-mail: [email protected] 4) orcid.org/0000-0002-4944-3449; Hydrology and hydraulics consultant; e-mail: [email protected] For citation: Azmeri A., Yulianur A., Zahrati U., Faudli I. 2019. Effects of irrigation performance on water balance: Krueng Baro Irri- gation Scheme (Aceh-Indonesia) as a case study. -

7. Design and Evaluation of Surface Irrigation Methods in Southern Gujarat Using Surdev (Gau)

Joint Completion Report on IDNP Redt# 3 "Computer Modeling in Irrigation and Drainage" 7. DESIGN AND EVALUATION OF SURFACE IRRIGATION METHODS IN SOUTHERN GUJARAT USING SURDEV (GAU) 7.1 Introduction The study area is located in the central western coast of India in the Southern Gujarat. South Gujarat comprises of the Valsad, the Navsari, the Dang, the Surat and the Bharuch districts with rainfall varying from about 850 mm to 2000 mm. The general topography of the area is flat. The soils of the area are clayey while some parts also have clay loamsoils. The main crops of the South Gujarat are sugarcane, paddy and fruit crops. Paddy is taken both during khavifand summer seasons. Sugarcane crop occupies more than 50% of the culturable command area in South Gujarat and it is mostly irrigated with furrow method of irrigation. Furrow method of irrigation is also adopted for many other vegetable crops of this area. Paddy and fruit crops like banana, mango, and papaya are irrigated using basin irrigation method. In fruit crops, ring basin method of irrigation is adopted. In paddy, farmers adopt field to field irrigation. The area, in addition to heavy rainfall, receives canal water throughout the year. The region has many streams flowing from eastern side and draining into the Arabian Sea. Farmers of the region, due to easy availability of water, knowingly or unknowingly apply more water, especially in the upper reaches of the canal. On the other hand, in mid and tail reaches of canal command and in well-irrigated areas, the water application is less than the demand and is non-uniform. -

Freshwater Resources

3 Freshwater Resources Coordinating Lead Authors: Blanca E. Jiménez Cisneros (Mexico), Taikan Oki (Japan) Lead Authors: Nigel W. Arnell (UK), Gerardo Benito (Spain), J. Graham Cogley (Canada), Petra Döll (Germany), Tong Jiang (China), Shadrack S. Mwakalila (Tanzania) Contributing Authors: Thomas Fischer (Germany), Dieter Gerten (Germany), Regine Hock (Canada), Shinjiro Kanae (Japan), Xixi Lu (Singapore), Luis José Mata (Venezuela), Claudia Pahl-Wostl (Germany), Kenneth M. Strzepek (USA), Buda Su (China), B. van den Hurk (Netherlands) Review Editor: Zbigniew Kundzewicz (Poland) Volunteer Chapter Scientist: Asako Nishijima (Japan) This chapter should be cited as: Jiménez Cisneros , B.E., T. Oki, N.W. Arnell, G. Benito, J.G. Cogley, P. Döll, T. Jiang, and S.S. Mwakalila, 2014: Freshwater resources. In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Field, C.B., V.R. Barros, D.J. Dokken, K.J. Mach, M.D. Mastrandrea, T.E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K.L. Ebi, Y.O. Estrada, R.C. Genova, B. Girma, E.S. Kissel, A.N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P.R. Mastrandrea, and L.L. White (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 229-269. 229 Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................................ 232 3.1. Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................................