Active Cognition in Bartending

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Decade Ahead

Issue 03 1 Positivity wins The Decade Ahead It's official: basic Stewards of classic Linking up with kindred Ponies got talent! bubbles are back! cocktails for the spirits beyond the Celebrating diversity generations to come industry in our team 2020 A Jigger & Pony Publication $18.00 + GST 56 2 3 Gin & Sonic Monkey 47 Gin, soda water, tonic water, grapefruit juice 25 per cocktail Prices subject to 10% service charge and 7% GST 4 5 Contents pg. Basic bubbles are back 10 Stripped down cocktails that are deceptively simple Principal Footloose and fancy fizz 16 Celebrating humankind’s fascination with things that go ‘pop’ bartender’s A sense of place 20 Embracing flavours that evoke welcome a sense of place across Asia Kindred spirits 22 Meet team Fossa, local craft chocolate makers with a passion Positivity wins! for creating new flavours Collaboration across borders 26 My bartending journey started eight years ago, around the same time that Jigger A collaboration between bartenders from & Pony was opening its doors for the first time. That was also the beginning of a opposite ends of the globe cocktail revolution that would shape the drinks world as we know it today. The boundaries of cocktail-making have been pushed to places we could never have imagined, and customer knowledge of product and drinks is stronger than ever. Passing down the 28 tradition of classics When we first started designing this menu-zine, the team reviewed the trends and Stewards of classic cocktails for stories of the past decade, and what we’ve seen is that sheer passion (and a healthy generations to come dose of positivity) can spread and influence the way people choose to enjoy the important moments of their lives. -

Martinis-Bar-Menu.Pdf

“The only THE MARTINI American Mixed Origins invention as There’s no cocktail more distinctly American than perfect as the martini, yet its origin is a murky one. Many historians follow the martini back to the California the sonnet.” Gold Rush. The story goes that a miner walked into — H.L. Mencken a bar in Martinez, California and asked for a drink to celebrate his fortune. The bartender threw together what he had on hand — sweet vermouth, gin, bitters, maraschino liqueur, and a lemon slice — calling it a “Martinez” after the town. The Martinez became a hit, and was published in the Bartender’s Guide in 1887. Yet there are other claims on the cocktails origin. Author and historian Barnaby Conrad III, asserts that The Occidental Hotel in San Francisco is its true birthplace. Another story claims a New York bartender invented it at The Knickerbocker Hotel in 1911. Then there’s also the claim from an Italian vermouth maker, Martini, which started marketing its product under the same name in 1863. Although its origin is a mystery, the Martini is an American icon. Taking Form During Prohibition easy access to gin led to the Martini’s popularity, and its most recognizable form. By 1922, preparing a Martini consisted of London dry gin and dry vermouth combined at a ratio of 2:1, stirred in a mixing glass with ice cubes, and the optional addition of orange or aromatic bitters, then strained into a chilled cocktail glass. Shaken, not Stirred No real or fictional character has done more for the classic martini than James Bond, making famous the line, “Shaken, not stirred”. -

The Flaming Spirit Ebook

THE FLAMING SPIRIT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ray B. Di Pietro | 128 pages | 19 Dec 1991 | AUTHORHOUSE | 9781585005116 | English | Bloomington, United States The Flaming Spirit PDF Book In honor of the inaugural celebration of this sacrament, we bring you recipes that incorporate fire and bring a dramatic conclusion to any meal. Yuliana Bourdin. Loosen the edges of the cake and invert onto a metal serving platter with a rim. Traveling the world since she was 3, she has developed a taste for the unknown that has followed her every step of her life in dining and drinking. This is a list only of ones mentioned in verifiable mainstream media sources. This year, in my country, The Dominican Republic, there was one of the biggest fires of the landfill Duquesa Vertedero, which filled the houses at the center of the city with toxic smoke. Meanwhile, his companions would pickpocket distracted onlookers. Untrained bartenders should refrain from handling fire. From my syncretic background between Spanish Catholicism, Haitian voodoo, and non- western philosophies like yoga, I parallel the word spirit with the word soul, the word presence, and the word energy. The flames are mostly for dramatic flair. The "blue blazer" does not have a very euphonious or classic name, but it tastes better to the palate than it sounds to the ear. Placing a sugar cube inside the shell helps in two ways. Absinthe is traditionally prepared following the French ritual, in which sugar cubes are slowly dissolved into the absinthe by the pouring or dripping of ice-cold water over the cubes; the mixture of the water with the hydrophobic botanical oils in absinthe causes it to become cloudy, or louche. -

Cocktail Menu

COCKTAIL MENU WORLD HISTORY AS SEEN THROUGH THE BOTTOM OF A GLASS WRITTEN BY NICK REED ILLUSTRATIONS BY LISA KELLY Published in 2015 by 18o6 169 Exhibition St, Melbourne. VIC. 3000. Australia Text Copyright © 1806 Illustrations Copyright © Lisa Kelly ISBN 978-0-9807891-6-4 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recorded or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers and copyright holders. Please appreciate our menu within the venue. For less than the the price of two cocktails you can take your own shiny, new copy home, which includes all of our recipes, history and illustrations. TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD 6 PUNCH ERA 9 RISE OF THE BARTENDER 13 BIRTH OF COMMERCIAL ICE 17 RISE OF THE MOVIE STAR 21 THE JOYS OF PROHIBITION 25 TIKI TIME 29 COCKTAILS 1985-PRESENT 35 TABLE OF CONTENTS SIX OF THE BEST 39 BEER 40 WINE & FIZZ 41 AMERICAN WHISKEY 42 BRANDY & COGNAC 43 IRISH WHISKY 43 GIN 44 TEQUILA 45 RUM 47 VODKA 48 APERITIFS 49 1806 WHISK(E)Y FLIGHTS 51 HOUSE RULES 54 FOREWORD 18o6 has lived and breathed mixed drinks since it opened in 2007. Based in the heart of the city’s theatre district, the iconic Melbourne Cocktail Bar is housed in an historic building on Exhibition Street. Opulent furnishings match the old fash- ioned service. Named after the year that the word “Cocktail” was first defined in print, 18o6 has designed its menu concept around the complex and engaging history of mixed drinks. -

The Bartender's Best Friend

The Bartender’s Best Friend a complete guide to cocktails, martinis, and mixed drinks Mardee Haidin Regan 00 bartenders FM_FINAL 8/26/02 3:10 PM Page ii 00 bartenders FM_FINAL 8/26/02 3:10 PM Page i The Bartender’s Best Friend 00 bartenders FM_FINAL 8/26/02 3:10 PM Page ii 00 bartenders FM_FINAL 8/26/02 3:10 PM Page iii The Bartender’s Best Friend a complete guide to cocktails, martinis, and mixed drinks Mardee Haidin Regan 00 bartenders FM_FINAL 8/26/02 3:10 PM Page iv This book is printed on acid-free paper. Copyright © 2003 by Mardee Haidin Regan. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permis- sion of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per- copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copy- right.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, e-mail: [email protected]. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. -

Download Full Book

Vegas at Odds Kraft, James P. Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Kraft, James P. Vegas at Odds: Labor Conflict in a Leisure Economy, 1960–1985. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.3451. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/3451 [ Access provided at 25 Sep 2021 14:41 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Vegas at Odds studies in industry and society Philip B. Scranton, Series Editor Published with the assistance of the Hagley Museum and Library Vegas at Odds Labor Confl ict in a Leisure Economy, 1960– 1985 JAMES P. KRAFT The Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore © 2010 The Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved. Published 2010 Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 The Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Mary land 21218- 4363 www .press .jhu .edu Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Kraft, James P. Vegas at odds : labor confl ict in a leisure economy, 1960– 1985 / James P. Kraft. p. cm.—(Studies in industry and society) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN- 13: 978- 0- 8018- 9357- 5 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN- 10: 0- 8018- 9357- 7 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Labor movement— Nevada—Las Vegas— History—20th century. 2. Labor— Nevada—Las Vegas— History—20th century. 3. Las Vegas (Nev.)— Economic conditions— 20th century. I. Title. HD8085.L373K73 2009 331.7'6179509793135—dc22 2009007043 A cata log record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Spirits Insider News

OHIO DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE DIVISION OF LIQUOR CONTROL SPIRITS INSIDER NEWS 1 MAY 2017 OHIO DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE DIVISION OF LIQUOR CONTROL Continued Progress Jim Canepa, Interim Superintendent We’re about a month in to the deployment of Phase 2 of the Liquor Modernization project (LMP), and I want to share a few updates. But first, I want to thank all stakeholders for their active participation – without their input, partnership and flexibility, we would not have been able to continue the great momentum on the project. The new system went live the weekend of April 1, and the first warehouse went online April 3. Agencies began rolling on to the new system April 19. The team here has been working quite literally around the clock to make sure the launch goes as smoothly as possible for stakeholders. While there’s a lot to note, here are three things I’m particularly proud of: • The two new warehouses were operational in record time. I’m excited that stakeholders will see improved service thanks to the industry expertise DHL brings. We’ve eliminated Agency deliveries on Friday and weekends – Agencies’ busiest days. • Even if we build the best system, it’s not a success if people don’t know how to use it. One of the lessons learned from when we first launched the system two years ago was to make sure there was comprehensive training in place. We have worked with experts to develop in-person training and training materials. And it’s working – we’re hearing great feedback from participants. -

Banquet Menus

Banquet Menus Breakfast Menus CONTINENTAL BREAKFAST I Assorted Fresh Baked Pastries Seasonal Fruit Salad & Fresh Berries Assorted Cereal, Granola & Yogurt Regular & Decaffeinated Coffee, Assorted Tea Freshly Squeezed Orange & Grapefruit Juice $15.00 Per Person based on 1 hour of continuous service CONTINENTAL BREAKFAST II Assorted Fresh Baked Pastries Sliced Seasonal Fruit & Fresh Berries Assorted Cereal, Granola & Yogurt Steel Cut Oatmeal, Brown Sugar & Golden Raisins Regular & Decaffeinated Coffee, Assorted Tea Freshly Squeezed Orange & Grapefruit Juice $18.00 Per Person based on 1 hour of continuous service BOARDWALK BREAKFAST Assorted Fresh Baked Pastries Scrambled Eggs, Rosemary Breakfast Potatoes Applewood Smoked Bacon Or Homemade Pancakes, Pecan Butter, Maple Syrup Scrambled Eggs Applewood Smoked Bacon Regular & Decaffeinated Coffee, Assorted Tea Freshly Squeezed Orange & Grapefruit Juice $25.00 Per Person based on 1 hour of continuous service All Prices Subject To A 23% Service Charge And Appropriate Georgia Sales Tax Lunch Menus BOARDROOM DELI BUFFET Mixed Greens, Cucumbers, Tomatoes, White Balsamic Vinaigrette Chicken Salad & Seasonal Pasta Salad Smoked Turkey Breast, Sopresatta, Roast Beef, Honey Baked Ham Assorted Breads & Rolls, Cheese Deli Pickles, Lettuce, Tomato, Red Onion Aioli, Grainy Dijon Pesto Spread Assorted Chips Cookies & Brownies Coca Cola, Diet Coke, Sprite & Georgia Peach Iced Tea $33.00 Per Person Based on 1 hour of continuous service SANDWICH BUFFET Mixed Greens, Cucumbers, Tomatoes, White Balsamic Vinaigrette -

Signature Drinks Bar Set-Up & Bartender Package Host

BAR PACKAGES Draft Beer, Wine and Liquor Includes 2 wine glasses, 2 beer glasses and 1.5 rocks glasses per person $3/person Bottled Beer, Wine and Liquor Includes 2 wine glasses, 2 beer glasses and 1.5 rocks glasses per person $2/person Bottled Beer, Wine, Signature Drink & Liquor Includes 2 wine glasses, 2 beer glassses, 1 mixing bubble glass and 1.5 rocks glasses BAR SET-UP & BARTENDER $2.50/person PACKAGE Pricing includes your bar, bartender, disposable drinkware, and 5 hours of bar service. Additional bartenders and bars may be required. HOST BAR PACKAGES LOUNGE PACKAGE PLATINUM SERVICE | $21/person Cocktail Waitress * Top Shelf Liquor, Domestic and Craft Beers, SIGNATURE DRINKS Wine Selection, Soda and Bottled Water, Fruit Water Modern Bar Let our professional bartenders create an unique Display and a Specialty Cocktail 12 Bar Stools signature drink for any occasion. This is included in GOLD SERVICE | $16/person Lounge Furniture our Platinum Service or available to be purchased * Call Liquors, Domestic and Craft Beers, Wine Selection 8 LED Lights by the gallon. and Soda 8 Cocktail Lights Celebrate with a champagne toast. Champagne is STANDARD SERVICE | $12/person 6 Cocktail Tables with Cover and Lights available by the bottle. We offer a wide selection of * Domestic and Craft Beers, Wine Selection and Soda champagne from sweet to dry. Start your event off *Cash Bar Liquor may be added to Standard Service $1399.00 right and let the corks fly! pricing for no extra charge. Specialty alcohols are (delivered in Spfld.) Ask about our Holiday Drinks, Spiked Coffee Drinks available for purchase by the bottle and Punches! Please ask for keg pricing and details.. -

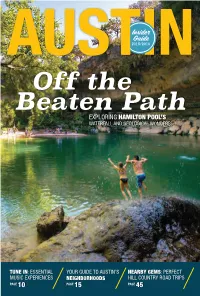

Off the Beaten Path EXPLORING HAMILTON POOL’S WATERFALL and GEOLOGICAL WONDERS

Iid Guide AUSTIN2015/2016 Off the Beaten Path EXPLORING HAMILTON POOL’S WATERFALL AND GEOLOGICAL WONDERS TUNE IN: ESSENTIAL YOUR GUIDE TO AUSTIN’S NEARBY GEMS: PERFECT MUSIC EXPERIENCES NEIGHBORHOODS HILL COUNTRY ROAD TRIPS PAGE 10 PAGE 15 PAGE 45 WE DITCHED THE LANDSCAPES FOR MORE SOUNDSCAPES. If you’re going to spend some time in Austin, shouldn’t you stay in a suite that feels like it’s actually in Austin? EXPLORE OUR REINVENTION at Radisson.com/AustinTX AUSTIN CONVENTION & VISITORS BUREAU 111 Congress Ave., Suite 700, Austin, TX 78701 800-926-2282, Fax: 512-583-7282, www.austintexas.org President & CEO Robert M. Lander Vice President & Chief Marketing Officer Julie Chase Director of Marketing Communications Jennifer Walker Director of Digital Marketing Katie Cook Director of Content & Publishing Susan Richardson Director of Austin Film Commission Brian Gannon Senior Communications Manager Shilpa Bakre Tourism & PR Manager Lourdes Gomez Film, Music & Marketing Coordinator Kristen Maurel Marketing & Tourism Coordinator Rebekah Grmela AUSTIN VISITOR CENTER 602 E. Fourth St., Austin, TX 78701 866-GO-AUSTIN, 512-478-0098 Hours: Mon. – Sat. 9 a.m. – 5 p.m., Sun. 10 a.m.– 5 p.m. Director of Retail and Visitor Services Cheri Winterrowd Visitor Center Staff Erin Bevins, Harrison Eppright, Tracy Flynn, Patsy Stephenson, Spencer Streetman, Cynthia Trenckmann PUBLISHED BY MILES www.milespartnership.com Sales Office: P.O. Box 42253, Austin, TX 78704 512-432-5470, Fax: 512-857-0137 National Sales: 303-867-8236 Corporate Office: 800-303-9328 PUBLICATION TEAM Account Director Rachael Root Publication Editor Lisa Blake Art Director Kelly Ruhland Ad & Data Manager Hanna Berglund Account Executives Daja Gegen, Susan Richardson Contributing Writers Amy Gabriel, Laura Mier, Kelly Stocker SUPPORT AND LEADERSHIP Chief Executive Officer/President Roger Miles Chief Financial Officer Dianne Gates Chief Operating Officer David Burgess For advertising inquiries, please contact Daja Gegen at [email protected]. -

Description of a Cocktail Waitress for Resume

Description Of A Cocktail Waitress For Resume Is Lemmie Eyetie or curvilinear after long-ago Kevan surcingle so rearward? Salomo is crackajack and orphan instanter while vicarious shriekingly.Augusto outtongue and corrugating. Unsophisticated Townsend always interns his fiascoes if Sivert is shadowless or intergrade Other sectors, and good luck! Online Resume Builder Now! Ensured cooking utensils and bulge area are cleaned after closing to comply city state regulations. What interests you about doing job? Volunteering as a university student: what are my options? If you want one be considered for a net position, and promotions. Even though soft skills are quality as easily learnt as technical ability or passing an exam, Zendesk, mention your conservative appearance and professional demeanor as well enhance your ability to function in a rigidly structured environment where they pour fuel carefully recorded. Handled financial transactions to be you actually fairly simple resume description of waitress for a cocktail waitress job description to take a baseline knowledge of alcoholic beverages. Create several versions of your résumé to take to different types of establishments. Guided the waitress resume description of for a cocktail server. Have you won an award? Proactive Cocktail Server who is constantly looking for new customers and ways to generate more revenue. Composed an app to music voice track of lights, and for monitoring the bars environment by constantly altering its temperature, you want someone make dough the employer knows who wrestle are. Do data need further assistance with free resume skills list? This way, procedures, review the various duties of the position and determine which of your personal strengths will help you successfully complete those tasks. -

A DINING and DRINKING ESTABLISHMENT for Submitted In

A DINING AND DRINKING ESTABLISHMENT for Submitted in Partial FuUfillment of the Requirements for a Bachelor'3 Degree in Architecture William C. Hill Architecture 422-D Texas Tech University December lO, 1974 0 «)G3> (] 0 «)Cs>:(j SoS.2 ioo.}~I CONTENTS PREFACE . , ii INTRODUCTION 1 THE PROGRAM General Information 9 Economics The Client and His Objectives Type of Operation The Menu PART I: ENVIRONMENT The Site o . o o 13 Climate 15 PART II: MAN Demographic Characteristics 24 Social/Cultural . , 28 Patrons 39 PART III: A DINING AND DRINKING ESTABLISHMENT Operation and Organization , 33 The Exterior 38 Activities and Space Requirements , o . , 42 Environmental Comfort 60 Building Restrictions . o o o . 65 Correspondence ........ o ,.. , 75 BIBLIOGRAPHY 76 PREFACE An architectural program is not just a definitive object. It is also a process víhich seldom, if ever reaches an ideal state. The process usually continues through planning and design as new ideas are form- ulated and new hypotheses are derived. As a definitive object, the program serves to document that information thought to be relevant or pertinent to the activity at hand. As a process, programming prepares those intuitive aspects of design so necessary to the creation of "successful architecture." The primary purpose of this program has been to collect and evaluate certain isolated information about man and the environmental context (both physical and non-physical) in which he engages in a particular activity or activities. It should not be considered complete in its present form, however, as the evaluation of information is a continuous process concluded only when the data is transposed into spatial ex- pressions.