Targum's Layout in Ashkenazic Manuscripts. Preliminary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moses Hayim Luzzatto's Quest for Providence

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 'Like Iron to a Magnet': Moses Hayim Luzzatto's Quest for Providence David Sclar Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/380 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] “Like Iron to a Magnet”: Moses Hayim Luzzatto’s Quest for Providence By David Sclar A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The City University of New York 2014 © 2014 David Sclar All Rights Reserved This Manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Prof. Jane S. Gerber _______________ ____________________________________ Date Chair of the Examining Committee Prof. Helena Rosenblatt _______________ ____________________________________ Date Executive Officer Prof. Francesca Bregoli _______________________________________ Prof. Elisheva Carlebach ________________________________________ Prof. Robert Seltzer ________________________________________ Prof. David Sorkin ________________________________________ Supervisory Committee iii Abstract “Like Iron to a Magnet”: Moses Hayim Luzzatto’s Quest for Providence by David Sclar Advisor: Prof. Jane S. Gerber This dissertation is a biographical study of Moses Hayim Luzzatto (1707–1746 or 1747). It presents the social and religious context in which Luzzatto was variously celebrated as the leader of a kabbalistic-messianic confraternity in Padua, condemned as a deviant threat by rabbis in Venice and central and eastern Europe, and accepted by the Portuguese Jewish community after relocating to Amsterdam. -

Etudes Sur Le Judaisme Medieval

Etudes sur le Judaisme Medieval Fondees par Georges Vajda Dirigees par Paul B. Fenton TOME XLIII Karaite Texts and Studies Edited by Meira Polliack Michael G. Wechsler VOLUME 2 BM6nnorpa(J)MH KapaMTMKa AHHOTMpoBaHHan 6n6nMorpa(J)MH KapaMMOB M KapanMM3Ma COCTaBMTeTIb Bappw Hob Ba/ic|)Miii npw ynacTHM Mwxaiina Kn3MjioBa m PlHCTMTyT BeH-U,BM Mepyca/iMM _ . • S ' ' 6 8 * ' BRILL JlewfleH • BOCTOH BpMTITI Bibliographia Karaitica An Annotated Bibliography of Karaites and Karaism By Barry Dov Walfish with Mikhail Kizilov m THE BEN-ZVI INSTITUTE JERUSALEM .0 • S ' ' 6 8 * ' BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2011 CONTENTS Preface to the Series ix Introduction liii Acknowledgements lix Mikhail Kizilov's Introduction lxi BBefleHwe (Russian Introduction) lxiii Abbreviations lxxiii Latin-Romanic lxxiii Cyrillic lxxvi Hebrew lxxvii Library Symbols lxxix Transliteration Tables lxxxi Hebrew lxxxi Arabic lxxxi Cyrillic lxxxii PART ONE GENERALIA CHAPTER ONE MANUSCRIPTS, ARCHIVES, BIBLIOGRAPHIES, PRINTING 1.1. Manuscript Lists and Library Holdings 3 1.1.1. General 3 1.1.2. Manuscripts in Private Collections 3 Medieval 3 Modern 3 Adler, E. N 4 Geiger, Abraham 4 Tischendorf, Konstantin von 5 1.1.3. Manuscripts in Public Collections 5 Western Europe 5 Austria 5 England 5 British Library, London 5 Cambridge 6 Germany—Leipzig 6 Netherlands—Leiden 6 Eastern Europe 6 Lithuania 6 Poland 7 Russia 7 General 7 Moscow 7 St. Petersburg 7 General 7 Institute of Oriental Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences 7 National Library of Russia 8 Firkovich Collections 8 Harkavy's Reports on the Firkovich Collections 11 Ukraine 15 Crimea 15 Bakhchisaray (Later Moved to Simferopol and Moscow) 15 Eupatoria (Yevpatoriya) 16 Xiv CONTENTS Sevastopol 16 Kiev 16 Odessa 16 1.1.4. -

אוסף מרמורשטיין the Marmorstein Collection

אוסף מרמורשטיין The Marmorstein Collection Brad Sabin Hill THE JOHN RYLANDS LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER Manchester 2017 1 The Marmorstein Collection CONTENTS Acknowledgements Note on Bibliographic Citations I. Preface: Hebraica and Judaica in the Rylands -Hebrew and Samaritan Manuscripts: Crawford, Gaster -Printed Books: Spencer Incunabula; Abramsky Haskalah Collection; Teltscher Collection; Miscellaneous Collections; Marmorstein Collection II. Dr Arthur Marmorstein and His Library -Life and Writings of a Scholar and Bibliographer -A Rabbinic Literary Family: Antecedents and Relations -Marmorstein’s Library III. Hebraica -Literary Periods and Subjects -History of Hebrew Printing -Hebrew Printed Books in the Marmorstein Collection --16th century --17th century --18th century --19th century --20th century -Art of the Hebrew Book -Jewish Languages (Aramaic, Judeo-Arabic, Yiddish, Others) IV. Non-Hebraica -Greek and Latin -German -Anglo-Judaica -Hungarian -French and Italian -Other Languages 2 V. Genres and Subjects Hebraica and Judaica -Bible, Commentaries, Homiletics -Mishnah, Talmud, Midrash, Rabbinic Literature -Responsa -Law Codes and Custumals -Philosophy and Ethics -Kabbalah and Mysticism -Liturgy and Liturgical Poetry -Sephardic, Oriental, Non-Ashkenazic Literature -Sects, Branches, Movements -Sex, Marital Laws, Women -History and Geography -Belles-Lettres -Sciences, Mathematics, Medicine -Philology and Lexicography -Christian Hebraism -Jewish-Christian and Jewish-Muslim Relations -Jewish and non-Jewish Intercultural Influences -

Maharam of Padua V. Giustiniani; the Sixteenth-Century Origins of the Jewish Law of Copyright

Draft: July 2007 44 Houston Law Review (forthcoming 2007) Maharam of Padua v. Giustiniani; the Sixteenth-Century Origins of the Jewish Law of Copyright Neil Weinstock Netanel* Copyright scholars are almost universally unaware of Jewish copyright law, a rich body of copyright doctrine and jurisprudence that developed in parallel with Anglo- American and Continental European copyright laws and the printers’ privileges that preceded them. Jewish copyright law traces its origins to a dispute adjudicated some 150 years before modern copyright law is typically said to have emerged with the Statute of Anne of 1709. This essay, the beginning of a book project about Jewish copyright law, examines that dispute, the case of the Maharam of Padua v. Giustiniani. In 1550, Rabbi Meir ben Isaac Katzenellenbogen of Padua (known by the Hebrew acronym, the “Maharam” of Padua) published a new edition of Moses Maimonides’ seminal code of Jewish law, the Mishneh Torah. Katzenellenbogen invested significant time, effort, and money in producing the edition. He and his son also added their own commentary on Maimonides’ text. Since Jews were forbidden to print books in sixteenth- century Italy, Katzenellenbogen arranged to have his edition printed by a Christian printer, Alvise Bragadini. Bragadini’s chief rival, Marc Antonio Giustiniani, responded by issuing a cheaper edition that both copied the Maharam’s annotations and included an introduction criticizing them. Katzenellenbogen then asked Rabbi Moses Isserles, European Jewry’s leading juridical authority of the day, to forbid distribution of the Giustiniani edition. Isserles had to grapple with first principles. At this early stage of print, an author- editor’s claim to have an exclusive right to publish a given book was a case of first impression. -

Twenty-Five Years at the Valmadonna Trust Library

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Hochschulschriftenserver - Universität Frankfurt am Main Twenty-Five Years at the Valmadonna Trust Library by Pauline Malkiel Librarian – Valmadonna Trust Library (London, England) When I first walked into the library in May 1982 I was struck initially by the smell of leather, then by the rows upon rows of fine bindings in burgundies, browns, beiges and creams packed neatly and tastefully on elegant open wooden shelves. Looking more closely I began to identify groupings: 16th century Italian locations with exciting names like Riva di Trento, Sabbionetta and Ferrara; whole areas of early Venetian printers – Bomberg, di Gara, Zanetti, each in its own space; a whole wall devoted to early Mediterranean printing in Salonika, Constantinople, and Prague, Lublin and Cracow. Then there were vast ranges of small liturgies of many different rites – Italian, Spanish, Roman, Ashkenazic, Aleppo, Karaite - sitting chronologically on shelves in beautiful bindings. Another area was devoted to Bibles printed in Venice starting in the year 1517. Placed in their own taller alcoves were stately volumes of Rabbinic Bibles and Maimonides Commentaries, Mishneh Torahs, Alfassi Commentaries in different editions, and, on closer inspection of the spines, many recurring titles such as ‘Semag,’ ‘Mizrachi,’’Rabenu Bechai,’’Perush HaTorah’ and endless Responsa. It was a thrill to see the word ‘unicum’ or ‘unique copy’ on a spine, and there were numerous slipcases containing ‘Variant 1’ and ‘Variant 2’ copies, promising intriguing revelations. Examining the spines one could decipher an exotic array of practically unheard-of place names: Kuru Tschesme, Prostitz, Isny, Constanz, Trino, Dordrecht, Pforzheim, Alcala de Henares and then, tucked away in a corner, all the very early 16th century Latin works printed by the Soncinos in Fano, Ortona, Pesaro, Cesena and so on. -

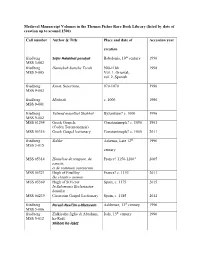

Medieval Manuscript Volumes in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library (Listed by Date of Creation up to Around 1500) Call Number Au

Medieval Manuscript Volumes in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library (listed by date of creation up to around 1500) Call number Author & Title Place and date of Accession year creation friedberg Sefer Halakhot pesuḳot Babylonia, 10 th century 1996 MSS 3-002 friedberg Ḥamishah ḥumshe Torah 900-1188 1998 MSS 9-005 Vol. 1, Oriental; vol. 2, Spanish. friedberg Kinot . Selections. 970-1070 1996 MSS 9-003 friedberg Mishnah c. 1000 1996 MSS 9-001 friedberg Talmud masekhet Shabbat Byzantium? c. 1000 1996 MSS 9-002 MSS 01244 Greek Gospels Constantinople? c. 1050 1901 (Codex Torontonensis) MSS 05316 Greek Gospel lectionary Constantinople? c. 1050 2011 friedberg Siddur Askenaz, Late 12 th 1996 MSS 3-015 century MSS 05314 Homeliae de tempore, de France? 1150-1200? 2005 sanctis, et de communi sanctorum MSS 05321 Hugh of Fouilloy. France? c. 1153 2011 De claustro animae MSS 03369 Hugh of StVictor Spain, c. 1175 2015 In Salomonis Ecclesiasten homiliæ MSS 04239 Cistercian Gospel Lectionary Spain, c. 1185 2012 friedberg Perush Neviʼim u-Khetuvim Ashkenaz, 13 th century 1996 MSS 5-006 friedberg Zidkiyahu figlio di Abraham, Italy, 13 th century 1996 MSS 5-012 ha-Rofè. Shibole ha-leḳeṭ friedberg David Kimhi. Spain or N. Africa, 13th 1996 MSS 5-010 Sefer ha-Shorashim century friedberg Ketuvim Spain, 13th century 1996 MSS 5-004 friedberg Beʼur ḳadmon le-Sefer ha- 13th century 1996 MSS 3-017 Riḳmah MSS 04404 William de Wycumbe. Llantony Secunda?, c. 1966 Vita venerabilis Roberti Herefordensis 1200 MSS 04008 Liber quatuor evangelistarum Avignon? c. 1220 1901 MSS 04240 Biblia Latina England, c. -

New Book Announcement: Amudim Be-Toldot Ha-Sefer Ha-Ivri (Volume Three)

New Book Announcement: Amudim be-Toldot ha-Sefer ha-Ivri (Volume Three) New Book Announcement: Amudim be-Toldot ha-Sefer ha-Ivri (Volume Three) By Eliezer Brodt I am very happy to announce the recent publication of an important work, which will be of great interest to readers of the Seforim blog. The third volume of, Amudim be-Toldot ha-Sefer ha-Ivri by Professor Yaakov Shmuel Spiegel, of Bar-Ilan University’s Talmud department. As I have written in the past, Professor Spiegel is one of the most prolific writers in the Jewish academic scene, authoring of over 160 articles and 18 books (16 of those are publications for the first time of works which remained in manuscript). Many suspect he possesses Hashbot Hakulmos (automatic writing). His articles cover an incredibly wide range of subjects related to many areas of Jewish Studies, including history of Rishonim,piyutim authored by Rishonim, bibliography and minhaghim, to name but a few. His uniqueness lies not only in the topics but also that his work has appeared in all types of publications running the gamut from academic journals such as Kiryat Sefer, Tarbiz, Sidra, Alei Sefer, Assufot, Teudah, Kovetz Al Yad and also in many prominent Charedi rabbinic journals such a Yeshurun, Yerushasenu, Moriah, Sinai and Or Yisroel. It is hard to define his area of expertise, as in every area he writes about he appears to be an expert! He has edited and printed from manuscript many works of Rishonim and Achronim on Massekhes Avos and the Haggadah Shel Pesach. He is of the opinion, contrary to that of some other academics, that there is nothing non- academic about printing critical editions of important manuscript texts. -

Bal Tashchit : the Jewish Prohibition Against Needless Destruction Wolff, K.A

Bal Tashchit : the Jewish prohibition against needless destruction Wolff, K.A. Citation Wolff, K. A. (2009, December 1). Bal Tashchit : the Jewish prohibition against needless destruction. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/14448 Version: Corrected Publisher’s Version Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/14448 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). BAL TASHCHIT: THE JEWISH PROHIBITION AGAINST NEEDLESS DESTRUCTION Copyright © 2009 by K. A. Wolff All rights reserved Printed in Jerusalem BAL TASHCHIT: THE JEWISH PROHIBITION AGAINST NEEDLESS DESTRUCTION Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. mr P.F. van der Heijden, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op dinsdag 1 december 2009 klokke 15:00 uur door Keith A. Wolff geboren te Fort Lauderdale (Verenigde Staten) in 1957 Promotiecommissie Promotores: Prof. Dr F.A. de Wolff Prof. Dr A. Wijler, Rabbijn, Jerusalem College of Technology Overige leden: Prof. Dr J.J. Boersema, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Prof. Dr A. Ellian Prof. Dr R.W. Munk, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Prof. Dr I.E. Zwiep, Universiteit van Amsterdam To my wife, our children, and our parents Preface This is an interdisciplinary thesis. The second and third chapters focus on classic Jewish texts, commentary and legal responsa, including the original Hebrew and Aramaic, along with translations into English. The remainder of the thesis seeks to integrate principles derived from these Jewish sources with contemporary Western thought, particularly on what might be called 'environmental' themes. -

Treasures of the Valmadonna Trust Library

TREASURES OF THE VALMADONNA TRUST LIBRARY A CATALOGUE OF 15TH-CENTURY BOOKS AND FIVE CENTURIES OF DELUXE HEBREW PRINTING EDITED BY DAVID SCLAR WITH BIBLIOGRAPHIC STUDIES BY BRAD SABIN HILL ADRI K. OFFENBERG ISAAC YUDLOV David Sclar, Editor אוצרות יעקב Sharon Liberman Mintz, Project Director Pauline Malkiel, Librarian of the Valmadonna Trust Library CONTRIBUTORS: Brad Sabin Hill, Curator of the I. Edward Kiev Judaica Collection, The George Washington University, Washington, DC Adri K. Offenberg, Emeritus Curator of the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana, University of Amsterdam Isaac Yudlov, Director of the Institute for Hebrew Bibliography, Jerusalem ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: Shimon Iakerson, Head Researcher, Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of the Russian Academy of Sciences Ari Kinsberg, Independent Scholar David N. Redden, Vice Chairman, Sotheby’s NY, and the Staff of the Sotheby’s NY Book Department Jerry Schwarzbard, Librarian for Special Collections, The Library of The Jewish Theological Seminary David Wachtel, Senior Consultant for Judaica, Sotheby’s NY Design: Jean Wilcox, Wilcox Design Photography: Ardon Bar-Hama Indexes: Warren Klein Printing: Kirkwood Printing © 2011 London & New York Valmadonna Trust Library FOREWORD 6 INTRODUCTION David Sclar 7 Dedicated to the memory of my teacher and friend, THE HONEYCOMB’S FLOW: H E B R E W I N C U N A B L E S IN THE VALMADONNA TRUST LIBRARY Adri K. Offenberg Professor Chimen Abramsky. 10 Jack V. Lunzer I N C U N A B L E S 28 HEBREW BOOKS PRINTED ON VELLUM IN THE VALMADONNA TRUST LIBRARY Isaac Yudlov 52 BOOKS PRINTED ON VELLUM 62 HEBREW PRINTING ON BLUE AND OTHER COLOURED PAPERS Brad Sabin Hill 84 BOOKS PRINTED ON COLOURED PAPER 112 BOOKS PRINTED ON SILK 148 BOOKS PRINTED IN RED INK 150 INDEXES 152 BIBLIOGRAPHY 164 6 7 FOREWORD INTRODUCTION This volume is the tenth in a series of bibliophile editions, facsimiles, and catalogues of early and ‘Make your books your companions. -

Of the Mishnah, Bavli & Yerushalmi

0 Learning at SVARA SVARA’s learning happens in the bet midrash, a space for study partners (chevrutas) to build a relationship with the Talmud text, with one another, and with the tradition—all in community and a queer-normative, loving culture. The learning is rigorous, yet the bet midrash environment is warm and supportive. Learning at SVARA focuses on skill-building (learning how to learn), foregrounding the radical roots of the Jewish tradition, empowering learners to become “players” in it, cultivating Talmud study as a spiritual practice, and with the ultimate goal of nurturing human beings shaped by one of the central spiritual, moral, and intellectual technologies of our tradition: Talmud Torah (the study of Torah). The SVARA method is a simple, step-by-step process in which the teacher is always an authentic co-learner with their students, teaching the Talmud not so much as a normative document prescribing specific behaviors, but as a formative document, shaping us into a certain kind of human being. We believe the Talmud itself is a handbook for how to, sometimes even radically, upgrade our tradition when it no longer functions to create the most liberatory world possible. All SVARA learning begins with the CRASH Talk. Here we lay out our philosophy of the Talmud and the rabbinic revolution that gave rise to it—along with important vocabulary and concepts for anyone learning Jewish texts. This talk is both an overview of the ultimate goals of the Jewish enterprise, as well as a crash course in halachic (Jewish legal) jurisprudence. Beyond its application to Judaism, CRASH Theory is a simple but elegant model of how all change happens—whether societal, religious, organizational, or personal. -

What Is Coveting?

What is coveting, and what’s wrong with it? Is coveting a feeling or an action? 1) In the book of Exodus it says, Do not covet [lo tachmod] your neighbor’s house; do not covet your neighbor’s wife or male or female servant, or his ox or his donkey, or anything that is your neighbor’s (Ex. 20:14). Later, in Deuteronomy (in the restatement of the Ten Commandments), it says Do not covet your neighbor’s wife; and do not crave [lo titaveh] you neighbor’s house, or his field, or his male or female servant, or his ox or his donkey, or anything that is your neighbor’s (Deut. 5:18). This indicates that both “crave” and “covet” are culpable actions. From where do we learn that if a person craves, it will lead to coveting? Because it says do not covet – do not crave. Where do we learn that if a person covets, it leads to theft? As it is written, They will covet fields and rob (Micah 2:2). Craving, ta’avah, is in the heart, as it is written, Your soul will have the craving to eat meat (Deut. 12:20), and coveting, chimud, has to do with action, as it is written, You shall not covet the silver and gold upon them [their idols] and take it for yourself (Deut. 7:25). (Mekhilta, early rabbinic midrash) 2) Whoever covets her fellow’s servant, house, utensils, or any saleable article of his, pressuring him until he agrees to part with it, even though she pays him well for it, has violated the negative mitzvah of “Do not covet.”…She is not liable on this count until she actually takes possession of the article she coveted. -

F Ine J Udaica

F INE J UDAICA . HEBREW PRINTED BOOKS, MANUSCRIPTS &CEREMONIAL ART K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY TUESDAY, JUNE 29TH, 2004 K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art Lot 340 Catalogue of F INE J UDAICA . HEBREW PRINTED BOOKS, MANUSCRIPTS &CEREMONIAL ART Including Judaic Ceremonial Art: From the Collection of Daniel M. Friedenberg, Greenwich, Conn. And a Collection of Holy Land Maps and Views To be Offered for Sale by Auction on Tuesday, 29th June, 2004 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand on Sunday, 27th June: 10:00 am–5:30 pm Monday, 28th June: 10:00 am–6:00 pm Tuesday, 29th June: 10:00 am–2:30 pm Important Notice: The Exhibition and Sale will take place in our New Galleries located at 12 West 27th Street, 13th floor, New York City. This Sale may be referred to as “Sheldon” Sale Number Twenty Four. Illustrated Catalogues: $35 • $42 (Overseas) KESTENBAUM & COMPANY Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 12 West 27th Street, 13th Floor, New York, NY 10001 • Tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 E-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web Site: www.Kestenbaum.net K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager & Client Accounts: Margaret M. Williams Press & Public Relations: Jackie Insel Printed Books: Rabbi Bezalel Naor Manuscripts & Autographed Letters: Rabbi Eliezer Katzman Ceremonial Art: Aviva J. Hoch (Consultant) Catalogue Photography: Anthony Leonardo Auctioneer: Harmer F. Johnson (NYCDCA License no. 0691878) ❧ ❧ ❧ For all inquiries relating to this sale please contact: Daniel E. Kestenbaum ❧ ❧ ❧ ORDER OF SALE Printed Books: Lots 1 – 224 Manuscripts: Lots 225 - 271 Holy Land Maps: Lots 272 - 285 Ceremonial Art:s Lots 300 - End of Sale Front Cover: Lot 242 Rear Cover: A Selection of Bindings List of prices realized will be posted on our Web site, www.kestenbaum.net, following the sale.