A/71/187 General Assembly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rebel Forces in Northern Mali

REBEL FORCES IN NORTHERN MALI Documented weapons, ammunition and related materiel April 2012-March 2013 Co-published online by Conflict Armament Research and the Small Arms Survey © Conflict Armament Research/Small Arms Survey, London/Geneva, 2013 First published in April 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of Conflict Armament Research and the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organisation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the secretary, Conflict Armament Research ([email protected]) or the secretary, Small Arms Survey ([email protected]). Copy-edited by Alex Potter ([email protected]) Reviewed by Alex Diehl and Nic Jenzen-Jones Cover image: © Joseph Penny, 2013 Above image: Design and layout by Julian Knott (www.julianknott.com) © Richard Valdmanis, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS About 4 3.7 M40 106 mm recoilless gun 11 Abbreviations and acronyms 5 4. Light Weapons Ammunition 12 Introduction 6 4.1 12.7 x 108 mm ammunition 12 4.2 14.5 x 115 mm ammunition 12 1. Small Arms 7 4.3 PG-7 rockets 13 1.1 Kalashnikov-pattern 7.62 x 39 mm assault 4.4 OG-82 and PG-82 rockets 13 rifles 7 4.5 82 mm mortar bombs 14 1.2 FN FAL-pattern 7.62 x 51 mm rifle 7 4.6 120 mm mortar bombs 14 1.3 G3-pattern 7.62 x 51 mm rifle 7 4.7 Unidentified nose fuzes 14 1.4 MAT-49 9 x 19 mm sub-machine gun 7 4.8 F1-pattern fragmentation grenades 15 1.5 RPD-pattern 7.62 x 39 mm light 4.9 NR-160 106 mm HEAT projectiles 15 machine gun 7 1.6 PK-pattern 7.62 x 54R mm general-purpose 5. -

Artillery Ammunition from the 1781 Siege of Star Fort

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Archaeology and Anthropology, South Carolina Faculty & Staff Publications Institute of 9-2020 Artillery Ammunition from the 1781 Siege of Star Fort James B. Legg Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sciaa_staffpub Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, and the Military History Commons Research Artillery Ammunition from the 1781 Siege of Star Fort By James B. Legg th Regular readers of Legacy, will recall that daily feature of the siege. By June 18 , the The 6-pounder was the standard field in 2018 and 2019, SCIAA Director Steve Americans were entrenched immediately caliber used by both British and American Smith conducted USC “Maymester” north of the ditch of Star Fort, but a large artillery during the Revolution. Historical archaeological field schools in and around relief force of British regular troops was sources indicate that the Americans used Star Fort, a component of the 1781 British on its way to break the siege. Greene at least four, 6-pounder field guns in defenses of Ninety Six, South Carolina, at decided to risk a direct assault on Star Fort the siege of Star Fort, while the British Ninety Six National Historic Site (Figures before giving up the siege, but the attack had only two or three 3-pounders, and 1 and 2). The work included formal met with a bloody repulse. Greene broke possibly some very light-caliber swivel excavation units, and an array of metal off the siege and withdrew the following guns. Nevertheless, we found both detector sample areas. Among our findings day, but the British then decided that the American and British 6-pounder shot in was a significant assemblage related to the post of Ninety Six was too exposed to be Star Fort. -

Firearms Evidence Collection Procedures

FIREARMS EVIDENCE COLLECTION PROCEDURES INTRODUCTION: Firearms evidence is usually encountered in crimes against persons such as homicide, assault and robbery; but may also be found in other crimes such as burglary, rape, and narcotics violations. While comparisons of bullets and cartridge cases to specific firearms are the most common examinations requested, other examinations are possible such as: distance determinations based on powder residue or shot spread; examination of firearms for functioning or modification; sequence of shots fired and trajectories; list of possible weapons used; serial number restoration and ownership tracing. Evidence of firing or handling a firearm may be detected through the analysis of gunshot residue collected from a persons hands or other body surfaces. (see PEB 15 12/90). EVIDENCE FIREARMS-HANDLING AND SAFETY: The location and condition of firearms and related evidence at a crime scene should be diagramed and photographed before recovering and securing. Although physical evidence is important, safety must be the first consideration. Each situation should be evaluated before deciding to unload an evidence firearm. (Caution, treat a firearm at all times as if it were loaded). If the weapon is a type that can be safely transported in a loaded condition, this can be done. However, depending on the circumstances it may be unnecessary or unwise to transport a loaded firearm. It should then be unloaded, with care taken to preserve all types of possible evidence. This evidence includes fingerprints, blood, hair or fibers, cylinder "halos", and debris in the barrel and/or cylinder. The weapon should be handled on those areas least likely to retain latent fingerprints such as knurled or checkered areas. -

Worldwide Equipment Guide

WORLDWIDE EQUIPMENT GUIDE TRADOC DCSINT Threat Support Directorate DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution unlimited. Worldwide Equipment Guide Sep 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Page Memorandum, 24 Sep 2001 ...................................... *i V-150................................................................. 2-12 Introduction ............................................................ *vii VTT-323 ......................................................... 2-12.1 Table: Units of Measure........................................... ix WZ 551........................................................... 2-12.2 Errata Notes................................................................ x YW 531A/531C/Type 63 Vehicle Series........... 2-13 Supplement Page Changes.................................... *xiii YW 531H/Type 85 Vehicle Series ................... 2-14 1. INFANTRY WEAPONS ................................... 1-1 Infantry Fighting Vehicles AMX-10P IFV................................................... 2-15 Small Arms BMD-1 Airborne Fighting Vehicle.................... 2-17 AK-74 5.45-mm Assault Rifle ............................. 1-3 BMD-3 Airborne Fighting Vehicle.................... 2-19 RPK-74 5.45-mm Light Machinegun................... 1-4 BMP-1 IFV..................................................... 2-20.1 AK-47 7.62-mm Assault Rifle .......................... 1-4.1 BMP-1P IFV...................................................... 2-21 Sniper Rifles..................................................... -

Artillery Ammunition

38 Artillery Ammunition INVESTMENT COMPONENT Modernization MISSION Separate-loading ammunition, used SYSTEM INTERDEPENDENCIES Provides field artillery forces with in 155mm howizters, has separately None Recapitalization modernized munitions to destroy, issued projectiles, fuzes, propellant charges, and primers. PROGRAM STATUS Maintenance neutralize, or suppress the enemy by • 3QFY12: Full Materiel Release of cannon fire. After installing the appropriate fuze the M1122, 155mm high-explosive DESCRIPTION on the projectile, the fuzed projectile projectile The Army’s artillery ammunition is loaded into the cannon along with program includes 75mm (ceremonies the appropriate amount of propellant PROJECTED ACTIVITIES and simulated firing), 105mm, and charges and a primer. • 3QFY13: Type Classification of the 155mm projectiles and their associated M1123/M1124 155mm illumination fuzes and propelling charges. The artillery ammunition program projectiles includes fuzes for cargo-carrying Semi-fixed ammunition for short projectiles, such as smoke and and intermediate ranges, used in illumination, and bursting projectiles, 105mm howitzers, is characterized such as high explosives. by adjusting the number of multiple propelling charges. Semi-fixed This program also includes bag ammunition for long ranges contains propellant for the 105mm semi-fixed a single bag of propellant optimized cartridges and a modular artillery for obtaining high velocity and is charge system for 155mm howitzers. not adjustable. The primer is an integral part of the cartridge -

ATF Guidebook - Importation & Verification of Firearms, Ammunition, and Implements of War

U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives ATF Guidebook - Importation & Verification of Firearms, Ammunition, and Implements of War Contents 2 • • This publication was prepared by the Firearms and Explosives Imports Branch (FEIB), Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) to assist Importers and other Firearms Industry Members in identifying firearms, ammunition, and defense articles that may be imported into the United States and to further clarify and facilitate the import process. The FEIB Guidebook was developed to provide guidance in the importation process through the proper recognition and correct use of required forms, regulatory policies, and prescribed import procedures. This guide presents a comprehensive overview of the importation process and provides both relevant and definitive explanations of procedural functions by outlining the existing imports controls including the Arms Export Control Act (AECA), the National Firearms Act (NFA) and the Gun Control Act (GCA). If there are any additional questions or further information is needed, please contact the Firearms and Explosives Imports Branch at (304) 616-4550. Select a category to proceed. Select the down arrow to expand the category. Select the same arrow to collapse the category. • How To Use This Guidebook • General Overview • Policies & Procedures ◦ Policies & Procedures Overview Contents 3 ◦ Import Requirements for Firearms & Ammunition ◦ ATF 4590 – Factoring Criteria for Weapons ◦ Restricted Importation ◦ Conditional -

Firearms Classification

Classification This section contains descriptions of key concepts to be used in the completion of the Seizures Questionnaires. For the purposes of the Seizures Questionnaires only, the following terms shall have the following meanings: “Firearm” shall mean any portable barrelled weapon that expels, is designed to expel or may be readily converted to expel a shot, bullet or projectile by the action of an explosive, excluding antique firearms or their replicas. Antique firearms and their replicas shall be defined in accordance with domestic law. In no case, however, shall antique firearms include firearms manufactured after 1899. “Parts and components” shall mean any element or replacement element specifically designed for a firearm and essential to its operation, including a barrel, frame or receiver, slide or cylinder, bolt or breech block, and any device designed or adapted to diminish the sound caused by firing a firearm; “Ammunition” shall mean the complete round or its components, including cartridge cases, primers, propellant powder, bullets or projectiles, that are used in a firearm Types of firearms Rifle A relatively long-barreled firearm, fired from the shoulder, having a series of spiral grooves cut inside the barrel (a process called ‘ rifling ’) imparting a rapid spin to a single projectile. Shotgun A shoulder-fired long gun with no rifling in the barrel, designed to shoot a large number of small projectiles (“shot”) rather than a single large projectile (“a bullet”). Machine gun A machine gun is a fully-automatic firearm. This means the weapon will continue to load and fire ammunition until the trigger, or other activating device, is released, the ammunition is exhausted, or the firearm is jammed. -

Application & Permit for Importation of Firearms, Ammunition

OMB No. 1140-0005 (12/31/2022) U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives Application and Permit for Importation of Firearms, Ammunition and Defense Articles Not for use by Members of the United States Armed Forces. For ATF Use Only For Applicant's Optional Use Permit No. (Valid for 24 months from the date appearing in Item 19 below.) NPR No. Internal Control/Reference # E-mail Address (Optional) Section I - Application (Submit in triplicate) - For Applicant Use 1. Federal Firearms License (If Any) 2. Telephone No. (Including 3. Country of Exportation License No. (x-xx-xxx-xx-xx-xxxxx) Expiration Date Extension No.) 4. Name and Address of Customs Broker (Including Zip Code) 5. Applicant's Name and Address (Including Zip Code) Check here if permit is to be returned to Customs Broker. Check here if permit is to be returned to applicant. 6. Name and Address of Foreign Seller, if any 7. Name and Address of Foreign Shipper 8. Description of Firearms and Ammunition (For firearms, enter (SG)-Shotgun; (RI)-Rifle; (PI)-Pistol; (RE)-Revolver; (DD)-Destructive Device; (MG)-Machinegun) Name and Address of Manufacturer Type Caliber Quantity Unit U.S. Muni- Model Length Overall Serial New (N) City and State (Frame, Gauge (Each type) Cost (U.S. tions Import (required) of Length No. or or Receiver, or Size Currency) List Barrel (Inches) Used (U) City and Country SG, RI, PI, (Inches) RE,DD,MG) Category a. b. c. d. e. f. g. h. i. j. k. Firearms Firearms See Attachment Description 9. Certification of Origin. -

Quick Reference to Federal Firearms Laws

QUICK REFERENCE TO FEDERAL FIREARMS LAWS I. POSSESSION OF A FIREARM OR AMMUNITION BY A PROHIBITED PERSON: 18 USC § 922(g) & (n). Punishable by up to 10 years imprisonment. May receive minimum sentence of 15 years without parole if offender has three or more prior convictions for a felony crime of violence (e.g. burglary, robbery, assault, possession of offensive weapons) and/or drug trafficking felony. Elements A. Possession or receipt of a firearm or ammunition; B. By a subject who falls within one of the following categories: Felon - (Additionally, persons awaiting trial on felony charges are prohibited from receiving firearms.); Drug user or addict - (Often shown where paraphernalia seized, subject tests positive for drugs and/or subject claims drugs were possessed for personal use.); Alien - (Includes illegal aliens and aliens lawfully admitted under non-immigrant visas, i.e., those aliens not admitted for permanent residence. This provision does not prohibit aliens who lawfully possess a so-called “green card” from possessing guns or ammunition.); Is subject to a domestic restraining order - (The order must prohibit contact with an intimate partner, or child of the subject, and must have been issued only after a hearing of which the subject was notified and at which the subject had an opportunity to participate. The order must also find the subject poses a threat to the physical safety of the intimate partner or child or must prohibit the use, threatened use or attempted use of physical force.); Has a prior conviction for domestic assault - (Includes a prior conviction for any assault or threatened use of a deadly weapon against a present or former spouse or partner or child or guardian of any such person. -

High Tech Bullets and Slugs

High-Tech Bullets and Slugs Non-Lead Ammunition for… Good Hunting Improved Conservation High-Quality Meat Non-Lead Ammunition: A Better Choice Soft, easily molded and heavy, lead has long been the most common type of ammunition. With early firearms such as muzzleloaders, lead bullets retained their shape, but modern, higher-velocity centerfire rifles often cause lead bullets (even those sheathed in copper) to fragment upon impact. Fortunately, today’s harder copper and other copper alloy bullets and slugs typically remain intact on impact, transferring more energy to the target by folding downward into “petals” that greatly expand the surface area. The result is a very effective, quick, humane kill and more edible, uncontaminated meat. Fragmentation vs. Mushrooming (Photo courtesy of William E. Cornatzer) Comparison of two .270-caliber Shotgun slugs made of copper CT-scan showing lead Radiograph of a deer’s chest bullets shot into a modified rain fold into “petals,” expanding fragments (appearing white) illustrating fragmentation of a barrel for collection to simulate the slug’s surface area better in 20 one-pound packages of lead ballistic tip rifle bullet. performance on game. The than slugs made of lead. ground venison. copper jacket lead-core bullet (left) is heavily fragmented compared to the solid copper bullet (right) that retained its original shape upon impact. Lead’s Risk LEAD for People and Wildlife NON-LEAD When lead and lead-core bullets fragment on impact, hundreds of tiny lead particles scatter throughout the tissue–up to 18 inches from the wound. Some of these fragments are too small to be seen, felt, tasted, or removed. -

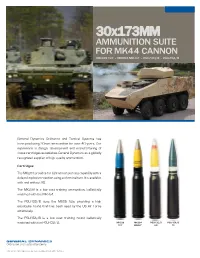

30X173mm AMMUNITION SUITE for MK44 CANNON MK239 TP-T - MK264 MPLD-T - PGU-13D/B - PGU-15A/B

30x173MM AMMUNITION SUITE FOR MK44 CANNON MK239 TP-T - MK264 MPLD-T - PGU-13D/B - PGU-15A/B General Dynamics Ordnance and Tactical Systems has been producing 30mm ammunition for over 40 years. Our experience in design, development and manufacturing of these cartridges establishes General Dynamics as a globally recognized supplier of high quality ammunition. Cartridges The MK264 provides for light armor piercing capability with a delayed explosive reaction using a chemical fuze. It is available with and without SD. The MK239 is a low cost training ammunition, ballistically matched with the MK264. The PGU-13D/B uses the M505 fuze, providing a high expolosive round that has been used by the US Air Force extensively. The PGU-15A/B is a low cost training round ballistically matched with the PGU-13D/B. MK239 MK264 PGU-13D/B PGU-15A/B TP-T MPLD-T* HEI TP * MK258 and MK264 are produced in collaboration with Nammo. 30x173MM AMMUNITION SUITE FOR MK44 CANNONAMMUNITION SUITE FOR MK44 CANNON MK239 TP-T - MK264 MPLD-T - PGU-13D/B - PGU-15A/B 30x173mm Ammunition Family for MK44 Cannon MK239 MK264 PGU-15A/B PGU-13D/B Target Multipurpose Target High Explosive Practice, Low Drag - Practice Incendiary (HEI) Tracer Tracer (TP) (TP-T) (MPLD-T) Caliber 30x173mm 30x173mm 30x173mm 30x173mm Type TP-T MPLD-T Incendiary TP HEI Cartridge Length 290mm 290mm 290mm 290mm Cartridge Weight 670g 835g 670g 670g Projectile Weight 365g 363g 363g 363g Propellant Weight 153g 150g 147g 147g Case Length 173mm 173mm 173mm 173mm Case Material Aluminum Aluminum Aluminum Aluminum -

Ammunition Handbook Edition 6

AMMUNITION HANDBOOK Edition 6, May 2021 WE ARE NAMMO Nammo is an international aerospace and defense company headquartered in Norway. With over 2 700 employees across more than 34 sites and offices in 12 countries, we are one of the world’s leading providers of ammunition and rocket motors for both military and civilian customers. Nammo was formed in 1998 through a merger of ammunition businesses in Norway, Sweden and Finland, and today is owned equally by the Norwegian Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries and the Finnish aerospace and defense company Patria Oyj. Nammo manufactures superior quality ammunition for some of the world's most demanding customers, both military and civilian. Our product portfolio includes shoulder-launched munitions systems, ammunition for military applications, sports shooting and hunting, rocket motors for military and space applications, and environmentally friendly demilitarization services. Defense accounts for 80 percent of our income, and 20 percent is from civilian activities including commercial ammunition, space propulsion and sea safety. www.nammo.com 3 [email protected] SMALL CALIBER AMMUNITION CORE BUSINESS Ammunition Nammo is a superior quality producer of small, medium and large caliber ammunition products. Shoulder-Fired Systems Nammo has a broad range of shoulder-fired systems covering most of the warfighters’ needs in today’s scenarios. Rocket Motors Nammo has unique competence within engineering, analysis and manufacturing of high-performance rocket motors and space applications. Demilitarization Nammo is a world leader within environmentally friendly demilitarization. www.nammo.com 4 [email protected] 5 CORE BUSINESS CONTENTS SMALL CALIBER AMMUNITION MAKING NATO CALIBERS MORE EFFECTIVE AND SAFE .................................................