University of Birmingham Local Governance, Disadvantaged

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Balsall Heath Neighbourhood Development Plan 2015 – 2031

Balsall Heath Neighbourhood Development Plan 2015 – 2031 Consultation Statement 1 Balsall Heath Neighbourhood Development Plan Consultation Statement This document is a record of the various stages and forms of consultation, statutory and non-statutory, which have been carried out during the making of the NDP, between 2011 and 2014. Contents Introduction, and summary of the three stages of consultation Page 3 Stage 1: initial consultation Page 5 Stage 2: consultation on draft proposals Page 22 Stage 3: pre-submission consultation Page 25 Appendix 1: Prince’s Foundation Workshop report Appendix 2: Reductions of the Stage 2 exhibition panels Appendix 3: Articles from The Heathan Appendix 4: Consultation Feedback Forms Appendix 5: Consultee List 2 1 Introduction 1.1 Balsall Heath, despite being among the UK’s 20% most deprived neighbourhoods, has a cohesive social structure, characterised by the existence of many social, religious, educational and business networks. These have been developed significantly over the past 30 years, largely by the efforts of local organisations such as Balsall Heath Forum and St Paul’s Community Trust. Many local people have been involved in constructive processes by which the social, environmental and economic conditions of Balsall Heath have been improved. People are used to being consulted, and this has been to the advantage of the NDP, which has used existing networks as a basis for the various stages of consultation. 1.2 Consultation processes have been consistent with the City Council’s policy Statement of Community Involvement (2008), which sets criteria and methods by which citizens are enabled and encouraged to be involved in planning issues. -

Harbury Road, Balsall Heath, Birmingham, West Midlands, B12 9NQ Asking Price £280,000

EPC C Harbury Road, Balsall Heath, Birmingham, West Midlands, B12 9NQ Asking Price £280,000 A modern four bedroom terraced property Located in Balsall Heath, close to Edgbaston cricket ground, Moseley Village and Cannon Hill Park. Public transport links into Birmingham City Centre and Selly Oak, (QE Hospital) are close by and local amenities are all within walking distance including a pharmacy. Perfect family home or investment opportunity as currently is let, great for someone looking for a property that has been recently built, and ready to move in to! It has two spacious reception rooms, a large kitchen with separate utility/laundry room and access into the garden. Upstairs over two floors are four double bedrooms, one with en suite shower room, one with en suite WC and a family shower room on the first floor. The property also benefits from a garage to the rear and a parking space, viewing is recommended to see the space available in this house. https://www.dixonsestateagents.co.uk Viewing arrangement by appointment 0121 449 6464 [email protected] Dixons, 95 Alcester Road, Moseley Interested parties should satisfy themselves, by inspection or otherwise as to the accuracy of the description given and any floor plans shown in these property details. All measurements, distances and areas listed are approximate. Fixtures, fittings and other items are NOT included unless specified in these details. Please note that any services, heating systems, or appliances have not been tested and no warranty can be given as to their working order. A member of Countrywide plc. Countrywide Estate Agents, trading as Dixons, registered office: Countrywide House, 88-103 Caldecotte Lake Drive, Caldecotte, Milton Keynes, MK7 8JT. -

Balsall Heath Neighbourhood Development Plan

Appendix 4 BALSALL HEATH NEIGHBOURHOOD DEVELOPMENT PLAN Basic Conditions Statement The accompanying draft Plan is submitted by a qualifying body The Balsall Heath Neighbourhood Development Plan (NDP) is submitted by the Balsall Heath Neighbourhood Planning Forum, which is a neighbourhood forum that meets the requirements of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended by the Localism Act) and has been designated as such by the local planning authority. Written confirmation of the designation by Birmingham City Council is included as an appendix. What is being proposed is a neighbourhood development plan The proposals in this NDP relate to planning matters (the use and development of land) and has been prepared in accordance with the statutory requirements and processes set out in the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended by the Localism Act 2011) and the Neighbourhood Planning Regulations 2012. The proposed neighbourhood plan states the period for which it is to have effect It is confirmed that the plan specifies a time period for which it will be in force, namely 2014 to 2031, the latter being the time horizon for the draft Birmingham Development Plan (Local Plan/Core Strategy). The policies do not relate to excluded development The neighbourhood plan proposal does not deal with nationally significant infrastructure or any other matters set out in Section 61K of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990. The proposed neighbourhood plan does not relate to more than one neighbourhood area and there are no other neighbourhood development plans in place within the neighbourhood area. The neighbourhood plan proposal relates to the Balsall Heath Neighbourhood Area – as approved by Birmingham City Council – and to no other area. -

Food Banks / Clothes Banks

Food Banks / Clothes Banks Trussell Trust (Red Vouchers - If you do not know where to go to obtain a red Trussell Trust food voucher please contact either of the following telephone money / debt advice services. Citizens Advice Bureau 03444 771010. or. Birmingham Settlement Free Money Advice 0121 250 0765.) Voucher required Address Phone / E-mail Opening Central Foodbank 0121 236 2997 Fri 10am – 1.30pm Birmingham City Church Parade [email protected] B1 3QQ (parking B1 2RQ – please ensure you enter your vehicle registration on site before you leave the building to avoid a parking fine). Erdington Foodbank Six 07474 683927 Thurs 12.00 – 14.00 Ways Baptist Church Wood End Rd, Erdington [email protected] Birmingham B24 8AD George Road Baptist 07474 683927 Tues 12.00 – 14.00 Church George Road Erdington B23 7RZ [email protected] New Life Wesleyan 0121 507 0734 Thurs 13.00 – 15.00 Church Holyhead Rd, [email protected] Handsworth, Birmingham B21 0LA Sparkhill Foodbank 0121 708 1398 Thu 11.00 – 13.00 Balsall Heath Satellite [email protected] Balsall Heath Church Centre 100 Mary Street Balsall Heath Birmingham B12 9JU 1 Great Barr Foodbank St 0121 357 5399 Tues 12.00 – 14.00 Bernard's Church [email protected] Fri 12.00 – 14.00 Broome Ave, Birmingham B43 5AL Aston & Nechells 0121 359 0801 Mon 12 – 14.30 Foodbank St Matthews [email protected] Church 63 Wardlow Rd, Birmingham B7 4JH Aston & Nechells 0121 359 0801 Fri 12.30 – 14.30 Foodbank The Salvation Army Centre Gladstone [email protected] Street Aston Birmingham B6 7NY Non-Trussell Trust (No red voucher required) Address Phone / E-mail / Web-site Opening Birmingham City 0121 766 6603 (option 2) Mon – Fri 10am – Mission 2pm to speak to Puts you through to Wes – if someone is really in need, Wes The Clock Tower Wes will see about putting a food parcel together and deliver. -

Sutton Coldfield Four Oaks Childrens Centre Kittoe Road, Birmingham

Where to get Healthy Start Vitamins (Vitamin D Campaign) in the Birmingham Area Sutton Coldfield Four Oaks Childrens Centre Kittoe Road, Birmingham, B74 4RX 0121 323 1121 / New Hall Children Centre Langley Hall Drive, Birmingham, B75 7NQ 012107584233492 464 5170 Bush Babies Childrens Centre 1 Tudor Close, Sutton Coldfield, Birmingham, B73 6SX 0121 354 9230 James Preston Health Centre 61 Holland Road, Birmingham, B75 1RL 0121 465 5258 Boots Pharmacy 80-82 Boldmere Road, Birmingham, B73 5TJ 0121 354 2121 Stockland Green / Erdington Erdington Hall Childrens Centre Ryland Road, Birmingham, B24 8JJ 0121 464 3122 Featherstone' Chidren's Centre & Nusery School 29 Highcroft Road, Birmingham, B23 6AU 0121 675 3408 Lakeside Childrens Centre Lakes Road, Erdington, Birmingham, B23 7UH 0121 386 6150 Erdington Medical Centre 103 Wood End Road , Birmingham, B24 8NT 0121 373 0085 Dove Primary Care Centre 60 Dovedale Road, Birmingham, B23 5DD 0121 465 5715 Eaton Wood Medical Centre 1128 Tyburn Road, Birmingham, B24 0SY 0121 465 2820 Stockland Green Primary Care Centre 192 Reservoir Road, Birmingham, B23 6DJ 0121 465 2403 Boots Pharmacy 87 High Street, Erdington, Birmingham, B23 6SA 0121 373 0145 Boots Pharmacy Fort Shopping Park ,Unit 8, Birmingham, B24 9FP 0121 382 9868 Osborne Children's Centre Station Road, Erdington, Birmingham, B23 6UB 0121 675 1123 High Street Pharmacy 36 High Street, Birmingham, B23 6RH 0121 377 7274 Barney's Children Centre Spring Lane, Erdington, Birmingham, B24 6BY 0121 464 8397 Jhoots Pharmacy 70 Station Road, Bimringham, B23 -

NHS Birmingham and Solihull Clinical Commissioning Group Primary

NHS Birmingham and Solihull Clinical Commissioning Group Primary Care Networks April 2021 PCN Name ODS CODE Practice Name Name of Clinical GP Provider Alignment/ Director Federation Alliance of Sutton Practices M85033 The Manor Practice Dr Fraser Hewett Our Health Partnership PCN M85026 Ashfield Surgery M85175 The Hawthorns Surgery Balsall Heath, Sparkhill and M85766 Balsall Heath Health Centre – Dr Raghavan Dr Aman Mann SDS My Healthcare Moseley PCN M85128 Balsall Heath Health Centre – Dr Walji M85051 Firstcare Health Centre M85116 Fernley Medical Centre Y05826 The Hill General Practice M85713 Highgate Medical Centre M85174 St George's Surgery (Spark Medical Group) M85756 Springfield Medical Practice Birmingham East Central M85034 Omnia Practice Dr Peter Thebridge Independent PCN M85706 Druid Group M85061 Yardley Green Medical Centre M85113 Bucklands End Surgery M85013 Church Lane Surgery Bordesley East PCN Y02893 Iridium Medical Practice Dr Suleman Independent M85011 Swan Medical Practice M85008 Poolway Medical Centre M85694 Garretts Green M85770 The Sheldon Practice Bournville and Northfield M85047 Woodland Road Dr Barbara King Our Health Partnership PCN M85030 St Heliers M85071 Wychall Lane Surgery M85029 Granton Medical Centre NHS Birmingham and Solihull Clinical Commissioning Group Primary Care Networks April 2021 Caritas PCN M88006 Cape Hill Medical Centre Dr Murtaza Master Independent M88645 Hill Top Surgery (SWB CCG) M88647 Rood End Surgery (SWB CCG) Community Care Hall Green Y00159 Hall Green Health Dr Ajay Singal Independent -

Birmingham West Midlands

Stafford Stafford Stoke-on-Trent Stoke-on-Trent High Speed 2 planned route The North The North Rugeley Trent Valley Penkridge Rugeley Town birmingham Hednesford Cannock west midlands Landywood Bloxwich North London Derby Lichfield Trent Valley Northwestern The North East Leicester Railway Peterborough Bloxwich East Anglia Shrewsbury Lichfield City Mid Wales Virgin Trains Walsall Shenstone West Coast Blake Street Bescot Stadium Butlers Lane Hinckley Wolverhampton CrossCountry Tame Bridge Parkway Four Oaks under construction The Pipers Row Priestfield Crescent Loxdale Sutton Coldfield Wednesbury Parkway Hamstead Tamworth Wolverhampton The Bilston Bradley Wednesbury, Gt Western St St George’s Royal Coseley Central Lane Black Lake Wylde Green Polesworth West Midlands Dudley Street, Guns Village West Tipton Metro Dartmouth Street Perry Barr Chester Road Midlands Lodge Road Wilnecote Atherstone Railway Dudley Port West Bromwich Central Trinity Way Erdington London Sandwell & Kenrick Park Northwestern Dudley Handsworth Witton Gravelly Hill Nuneaton Railway The Winson Green Hawthorns Soho Aston CrossCountry Smethwick Jewellery Quarter Galton Bridge Langley Green St Paul’s Duddeston Virgin Trains St Chads Coleshill Parkway West Coast Rowley Regis Smethwick Bull Street Rolfe Street BIRMINGHAM Transport Old Hill Birmingham for Wales Cradley Heath Snow Hill BIRMINGHAM Town Grand Corporation Curzon Street Water Orton Bermuda Park Stourbridge Town Lye Hall Central Street Adderley Park Birmingham Centenary Square Stechford Interchange under Chiltern -

West Midlands Police Freedom of Information YEAR DISPOSAL

West Midlands Police Freedom of Information DRIVE WITHOUT DUE CARE AND ATTENTION BY LOCATION AND DISPOSAL METHOD FOR 2013-2017 YEAR DISPOSAL COMPLETION METHOD LOCATION STREET LOCATION LOCALITY LOCATION TOWN 2013 2013 Paid / Licence Endorsed M6 J7 Southbound WALSALL 2013 Cancelled Staion Road Stechford 2013 Retraining Course Attended And Completed SMALL HEATH BYPASS 2013 Cancelled M6 J 7 to 6 FOLESHILL ROAD, 2013 Retraining Course Attended And Completed COVENTRY 2013 Cancelled M6 SOUTH J 10A-10 2013 Retraining Course Attended And Completed Kitts Green Road 2013 Cancelled Haden Circus 2013 Cancelled TESSALL LANE NORTHFIELD BIRMINGHAM 2013 Cancelled STEELHOUSE LANE BIRMINGHAM 2013 Cancelled FOUR POUNDS AVENUE COVENTRY 2013 Retraining Course Attended And Completed Halesowen Street 2013 Cancelled CROSSFIELD ROAD BIRMINGHAM 2013 Cancelled M6 SOUTH J 10A-8 2013 Retraining Course Attended And Completed M6 NORTH J 5-6 2013 Cancelled BRISTOL ROAD BIRMINGHAM 2013 Retraining Course Attended And Completed M6 SOUTH J 7-6 2013 Cancelled DIGBETH HIGH STREET BIRMINGHAM 2013 Cancelled SMALL HEATH BYPASS BIRMINGHAM 2013 Retraining Course Attended And Completed HORSEFAIR 2013 Retraining Course Attended And Completed PHEONIX WAY COVENTRY 2013 Retraining Course Attended And Completed EDMONDS ROAD BIRMINGHAM 2013 Cancelled Metchley Park Road BIRMINGHAM 2013 Cancelled GARRISON CIRCUS 2013 Cancelled ANSTY ROAD COVENTRY 2013 Cancelled A453 COLLEGE ROAD KINGSTANDING 2013 Cancelled Suffolk Street 2013 Cancelled STONEY LANE SPARKBROOK 2013 Cancelled M6 NORTH 2013 -

Transport Delivery Committee

Transport Delivery Committee Date 14th September 2020 Report Title Bus Alliance Update Accountable Director Pete Bond, Director of Integrated Network Services Email: [email protected] Tel: 07824 547465 Accountable Edmund Salt, Network Development Manager employee(s) Email: [email protected] Tel: 07827 662197 Report Considered by Chair of Putting Passengers First Lead Members Recommendation(s) for action or decision: The Transport Delivery Committee is recommended: 1. To note the content of the report and current status of the West Midlands Bus Alliance. 2. To submit the report to the West Midlands Combined Authority Board for information. Purpose of Report 1. To report matters relating to the governance, operation, delivery and performance of the West Midlands Bus Alliance. West Midlands Bus Alliance Board Governance 2. Stuart Everton has been asked to re-join the Board to represent the Black Country Officers Group, replacing Amy Harhoff on the Board. 3. As a result of Covid-19 the West Midlands Bus Alliance Board has adapted to meeting virtually, three full Board meetings have taken place in May, June and July with the Board being kept updated on developments via weekly virtual meetings. 4. Bus Alliance Board member Graham Vidler and the CPT has been working extremely hard to ensure that bus services and operators have been given the priority they deserve in high level discussions with the DfT throughout the pandemic. A Bolder Bus Alliance 2020 5. At the Bus Alliance Board meeting on 5th February 2020, the Bus Alliance Board approved the ‘Bolder Bus Alliance’ aspirations and associated governance structure. -

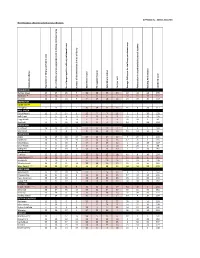

Libraries Ranked on Key Indicators C Ommun Ity Lib Ra Ry P O Pula Tio Nof Libr

APPENDIX 3a - NEEDS ANALYSIS Need Analysis: Libraries ranked on key indicators Community Library area catchment library of Population area catchment library in 0-19 people young and children of No. area catchment library in 65+ aged peope of No. Number of libraries within 2 miles of library issued items Total hours) (in usage PC Total visitors library visit per Cost area catchment the library for score IMD Average sessions educational and events in Participation Building Performance score Combined EDGBASTON Bartley Green 29 29 26 9 32 36 35 34 22 16 28 296 Harborne * 11 18 7 19 3 8 11 7 32 11 10 137 Quinton 14 14 10 9 7 19 18 12 25 19 20 167 ERDINGTON Castle Vale ** Erdington 2 4 5 1 10 10 12 21 16 8 28 117 HALL GREEN Balsall Heath 15 9 24 9 12 7 7 11 2 6 20 122 Hall Green 7 5 6 19 4 29 6 8 29 3 20 136 Kings Heath 5 6 4 19 2 11 2 3 28 10 1 91 Sparkhill 4 3 16 19 5 9 4 1 14 7 28 110 HODGE HILL Shard End 26 23 23 19 27 15 19 2 9 5 1 169 Ward End 1 1 8 1 8 12 15 13 11 12 10 92 LADYWOOD Aston 21 15 28 19 29 22 27 22 3 29 1 216 Birchfield 20 16 29 19 22 14 24 33 12 26 1 216 Bloomsbury 33 31 36 9 37 37 37 36 1 32 38 327 Small Heath 3 2 15 9 9 6 3 10 4 25 9 95 Spring Hill 34 34 34 19 31 13 23 29 7 27 10 261 NORTHFIELD Frankley 35 35 33 1 35 33 25 18 10 9 20 254 Kings Norton*** 18 20 14 1 15 28 17 5 24 18 1 161 Northfield 9 10 3 1 6 3 10 16 27 13 10 108 Weoley Castle 16 17 11 19 18 18 13 15 21 23 10 181 West Heath***** 30 32 27 0 24 17 28 20 26 34 38 276 PERRY BARR Handsworth 13 11 20 19 21 2 16 23 8 21 9 163 Kingstanding 24 21 19 9 23 25 21 -

Changing Places: Stories of Innovation and Tenacity in Five Birmingham Neighbourhoods

Changing places: stories of innovation and tenacity in five Birmingham neighbourhoods Research commissioned by The Pioneer Group March 2018 Foreword here has been a recent renaissance in Birmingham in working at a neighbourhood level – from localised service delivery, community asset transfer and co-production, Tthrough to neighbourhood planning and more recently community-led housing. Birmingham City Council have set out their locality policy to shape a “better deal for neighbourhoods”, with a committment to drive citizen governance, neighbourhood management, devolution deals and neighbourhood agreements. A neighbourhood summit was hosted by the Place Directorate of the City Council in December 2016. This explored how practitioners, agencies and residents can work more collaboratively to make our neighbourhoods and communities the best they can be. A number of themes emerged, around coordination of neighbourhood data, partnership working, a recognition that one size does not fit all, how best to join up services, build community capacity and resilience, and ensure a neighbourhood focus in city-wide strategies. Birmingham is home to excellent examples of community-based organisations and networks that have continued to exist, and thrive, despite the reduction of resources available to public services over the past seven years. Between 2005 and 2007 the Home Office funded the national FOREWORD Guide Neighbourhoods Programme to explore the effectiveness of resident-to-resident learning in promoting positive change in neighbourhoods. Three Birmingham neighbourhoods - Castle Vale, Balsall Heath and Witton Lodge - took part in the programme, and cascaded the learning within Birmingham. Taking the experience of the Guide Neighbourhoods, together Peter Richmond with the key themes that emerged from the neighbourhood Chief Executive, The Pioneer Group summit, we believe the time is right to establish a Birmingham- wide network of active neighbourhoods and communities. -

Liquid Transfer Devices

Europaisches Patentamt European Patent Office © Publication number: 0 590 695 A3 Office europeen des brevets EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION © Application number: 93119395.7 int. CIA B01L 3/00, G01N 33/52, G01 N 33/543 (§) Date of filing: 23.03.90 ® Priority: 23.03.89 GB 8906833 Balsall Heath, Birmingham B12 9HE(GB) 06.10.89 GB 8922513 Applicant: WALKER, Matthew Robert 51 Frederick Road @ Date of publication of application: Selly Oak, Birmingham B29 6NX(GB) 06.04.94 Bulletin 94/14 @ Inventor: Bunce, Roger Abraham ® Publication number of the earlier application in 117 Berberry Close, accordance with Art.76 EPC: 0 417 243 Bournville Birmingham B30 1TB(GB) © Designated Contracting States: Inventor: THORME, Gary Harold Gregory AT BE CH DE DK ES FR GB IT LI LU NL SE Henry 84 Newcombe Road ® Date of deferred publication of the search report: Handsworth, Birmingham B21 8BX(GB) 13.07.94 Bulletin 94/28 Inventor: Gibbons, John Edwin Charles 40 St. Peters Close Hall Green, Birmingham B28 OEF(GB) @ Applicant: Bunce, Roger Abraham Inventor: KEEN, Louise Jane 117 Berberry Close, 30 Alpha Close Bournville Balsall Heath, Birmingham B12 9HE(GB) Birmingham B30 1TB(GB) Inventor: WALKER, Matthew Robert Applicant: THORME, Gary Harold Gregory 51 Frederick Road Henry Selly Oak, Birmingham B29 6NX(GB) 84 Newcombe Road Handsworth, Birmingham B21 8BX(GB) Applicant: Gibbons, John Edwin Charles 0 Representative: Parker, Geoffrey 40 St. Peters Close Patents Department Hall Green, Birmingham B28 OEF(GB) British Technology Group Ltd Applicant: KEEN, Louise Jane 101 Newington Causeway 30 Alpha Close London SE1 6BU (GB) © Liquid transfer devices.