Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Storie Milanesi Www

Storie Milanesi WWW. STORIEMILANESI.ORG Franco Albini A Milano il ’68 arrivò cinque anni prima, Franco. Era il gennaio del ’63 quando un gruppo di studen- ti della facoltà di architettura avanzarono delle richieste di riorganizzazione dei corsi. Non furono ascoltati. A febbraio iniziò lo sciopero. Erano ragazzi, chiedevano di uscire dai lacci soffocanti dell’ac- cademia, di non seguire più i dettami reazionari di chi ancora costruiva come se la guerra non avesse mai avuto luogo, come se il boom economico non fosse esploso. A Milano solo Ernesto Nathan Rogers riusciva ad emozionarli. Certamente non Cassi Ramelli e la sua neorinascimentale sede della SNIA Vi- scosa in corso di Porta Nuova. Si chiamavano Cortese, Farè, Stevan, c’era quel ragazzo di Genova, che di giorno studiava e poi veniva a lavorare nel tuo studio, c’era tuo figlio Marco... Era la meglio gioventù di quegli anni. Volevano vivere il loro tempo, sentire le voci di chi l’architettura la faceva per davvero. Volevano te, Franco. Tu che studiasti al Politecnico negli stessi anni di Terragni, che girasti per l’Europa per conoscere Mies van der Rohe o Le Corbusier, che a Casabella legasti con Edoardo Persico, che con Giuseppe Pagano e Ignazio Gardella immaginaste il piano urbanistico per una “Milano Verde” cercando l’ordine razionale contro il disordine delle città storiche. Eravate giovani e integralisti, volevate dare ai nuovi cittadini inur- bati case essenziali, salubri, dignitose, volevate donare alla città il volto del secolo che stavate vivendo. Eri di Robbiate, venivi dalla Brianza, Franco. Tuo padre Baldassare era un ingegnere che aveva investito nel baco da seta prima che la crisi del ’29 spazzasse via tutto. -

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE Women Contribution through the Pages of “Domus” (1946-1968): Architecture and Urban Planning in the Italian Panorama Original Women Contribution through the Pages of “Domus” (1946-1968): Architecture and Urban Planning in the Italian Panorama / GARDA, EMILIA MARIA; SERRA, CHIARA; STELLA, ANNALISA. - STAMPA. - (2016), pp. 31-37. ((Intervento presentato al convegno MoMoWo 2nd International Conference-Workshop tenutosi a Ljubljana nel 3-4-5- October 2016. Availability: This version is available at: 11583/2653569 since: 2020-01-31T12:40:47Z Publisher: ZRC SAZU, France Stele Institute of Art History Published DOI: Terms of use: openAccess This article is made available under terms and conditions as specified in the corresponding bibliographic description in the repository Publisher copyright default_conf_editorial [DA NON USARE] - (Article begins on next page) 02 October 2021 Proceedings of the 2nd MoMoWo International Conference- Workshop Research Centre of Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, France Stele Institute of Art History, 3–5 October 2016, Ljubljana Ljubljana 2018 Proceedings of the 2nd MoMoWo International Conference-Workshop Research Centre of Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, France Stele Institute of Art History, 3–5 October 2016, Ljubljana Collected by Helena Seražin, Caterina Franchini and Emilia Garda MoMoWo Scientific Committee: POLITO (Turin/Italy) Emilia GARDA, Caterina FRANCHINI IADE-U (Lisbon/Portugal) Maria Helena SOUTO UNIOVI (Oviedo/Spain) Ana María FERNÁNDEZ -

Main Architectural Works of Franco Albini 1931 - 1945 Work Description Period

Main architectural works of Franco Albini 1931 - 1945 Work Description Period Steel frame house, V Triennial of Milan s(with Renato Camus, Giulio Albini's first experience working under Pagano's direction occurred in 1933 while collaborating with 1933 Minoletti, Giuseppe Mazzoleni, Giuseppe Pagano, Giancarlo Palanti) Pagano's group (Renato Camus, Giulio Minoletti, Giuseppe Mazzoleni, and Giancarlo Palanti) on the design of the Steel Frame House erected in Parco Sempione during the V Trien¬nale. Formally , the uninspired design of the Steel Frame House was probably due to Pagano's overriding preoccupation with the practical application of standardized building materials. The repetitive nature of the structural bays and Windows of the Steel Frame House were symbols of economically correct, serially produced, industriai standards. For the VI Triennale in 1936 Albini and his partners, Renato Camus and Giancarlo Palanti, collaborated with Paolo Clausetti, Ig¬nazio Gar della, Giovanni Mazzoleni, Giulio Minoletti, Gabriele Mucchi, and Giovanni Romano on the design for the Exhibit on Hous-ing, installed in the new pavilion designed by Pagano in Parco Sempione. Consistent with Pagano's interpretation of functionalism, the group designed both built-in furnishings and individuai pieces constructed with ordinary materials capable of being produced in quan-tity. The intention of Pagano and Albini's group was to convince the public that mass- produced objects could be designed with care, economy, and quality. Main architectural works of Franco Albini | 3 Work Description Period The Hall of Aerodynamics, Aeronauitc Exposition, Milan (The exhibit) must be considered as a complete whole, an experiment of collective work. The criterion of 1934 the system and the particular solutions are equal in ali the rooms, and connected to each other not only by a stylistic unity, but also by that ideal process that establishes an uninterrupted continuiti between the principle and the cause. -

ARCHITETTURA in ITALIA 1910 - 1980 Una Collezione Di Centodieci Libri E Documenti Originali

ARCHITETTURA IN ITALIA 1910 - 1980 Una collezione di centodieci libri e documenti originali L’ARENGARIO STUDIO BIBLIOGRAFICO Edizioni dell’Arengario Gussago Franciacorta 2017 ARCHITETTURA IN ITALIA 1910 - 1980 Una collezione di settandue libri e documenti originali a cura di Bruno Tonini, con un testo di Giovanni Michelucci L’ARENGARIO STUDIO BIBLIOGRAFICO “Io penso e credo in un tempo, vicino o lontano, in cui, come nelle antiche civiltà, tutto ciò che servirà alla vita sarà «vero», nato cioè spontaneamente con com- piuta conoscenza delle possibilità pratiche, economiche, tecniche e con piena convinzione che la struttura non si deve nascondere o mascherare ma svelare nella forma e che il «gusto» si modella sulla forma che nasce con l’urgenza e l’e- videnza di un fatto vitale. Allora le case, gli edifici pubblici, la forchetta, il ferro da stiro testimonieranno della unità d’intendimenti di un popolo, di affermare senza equivoco la propria realtà e la fiducia nella validità del proprio tempo: ogni oggetto troverà la sua forma nella collaborazione di una collettività, dove le qualità native diversissime di ciascuno potranno essere pienamente valorizzate e potenziate. Io non sono dunque libero dalle malìe della forma. Se ho insistito sul fattore eco- nomico è perché sono convinto che l’architettura non è nella varietà dei temi ma nella organizzazione di un’opera architettonica... Non credo tanto nella «im- maginazione» quanto invece nella «fantasia», che non sconfina mai nell’arbitrio, ma si vale appunto dei mezzi usuali e li dosa così, da ottenere variazioni infinite su pochi temi che esigenze economiche, sociali, tecniche hanno generalizzato.” Giovanni Michelucci [Giovanni Michelucci, Felicità dell’architetto, Firenze, Editrice Il Libro, 1949, pp. -

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE Proceedings of the 2nd MoMoWo International Conference-Workshop.Research Centre of Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, France Stele Institute of Art History, 3–5 October Original Proceedings of the 2nd MoMoWo International Conference-Workshop.Research Centre of Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, France Stele Institute of Art History, 3–5 October 2016, Ljubljana / Franchini, Caterina; Garda, EMILIA MARIA; Seražin, Helena. - ELETTRONICO. - (2018), pp. 1-259. Availability: This version is available at: 11583/2746292 since: 2020-01-31T10:11:46Z Publisher: ZRC SAZU, France Stele Institute of Art History, Založba ZRC Published DOI: Terms of use: openAccess This article is made available under terms and conditions as specified in the corresponding bibliographic description in the repository Publisher copyright (Article begins on next page) 04 August 2020 Proceedings of the 2nd MoMoWo International Conference- Workshop Research Centre of Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, France Stele Institute of Art History, 3–5 October 2016, Ljubljana Ljubljana 2018 Proceedings of the 2nd MoMoWo International Conference-Workshop Research Centre of Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, France Stele Institute of Art History, 3–5 October 2016, Ljubljana Collected by Helena Seražin, Caterina Franchini and Emilia Garda MoMoWo Scientific Committee: POLITO (Turin/Italy) Emilia GARDA, Caterina FRANCHINI IADE-U (Lisbon/Portugal) Maria Helena SOUTO UNIOVI (Oviedo/Spain) Ana María FERNÁNDEZ GARCÍA VU (Amsterdam/Netherlands) -

Tacchini-Design-Classics.Pdf

Design Classics 1939 2018 Design Classics 01 Tacchini Re–Editions Design Classics “If you are not curious, Maestri or “masters” are those charismatic figures capable of teaching and handing down an art through their direct forget it.” actions and also through the inheritance of their actual works. In design the maestri communicate through the classics, timeless designs far from any idea of fashions and trends yet so powerful as to produce a style naturally. Tacchini has set aside some rooms in its living environment for the classics and the masters who have designed them, in a process of revivals which are a challenge and a lesson on contemporary style. Achille e Pier Giacomo Castiglioni The Castiglioni studio was established in 1938 by brothers Livio and Pier Giacomo, while for certain projects, Luigi Caccia Dominioni also worked alongside them. In 1944 Achille joined the studio: the partnership between the three brothers continued until 1952, when Livio set up on his own, while continuing to work with Pier Giacomo and Achille for some special projects. Achille and Pier Giacomo worked together without any clear division of roles, but with equal participation, and constant discussion and exchange of ideas. 1. Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni 2. Babela (1958), re-edition by Tacchini, 2010 1 Achille Castiglioni 2 Design Classics 02 Tacchini Re–Editions 03 Babela, designed by Achille + Pier Giacomo Castiglioni, 1958 Babela Designed by Achille + Pier Giacomo Castiglioni, 1958. Re-Edition by Tacchini, 2010. Category: Chair. On left page with Nastro (Table) by Pietro Arosio. Design Classics 04 Babela 05 Babela Designed by Achille Castiglioni, 1982. -

Stefano Della Torre Massimiliano Bocciarelli Laura Daglio Raffaella

Research for Development Stefano Della Torre Massimiliano Bocciarelli Laura Daglio Raffaella Neri Editors Buildings for Education A Multidisciplinary Overview of The Design of School Buildings Research for Development Series Editors Emilio Bartezzaghi, Milan, Italy Giampio Bracchi, Milan, Italy Adalberto Del Bo, Politecnico di Milano, Milan, Italy Ferran Sagarra Trias, Department of Urbanism and Regional Planning, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain Francesco Stellacci, Supramolecular NanoMaterials and Interfaces Laboratory (SuNMiL), Institute of Materials, Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Lausanne, Vaud, Switzerland Enrico Zio, Politecnico di Milano, Milan, Italy; Ecole Centrale Paris, Paris, France The series Research for Development serves as a vehicle for the presentation and dissemination of complex research and multidisciplinary projects. The published work is dedicated to fostering a high degree of innovation and to the sophisticated demonstration of new techniques or methods. The aim of the Research for Development series is to promote well-balanced sustainable growth. This might take the form of measurable social and economic outcomes, in addition to environmental benefits, or improved efficiency in the use of resources; it might also involve an original mix of intervention schemes. Research for Development focuses on the following topics and disciplines: Urban regeneration and infrastructure, Info-mobility, transport, and logistics, Environment and the land, Cultural heritage and landscape, Energy, Innovation in processes and technologies, Applications of chemistry, materials, and nanotech- nologies, Material science and biotechnology solutions, Physics results and related applications and aerospace, Ongoing training and continuing education. Fondazione Politecnico di Milano collaborates as a special co-partner in this series by suggesting themes and evaluating proposals for new volumes. -

838 VELIERO Family ALBINI Catalogue I Maestri Year of Design 1940 Year of Production 2011 / 2019

838 VELIERO Family ALBINI Catalogue I Maestri Year of design 1940 Year of production 2011 / 2019 Defying the laws of physics, going beyond what we normally understand by the conditions of equilibrium, this bookcase is nothing short of a manifesto for Cassina’s design and construction capabilities. After a lengthy period of research and development, ably assisted by state-of-the-art technology, the company’s designers created a production prototype of the original 1940 piece that architect Franco Albini made as a one-off for his Milan home. Respecting the authentic underlying concept of the design, with its compelling experimental feel, as well as its surprisingly spare, linear looks, today’s model preserves the minimal ideal of the original: a feeling of air and light so that the books and objets seem to float free. Thus does Cassina restore to the contemporary world of design one of its most emblematic artefacts, a piece that has acquired the status of a work of art, as magical now as it was when it was first seen. It is now also available in an exclusive limited edition in ashwood stained black with stainless steel metallic caps and elements. Gallery Dimensions Designer He was a major figure in the Rationalist Movement, excelling in architectural, furniture, industrial and museum design. After receiving a degree in architecture from the Politecnico di Milano in 1929, he worked with the Ponti and Lancia design studios. His work for the magazine Casabella also played a key part in his development, marking his conversion to the Rationalist Movement and his becoming its spokesman on the Italian cultural scene. -

From Architecture to Design and Back

Res Mobilis Revista internacional de investigación en mobiliario y objetos decorativos Vol. 9, nº. 10, 2020 FROM ARCHITECTURE TO DESIGN AND BACK: THE ARCHITECTURAL ROOTS OF THE ITALIAN DESIGN SYSTEM, 1920-1980 DE LA ARQUITECTURA AL DISEÑO IDA Y VUELTA: LAS RAÍCES ARQUITECTÓNICAS DEL SISTEMA DE DISEÑO ITALIANO, 1920-1980 Elena Dellapiana* Politecnico di Torino Fiorella Bulegato Università IUAV di Venezia Abstract The histories of Italian design and architecture may be more readily understood if one considers that many of the protagonists are architect-designers. Identifying the root of this convergence in an academic and professional educational system based on the idea of the "complete architect", trained to work at any scale of design, this paper frames the work of the architect-designers within the cultural, economic and manufacturing context of the period between the 1920s and 1980s, when for historical reasons their role became particularly significant. Furthermore, many design historians in Italy are the product of the same education as the architects, and having followed the same course of studies as the architectural historians, they acquired the same techniques of investigation and interpretation, which they later refined in their own fields. The theme is thus explored from the perspectives of the two authors, both architects but with specific training one as an architectural historian, and the other as a design historian. The relationship between the two research directions – the theoretical debate and its narrations, the relationship between designers and manufacturers – makes it possible to clarify some of the aspects that distinguish the history of Italian design culture compared to that of other Western nations. -

ATINER's Conference Paper Series ARC2013-0755

ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: ARC2013-0755 Athens Institute for Education and Research ATINER ATINER's Conference Paper Series ARC2013-0755 Ancient Material and Steel: Project Strategies on the Content and the Container of the Museums in the Period of the Italian Reconstruction Laura Ciammitti PhD student Department of Civil Building Architecture and Environmental Engineering University of L’Aquila Italy 1 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: ARC2013-0755 Athens Institute for Education and Research 8 Valaoritou Street, Kolonaki, 10671 Athens, Greece Tel: + 30 210 3634210 Fax: + 30 210 3634209 Email: [email protected] URL: www.atiner.gr URL Conference Papers Series: www.atiner.gr/papers.htm Printed in Athens, Greece by the Athens Institute for Education and Research. All rights reserved. Reproduction is allowed for non-commercial purposes if the source is fully acknowledged. ISSN 2241-2891 13/12/2013 2 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: ARC2013-0755 An Introduction to ATINER's Conference Paper Series ATINER started to publish this conference papers series in 2012. It includes only the papers submitted for publication after they were presented at one of the conferences organized by our Institute every year. The papers published in the series have not been refereed and are published as they were submitted by the author. The series serves two purposes. First, we want to disseminate the information as fast as possible. Second, by doing so, the authors can receive comments useful to revise their papers before they are considered for publication in one of ATINER's books, following our standard procedures of a blind review. Dr. -

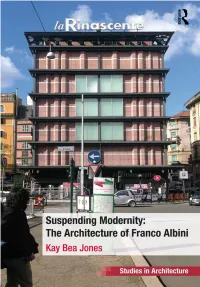

THE ARCHITECTURE of FRANCO ALBINI Ashgate Studies in Architecture Series

SUSPENDING MODERNITY: THE ARCHITECTURE OF FRANCO ALBINI Ashgate Studies in Architecture Series SERIES EDITOR: EAMONN CANNIFFE, MANCHESTER SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE, MANCHESTER METROPOLITAN UNIVERSITY, UK The discipline of Architecture is undergoing subtle transformation as design awareness permeates our visually dominated culture. Technological change, the search for sustainability and debates around the value of place and meaning of the architectural gesture are aspects which will affect the cities we inhabit. This series seeks to address such topics, both theoretically and in practice, through the publication of high quality original research, written and visual. Other titles in this series Shoah Presence: Architectural Representations of the Holocaust Eran Neuman ISBN 978 1 4094 2923 4 Reconstructing Italy The Ina-Casa Neighborhoods of the Postwar Era Stephanie Zeier Pilat ISBN 978 1 4094 6580 5 The Architecture of Edwin Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew Twentieth Century Architecture, Pioneer Modernism and the Tropics Iain Jackson and Jessica Holland ISBN 978 1 4094 5198 3 Recto Verso: Redefining the Sketchbook Edited by Angela Bartram, Nader El-Bizri and Douglas Gittens ISBN 978 1 4094 6866 0 The Architecture of Luxury Annette Condello ISBN 978 1 4094 3321 7 Building the Modern Church Roman Catholic Church Architecture in Britain, 1955 to 1975 Robert Proctor ISBN 978 1 4094 4915 7 The Architectural Capriccio Memory, Fantasy and Invention Edited by Lucien Steil ISBN 978 1 4094 3191 6 Suspending Modernity: The Architecture of Franco Albini Kay Bea Jones School of Architecture, Ohio State University, USA ROUTLEDGE Routledge Taylor & Francis Group LONDON AND NEW YORK First published 2014 by Ashgate Publishing Published 2016 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Copyright © Kay Bea Jones 2014 Kay Bea Jones has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identied as the author of this work. -

Redalyc.¡Circulen! El Lenguaje De La Arquitectura En Circulación Y Como

ARQ ISSN: 0716-0852 [email protected] Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile Chile Galán, Ignacio G. ¡Circulen! El lenguaje de la arquitectura en circulación y como instrumento para la circulación ARQ, núm. 96, agosto, 2017, pp. 134-149 Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile Santiago, Chile Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=37552672014 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative GALÁN Palabras clave Metro Infraestructura Albini Tafuri Milán Keywords Subway Infrastructure Albini CirCulate! Tafuri Milano Architecture’s language in circulation and as an instrument for circulation1 FIG 1 Carlo Orsi. Although architecture seems to have Metropolitana Milanese. Milán / Milano, 1964. a minor role in the definition of urban © Carlo Orsi infrastructures, softening its roughness and aiding its functionality, the following contribution argues it can do more than that. The project for the Milano subway by Albini and Helg shows that architecture and design can also ground the role of infastructures as instruments of cultural coordination and social 134 articulation in the post-Fordist city. iGnACiO G. GA lán Term Assistant Professor Barnard+Columbia Colleges, New York, USA UC CHILE — ARQ 96 onsider the following image to begin: a C policeman (or perhaps a policewoman?), posing in a relaxed position (Fig. 1). She is framed horizontally by a continuous banner announcing a subway station –Duomo – and the edge of a platform, positioned at the top and the bottom of the photograph.